Gregor MacGregor facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gregor MacGregor

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 24 December 1786 Stirlingshire, Scotland, Great Britain |

| Died | 4 December 1845 (aged 58) Caracas, Venezuela |

| Place of burial |

Caracas, Venezuela

|

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/ |

|

| Rank | Divisional general (from 1817) |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards | Order of the Liberators (Venezuela) |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Other work | Involved in Amelia Island affair of 1817. Claimed to be Cazique of Poyais from 1821 to 1837. |

General Gregor MacGregor (born December 24, 1786 – died December 4, 1845) was a Scottish soldier and adventurer. He is best known for a huge trick he played between 1821 and 1837. He tried to get people from Britain and France to invest their money and move to a made-up country called "Poyais" in Central America. He claimed to be its ruler, the "Cazique".

Hundreds of people put their savings into fake government bonds and land papers for Poyais. About 250 people actually sailed to MacGregor's invented country in 1822–23. They found only an untouched jungle, not the developed land they were promised. More than half of them died. MacGregor's Poyais scheme is often called one of the biggest tricks in history.

MacGregor was an officer in the British Army from 1803 to 1810, fighting in the Peninsular War. In 1812, he joined the side fighting for independence in the Venezuelan War of Independence. He quickly became a general. For the next four years, he fought against the Spanish for both Venezuela and New Granada. One of his successes was a tough month-long fighting retreat through northern Venezuela in 1816.

In 1817, he captured Amelia Island in Florida. He claimed to be conquering Florida from the Spanish and announced a short-lived "Republic of the Floridas". Later, in 1819, he led two very difficult operations in New Granada. Both ended with him leaving his British volunteer troops behind.

When he returned to Britain in 1821, MacGregor claimed that King George Frederic Augustus of the Mosquito Coast had made him the Cazique of Poyais. He described Poyais as a developed colony with British settlers. When the British newspapers reported his trick in late 1823, after fewer than 50 survivors returned, some of his victims still defended him. They said the general had been let down by others. In 1826, a French court tried MacGregor and three others for fraud. Only one of his helpers was found guilty. MacGregor was found not guilty and tried smaller Poyais schemes in London for the next ten years. In 1838, he moved to Venezuela, where he was welcomed as a hero. He died in Caracas in 1845, at 58 years old. He was buried with full military honors in Caracas Cathedral.

Contents

Early Life and Military Service

Family Background and Childhood

Gregor MacGregor was born on Christmas Eve in 1786. His family home was Glengyle, near Loch Katrine in Stirlingshire, Scotland. His father, Daniel MacGregor, was a sea captain for the East India Company. His mother was Ann Austin. The family was Roman Catholic and part of the Clan Gregor. This clan had been banned by King James VI and I in 1604, but the ban was lifted in 1774.

During the ban, MacGregors were not allowed to use their own family name. Many, including Gregor's famous great-great-uncle Rob Roy, took part in rebellions against the king. Gregor later claimed that one of his ancestors survived the Darien scheme of 1698. This was a Scottish attempt to start a colony in Panama that failed badly. Gregor's grandfather, also named Gregor, was known as "the Beautiful." He served well in the British Army under the name Drummond. He later helped restore the clan's name and place in society.

We don't know much about MacGregor's childhood. His father died in 1794, and his mother raised him and his two sisters. He probably spoke mostly Gaelic when he was very young. He likely learned English after starting school around age five. MacGregor later said he studied at the University of Edinburgh from 1802 to 1803. There are no records of him getting a degree, but it's possible he attended.

Joining the British Army

MacGregor joined the British Army in April 1803, when he was 16. This was the youngest age allowed. His family bought him a position as an ensign in the 57th (West Middlesex) Regiment of Foot. This probably cost about £450. MacGregor joined the army just as the Napoleonic Wars were starting. Southern England was being prepared for a possible French invasion. MacGregor's regiment was stationed in Ashford, Kent.

In February 1804, less than a year after joining, MacGregor was promoted to lieutenant. This promotion usually took up to three years. Later that year, his regiment was sent to Gibraltar.

Around 1804, MacGregor met Maria Bowater. She was the daughter of a Royal Navy admiral and came from a wealthy family. Gregor and Maria married in June 1805 in London. Two months later, MacGregor bought the rank of captain for about £900. This meant he didn't have to wait seven years for the promotion.

His regiment stayed in Gibraltar from 1805 to 1809. During this time, MacGregor became obsessed with uniforms and medals. This made him unpopular with his fellow soldiers. He even ordered that no soldier could leave their living area without wearing their full uniform.

In 1809, the 57th Foot was sent to Portugal to help the Anglo-Portuguese Army. They were fighting to push the French out of Spain during the Peninsular War. MacGregor's regiment arrived in Lisbon on July 15. By September, they were guarding Elvas, near the Spanish border. Soon after, MacGregor was temporarily moved to the 8th Line Battalion of the Portuguese Army. He served there as a major from October 1809 to April 1810.

Some say this move happened after an argument between MacGregor and a higher-ranking officer. He formally left the British Army on May 24, 1810. He got back the £1,350 he had paid for his ranks and returned to Britain. The 57th Foot later became famous in the Battle of Albuera in 1811, earning the nickname "the Die-Hards." MacGregor often talked about his connection to them, even though he had left a year before.

From Edinburgh to Caracas

Back in Britain, 23-year-old MacGregor and his wife moved to Edinburgh. There, he started calling himself "Colonel" and wore a Portuguese knight's badge. He rode around the city in a very fancy coach. When he couldn't gain high social status in Edinburgh, MacGregor moved back to London in 1811. He then began calling himself "Sir Gregor MacGregor, Bart." He falsely claimed to be the leader of the MacGregor clan. He also hinted at family ties to dukes and earls. This wasn't true, but he still managed to seem respectable in London society.

In December 1811, Maria MacGregor died. MacGregor lost his main income and the support of her powerful family. His options were limited. He couldn't get engaged to another wealthy woman so soon. Going back to farming in Scotland seemed boring. His only real experience was military, but leaving the British Army had been difficult.

MacGregor became interested in the revolts against Spanish rule in Latin America. Especially in Venezuela, where seven of ten provinces had declared independence in July 1811. This started the Venezuelan War of Independence. The Venezuelan revolutionary General Francisco de Miranda had been celebrated in London. MacGregor might have met him.

Seeing how Miranda was treated in London, MacGregor thought adventures in the New World could make him famous too. He sold the small Scottish estate he had inherited. He sailed for South America in early 1812. He stopped in Jamaica, but was not welcomed into society there. After a comfortable stay in Kingston, he sailed to Venezuela and arrived in April 1812.

Adventures in South America

Fighting for Venezuela

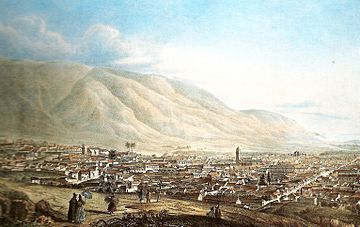

MacGregor arrived in Caracas, Venezuela's capital, two weeks after a huge earthquake destroyed much of the city. Spanish royalist armies were taking control of parts of the country. The revolutionary government was losing support. MacGregor stopped pretending to be a Scottish baronet. He thought it might hurt his image as a supporter of the new republic. But he still called himself "Sir Gregor," claiming he was a knight of the Portuguese Order of Christ.

He offered his help directly to Miranda in Caracas. As a former British Army officer, he was quickly welcomed. He was given command of a cavalry battalion with the rank of colonel. In his first battle, MacGregor and his cavalry defeated a royalist force west of Maracay. Later battles were not as successful. But the revolutionary leaders were still happy to have this exciting Scottish officer on their side.

MacGregor married Josefa Antonia Andrea Aristeguieta y Lovera in Maracay on June 10, 1812. She was from a well-known Caracas family and a cousin of the revolutionary leader Simón Bolívar. By the end of June, Miranda had promoted MacGregor to brigadier-general. But the revolution was failing. In July, the royalists took the important port of Puerto Cabello from Bolívar. The republic surrendered. In the confusion, Miranda was captured by the Spanish. The remaining revolutionary leaders, including MacGregor and Josefa, escaped to the Dutch island of Curaçao on a British ship. Bolívar joined them later that year.

Defending Cartagena in New Granada

With Miranda in a Spanish prison, Bolívar became the new leader of the Venezuelan independence movement. He decided they needed time to prepare before returning to the mainland. MacGregor got bored in Curaçao. He decided to offer his help to General Antonio Nariño's republican armies in New Granada, Venezuela's neighbor to the west. He took Josefa to stay in Jamaica. Then he traveled to Nariño's base in Tunja in the eastern Andes.

Miranda's name helped MacGregor get a new position in New Granada's army. He was given command of 1,200 men in the Socorro area, near the border with Venezuela. There wasn't much fighting there. Nariño's main forces were fighting around Popayán in the southwest, where the Spanish had a large army. Some reports say MacGregor improved the soldiers' training. But some under his command did not like him. One official called him a "bluffer" and a "Quixote."

While MacGregor was serving in New Granada, Bolívar gathered an army of Venezuelan exiles and local troops in Cartagena. He then captured Caracas on August 4, 1813. But the royalists quickly fought back and crushed Bolívar's second republic in mid-1814. Nariño's New Granadian forces surrendered around the same time. MacGregor went back to Cartagena, which was still controlled by the revolutionaries. He led native troops in destroying villages and farms to prevent the Spanish from using them.

A Spanish force of about 6,000 soldiers arrived in late August 1815 and attacked the city. They tried many times to defeat the 5,000 defenders but failed. So, they decided to surround the city and cut off its supplies. MacGregor played an "honorable" part in the defense, though he wasn't the main leader.

By November 1815, only a few hundred men in Cartagena could still fight. The defenders decided to use their dozen gunboats to break through the Spanish fleet and escape to the open sea. They would leave the city to the royalists. MacGregor was chosen as one of the three commanders for this plan. On the night of December 5, 1815, the gunboats sailed into the bay. They fought their way through the smaller Spanish ships and avoided the larger ones. All the gunboats escaped and headed for Jamaica.

Fighting for Bolívar in Venezuela

British merchants in Jamaica, who had ignored MacGregor in 1812, now welcomed him as a hero. He told many exaggerated stories about his part in the Cartagena siege. Some people thought he had personally led the city's defense. One Englishman even called him the "Hannibal of modern Carthage." Around New Year 1816, MacGregor and his wife went to Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic). Bolívar was gathering a new army there.

Bolívar welcomed MacGregor back into the Venezuelan Army as a brigadier-general. He included him in an expedition that left Aux Cayes on April 30, 1816. MacGregor helped capture the port town of Carúpano. But he is not mentioned in Bolívar's official battle report. After the Spanish were driven from many towns in central Venezuela, MacGregor was sent to the coast west of Caracas in July 1816. His job was to recruit native tribesmen. On July 18, eight days after the Spanish defeated Bolívar's main force, MacGregor decided to retreat hundreds of miles east to Barcelona.

Two Spanish armies chased MacGregor as he retreated. But they could not break his rear guard. He had no carts and few horses, so he had to leave his wounded soldiers behind. Late on July 27, a Spanish force blocked MacGregor's path at Chaguaramas. This was south of Caracas and about a third of the way to Barcelona. MacGregor led his men in a fierce charge that made the Spanish retreat. He then continued towards Barcelona. The Spanish stayed in the town until July 30, giving MacGregor a two-day head start. They caught up with him on August 10.

MacGregor placed his 1,200 men, mostly native archers, behind a marsh and a stream. The Spanish cavalry got stuck in the marsh, and the archers fought off the infantry with arrows. After three hours, MacGregor charged and defeated the Spanish. MacGregor's group was helped the rest of the way to Barcelona by parts of the main revolutionary army. They arrived on August 20, 1816, after a 34-day march.

This march was the peak of MacGregor's fame in South America. He had led his troops with great success. It was a "remarkable feat" that showed "genuine military skill." With Bolívar back in Aux Cayes, Manuel Piar was in overall command of the republican armies in Venezuela. On September 26, Piar and MacGregor defeated the Spanish army at El Juncal. But MacGregor and Piar had disagreements about how to fight the war. In early October 1816, MacGregor left with Josefa for Margarita Island, hoping to join General Juan Bautista Arismendi.

Soon after, he received a letter from Bolívar. It said: "The retreat which you had the honour to conduct is in my opinion superior to the conquest of an empire... Please accept my congratulations for the prodigious services you have rendered my country." MacGregor's march to Barcelona remained famous in South American revolutionary stories for years. The retreat also earned him the nickname "Xenophon of the Americas."

The Florida Republic and Amelia Island

Arismendi suggested to MacGregor that capturing a port in East or West Florida (which were Spanish colonies) could be a good starting point for revolutionary actions elsewhere in Latin America. MacGregor liked the idea. After trying to recruit in Haiti, he sailed with Josefa to the United States. He wanted to raise money and volunteers there. Soon after he left in early 1817, another letter arrived in Margarita from Bolívar. It promoted MacGregor to divisional general and gave him the Orden de los Libertadores (Order of the Liberators). It also asked him to return to Venezuela. MacGregor did not know about this for two years.

On March 31, 1817, in Philadelphia, MacGregor received a document from three men who claimed to represent the Latin American republics. They called themselves the "deputies of free America." They asked MacGregor to take control of "both the Floridas, East and West" as soon as possible. Florida's future was not clear. MacGregor thought Floridians would want to join the US, and that the US would secretly support him.

MacGregor gathered several hundred armed men for this plan in the Mid-Atlantic states, South Carolina, and especially Savannah, Georgia. He also raised $160,000 by selling "scripts" to investors. These promised fertile land in Florida or their money back with interest. He decided to first attack Fernandina. This was a small town with a good harbor at the very northern tip of Amelia Island. It had about 40% of East Florida's population. He expected little resistance from the small Spanish army there.

MacGregor left Charleston on a ship with fewer than 80 men, mostly US citizens. He led the landing party himself on June 29, 1817. He said: "I shall sleep either in hell or Amelia tonight!" The Spanish commander at Fort San Carlos had 51 men and several cannons. He greatly overestimated MacGregor's force and surrendered without a fight.

Few of Amelia's residents supported MacGregor, but there was little resistance. Most simply left for mainland Florida or Georgia. MacGregor raised a flag with a green cross on a white background. He called it the "Green Cross of Florida." On June 30, he issued a statement asking the island's people to return and support him. This was mostly ignored. So was a second statement where MacGregor congratulated his men and urged them to "free the whole of the Floridas from Tyranny and oppression."

MacGregor announced a "Republic of the Floridas" with himself as the head of the government. He tried to tax the local pirates' stolen goods. He also tried to raise money by taking and selling dozens of enslaved people found on the island. His soldiers' morale dropped when he banned looting. Most of his recruits were still in the US. American authorities stopped many of them from leaving port. MacGregor could only gather 200 men on Amelia. His officers wanted to invade mainland Florida, but he said they didn't have enough men, weapons, or supplies.

Eighteen men sent to explore around St Augustine in late July 1817 were killed, wounded, or captured by the Spanish. Discipline among MacGregor's troops fell apart. They were paid first with "Amelia dollars" he had printed, and then not at all.

Spanish forces gathered on the mainland across from Amelia. On September 3, 1817, MacGregor and most of his officers decided the situation was hopeless. They would abandon the plan. MacGregor told his men he was leaving, saying he had been "deceived by my friends." He gave command to one of his officers, Jared Irwin. MacGregor boarded a ship with his wife on September 4, 1817, while an angry crowd insulted him. He waited offshore for a few days, then left on September 8.

Two weeks later, the MacGregors arrived in Nassau in the Bahamas. There, he had special medals made with the Green Cross symbol. They had Latin words like "Amelia, I Came, I Saw, I Conquered." He did not try to repay those who had funded the Amelia expedition. Irwin's troops defeated two Spanish attacks. Then, 300 men under Louis-Michel Aury joined them. Aury held Amelia for three months before surrendering to American forces. The Americans held the island for Spain until Florida was purchased in 1819.

Newspaper reports about the Amelia Island affair were very wrong. This was partly because MacGregor spread false information. He claimed his sudden departure was because he had sold the island to Aury for $50,000. Josefa gave birth to their first child, a boy named Gregorio, in Nassau on November 9, 1817. MacGregor learned about British volunteer groups being formed in London for the Latin American revolutions. He was excited by the idea of leading British troops again. He sailed home with Josefa and Gregorio, landing in Dublin on September 21, 1818. From there, he went back to London.

Disasters at Porto Bello and Rio de la Hacha

The Venezuelan government's representative in London borrowed £1,000 for MacGregor. This money was to hire and transport British troops for service in Venezuela. But MacGregor wasted these funds in a few weeks. A London banker, Thomas Newte, took responsibility for the debt. He agreed that MacGregor should take troops to New Granada instead. MacGregor funded his trip by selling officer positions at lower prices than the British Army. He gathered soldiers by offering them big financial rewards.

MacGregor sailed for South America on November 18, 1818, on a ship called the Hero. Fifty officers and over 500 troops, many of them Irish, followed the next month. They had very few weapons or supplies. The men almost rebelled in Aux Cayes in February 1819. MacGregor had promised them 80 silver dollars each upon arrival, but he didn't have the money. MacGregor convinced South American merchants in Haiti to give him funds, weapons, and ammunition. But he delayed, and only ordered the ships to sail for San Andrés on March 10. This island was off the Spanish-controlled Isthmus of Panama.

MacGregor went to Jamaica first to arrange a place for Josefa and Gregorio. He was almost arrested there for smuggling weapons. He joined his troops on San Andrés on April 4. The delay had caused more arguments among the soldiers. MacGregor improved morale by announcing they would attack Porto Bello on the New Granadian mainland the next day.

Colonel Rafter landed with 200 men near Porto Bello on April 9. He outsmarted a similar number of Spanish defenders during the night. He marched into Porto Bello without a fight on April 10. MacGregor, watching from one of the ships, quickly came ashore when he saw Rafter's victory signal. He then issued a grand statement: "Soldiers! Our first conquest has been glorious, it has opened the road to future and additional fame."

Rafter urged MacGregor to march on Panama City. But MacGregor didn't make many plans to continue the fight. He spent most of his time on details for a new knightly order he was creating. Its symbol would be a Green Cross. The troops became angry again when more promised money didn't appear. MacGregor eventually paid each man $20, but this didn't help discipline much.

MacGregor's troops did not patrol well. This allowed the Spanish to march straight into Porto Bello early on April 30, 1819. MacGregor was still in bed when the Spanish found his soldiers training in the main square and opened fire. MacGregor woke up, threw his bed and blankets out the window onto the beach, and jumped out after them. He then tried to paddle to his ships on a log. He passed out and would have drowned if one of his naval officers hadn't picked him up and brought him aboard the Hero.

MacGregor later claimed that he immediately raised his flag over the Hero and sent orders to Rafter not to surrender. However, others say Rafter only received these orders after he had contacted MacGregor on the Hero. Rafter, in the fort with 200 men, kept firing and waited for his commander to shoot at the Spanish from the ships. But to Rafter's surprise, MacGregor instead ordered his fleet to turn around and sail away.

Abandoned, Colonel Rafter and the rest of MacGregor's army had to surrender. Most of the surviving officers and troops became miserable prisoners. Rafter was later shot with 11 other officers for planning to escape.

MacGregor went first to San Andrés, then to Haiti. He gave out made-up awards and titles to his officers. He planned a trip to Rio de la Hacha in northern New Granada. He was delayed in Haiti by an argument with his naval commander, Hudson. When Hudson got sick, MacGregor put him ashore, took control of the Hero (which Hudson owned), and renamed it El MacGregor. He told Haitian officials that his captain's "insanity and mutiny" forced him to take the ship. MacGregor sailed the hijacked ship to Aux Cayes, then sold it because it was not seaworthy.

Waiting for him in Aux Cayes were 500 officers and soldiers, thanks to recruiters in Ireland and London. But he had no ships to carry them and little equipment. This changed in July and August 1819. First, his Irish recruiter, Colonel Thomas Eyre, arrived with 400 men and two ships. MacGregor made him a general and gave him the Order of the Green Cross. Then, war supplies arrived from London, sent by Thomas Newte on a ship called Amelia.

MacGregor loudly announced his plan to free New Granada, but then he hesitated. The lack of action, food, or pay for weeks made most of the British volunteers go home. MacGregor's force, which had been 900 men at its largest, had shrunk to no more than 250 by the time he directed the Amelia and two other ships to Rio de la Hacha on September 29, 1819. His remaining officers included Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Rafter, who had bought his position hoping to rescue his brother William.

After being driven away from Rio de la Hacha harbor by cannons on October 4, MacGregor ordered a night landing west of the town. He said he would take personal command once the troops were ashore. Lieutenant-Colonel William Norcott led the men onto the beach and waited two hours for MacGregor to arrive, but the general never appeared. Attacked by a larger Spanish force, Norcott fought back and captured the town. MacGregor still refused to leave the ships. He was convinced the flag flying over the fort was a trick. Even when Norcott rowed out to tell him to come into port, MacGregor would not step ashore for over a day. When he finally appeared, many of his soldiers swore at him. He issued another grand statement, which one officer called an "aberration of human intellect." In it, MacGregor called himself "His Majesty the Inca of New Granada."

Events largely repeated what happened earlier at Porto Bello. MacGregor avoided actual command. One officer wrote that "General MacGregor displayed so palpable a want of the requisite qualities... that universal astonishment prevailed." As Spanish forces gathered around the town, Norcott and Rafter decided the situation was hopeless. They left on a captured Spanish ship on October 10, 1819, taking five officers and 27 soldiers and sailors with them. MacGregor called his remaining officers together the next day. He gave them promotions and Green Cross awards. He urged them to help him lead the defense. Immediately afterward, he went to the port, supposedly to escort Eyre's wife and two children to safety on a ship. After putting the Eyres on the Lovely Ann, he boarded the Amelia and ordered the ships out to sea just as the Spanish attacked. General Eyre and the troops left behind were all killed.

MacGregor reached Aux Cayes to find that news of this latest disaster had arrived before him. He was avoided by everyone. A friend in Jamaica, Thomas Higson, told him that Josefa and Gregorio had been forced out of their home. They had to seek shelter in a slave's hut until Higson helped them. MacGregor was wanted in Jamaica for piracy, so he couldn't join his family there. He also couldn't go back to Bolívar. Bolívar was so angry with MacGregor's recent actions that he accused him of treason. He ordered MacGregor to be hanged if he ever set foot on the South American mainland again. MacGregor's location for the six months after October 1819 is unknown. In June 1820, Michael Rafter published a very critical book about MacGregor's adventures in London. He dedicated the book to his brother Colonel William Rafter and the troops abandoned at Porto Bello and Rio de la Hacha. Rafter thought MacGregor was "politically, though not naturally dead." He believed no one would ever join him in his "desperate projects" again.

The Poyais Scheme

The Cazique of Poyais

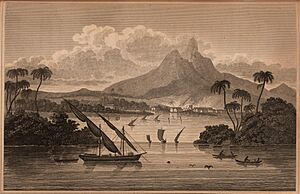

MacGregor's next known location was at the court of King George Frederic Augustus of the Mosquito Coast. This was at Cape Gracias a Dios on the Gulf of Honduras in April 1820. The Miskito people (descendants of African slaves and native people) disliked Spain, just like the British. British officials had crowned their most powerful chiefs as "kings" since the 1600s. These "kings" had little real power. Britain protected them so they could claim the area was under Mosquito rule, stopping Spanish claims. There had been a small British settlement there, but it was abandoned in 1786. By the 1820s, the only sign of past settlement was a small graveyard hidden by the jungle.

On April 29, 1820, King George Frederic Augustus signed a document. It gave MacGregor and his family a large piece of Mosquito land. It was 8 million acres, bigger than Wales, in exchange for rum and jewelry. The land looked nice but was not good for farming or raising animals. It was roughly a triangle. MacGregor named this area "Poyais" after the native Paya or "Poyer" people. In mid-1821, he appeared back in London. He called himself the Cazique of Poyais. "Cazique" is a Spanish-American word for a native chief. MacGregor used it to mean "Prince." He claimed the Mosquito king had given him this title, but both the title and Poyais were his own inventions.

Despite a critical book about MacGregor, London society mostly didn't know about his recent failures. They remembered his successes, like his march to Barcelona. His connection to the "Die-Hards" regiment was recalled, but his questionable early departure from the British Army was not. At this time, Latin America was changing constantly, with new governments appearing. So, it didn't seem impossible that a country called Poyais existed, or that a decorated general like MacGregor could lead it.

MacGregor became popular in London society. Rumors spread that he was partly descended from native royalty. His exotic appeal grew when the striking "Princess of Poyais," Josefa, arrived. She had given birth to a girl named Josefa Anna Gregoria in Ireland. The MacGregors received many invitations, including an official reception from the Lord Mayor of London.

MacGregor said he came to London to attend King George IV's coronation for the Poyers. He also wanted to find investors and immigrants for Poyais. He claimed Poyais had a democratic government, a basic civil service, and an army. He showed interested people what he said was a copy of a statement he had given to the Poyers on April 13, 1821. In it, he announced the 1820 land grant. He said he was leaving for Europe to find investors and colonists, like "religious and moral instructors." He appointed Brigadier-General George Woodbine to be "Vice-Cazique" while he was away. The document ended with: "POYERS! I now bid you farewell for a while... I trust, that through the kindness of Almighty Providence, I shall be again enabled to return amongst you, and that then it will be my pleasing duty to hail you as affectionate friends, and yours to receive me as your faithful Cazique and Father." There is no proof this statement was ever given out on the Mosquito Coast.

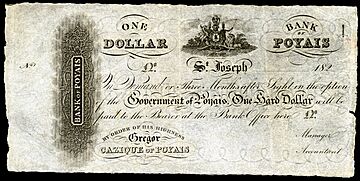

This was the start of what has been called one of the biggest tricks in history: the Poyais scheme. MacGregor created a complex government system for Poyais, with three parts. He designed business and banking systems. He also designed special uniforms for each regiment of the Poyaisian Army. His imaginary country had an honors system, land titles, a coat of arms with Poyers and unicorns, and the same Green Cross flag he used in Florida. By the end of 1821, Major William John Richardson believed MacGregor's story. He became an active helper, offering his estate at Oak Hall to be a British base for the supposed Poyaisian royal family. MacGregor gave Richardson the Order of the Green Cross. He made him an officer in the Poyaisian "Royal Regiment of Horse Guards." He also appointed him the top representative of Poyais in Britain. Richardson's official letter from "Gregor the First, Sovereign Prince of the State of Poyais" was given to King George IV. MacGregor set up Poyaisian offices in London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. These offices sold impressive-looking land certificates to the public and helped organize future emigrants.

A Land of Opportunity?

Many historians believe that Britain in the early 1820s was perfect for MacGregor and his Poyais scheme. After the Battle of Waterloo and the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the British economy was growing. Interest rates were low. British government bonds offered only 3% interest per year. People who wanted more money invested in riskier foreign debts. After European bonds were popular, the Latin American revolutions brought many new options to the London market. Bonds from Colombia, Peru, Chile, and others offered interest rates as high as 6% per year. This made Latin American investments very popular. A country like the Poyais MacGregor described would fit perfectly into this trend.

MacGregor started a strong sales campaign. He gave interviews to newspapers. He hired publicists to write ads and flyers. He even had songs about Poyais written and sung in the streets of London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. His statement to the Poyers was given out as a flyer.

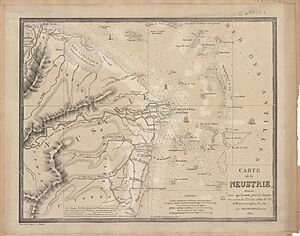

In mid-1822, a 355-page guidebook appeared in Edinburgh and London. It was called Sketch of the Mosquito Shore, Including the Territory of Poyais. It was supposedly written by a "Captain Thomas Strangeways," an aide to the Cazique. But MacGregor himself or his helpers actually wrote it.

The Sketch mostly contained long parts copied from older books about the Mosquito Coast. The new material was misleading or completely made up. MacGregor's publicists said the Poyaisian climate was "remarkably healthy" and "agree[ed] admirably with the constitution of Europeans." They claimed it was a spa place for sick colonists from the Caribbean. The soil was supposedly so fertile that a farmer could get three maize harvests a year. They said people could grow crops like sugar or tobacco easily. Detailed predictions in the Sketch promised millions of dollars in profits. Fish and game were so plentiful that a man could hunt or fish for one day and feed his family for a week. The native people were said to be helpful and very pro-British.

The capital city was St Joseph. It was described as a busy seaside town with wide paved streets, buildings with columns, and mansions. It supposedly had 20,000 people, a theater, an opera house, a domed cathedral, the Bank of Poyais, and a royal palace. There was even a mention of a planned Jewish colony. The Sketch even claimed that the rivers of Poyais contained "globules of pure gold."

Almost all of this was fiction. But MacGregor's idea that official-looking documents and printed words would convince many people was correct. The detailed information in the leather-bound Sketch, and the cost of printing it, helped to remove any doubts. Poyaisian land certificates cost two shillings and threepence per acre. This was about a working man's daily wage. Many saw it as a good investment. There was so much demand that MacGregor raised the price to two shillings and sixpence per acre in July 1822. Then he slowly raised it to four shillings per acre, and sales didn't drop. MacGregor said about 500 people had bought Poyaisian land by early 1823. These buyers included many who invested their life savings.

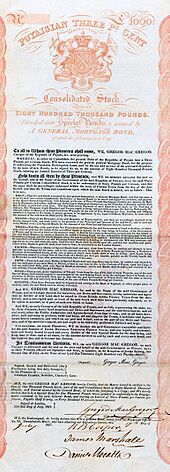

Besides selling land certificates, MacGregor spent several months organizing a Poyaisian government loan on the London Stock Exchange. Before this, he officially registered his 1820 land grant on October 14, 1822. Sir John Perring, Shaw, Barber & Co., a respected London bank, supported a £200,000 loan. This loan was backed by "all the revenues of the Government of Poyais," including land sales. They offered temporary certificates for the Poyaisian bonds on October 23. The bonds were for £100, £200, and £500. They were offered at a lower price of 80% of their value. The certificate could be bought for 15% of the price, with the rest due in two payments in January and February 1823. The interest rate was 6% per year. If the Poyaisian loan succeeded like those from Colombia, Peru, and Chile, MacGregor would become very rich.

Eager Settlers and Disappointment

MacGregor purposely targeted his fellow Scots as settlers. He thought they would be more likely to trust him since he was Scottish. Their emigration helped convince potential investors that Poyais was real and being developed. This would supposedly bring financial returns. This part of the scheme turned a clever hoax into a "cruel and deadly one." Some believe MacGregor "probably believed his own story" to some extent. He might have truly hoped to create a Poyaisian society with these people. MacGregor told his future colonists that he wanted Scots to populate Poyais. He said they had the strength and character needed to develop the new country. He mentioned the rivalry with England and the failed Darien scheme. He said that in Poyais, they could fix this historical wrong and restore Scottish pride.

Skilled workers were promised free passage to Poyais, supplies, and good government jobs. Hundreds, mostly Scots, signed up to move. Enough to fill seven ships. They included a London banker who was to lead the Bank of Poyais, doctors, civil servants, young men whose families bought them positions in the Poyaisian Army and Navy, and an Edinburgh shoemaker who became the Official Shoemaker to the Princess of Poyais.

The first group of emigrants was led by Hector Hall, a former British Army officer. He was made a lieutenant-colonel in the Poyaisian "2nd Native Regiment of Foot" and given the title "Baron Tinto" with a supposed 12,800-acre estate. Hall would sail with 70 emigrants on the Honduras Packet. MacGregor saw them off from London on September 10, 1822. He gave the banker, Mauger, 5,000 Bank of Poyais dollar notes. These were printed by the Bank of Scotland's official printer. The settlers were happy to exchange their gold for the "legal currency of Poyais." After MacGregor wished each settler good luck, he and Hall saluted each other. The Honduras Packet sailed, flying the Green Cross flag.

A second emigrant ship, the Kennersley Castle, was hired by MacGregor in October 1822. It left Leith, near Edinburgh, on January 22, 1823, with almost 200 emigrants. MacGregor again saw the settlers off. He came aboard to check on them. He announced that since this was the first emigrant trip from Scotland to Poyais, all women and children would travel for free. The Cazique was rowed back to shore to cheers from his colonists. The ship's captain fired a salute and raised the supposed flag of Poyais, then sailed out of port.

While claiming to be a royal Cazique, MacGregor tried to distance himself from the Latin American revolutionary movement. From late 1822, he quietly tried to work with the Spanish government regarding Central America. Spain paid little attention to him. The price of Poyaisian bonds remained steady until they were badly affected by other market events in November and December 1822. Amid problems in South America, the Colombian government suggested its London agent might have gone beyond his authority when he arranged a £2 million loan. When this agent suddenly died, the frantic buying of South American investments stopped. People started selling them quickly. MacGregor's money flow almost stopped when most people who bought the Poyaisian certificates didn't make their payments in January. While Colombian bonds recovered, Poyaisian ones never did. By late 1823, they were worth less than 10% of their original value.

The Honduras Packet reached the Black River in November 1822. The emigrants were confused to find a country very different from the Sketch descriptions. There was no sign of St Joseph. They set up camp on the shore, thinking the Poyaisian authorities would contact them soon. They sent many search parties inland. One, guided by natives who knew the name St Joseph, found some old foundations and rubble. Hall quickly realized MacGregor had tricked them. But he thought announcing this too soon would only cause panic. A few weeks after they arrived, the captain of the Honduras Packet suddenly sailed away during a storm. The emigrants were left alone, except for the natives and two American hermits. Hall tried to comfort the settlers, saying the Poyaisian government would find them if they stayed put. He then left for Cape Gracias a Dios, hoping to contact the Mosquito king or find another ship. Most emigrants found it hard to believe the Cazique had lied to them. They thought there must have been a terrible misunderstanding.

The second group of colonists arrived from the Kennersley Castle in late March 1823. Their hopes quickly disappeared. Hall returned in April with bad news. He had found no ship to help. King George Frederic Augustus had not even known they were there and didn't feel responsible for them. Since the Kennersley Castle had sailed away, MacGregor's victims had no help coming soon. The emigrants had brought plenty of supplies, including medicines, and had two doctors. So, they weren't completely without hope. But apart from Hall, none of the military officers or government officials MacGregor appointed tried to organize the group.

Hall returned to Cape Gracias a Dios several times for help. But he didn't explain his frequent absences to the settlers. This made the confusion and anger worse. Especially when he refused to pay the wages promised to those supposedly on Poyaisian government contracts. When the rainy season came, insects filled the camp. Diseases like malaria and yellow fever spread. The emigrants fell into deep despair. James Hastie, a Scottish sawyer who had brought his wife and three children, later wrote: "It seemed to be the will of Providence that every circumstance should combine for our destruction." Another settler, the would-be royal shoemaker, who had left a family in Edinburgh, died.

The ship Mexican Eagle, from British Honduras, found the settlers in early May 1823. It was carrying the Chief Magistrate of Belize, Marshal Bennet, to the Mosquito king's court. Seven men and three children had died, and many more were sick. Bennet told them that Poyais did not exist. He had never heard of this Cazique they spoke of. He advised them to return with him to British Honduras, as they would surely die if they stayed. Most preferred to wait for Hall to return, hoping for news of passage back to Britain. About half a week later, Hall returned with the Mosquito king. The king announced that MacGregor's land grant was immediately canceled. He said he had never given MacGregor the title of Cazique, or the right to sell land or raise loans. The emigrants were actually in George Frederic Augustus's territory illegally. They would have to leave unless they promised loyalty to him. All the settlers left except for about 40 who were too sick to travel.

The emigrants were transported on the crowded Mexican Eagle. They were in terrible shape when they reached Belize. Most had to be carried from the ship. The weather in British Honduras was even worse than at the Black River. The colony's authorities and doctors could do little to help the new arrivals. Disease spread quickly among the settlers, and most of them died. The colony's superintendent, Major-General Edward Codd, started an official investigation. He wanted to "lay open the true situation of the imaginary State of Poyais and... the unfortunate emigrants." He sent word to Britain about the Poyais settlers' fate. By the time the warning reached London, MacGregor had five more emigrant ships on the way. The Royal Navy stopped them. A third ship, the Skene, carrying 105 more Scottish emigrants, arrived at the Black River. But seeing the abandoned colony, the captain sailed on to Belize and dropped off his passengers there. The fourth and last ship to arrive was the Albion, which reached Belize in November 1823. But it was carrying supplies and not passengers. The cargo was sold locally.

The surviving colonists either settled in the United States, stayed in British Honduras, or sailed home on the Ocean, a British ship that left Belize on August 1, 1823. Some died during the journey back across the Atlantic. Of the roughly 250 people who had sailed on the Honduras Packet and Kennersley Castle, at least 180 had died. Fewer than 50 ever returned to Britain.

Poyais Scheme in France and Acquittal

MacGregor left London shortly before the small group of Poyais survivors arrived home on October 12, 1823. He told his friend Richardson that he was taking Josefa to Italy for her health. But he actually went to Paris. The London newspapers reported widely on the Poyais scandal in the following weeks and months. They highlighted the colonists' suffering and accused MacGregor of a huge trick. Six of the survivors, including Hastie, who had lost two children, claimed they were misquoted. On October 22, they signed a statement saying the blame was not MacGregor's, but Hall's and other members of the emigrant group. They said: "we believe that Sir Gregor MacGregor has been worse used by Colonel Hall and his other agents than was ever a man before... and that had they have done their duty by Sir Gregor and by us, things would have turned out very differently at Poyais." MacGregor claimed he himself had been tricked. He said some of his agents had stolen money. He also claimed that greedy merchants in British Honduras were purposely harming Poyais's development because it threatened their profits. Richardson tried to comfort the Poyais survivors. He strongly denied the newspaper claims that the country didn't exist. He also filed lawsuits against some British newspapers on MacGregor's behalf.

In Paris, MacGregor convinced a trading company called Compagnie de la Nouvelle Neustrie to find investors and settlers for Poyais in France. At the same time, he increased his efforts to contact King Ferdinand VII of Spain. In a November 1823 letter, the Cazique offered to make Poyais a Spanish protectorate. Four months later, he offered to lead a Spanish campaign to reconquer Guatemala, using Poyais as a base. Spain did nothing. One historian suggests MacGregor's "greatest pride" came in December 1824. In a letter to the King of Spain, he claimed to be "descendent of the ancient Kings of Scotland." Around this time, Josefa gave birth to their third and final child, Constantino, at their home in Paris.

Gustavus Butler Hippisley, a friend of Major Richardson and a veteran of the British Legions in Latin America, believed the Poyais story. He started working for MacGregor in March 1825. Hippisley wrote back to Britain, denying "the bare-faced calumnies of a hireling press." He especially criticized a journalist who called MacGregor a "penniless adventurer." With Hippisley's help, MacGregor negotiated with the Nouvelle Neustrie company. Its director was a Frenchman named Lehuby. They agreed to sell the French company up to 500,000 acres in Poyais for its own settlement plan. This was a clever way for MacGregor to distance himself. This time, he could honestly say others were responsible, and he had only made the land available.

Lehuby's company prepared a ship at Le Havre and began gathering French emigrants. About 30 of them got passports to travel to Poyais. MacGregor dropped the idea of working with Spain. He published a new Poyaisian constitution in Paris in August 1825. This time, he described Poyais as a republic, but he remained head of state with the title Cazique. On August 18, he raised a new £300,000 loan through an unknown London bank, offering 2.5% interest per year. There is no proof that these bonds were ever issued. The Sketch was shortened and republished as a 40-page booklet called Some Account of the Poyais Country.

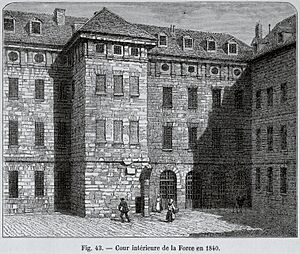

French government officials became suspicious when 30 more people asked for passports to this country they had never heard of. They ordered the Nouvelle Neustrie company's ship to stay in port. Some of the potential emigrants became worried and complained to the police. This led to the arrest of Hippisley and MacGregor's secretary Thomas Irving in Paris on September 4, 1825. Lehuby's ship never left Le Havre, and his colonists gradually went their separate ways.

MacGregor went into hiding in the French countryside, while Lehuby fled to the southern Netherlands. Hippisley and Irving were told on September 6 that they were being investigated for fraud and selling land titles they didn't own. Both said they were innocent. That evening, they were taken to La Force Prison.

MacGregor was arrested after three months and brought to La Force on December 7, 1825. He thought the charges were due to a sudden change in French policy or a Spanish plot to hurt Poyaisian independence. The three men remained in prison without trial while the French tried to get Lehuby from the Netherlands. MacGregor tried to link himself and Poyais to the Latin American revolutionary movement again. He issued a French statement from his prison cell on January 10, 1826. He claimed he was "held prisoner... for reasons of which he is not aware" and "suffering as one of the founders of independence in the New World." This attempt to claim diplomatic immunity didn't work. The French government and police ignored his statement.

The three Britons went to trial on April 6, 1826. Lehuby, still in the Netherlands, was tried without being present. The prosecution's case was severely weakened by his absence, especially since many key documents were with him. The prosecutor claimed a complex plot between MacGregor, Lehuby, and their helpers to profit from a fake land deal and loan. MacGregor's lawyer, Merilhou, argued that if anything wrong happened, the missing director should be blamed. He said there was no proof of a plot, and MacGregor might have been tricked by Lehuby himself. The prosecutor admitted there wasn't enough evidence to prove his case. He praised MacGregor for cooperating fairly and openly and dropped the charges. The three judges confirmed their release. But days later, the French authorities successfully got Lehuby from the Netherlands. The three men learned they would have to stand trial again.

The new trial, set for May 20, was delayed because the prosecutor said he wasn't ready. This delay gave MacGregor and Merilhou time to prepare a detailed, mostly fictional, 5,000-word statement. It described MacGregor's background, his actions in the Americas, and his complete innocence of any fraud. When the trial finally began on July 10, 1826, Merilhou was there not as MacGregor's lawyer, but as a witness for the prosecution. This was because of his connections with the Nouvelle Neustrie company.

Merilhou gave MacGregor's defense to a colleague named Berville. Berville read the entire 5,000-word statement to the court. Lehuby was found guilty of making false claims about selling shares and sentenced to 13 months in prison. But MacGregor was found not guilty on all charges. The accusations against Hippisley and Irving were removed from the record.

Return to Britain and Later Schemes

MacGregor quickly moved his family back to London. The uproar after the Poyais survivors returned had died down. During a serious economic downturn, some investors had bought into the £300,000 Poyais loan. They seemed to believe MacGregor's publicists who claimed previous loans failed only because one of his agents stole money. MacGregor was arrested soon after arriving back in Britain. He was held for about a week before being released without charges. He started a new, simpler version of the Poyais scheme. He simply called himself the "Cacique of the Republic of Poyais." The new Poyaisian office did not claim diplomatic status like the old one.

MacGregor convinced Thomas Jenkins & Company to help sell an £800,000 loan in mid-1827. It was for 20-year bonds at 3% interest. The bonds, valued at £250, £500, and £1,000, did not become popular. An anonymous flyer was passed around London. It described the previous Poyais loans and warned people to "Take Care of your Pockets—Another Poyais Humbug." The loan's poor performance forced MacGregor to sell most of the unsold certificates to a group of investors for a small amount of money. Historians say the Poyais bonds were seen as a "humbug" not because MacGregor's trick was fully exposed. It was simply because the previous investments had not made money. "Nobody thought to question the legitimacy of Poyais itself," one historian explains. "Some investors had begun to understand that they were being fleeced, but almost none realised how comprehensively."

Other versions of the Poyais scheme also failed. In 1828, MacGregor began selling certificates for "land in Poyais Proper" at five shillings per acre. Two years later, King Robert Charles Frederic, who became king in 1824, issued thousands of certificates for the same land. He offered them to lumber companies in London, directly competing with MacGregor. When the original investors demanded their overdue interest, MacGregor could only pay with more certificates. Other tricksters soon copied him. They set up their own "Poyaisian offices" in London, offering land in competition with both MacGregor and the Mosquito king. By 1834, MacGregor was back in Scotland, living in Edinburgh. He paid some unpaid investments by issuing yet another series of Poyaisian land certificates. Two years later, he published a constitution for a smaller Poyaisian republic. It was centered around the Black River region, and he was its president. However, it was clear that "Poyais had had its day." An attempt by MacGregor to sell some land certificates in 1837 is the last record of any Poyais scheme.

Return to Venezuela and Death

Josefa MacGregor died near Edinburgh on May 4, 1838. MacGregor almost immediately left for Venezuela. He settled in Caracas and in October 1838, he applied for citizenship and to get his old rank back in the Venezuelan Army. He also asked for back pay and a pension. He emphasized his struggles for Venezuela twenty years earlier. He claimed that Bolívar, who had died in 1830, had forced him to leave. He described several failed requests to return. He said he was "forced to remain outside the Republic... by causes and obstacles out of my control" while losing his wife, two children, and "the best years of my life and all my fortune."

The Defence Minister Rafael Urdaneta, who had served with MacGregor in 1816, asked the Senate to approve MacGregor's request. He said MacGregor had "enlisted in our ranks from the very start of the War of Independence, and ran the same risks as all the patriots of that disastrous time, meriting promotions and respect because of his excellent personal conduct." He called MacGregor's contributions "heroic with immense results." President José Antonio Páez, another former revolutionary comrade, approved the request in March 1839.

MacGregor was confirmed as a Venezuelan citizen and a divisional general in the Venezuelan Army. He received a pension of one-third of his salary. He settled in the capital and became a respected member of the local community. He died at home in Caracas on December 4, 1845. He was buried with full military honors in Caracas Cathedral. President Carlos Soublette, Cabinet ministers, and military chiefs marched behind his coffin. Obituaries in the Caracas newspapers praised General MacGregor's "heroic and triumphant retreat" to Barcelona in 1816. They described him as "a valiant champion of independence." There was no mention of Amelia Island, Porto Bello, or Rio de la Hacha, and no reference to the Cazique of Poyais. The part of today's Honduras that was supposedly called Poyais remains undeveloped in the 21st century. Back in Scotland, at the MacGregor graveyard near Loch Katrine, the clan memorial stones do not mention Gregor MacGregor or the country he invented.

|

See also

In Spanish: Gregor MacGregor para niños

In Spanish: Gregor MacGregor para niños

- British Legions British and Irish volunteer legions in the South American wars for independence

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |