Suppression of the Society of Jesus facts for kids

The suppression of the Society of Jesus was a time when the Jesuits, a group of Catholic priests and brothers, were removed from many countries in Western Europe and their colonies. This started in 1759 and led to the Pope officially ending their order in 1773.

The Jesuits were kicked out of the Portuguese Empire (1759), France (1764), the Two Sicilies, Malta, Parma, the Spanish Empire (1767), and Austria and Hungary (1782). This happened because of political reasons in each country and in Rome. The Pope, Pope Clement XIV, sadly agreed to these demands from Catholic kingdoms, even though there wasn't a strong religious reason for it.

Historians believe several things caused this. The Jesuits were sometimes involved in politics, which made people distrust them. They were also seen as too close to the Pope and his power, which worried leaders who wanted more control over their own countries. In France, many different groups, including those who wanted new ways of thinking, were tired of the old system. Kings who wanted to make their power stronger and separate government from church saw the Jesuits as too independent and too loyal to the Pope.

Even though Pope Clement XIV officially ended the Society with a special letter called Dominus ac Redemptor on July 21, 1773, the Jesuits didn't completely disappear. They continued their work secretly in places like China, Russia, Prussia, and the United States. In Russia, Catherine the Great even allowed them to start a new training center for new members. Later, in 1814, another Pope, Pope Pius VII, brought the Society of Jesus back to life, and the Jesuits began their work again in many countries.

Contents

- Why the Jesuits Were Suppressed

- How the Suppression Started

- The Pope Officially Suppresses the Jesuits in 1773

- Jesuits Are Restored

- Images for kids

- See also

Why the Jesuits Were Suppressed

Before the 1700s, the Jesuits had been banned in some places, like parts of the Venetian Republic, because of disagreements between the Republic and the Pope.

By the mid-1700s, the Jesuits were known in Europe for being good at politics and making money. Kings in many European countries became more and more worried about what they saw as too much influence from a foreign group. Kicking the Jesuits out of their countries also meant that governments could take their wealth and possessions. However, historians are not sure how much this desire for wealth was a main reason for the expulsions.

Different countries used various events as reasons to act against the Jesuits. Political fights between kings, especially in France and Portugal, started with land disputes in 1750. These fights eventually led to countries cutting off ties with Rome and the Pope dissolving the Society in most of Europe. Some Jesuits were even executed. The Portuguese Empire, France, the Two Sicilies, Parma, and the Spanish Empire were all involved.

The problems began with trade arguments in Portugal in 1750, in France in 1755, and in the Two Sicilies in the late 1750s. In 1758, the government of Joseph I of Portugal took advantage of the aging Pope Benedict XIV. They sent Jesuits away from South America after moving them and their native workers, and then fought a short war. Portugal officially ended the Jesuit order in 1759. In 1762, the French Parliament (a court, not a law-making body) ruled against the Society in a large money problem, pressured by many groups, both from inside the Church and from powerful people outside, like Madame de Pompadour, the king's mistress. Austria and the Two Sicilies ended the order by official command in 1767.

How the Suppression Started

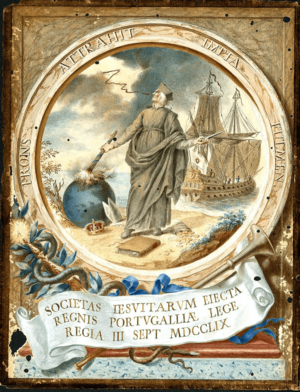

Portugal and Its Empire: The First Suppression in 1759

There were long-standing disagreements between the Portuguese king and the Jesuits. These problems grew when the Count of Oeiras (who later became the Marquis of Pombal) became the king's main minister. This led to the Jesuits being expelled in 1759. The Távora affair in 1758, an attempt on the king's life, was used as a reason for the expulsion and for the crown to take Jesuit property. Historians say that the Jesuits' independence, power, wealth, control of education, and ties to Rome made them easy targets for Pombal, who wanted the king to have all the power.

Portugal's argument with the Jesuits started over a land exchange in South America with Spain. In a secret treaty in 1750, Portugal gave Spain the disputed Colonia del Sacramento in exchange for the Seven Reductions of Paraguay. These were independent Jesuit missions that were technically Spanish land. The native Guaraní, who lived in these missions, were told to leave their homes. The Guaraní fought back against this move, leading to the Guaraní War. This war was a disaster for the Guaraní. In Portugal, the conflict grew, with many writings criticizing or defending the Jesuits. For over a century, the Jesuits had protected the Guaraní from being enslaved through their mission villages, as shown in the movie The Mission. The Portuguese colonists then pushed for the Jesuits to be expelled.

On April 1, 1758, Pombal convinced the old Pope Benedict XIV to have a Portuguese cardinal, Cardinal Saldanha, investigate the Jesuits. The Pope was doubtful about how serious the problems were. He ordered a careful investigation, but said that any serious issues should be reported back to him. Pope Benedict died the next month, on May 3. On May 15, Saldanha, who had only received the Pope's order two weeks before, announced that the Jesuits were guilty of "illegal, public, and scandalous business" in Portugal and its colonies. He had not visited the Jesuit houses as ordered and made decisions on matters the Pope had kept for himself.

Pombal also connected the Jesuits to the Távora affair, an attempt to kill the king on September 3, 1758. He claimed this was because the Jesuits were friends with some of the suspected plotters. On January 19, 1759, Pombal issued a rule taking over all Jesuit property in Portuguese lands. The next September, he sent about a thousand Portuguese Jesuit priests to the Pontifical States (lands ruled by the Pope), keeping foreign Jesuits in prison. Among those arrested and executed was Gabriel Malagrida, a Jesuit priest, for "crimes against the faith." After Malagrida's execution in 1759, the Portuguese king officially ended the Society. The Portuguese ambassador was called back from Rome, and the Pope's representative was expelled. Portugal and Rome did not have diplomatic relations again until 1770.

France Suppresses the Jesuits in 1764

The suppression of the Jesuits in France started in the French island colony of Martinique. There, the Society of Jesus owned sugar plantations worked by enslaved people and free laborers. Their large mission plantations had many local people working under the usual tough conditions of colonial farming in the 1700s. The Catholic Encyclopedia in 1908 said that missionaries selling goods (which was unusual for a religious order) was allowed partly to pay for mission costs and partly to protect the native people from dishonest traders.

Father Antoine La Vallette, who was in charge of the Martinique missions, borrowed money to expand the colony's undeveloped resources. But when the Seven Years' War with England began, ships carrying goods worth about 2 million livres were captured. La Vallette suddenly went bankrupt for a large amount of money. His lenders asked the Jesuit leader in Paris for payment. But he said he was not responsible for the debts of an independent mission, though he offered to try to find a solution. The lenders went to court and won in 1760. The court ordered the Society to pay and allowed them to take Jesuit property if they didn't. On their lawyers' advice, the Jesuits appealed to the Parlement of Paris. This turned out to be a bad move for them. The Parlement not only supported the lower court on May 8, 1761, but once they had the case, the Jesuits' enemies in that assembly decided to attack the Order.

The Jesuits had many opponents. The Jansenists, a group within the Church, were among their enemies. The Sorbonne, a rival school, joined with those who supported the French king's power over the Pope, the Philosophes (thinkers of the Enlightenment), and the writers of the Encyclopédie. King Louis XV was not a strong leader. His wife and children supported the Jesuits. His clever first minister, the Duc de Choiseul, worked with the Parlement and the royal mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Madame de Pompadour was a strong opponent because the Jesuits had refused to forgive her sins since she was living with the King of France outside of marriage. The Parlement of Paris eventually overcame all opposition.

The attack on the Jesuits began on April 17, 1762, by Abbé Chauvelin, who was sympathetic to the Jansenists. He criticized the rules of the Society of Jesus, which were then publicly looked at and discussed in a hostile way by the press. The Parlement published its Extraits des assertions, a collection of writings from Jesuit thinkers and church lawyers. These writings were used to claim that the Jesuits taught all kinds of bad morals and errors. On August 6, 1762, the final decision was proposed to the Parlement by the Advocate General Joly de Fleury, calling for the Society to be ended. But the king stepped in, causing an eight-month delay. During this time, a compromise was suggested. If the French Jesuits separated from the main Society led by the Jesuit General (who was directly under the Pope) and came under a French leader, following French customs like the French Church, the king would still protect them. The French Jesuits refused this idea. On April 1, 1763, their schools were closed. By another order on March 9, 1764, the Jesuits were told to give up their vows or be banished. At the end of November 1764, the king signed an order dissolving the Society throughout his lands. Some local parliaments still protected them, like in Franche-Comté, Alsace, and Artois. In the draft of the order, the king removed many parts that suggested the Society was guilty. He wrote to Choiseul, "If I follow the advice of others for the peace of my kingdom, you must make the changes I suggest, or I will do nothing. I say no more, lest I should say too much."

Jesuits Decline in New France

After the British won against the French in Quebec in 1759, France lost its North American land called New France. Jesuit missionaries had been very active there among the native peoples in the 1600s. British rule affected the Jesuits in New France, but their numbers and locations were already decreasing. By 1700, the Jesuits had decided to only keep their existing posts instead of trying to start new ones beyond Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa. Once New France was under British control, the British stopped any more Jesuits from coming in. By 1763, only twenty-one Jesuits were still in what was now the British colony of Quebec. By 1773, only eleven Jesuits remained. The British king claimed Jesuit property in Canada that same year and declared that the Society of Jesus in New France was dissolved.

Spain Expels the Jesuits in 1767

Why Spain Expelled the Jesuits

The expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain and its colonies, and from its dependent Kingdom of Naples, was the last of these expulsions. Portugal (1759) and France (1764) had already done it. The Spanish king had already started making many changes in his overseas empire, like reorganizing how areas were governed, changing economic rules, and building a military. So, the expulsion of the Jesuits is seen as part of these general changes, known as the Bourbon Reforms. These reforms aimed to reduce the growing independence of Spanish people born in America, to bring back control to the king, and to increase money for the crown. Some historians doubt that the Jesuits were actually plotting against the Spanish king, which was the immediate reason given for their expulsion.

People in Spain at the time blamed the expulsion of the Jesuits on the Esquilache Riots. These riots were named after an Italian advisor to the Bourbon king Carlos III. The riots started after a law was passed that limited how men could dress, such as wearing large capes and wide hats. This law was seen as an "insult to Spanish pride."

King Carlos fled to the countryside when an angry crowd of protesters gathered at the royal palace. The crowd shouted, "Long Live Spain! Death to Esquilache!" His palace guards fired warning shots over their heads. One story says that a group of Jesuit priests appeared, calmed the protesters with speeches, and sent them home. Carlos decided to cancel the new tax and the hat rule and fire his finance minister.

The king and his advisors were worried by the uprising, which challenged the king's power. The Jesuits were accused of encouraging the crowd and publicly accusing the king of religious crimes. Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, a lawyer for the Council of Castile (which oversaw central Spain), wrote a report that the king read. Charles III ordered a special royal group to create a plan to expel the Jesuits. This group first met in January 1767. They based their plan on how France's Philip IV acted against the Knights Templar in 1307, focusing on surprising them. Charles's advisor Campomanes had written about the Templars in 1747, which might have influenced how the Jesuit suppression was carried out. One historian says, "Charles III would never have dared to expel the Jesuits if he had not been sure of support from an important group within the Spanish Church." Jansenists and other religious orders had long been against the Jesuits and wanted to reduce their power.

The Secret Plan to Expel the Jesuits

King Charles's ministers kept their discussions secret, as did the king. He said he was acting for "urgent, just, and necessary reasons, which I keep in my royal mind." The letters of Bernardo Tanucci, Charles's minister in Naples who was against church power, show the ideas that guided Spanish policy. Charles ran his government through the Count of Aranda, who read Voltaire, and other liberal thinkers.

The group met on January 29, 1767, and planned the expulsion of the Jesuits. Secret orders, to be opened at sunrise on April 2, were sent to all regional governors and military commanders in Spain. Each sealed envelope had two documents. One was a copy of the order expelling "all members of the Society of Jesus" from Charles's Spanish lands and taking all their property. The other told local officials to surround Jesuit schools and homes on the night of April 2, arrest the Jesuits, and arrange for them to be taken to ships waiting at various ports. King Carlos's last sentence read: "If a single Jesuit, even if sick or dying, is still to be found in the area under your command after the embarkation, prepare yourself to face summary execution" (meaning immediate death).

Pope Clement XIII, who received a similar demand from the Spanish ambassador to the Vatican a few days before the order would take effect, asked King Charles, "by what authority?" and warned him of eternal punishment. Pope Clement could not stop it, and the expulsion happened as planned.

Jesuits Expelled from Mexico (New Spain)

In New Spain (Mexico), the Jesuits had actively taught Christianity to native peoples on the northern border. But their main work was educating wealthy criollo (Spanish people born in America) men, many of whom became Jesuits themselves. Of the 678 Jesuits expelled from Mexico, 75% were born in Mexico. In late June 1767, Spanish soldiers removed the Jesuits from their 16 missions and 32 stations in Mexico. No Jesuit could be excused from the king's order, no matter how old or sick. Many died on the difficult journey along the cactus-filled trail to the Gulf Coast port of Veracruz, where ships waited to take them to exile in Italy.

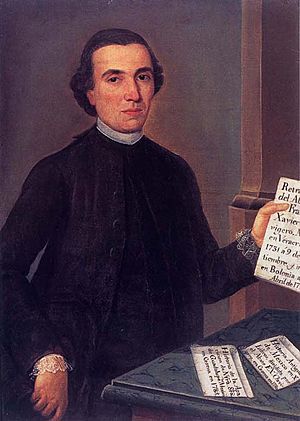

There were protests in Mexico about so many Jesuit members of important families being exiled. But the Jesuits themselves obeyed the order. Since the Jesuits owned large land estates in Mexico—which supported their work with native peoples and their education of criollo elites—these properties became a source of wealth for the king. The king sold them off, which helped the treasury. The criollo buyers gained productive and well-run properties. Many criollo families were angry at the king's actions, seeing it as a "tyrannical act." One famous Mexican Jesuit, Francisco Javier Clavijero, wrote an important history of Mexico during his exile in Italy, focusing on the native peoples. Alexander von Humboldt, a famous German scientist who spent a year in Mexico in 1803–04, praised Clavijero's work on the history of Mexico's native peoples.

Because the Spanish missions on the Baja California peninsula were so isolated, the expulsion order did not arrive there in June 1767, as it did in the rest of New Spain. It was delayed until the new governor, Gaspar de Portolá, arrived with the news and order on November 30. By February 3, 1768, Portolá's soldiers had removed the peninsula's 16 Jesuit missionaries from their posts and gathered them in Loreto. From there, they sailed to the Mexican mainland and then to Europe. Portolá showed sympathy for the Jesuits and treated them kindly, even as he ended their 70 years of mission-building in Baja California. The Jesuit missions in Baja California were given to the Franciscans and later to the Dominicans. The future missions in Alta California were started by Franciscans.

The change in the Spanish colonies in the New World was especially big, as missions often controlled the distant settlements. Almost overnight, in the mission towns of Sonora and Arizona, the "black robes" (Jesuits) disappeared, and the "gray robes" (Franciscans) took their place.

Expulsion from the Philippines

The royal order expelling the Society of Jesus from Spain and its lands reached Manila on May 17, 1768. Between 1769 and 1771, the Jesuits were transported from the Spanish East Indies to Spain and then sent to Italy.

Spanish Jesuits Sent to Italy

Spanish soldiers rounded up the Jesuits in Mexico, marched them to the coasts, and put them below the decks of Spanish warships heading for the Italian port of Civitavecchia in the Papal States (lands ruled by the Pope). When they arrived, Pope Clement XIII refused to let the ships unload their prisoners onto papal land. Fired upon by cannons from the shore of Civitavecchia, the Spanish warships had to find a place to anchor off the island of Corsica, which was then controlled by Genoa. But because a rebellion had started on Corsica, it took five months for some of the Jesuits to finally step onto land.

Several historians have estimated that 6,000 Jesuits were deported. But it's not clear if this number includes only Spain or also its overseas colonies (like Mexico and the Philippines). Jesuit historian Hubert Becher claims that about 600 Jesuits died during their journey and waiting period.

In Naples, King Carlos's minister Bernardo Tanucci followed a similar plan: On November 3, the Jesuits, without any accusation or trial, were marched across the border into the Papal States and threatened with death if they returned.

Historian Charles Gibson calls the Spanish king's expulsion of the Jesuits a "sudden and devastating move" to show royal control. The Jesuits became an easy target for the king's efforts to gain more control over the church. Also, some other religious groups and civil authorities were against them and did not protest their expulsion.

Besides 1767, the Jesuits were suppressed and banned two more times in Spain, in 1834 and 1932. Spanish ruler Francisco Franco ended the last suppression in 1938.

Economic Impact on the Spanish Empire

The ending of the Jesuit order had long-lasting economic effects in the Americas. This was especially true in areas where they had their missions or reductions, which were remote areas mainly populated by native peoples like in Paraguay and Chiloé Archipelago. In Misiones, in modern-day Argentina, their suppression led to the native Guaranís living in the reductions being scattered and enslaved. It also caused a long-term decline in the yerba mate industry, which only recovered in the 1900s.

In Ocoa, Valparaíso Region, Chile, old stories say Jesuits left behind a large hidden treasure (entierro) after they were suppressed.

With the suppression of the Society of Jesus in Spanish America, Jesuit vineyards in Peru were sold off. However, the new owners did not have the same skills as the Jesuits, which led to a decrease in the production of wine and pisco (a type of brandy).

Malta Suppresses the Jesuits

Malta was at that time under the rule of the Kingdom of Sicily. Grandmaster Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, who was Portuguese himself, followed suit. He expelled the Jesuits from the island and took their property. These assets were used to establish the University of Malta by an order signed by Pinto on November 22, 1769. This had a lasting impact on Malta's social and cultural life. The Church of the Jesuits (in Maltese Knisja tal-Ġiżwiti), one of the oldest churches in Valletta, still keeps this name today.

Parma Expels the Jesuits

The independent Duchy of Parma was the smallest Bourbon court. It was so aggressive in its opposition to church power after the news of the Jesuits' expulsion from Naples that Pope Clement XIII issued a public warning against it on January 30, 1768. He threatened the Duchy with church punishments. Because of this, all the Bourbon courts turned against the Holy See (the Pope's authority), demanding that the Jesuits be completely dissolved. Parma expelled the Jesuits from its lands and took their possessions.

Jesuits Dissolved in Poland and Lithuania

The Jesuit order was ended in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1773. However, in the areas taken over by the Russian Empire during the First Partition of Poland, the Society was not dissolved. Russian Empress Catherine ignored the Pope's order. In the Commonwealth, much of the Society's property was taken over by the Commission of National Education, which was the world's first Ministry of Education. Lithuania followed the suppression order.

The Pope Officially Suppresses the Jesuits in 1773

After the Jesuits were suppressed in many European countries and their overseas empires, Pope Clement XIV issued a special papal letter on July 21, 1773, in Rome. It was called Dominus ac Redemptor Noster. That order included the following statement:

{{{1}}}

Jesuits Continue in Prussia

Frederick the Great of Prussia refused to allow the Pope's document of suppression to be shared in his country. The order continued in Prussia for several years after the official suppression, though it did dissolve before it was brought back in 1814.

Jesuits Continue in North America

Many individual Jesuits continued their work as Jesuits in Quebec, even though the last one died in 1800. The 21 Jesuits living in North America signed a document agreeing to Rome's decision in 1774. In the United States, schools and colleges continued to be run and founded by Jesuits.

Russia Resists the Suppression

In Imperial Russia, Catherine the Great refused to allow the Pope's document of suppression to be shared. She even openly defended the Jesuits from being dissolved. The Jesuit group in Belarus received her support. They ordained priests, ran schools, and opened housing for new members and those in advanced training. Catherine's successor, Paul I, successfully asked Pope Pius VII in 1801 for official approval of the Jesuit work in Russia. The Jesuits, led first by Franciszek Kareu, then by Gabriel Gruber, and after his death by Tadeusz Brzozowski, continued to grow in Russia under Alexander I. They added missions and schools in Astrakhan, Moscow, Riga, Saratov, and St. Petersburg, and throughout the Caucasus and Siberia. Many former Jesuits from all over Europe traveled to Russia to join the approved order there.

Alexander I stopped supporting the Jesuits in 1812, but with the restoration of the Society in 1814, this only temporarily affected the order. Alexander eventually expelled all Jesuits from Imperial Russia in March 1820.

Russia Helps Restore Jesuits in Europe and North America

With the support of the "Russian Society," Jesuit groups were effectively brought back in the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1803, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in 1803, and the United States in 1805. "Russian" groups were also formed in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

Austria and Hungary Agree to Suppression

The Secularization Decree by Joseph II (Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790) was issued on January 12, 1782, for Austria and Hungary. It banned several monastic orders that were not involved in teaching or healing. It closed 140 monasteries (homes to 1484 monks and 190 nuns). The banned monastic orders included Jesuits, Camaldolese, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Carmelites, Carthusians, Poor Clares, Order of Saint Benedict, Cistercians, Dominican Order (Order of Preachers), Franciscans, Pauline Fathers, and Premonstratensians. Their wealth was taken over by the Religious Fund.

His actions against church power and his liberal ideas caused Pope Pius VI to visit Joseph II in March 1782. Joseph II received the Pope politely and presented himself as a good Catholic but refused to be influenced.

Jesuits Are Restored

As the Napoleonic Wars were ending in 1814, the old political order of Europe was largely brought back at the Congress of Vienna. This happened after years of fighting and revolution, during which the Church had been treated badly and misused under the rule of Napoleon. With the political situation in Europe changed, and with the powerful kings who had called for the suppression of the Society no longer in power, Pope Pius VII issued an order restoring the Society of Jesus in the Catholic countries of Europe. The Society of Jesus itself decided at its first big meeting after the restoration to keep its organization just as it had been before the suppression was ordered in 1773.

After 1815, with the Restoration, the Catholic Church again began to play a more accepted role in European politics. Nation by nation, the Jesuits were re-established.

The modern view is that the order's suppression happened because of political and economic disagreements, rather than religious arguments. It was also about countries wanting to be more independent from the Catholic Church. The expulsion of the Society of Jesus from the Catholic nations of Europe and their colonies is also seen as one of the early signs of the new secular (non-religious) way of thinking during the Age of Enlightenment. This thinking reached its peak with the anti-church ideas of the French Revolution. The suppression was also seen as an attempt by kings to gain control of money and trade that the Society of Jesus had previously controlled. Catholic historians often point to a personal conflict between Pope Clement XIII (1758–1769) and his supporters within the church, and the powerful cardinals supported by France.

Images for kids

-

Motín de Esquilache, Madrid, attributed to Francisco de Goya (around 1766, 1767)

See also

In Spanish: Supresión de la Compañía de Jesús para niños

In Spanish: Supresión de la Compañía de Jesús para niños

- Society of the Faith of Jesus

- Jesuit clause – clause banning Jesuits from Norway from 1814 to 1956

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |