History of yerba mate facts for kids

The history of yerba mate is a long and interesting journey! It began even before Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas, in a region now known as Paraguay. This special plant quickly became popular in the Spanish colonies of South America. Growing yerba mate was tricky at first, but people learned how to farm it in the mid-1600s. Later, around 1900, its production became a big industry.

Yerba mate became very popular in the Spanish colony of Paraguay in the late 1500s. Both Spanish settlers and the native Guaraní people enjoyed it. The Guaraní had already been drinking it before the Spanish arrived. In the 1600s, mate drinking spread to the Platine region (which includes parts of modern-day Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil), and from there to Chile and Peru. Because so many people drank it, yerba mate became Paraguay's most important product, even more valuable than tobacco.

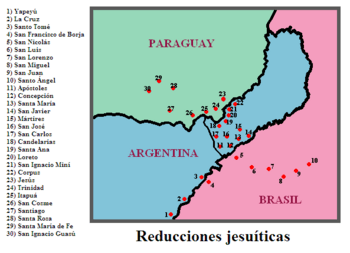

At first, people gathered mate from wild plants, often using the labor of native people. In the mid-1600s, a group called the Jesuits figured out how to grow the plant on farms. They set up these farms in their missions in Misiones Province. This created a lot of competition with those who gathered wild mate.

When the Jesuits were forced to leave in the 1770s, their farms and their secrets for growing mate were lost. Yerba mate remained very important for Paraguay's economy after it became independent. However, the Paraguayan War (1864–1870) badly damaged the country, both economically and by reducing its population. After this, Brazil became the main producer of yerba mate.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, people in Brazil and Argentina learned how to grow mate again, leading to modern farming methods. In the 1930s, Brazilian farmers started focusing on coffee instead. Argentina, which had always been the biggest buyer of mate, then became the largest producer. This helped the Misiones Province recover, where the Jesuits once had their farms. Today, Brazil is the world's biggest producer of mate, followed by Argentina and Paraguay.

Contents

Early Uses of Yerba Mate

Before the Spanish came, the Guaraní people, who lived where the yerba mate plant naturally grows, used it for medicine. Some traces of yerba mate have even been found in an ancient tomb in Peru, suggesting it was a special drink for important people.

The first Europeans to settle in the Guaraní lands were the Spanish, who founded the city of Asunción in 1537. This new colony didn't have much trade with the outside world, so the Spanish settlers formed closer ties with the local tribes. It's not clear exactly when the Spanish started drinking mate, but by the late 1500s, it was very common.

By 1596, drinking mate had become so popular in Paraguay that a member of the local council (called a cabildo) wrote to the governor. He said that "the bad habit of drinking yerba has spread so much among the Spaniards, their women and children." He added that unlike the native people who drank it once a day, the Spanish drank it all the time. The letter also claimed that Spanish settlers would sell their clothes, weapons, and horses, or go into debt, just to get yerba mate.

Mate Spreads Across South America (1600–1650)

In the early 1600s, yerba mate became the main product exported from the Guaraní lands. It was more important than sugar, wine, and tobacco, which had been the main exports before.

The governor of the Río de la Plata tried to stop the growing mate industry in the early 1600s. He thought it was an unhealthy habit and that too many native workers were being used to gather it. He ordered an end to its production and asked the Spanish King for approval. However, the King said no, and the people involved in mate production ignored the ban.

Unlike other plants like cocoa and coffee, yerba mate was not grown on farms at first. People gathered it from wild plants for a long time, even into the 1800s. However, the Jesuits were the first to successfully grow it on farms in the mid-1600s.

Until 1676, the main place for mate production was the native town of Maracayú, northeast of Asunción. This area had many wild yerba mate forests. Settlers from Asunción controlled the production there. However, Maracayú became a place of conflict when settlers from other towns moved into the area, claiming it as their own.

In the 1630s, the conflict got worse when settlers and Jesuits from other areas had to flee to Maracayú because of attacks. In Maracayú, these new settlers made mate their main way to earn money. This caused more conflict with the original settlers from Asunción. The fighting ended in 1676 when more attacks made Maracayú a dangerous border area. The settlers from Maracayú then moved south, forming the modern city of Villarrica. This new area became the center of the mate industry.

As the conflict in Maracayú happened, mate drinking spread beyond Paraguay. It first went to the trading center of Río de la Plata, and from there to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, and Chile. Mate became an important product in many cities across colonial South America. Native Guaraní soldiers serving in the Army of Arauco might have helped make the drink popular in southern Chile after this army was formed in 1604.

Mate arrived in Chile by land, and small amounts were sent north by ship from Valparaíso to ports like El Callao, Guayaquil, and Panamá. During the 1600s, taxes on mate became an important source of money for Paraguay, Santa Fé, and Buenos Aires. It was heavily taxed, including a tithe (a church tax), alcabala (a sales tax), and city taxes. In 1680, the Spanish King added a special tax on yerba mate to help pay for Buenos Aires' defenses.

When mate production moved south to Villarrica, Asunción lost its position as the only place for exporting mate down the Paraná River. Before, transporting mate down the Paraná was hard, so it was brought to Asunción on the Paraguay River, which was easy to travel on all the way to Río de la Plata. The local government of Asunción tried to make all mate produced north of the Tebicuary River pass through their city. But the Villarrica settlers and the Spanish King mostly ignored Asunción's complaints.

Jesuit Era and Growing Mate (1650–1767)

In the late 1500s, the Jesuits began setting up special settlements called reductions in the lands of the Guaraní people. Their goal was to teach them about Catholicism. These Jesuit missions were mostly self-sufficient, but they needed money to pay taxes and buy things they couldn't make.

In the early 1600s, the Jesuits had supported the governor's ban on mate production. But by the mid-1600s, they became strong competitors to the mate gatherers who had a monopoly on the product. In 1645, the Jesuits successfully asked the Spanish King for permission to produce and export yerba mate.

At first, the Jesuits followed the usual method: they sent thousands of Guaraní people on long trips into the forests to gather mate from wild trees. Many native people became sick or died during these trips. However, from the 1650s to the 1670s, the Jesuits managed to figure out how to grow the mate plant on farms. This was something others had found very difficult.

The Jesuits kept their method for growing mate a secret. It seems they either fed the seeds to birds or copied how birds' digestive systems helped the seeds grow. The Jesuits gained many business advantages over their competitors. Besides successfully growing mate on farms, their missions were closer to important trade centers like Santa Fé and Buenos Aires. They also managed to get special permission to avoid certain taxes, like the tithe, alcabala, and the extra tax from 1680.

These special privileges caused problems with the Paraguayan cities of Asunción and Villarrica. These cities accused the Jesuits of selling too much cheap yerba mate in the market. This led to limits on how much mate the Jesuits could export. However, they often exported more than they were allowed. By the time the Jesuits were forced to leave, they were exporting four times the legal amount. The Jesuits officially said they didn't sell mate for profit, only to cover their basic needs and taxes. They blamed the Paraguayans for causing prices to drop and said that merchants preferred their mate because it was better quality, not just cheaper.

Because there wasn't much money available, yerba mate, along with honey, corn, and tobacco, was sometimes used as money in the Jesuit missions.

Mate's Growth and Changes (1767–1870)

After the Jesuits were forced to leave in 1767, the areas where they had grown mate began to decline. The farms were not managed well, and the native Guaraní people who lived in the missions scattered. With the Jesuits gone and new owners mismanaging the farms, Paraguay became the main producer of yerba mate. However, the Jesuit farming system didn't last. For most of the 18th and 19th centuries, mate was still mostly gathered from wild plants.

Concepción, a city founded in Paraguay in 1773, became a major export port. It had a huge area of untouched wild mate plants to its north. As part of new rules from the Spanish King, free trade was allowed within the Spanish Empire in 1778. This, along with a tax change in 1780, led to more trade in Spanish South America, which helped the mate industry. By the 1770s, drinking mate had spread as far as Cuenca, in what is now Ecuador.

During the colonial period, mate didn't become as popular in Europe as cocoa, tea, and coffee. In 1774, a Jesuit wrote that "many" people in Portugal and Spain drank mate, and many in Italy liked it too. In the 1800s, French scientists Aimé Bonpland and Augustin Saint-Hilaire studied the plant. In 1819, Saint-Hilaire gave yerba mate its scientific name: Ilex paraguariensis.

Expensive mate cups made of silver in colonial South America were mostly crafted by local silversmiths. These artisans followed European styles like Baroque and Neoclassicism.

After gaining independence, Paraguay lost its top spot as a mate producer to Brazil and Argentina. Argentina, however, faced a mate crisis. When Argentina became independent, it had the most mate drinkers in the world, but the mate industry in Misiones Province, where most Jesuit missions had been, was declining. Because Argentina's production fell while demand kept growing, it had to rely heavily on its neighbors for mate in the mid-1800s. Yerba mate was imported to Argentina from Brazil's Paraná highlands. This mate was called Paranaguá after its shipping port.

In Paraguay, yerba mate remained a major product after independence. But the industry's focus moved from the farms and wild plants of Villarrica, first to Concepción in the late colonial period, and then to San Pedro by 1863. During the rule of Carlos Antonio López (1844–1862), the yerba mate business was managed by military leaders. They could either harvest mate as a state business or give permission to others.

The start of the Paraguayan War (1864–1870) caused a huge drop in mate harvesting in Paraguay, estimated at 95% between 1865 and 1867, because so many men joined the army. It's said that during the war, soldiers from all sides drank yerba mate to help with hunger and stress from fighting. After the war against Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay, Paraguay was ruined both in terms of people and economy. Foreign business owners then took control of mate production in Paraguay. The large areas of land Paraguay lost in the war to Argentina and Brazil were mostly rich in yerba mate.

In Chile, where mate drinking had become very popular during colonial times, its popularity slowly faded after independence. Drinks popular in Europe, like coffee and tea, entered the country through its busy ports. Tea and coffee first became popular among the wealthy classes in Chile. The first coffee shop in Chile opened in Santiago in 1808. A German botanist wrote in 1827 that in a rich Chilean family, the older people drank yerba mate, while the younger ones preferred Chinese tea.

The British consul noticed the decline in mate drinking in 1875, saying that "imports of Paraguayan tea" were "steadily falling off." Yerba mate was generally cheaper than tea and coffee and remained popular in Chile's countryside. Despite its decline, mate was still important in the port city of Coquimbo. A unique style of mate cup, known as mate coquimbano, appeared there in the early 1800s. Yerba mate was widely consumed in the cold, mountainous areas of Chile, and in the south of the country. It was even one of the basic supplies found in the mountain shelters built in the 1760s for the Trans-Andean postal system.

Modern Mate: Factories and New Lands (1870–1950)

With Paraguay's economy ruined and Argentina producing very little, Brazil became the main producer of yerba mate by the late 1800s. In the 1890s, yerba mate farms became important again when new plantations were started in Mato Grosso do Sul.

In the early 1900s, Argentina's mate production began to recover. It grew from less than 1 million kg in 1898 to 20 million kg in 1929 in Misiones Province alone. In the first half of the 20th century, Argentina had a government program to bring people to Misiones Province and restart the mate industry. Small plots of land were given to foreign settlers, mostly from Central and Eastern Europe.

In the 1930s, Brazil shifted from mate to coffee production because coffee brought in more money. This left the revived Argentine mate industry as the biggest producer, which helped Argentina's economy since it was also the largest buyer of mate.

Syrian and Lebanese immigrants who moved to Argentina shared the habit of drinking mate with their home countries. It became especially popular among the Druze people there.

See also

In Spanish: Historia de la yerba mate para niños

In Spanish: Historia de la yerba mate para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |