History of Honduras facts for kids

Honduras was home to many different groups of native people when the Spanish arrived in the 1500s. The Lencas lived in the western and central parts. The Tol lived along the central north coast. The Pech (or Paya), Maya, and Sumo lived near Trujillo. These groups traded with each other and with people as far away as Panama and Mexico. Honduras has ancient city ruins from the pre-classic period, showing its long history before Europeans arrived.

The Spanish built new towns like Trujillo, Comayagua, Gracias, and Tegucigalpa. During the time of Spanish rule, people in Honduras focused on farming, mining for valuable metals, and raising animals. After Honduras became independent from Spain in 1821, it briefly joined the First Mexican Empire. When that empire ended in 1823, the Federal Republic of Central America was formed. This republic also ended in 1839, and Honduras became its own independent country.

Contents

- Ancient Times in Honduras

- Spanish Arrival and Conquest

- Honduras Under Spanish Rule

- Honduras in the 1800s

- Honduras in the 1800s (Continued)

- Honduras in the 1900s

- Honduras in the 2000s and 2010s

- See also

Ancient Times in Honduras

Archaeology shows that Honduras has a rich history with many different native groups. A very important part of this history is the Maya people. They lived around Copán in western Honduras, near the border with Guatemala. Copán was a major Mayan city that grew strong around 150 A.D. It was at its most powerful between 700 and 850 A.D. The Maya left behind many carved stones and tall stone monuments called stelae. The ancient kingdom of Copán, also called Xukpi or Oxwitik, existed from the 400s to the early 800s. Its history goes back even further, to at least the 100s.

Mayan culture spread across what are now the departments of Copán and Ocotepeque. It also reached many villages near these areas, especially by the Ulua River. Other Mayan archaeological sites in Honduras include El Puente. This was a smaller city that was independent for a while but worked closely with Copán. Rio Amarillo is another site. People believe it was a crossing point between valleys in Honduras and Guatemala. The Rastrojón site shows how the homes of the Mayan upper class were built.

The Mayan population began to shrink a lot in the 800s. However, people still lived in and around Copán until at least the 1200s. By the time the Spanish arrived in Honduras, the once-great city of Copán was covered by jungle. The remaining Ch’orti' people were separated from other groups who spoke their language. The non-Maya Lencas became powerful in western Honduras. They had many villages in the valleys. The Lenca were the largest and best-organized society in terms of military strength when the Spanish arrived in the early 1500s.

Many other areas also had large societies. Archaeological sites include Naco, La Sierra, and El Curruste in the northwest. These areas might have been home to people who spoke Western Jicaque. Los Naranjos is north of Lake Yojoa. Tenampúa and Yarumela are in the Comayagua valley. Some of these sites were built by the ancestors of the Lenca people. They were built almost 1000 years before the Mayan cities. These cities had complex buildings and were wealthy in the past. Their locations made them important trade centers, with access to both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. Items from Guatemala and central Mexico have been found there. Traces of products from other parts of South America also show that trade routes were used.

Honduras was part of Mesoamerica. It was home to complex, settled societies for thousands of years, just like nearby regions. It is clear that neighboring Maya societies and more distant Central Mexican societies greatly influenced Honduran communities. This happened through trade, especially with the Maya and the Olmec civilization. Sometimes, people also migrated. For example, during conflicts in the late Toltec Empire around 1000 to 1100 AD, Nahuatl-speaking people moved from Central Mexico. They spread into different parts of Central America, including Honduras.

Most large urban areas in Honduras were part of the Mesoamerican culture. However, La Ciudad Blanca is a major exception. It is on the edge of Mesoamerica and is better linked to the Isthmo-Colombian area. This civilization thrived from 500 A.D. to 1000 A.D. It had advanced ways of managing the environment and large urban centers. Even though it was outside the Mesoamerican area, studies show the city had Mayan features. These included a ball game and some pyramid-like structures, similar to those in western Honduras. Studies in the area show huge buildings in the city. One had a special area for ceremonies to kings and gods.

Spanish Arrival and Conquest

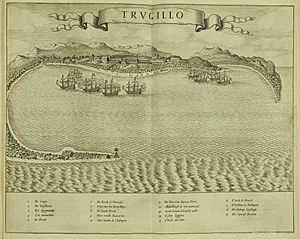

Europeans first saw Honduras when Christopher Columbus arrived at the Bay Islands on July 30, 1502. This was during his fourth voyage. On August 14, 1502, Columbus landed on the mainland near modern Trujillo. Columbus named the country Honduras, which means "depths," because of the deep waters off its coast.

In January 1524, Hernán Cortés sent Captain Cristóbal de Olid to start a colony in Honduras. It was called "Triunfo de la Cruz," which is now the town of Tela. Olid sailed with ships and over 400 soldiers and settlers to Cuba to get supplies. There, Governor Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar convinced him to claim the new colony for himself. Olid sailed to Honduras and landed east of Puerto Caballos at Triunfo de la Cruz. He settled there and declared himself governor.

Cortés heard about Olid's rebellion. He sent his cousin Francisco de las Casas with ships to Honduras to remove Olid and claim the area for Cortés. However, Las Casas lost most of his fleet in storms along the coast of Belize and Honduras. His ships barely made it into the bay at Triunfo, where Olid had his headquarters.

When Las Casas arrived, much of Olid's army was inland, dealing with another Spanish group. Olid decided to attack with two ships. Las Casas fought back and sent groups to capture Olid's ships. Olid then suggested a truce. Las Casas agreed and did not land his forces. During the night, a fierce storm destroyed Las Casas's fleet, and about a third of his men were lost. The rest were taken prisoner. After being forced to promise loyalty to Olid, they were released. But Las Casas was kept prisoner and was soon joined by González, who had also been captured by Olid's forces.

Spanish records tell two different stories about what happened next. One account says that Olid's soldiers rose up and killed him. Meanwhile, Cortés marched overland from Mexico to Honduras, arriving in 1525. Cortés ordered two cities to be founded: Nuestra Señora de la Navidad, near modern Puerto Cortés, and Trujillo. He named Las Casas governor. However, both Las Casas and Cortés sailed back to Mexico before the end of 1525.

On April 25, 1526, before returning to Mexico, Cortés named Hernando de Saavedra governor of Honduras. He told him to treat the native people well. On October 26, 1526, Diego López de Salcedo was appointed governor of Honduras by the emperor. The next ten years were filled with conflicts between the Spanish leaders. This made it hard to set up a good government. Spanish settlers rebelled against their leaders, and native people rebelled against the Spanish because of their harsh treatment.

Salcedo wanted to get rich. He clashed with Pedro Arias Dávila, governor of Castilla del Oro, who also wanted control of Honduras. In 1528, Salcedo arrested Pedrarias and forced him to give up some of his land in Honduras. But Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor did not approve this. After Salcedo died in 1530, the settlers gained more power. In this situation, the settlers asked Pedro de Alvarado to end the chaos. When Alvarado arrived in 1536, the disorder decreased, and the region came under his authority.

In 1537, Francisco de Montejo was appointed governor. He changed the land divisions Alvarado had made. One of Montejo's main captains, Alonso de Cáceres, put down a native revolt. This revolt was led by the chief Lempira in 1537 and 1538. In 1539, Alvarado and Montejo disagreed over who was governor. Montejo went to Chiapas, and Alvarado became governor of Honduras.

Before Pedro de Alvarado conquered Honduras, many native people along the north coast were captured. They were sent to work as prisoners on Spanish plantations in the Caribbean. This was part of the encomienda system. It was not until Alvarado defeated the native resistance led by Çocamba near Ticamaya in 1536 that the Spanish moved deeper into the country. Alvarado divided the native towns and gave their labor to the Spanish conquerors as repartimiento. More native uprisings happened near Gracias a Dios, Comayagua, and Olancho in 1537–38. The uprising near Gracias a Dios was led by Lempira. Today, the Honduran currency is named after him to honor him.

Honduras Under Spanish Rule

After Lempira's revolt was defeated and fighting among Spanish groups lessened, more settlements grew in Honduras. Economic activity also increased. By late 1540, Honduras seemed to be moving towards growth and wealth. This was helped by making Gracias the regional capital of the Audiencia of Guatemala in 1544.

However, this decision caused unhappiness in the more populated areas of Guatemala and El Salvador. In 1549, the capital was moved to Antigua, Guatemala. Honduras remained a new province within the Captaincy General of Guatemala until 1821.

Mining During Colonial Times

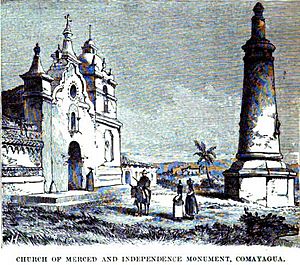

The first mining areas were near the Guatemalan border, around the city of Gracias in Lempira. In 1538, these mines produced a lot of gold for Spain. In the early 1540s, mining moved eastward to the Río Guayape Valley. Silver also became a major product, along with gold. This change led to the quick decline of Gracias and the rise of Comayagua as the main city in colonial Honduras.

The demand for forced labor also caused more revolts and quickly reduced the native population. African slavery was brought to Honduras. By 1545, the province might have had as many as 2,000 slaves. Other gold deposits were found near San Pedro Sula and the port of Trujillo.

Mining production started to decline in 1560, which made Honduras less important. In early 1569, new silver discoveries briefly boosted the economy. This led to the founding of Tegucigalpa, which soon became as important as Comayagua. The silver boom reached its peak in 1584, and then an economic downturn returned. Mining in Honduras faced problems like a lack of money and workers. The land was also difficult to work. Because the native population used for labor was shrinking, the Spanish decided to bring in slaves from Africa for the mines. Mercury, which was needed to produce silver, was hard to find in Honduras.

The Unconquered North Coast

While the Spanish conquered much of the south, they had less success on the Caribbean coast to the north. They founded towns like Puerto Caballos in the east. They sent minerals and other goods from the Pacific coast across the country to be shipped to Spain from Atlantic ports. They also founded inland towns in the northwest, such as Naco and San Pedro Sula.

In the northeast, the province of Tegucigalpa resisted all attempts to conquer it. This was true both physically in the 1500s and spiritually by missionaries in the 1600s and 1700s. Among the groups found along the Mosquito Coast were the Miskito. They were organized in a democratic and equal way, but they had a king. So, they were known as the Mosquito Kingdom.

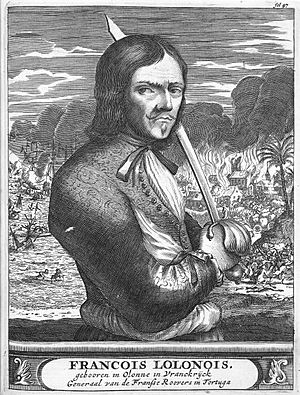

A big problem for the Spanish rulers of Honduras was the activity of the British in northern Honduras. The Spanish had only weak control over this region. These activities started in the 1500s and continued until the 1800s. In the early years, European pirates often attacked villages on the Honduran Caribbean coast. The Providence Island Company, which was on Providence Island near the coast, sometimes raided Honduras. They also had settlements on the shore, around Cape Gracias a Dios. Around 1638, the Miskito king visited England and made an alliance with the English crown. In 1643, an English group destroyed the city of Trujillo, which was Honduras's main port.

The British and the Miskito Kingdom

The Spanish sent a fleet from Cartagena that destroyed the English colony at Providence Island in 1641. For a time, the English base near the shore was gone. Around the same time, a group of slaves rebelled and captured the ship they were on. It then crashed at Cape Gracias a Dios. They managed to get ashore and were welcomed by the Miskito people. Within a generation, this led to the Miskito Zambo, a mixed-race group that became the leaders of the kingdom by 1715.

Meanwhile, the English captured Jamaica in 1655. They soon looked for allies on the coast and found the Miskito. Their king, Jeremy I, visited Jamaica in 1687. Many other Europeans settled in the area during this time. A report from 1699 shows a mix of private individuals, large Miskito family groups, Spanish settlements, and pirate hideouts along the coast.

Britain declared much of the area a British protectorate in 1740. However, they had little real power there. British settlement was especially strong in the Bay Islands. Alliances between the British and Miskito people, as well as local supporters, made this an area the Spanish could not easily control. It also became a safe place for pirates.

Bourbon Reforms

In the early 1700s, the House of Bourbon, related to the rulers of France, took over the throne of Spain from the Habsburgs. The new royal family started a series of changes across the empire, called the Bourbon Reforms. These changes aimed to make the government more efficient and profitable. They also wanted to make it easier to defend the colonies. One of these changes was lowering taxes on precious metals and the price of mercury, which was controlled by the king. In Honduras, these reforms helped the mining industry grow again in the 1730s.

Under the Bourbons, the Spanish government tried several times to regain control of the Caribbean coast. In 1752, the Spanish built the fort of San Fernando de Omoa. In 1780, the Spanish returned to Trujillo. This city became a base for operations against British settlements to the east. During the 1780s, the Spanish regained control of the Bay Islands. They also captured most of the British and their allies in the Black River area. However, they could not expand their control beyond Puerto Caballos and Trujillo. This was because of strong Miskito resistance. The Anglo-Spanish Convention of 1786 finally recognized Spanish control over the Caribbean coast.

Honduras in the 1800s

Independence from Spain (1821)

In the early 1800s, Napoleon's control of Russia led to revolts across Spanish America. In New Spain, the fight for independence happened mainly in central Mexico from 1810 to 1821. Once the Viceroy was defeated in Mexico City in 1821, news of independence spread to all parts of New Spain. This included the areas that were once the Captaincy of Guatemala. Honduras, accepting this news, joined the other Central American areas in declaring independence from Spain. This public announcement was made through the Act of Independence of Central America in 1821.

After declaring independence, the New Spain parliament wanted to create a commonwealth. In this plan, the King of Spain, Ferdinand VII, would also be Emperor of New Spain. Both countries would have their own laws and legislative offices. If the king refused, a member of the House of Bourbon would take the New Spain throne. However, Ferdinand VII did not recognize the independence. He said Spain would not allow any other European prince to take the throne of New Spain.

At the request of Parliament, Agustín de Iturbide, the president of the regency, was declared emperor of New Spain. But Parliament also decided to rename New Spain to Mexico. The First Mexican Empire was the official name for this monarchy from 1821 to 1823. The Mexican Empire included the continental areas and provinces of New Spain, including those from the former Captaincy General of Guatemala.

Federal Independence Period (1821–1838)

In 1823, a revolution in Mexico removed Emperor Agustín de Iturbide. A new Mexican congress voted to let the Central American areas decide their own future. That year, the United Provinces of Central America was formed. It included the five Central American areas: Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. General Manuel José Arce led this new union. The areas took on the new name of "states."

Important figures from this federal time include Dionisio de Herrera, Honduras's first democratically elected president. He was a lawyer whose government, starting in 1824, created the first constitution. After him came the presidency of General Francisco Morazán. He was Federal President from 1830–1834 and 1835–1839. Morazán represented the ideal of Central American unity. Another key figure was José Cecilio del Valle, who wrote the Declaration of Independence signed in Guatemala on September 15, 1821. He was also Mexico's Foreign Minister in 1823.

Soon, social and economic differences between Honduras's social classes and its neighbors caused harsh political fights among Central American leaders. This led to the collapse of the Federation from 1838 to 1839. General Morazán tried many times to keep the federation together during the First Central American Civil War. He fought against conservatives who saw his policies, like making the federation a secular state (not controlled by religion), as a threat. However, despite Morazán's victories, his army became tired from the war. The situation became very difficult until he was captured and shot in Costa Rica. His legacy was so important in Honduras and Central America that the department of Francisco Morazan was named after him. Several statues were put up in his honor in the late 1800s. Restoring Central American unity remained the main goal of Honduran foreign policy until after World War I. Honduras left the Central American Federation in October 1838 and became an independent and sovereign state.

Honduras in the 1800s (Continued)

In the 1840s and 1850s, Honduras took part in several failed attempts to bring Central America back together. These included the Confederation of Central America (1842–1845) and other meetings. All of these attempts were stopped by conservatives in all Central American countries.

Even though Honduras eventually became the Republic of Honduras, the idea of unity never faded. Honduras was one of the Central American countries that pushed hardest for regional unity.

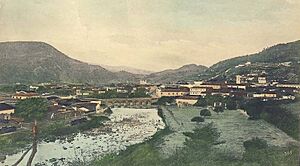

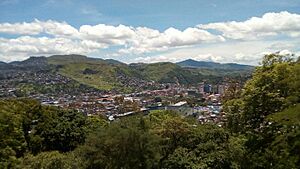

In 1850, Honduras tried to build an Inter-Oceanic Railroad with foreign help. It was planned to go from Trujillo to Tegucigalpa and then to the Pacific Coast. The project stopped because of difficulties, corruption, and other problems. In 1888, it ran out of money when it reached San Pedro Sula. This led to San Pedro Sula growing into the nation's main industrial center and second-largest city. Since independence, nearly 300 small internal rebellions and civil wars have happened in the country. Comayagua was the capital of Honduras until 1880, when it was moved to Tegucigalpa.

Honduras in the 1900s

The North Coast and Foreign Influence (1899–1932)

Both political stability and instability helped and hindered the economic changes in Honduras. These changes came from developing a plantation economy on the north coast. As American companies bought more and more land in Honduras, they asked the US government to protect their investments. Conflicts over land, farmers' rights, and a US-friendly group of rich Hondurans led to armed fights. The US military invaded Honduras many times: in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924, and 1925. Because American fruit companies largely controlled the country, Honduras was the original inspiration for the term "banana republic".

The Rise of US Influence (1899–1919)

In 1899, the banana industry in Honduras was growing fast. For the first time in decades, power was transferred peacefully from Policarpo Bonilla to General Terencio Sierra. By 1902, railroads had been built along the Caribbean coast to help the growing banana industry. However, Sierra tried to stay in office and refused to step down after a new president was elected in 1902. He was then overthrown by Manuel Bonilla in 1903.

After removing Sierra, Manuel Bonilla, a conservative, put his liberal rival, ex-president Policarpo Bonilla, in prison for two years. He also tried to stop liberals across the country, as they were the only other organized political party. The conservatives were split into many groups and lacked strong leadership. But Bonilla reorganized the conservatives into a "national party." Today's National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras—PNH) traces its beginnings to his time in office.

Bonilla proved to be even more helpful to the banana companies than Sierra. Under Bonilla's rule, companies received tax breaks and permission to build docks and roads. They also got permission to improve waterways and build new railroads. He also successfully set the border with Nicaragua and fought off an invasion from Guatemala in 1906. After fighting off Guatemalan forces, Bonilla sought peace and signed a friendship agreement with both Guatemala and El Salvador.

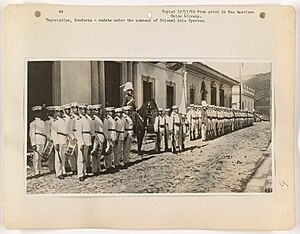

Nicaragua's president José Santos Zelaya saw this friendship agreement as an alliance against Nicaragua. He began to try and weaken Bonilla. Zelaya supported liberal Honduran exiles in Nicaragua who wanted to overthrow Bonilla, who had become a dictator. With help from parts of the Nicaraguan army, the exiles invaded Honduras in February 1907. Manuel Bonilla, with help from Salvadoran troops, tried to resist. But in March, his forces were badly defeated in a battle known for being the first time machine guns were used in Central America. After overthrowing Bonilla, the exiles set up a temporary government, but it did not last.

American leaders noticed this. It was in their interest to stop Zelaya, protect the area around the new Panama Canal, and defend the increasingly important banana trade. This invasion by Honduran exiles, helped by Nicaragua, greatly upset the United States government. The US believed Zelaya wanted to control all of Central America. They sent marines to Puerto Cortes to protect the banana trade. US naval ships were also sent to Honduras and successfully defended Bonilla's last position at Amapala in the Gulf of Fonseca. Through a peace agreement arranged by the US representative in Tegucigalpa, Bonilla stepped down, and the war with Nicaragua ended.

The agreement also set up a compromise government led by General Miguel R. Davila in Tegucigalpa. However, Zelaya was not happy with the agreement, as he deeply distrusted Davila. Zelaya made a secret plan with El Salvador to remove Davila from office. The plan failed, but it worried American businesses in Honduras. Mexico and the U.S. called the five Central American countries to diplomatic talks at the Central American Peace Conference to make the area more stable. At the conference, the five countries signed the General Treaty of Peace and Amity of 1907. This treaty created the Central American Court of Justice to solve future disagreements among the five nations. Honduras also agreed to stay neutral in any future conflicts between the other nations.

In 1908, Davila's opponents tried and failed to overthrow him. Despite this failure, American leaders became worried about Honduras's instability. The Taft Administration saw Honduras's huge debt, over $120 million, as a reason for the instability. They began efforts to repay the mostly British debt. This would involve the United States controlling customs revenue or a similar arrangement. Negotiations were set up between Honduran representatives and New York bankers, led by J.P. Morgan. By the end of 1909, an agreement was reached. It would reduce the debt and issue new 5% bonds. The bankers would control the Honduran railroad, and the United States government would guarantee Honduras's continued independence. It would also take control of customs revenue.

The terms proposed by the bankers faced a lot of opposition in Honduras. This further weakened the Dávila government. A treaty with the main parts of this agreement with J.P. Morgan was finally signed in January 1911. Dávila submitted it to the Honduran legislature. However, that group, in a rare show of independence, rejected it by a vote of thirty-three to five.

An uprising in 1911 against Dávila stopped efforts to deal with the debt problem. The United States Marines landed, which forced both sides to meet on a US warship. The revolutionaries, led by former president Manuel Bonilla, and the government agreed to stop fighting. They also agreed to install a temporary president chosen by the United States mediator, Thomas Dawson. Dawson chose Francisco Bertrand, who promised to hold early, free elections. Dávila resigned.

The 1912 elections were won by Manuel Bonilla, but he died after just over a year in office. Bertrand, who had been his vice president, returned to the presidency. In 1916, he won election for a term that lasted until 1920. Between 1911 and 1920, Honduras had relative stability. Railroads expanded throughout Honduras, and the banana trade grew quickly. However, this stability would be hard to keep after 1920. Revolutionary plots also continued, along with constant rumors that one group or another was being supported by a banana company.

The growth of the banana industry led to the start of organized labor movements in Honduras. It also caused the first major strikes in the nation's history. The first strike happened in 1917 against the Cuyamel Fruit Company. The Honduran military stopped the strike. But the next year, more labor problems occurred at the Standard Fruit Company in La Ceiba. In 1920, a general strike hit the Caribbean coast. In response, a United States warship was sent to the area, and the Honduran government began arresting leaders. When Standard Fruit offered a new wage of US$1.75 per day, the strike eventually ended. However, labor problems in the banana trade were far from over.

The Fruit Companies' Activities

The Liberal government decided to increase mining and farming. In 1876, it started giving large land grants and tax breaks to foreign companies and local businesses. Mining was very important. The new policies also matched the growth of banana exports. This began in the Bay Islands in the 1870s and was done on the mainland by small and medium farmers in the 1880s. Liberal concessions allowed US-based companies to enter the Honduran market. First, they were shipping companies, then railroad and banana producing businesses.

The US companies created very large plantations. Workers came from the crowded Pacific coast, other Central American countries, and the English-speaking Caribbean. The companies often preferred West Indian workers because they spoke English and were sometimes better educated than Honduran workers. This feeling of foreign control, along with growing prejudice against African-descended West Indians, caused a lot of tension. The arrival of West Indians changed the population in the region.

The link between the wealth from the banana trade and the influence of outsiders, especially North Americans, led O. Henry, an American writer, to create the term "banana republic". He used it to describe a fictional nation based on Honduras. By 1912, three companies controlled the banana trade in Honduras: Samuel Zemurray's Cuyamel Fruit Company, Vaccaro Brothers and Company, and the United Fruit Company. These companies often owned their own lands, railroad companies, and ship lines. Through land given to the railroads, they soon controlled huge areas of the best land along the Caribbean coast. Coastal cities like La Ceiba, Tela, and Trujillo, and inland towns like El Progreso and La Lima, became almost like company towns.

For the next twenty years, the US government was involved in calming Central American disputes, uprisings, and revolutions. These were sometimes supported by neighboring governments or by US companies. As part of the so-called Banana Wars around the Caribbean, Honduras saw American troops arrive in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1924, and 1925. For example, in 1917, the Cuyamel Fruit Company extended its rail lines into disputed Guatemalan territory.

New Instability (1919–1924)

In 1919, it became clear that Francisco Bertrand would not allow a fair election for his replacement. The United States opposed this, and it had little public support in Honduras. The local military commander and governor of Tegucigalpa, General Rafael López Gutiérrez, led the opposition against Bertrand. López Gutiérrez also asked for support from Guatemala and Nicaragua. Bertrand, in turn, sought help from El Salvador.

The United States government wanted to avoid an international conflict. After some thought, it offered to help settle the dispute. It hinted to the Honduran president that if he refused, direct intervention might follow. The United States landed US Marines on September 11, 1919. Bertrand quickly resigned and left the country. The United States ambassador helped set up a temporary government led by Francisco Bográn, who promised to hold free elections. General López Gutiérrez, who now controlled the military, made it clear he wanted to be the next president. After much discussion, elections were held. López Gutiérrez won easily in a manipulated election, and in October 1920, he became president.

During Bográn's short time in office, he agreed to a US proposal to invite a US financial adviser to Honduras. Arthur N. Young from the Department of State was chosen. He worked in Honduras from August 1920 to August 1921. While there, Young gathered a lot of information and made many suggestions. He even convinced the Hondurans to hire a New York police lieutenant to reorganize their police force. Young's investigations clearly showed that Honduras desperately needed major financial reforms. The country's already shaky budget was made much worse by new revolutionary activities.

For example, in 1919, the military spent more than double its budget. This accounted for over 57 percent of all government spending. Young's suggestions for reducing the military budget were not popular with the new López Gutiérrez government. The government's financial situation remained a big problem. The goal was to modernize the Honduran army, which still used old technology from the late 1800s. If anything, continued uprisings against the government and the threat of a new Central American conflict made the situation even worse. From 1919 to 1924, the Honduran government spent US$7.2 million more than its regular budget on military operations.

Coups

From 1920 to 1923, seventeen uprisings or attempted coups in Honduras worried the United States about political instability in Central America. In August 1922, the presidents of Honduras, Nicaragua, and El Salvador met on the USS Tacoma in the Gulf of Fonseca. With US ambassadors watching, the presidents promised to prevent their lands from being used to start revolutions against their neighbors. They also called for a meeting of Central American states in Washington at the end of the year.

The Washington conference ended in February with the General Treaty of Peace and Amity of 1923. This treaty had eleven extra agreements. The treaty largely followed the rules of the 1907 treaty. The Central American court was reorganized, reducing the governments' influence over its members. The rule about not recognizing revolutionary governments was expanded. It now prevented recognition of any revolutionary leader, their relatives, or anyone who had been in power six months before or after such an uprising. This was unless their claim to power was confirmed by free elections. The governments promised again not to help revolutionary movements against their neighbors. They also promised to find peaceful solutions for all disagreements.

The extra agreements covered everything from promoting farming to limiting weapons. One agreement, which was not approved, allowed for free trade among all states except Costa Rica. The arms limitation agreement set a limit on the size of each nation's military forces (2,500 men for Honduras). It also included a US-supported promise to seek foreign help to create more professional armed forces.

The Honduran presidential elections in October 1923 and the conflicts that followed were the first real tests of these new treaty rules. Under strong pressure from Washington, López Gutiérrez allowed a very open campaign and election. The conservatives, who had been split for a long time, reunited as the National Party of Honduras (Partido Nacional de Honduras—PNH). Their candidate was General Tiburcio Carías Andino, the governor of Cortés.

The liberal PLH could not agree on one candidate and split into two groups. One supported former president Policarpo Bonilla, and the other supported Juan Angel Arias. As a result, no candidate won a majority. Carías received the most votes, with Bonilla second and Arias a distant third. According to the Honduran constitution, this meant the legislature had to choose the president. But that group could not get enough members to meet and make a decision. In January 1924, López Gutiérrez announced he would stay in office until new elections could be held. But he kept refusing to set a date. Carías, reportedly with support from United Fruit, declared himself president, and an armed conflict began. In February, the United States warned that it would not recognize anyone who came to power by revolution. It then stopped relations with the López Gutiérrez government for not holding elections.

Conditions quickly worsened in early 1924. On February 28, a fierce battle happened in La Ceiba between government troops and rebels. Even with the USS Denver present and US Marines landing, widespread looting and fires could not be stopped. This caused over US$2 million in property damage. Fifty people, including a US citizen, were killed in the fighting. In the following weeks, more ships from the United States Navy were sent to Honduran waters. Landing parties went ashore to protect US interests. A group of marines and sailors was sent inland to Tegucigalpa to further protect the US embassy. Shortly before they arrived, López Gutiérrez died. What little authority the central government had was then held by his cabinet. General Carías and other rebel leaders controlled most of the countryside. But they failed to work together well enough to capture the capital.

To end the fighting, the United States government sent Sumner Welles to the port of Amapala. He was told to try and create an agreement that would bring a government to power that the US could recognize under the 1923 treaty. Negotiations, again held on a US cruiser, lasted from April 23 to 28. An agreement was reached that set up a temporary presidency led by General Vicente Tosta. He agreed to appoint a cabinet with members from all political groups. He also promised to call a Constituent Assembly within ninety days to restore constitutional order. Presidential elections were to be held as soon as possible, and Tosta promised not to run himself. Once in office, the new president showed signs of not keeping some of his promises, especially about a cabinet with members from all parties. However, under strong pressure from the United States delegation, he eventually followed the peace agreement.

Keeping the 1924 elections on track was hard. To pressure Tosta to hold a fair election, the United States continued to stop arms from reaching Honduras. It also prevented the government from getting loans, including a requested US$75,000 from the Banco Atlántida. Also, the United States convinced El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua to agree that, under the 1923 treaty, no leader of the recent revolution would be recognized as president for the next term. These pressures eventually helped convince Carías to withdraw his candidacy. They also helped ensure the defeat of an uprising led by General Gregorio Ferrera of the PNH. The PNH nominated Miguel Paz Barahona (1925–29), a civilian, for president. The PLH, after some debate, refused to nominate a candidate. On December 28, Paz Barahona won the election with almost all the votes.

Order Restored (1925–1931)

Despite another small uprising led by General Ferrera in 1925, Paz Barahona's time as president was quite peaceful for Honduras. The banana companies kept growing, the government's budget improved, and there was even more labor organizing. On the international side, the Honduran government, after years of talks, finally made a deal with British bondholders to pay off most of its huge national debt. The bonds would be paid back at 20 percent of their original value over thirty years. Old interest was forgiven, and new interest only started in the last fifteen years of this deal. With this agreement, Honduras finally seemed to be on its way to being financially stable.

Fears of problems grew again in 1928 as the presidential elections approached. The ruling PNH nominated General Carías. The PLH, united again after Policarpo Bonilla's death in 1926, nominated Vicente Mejía Colindres. To most people's surprise, both the campaign and the election were held with very little violence or threats. Mejía Colindres won a clear victory, getting 62,000 votes compared to 47,000 for Carías. Even more surprising was Carías's public acceptance of his defeat. He urged his supporters to accept the new government.

Mejía Colindres became president in 1929 with high hopes for his government and his country. Honduras seemed to be moving towards political and economic progress. Banana exports, which made up 80 percent of all exports, continued to grow. By 1930, Honduras had become the world's top producer of bananas. It supplied one-third of the world's bananas. United Fruit increasingly controlled the trade. In 1929, it bought out the Cuyamel Fruit Company, one of its main rivals. Conflicts between these companies had often led to support for rival groups in Honduran politics. They had also caused border disputes with Guatemala and may have even contributed to revolutionary unrest. This merger seemed to promise more peace at home. The chance for peace was further improved in 1931 when Ferrera and his rebels were killed. This happened during one last failed attempt to overthrow the government after troops found their hiding place.

Many of Mejía Colindres's hopes were ruined by the start of the Great Depression. Banana exports peaked in 1930, then quickly dropped. Thousands of workers lost their jobs. The wages of those who kept their jobs were cut. The prices paid to independent banana producers by the giant fruit companies were also reduced. Strikes and other labor problems began to happen because of these conditions. But most were quickly stopped with the help of government troops. As the depression got worse, the government's financial situation got worse too. In 1931, Mejía Colindres had to borrow US$250,000 from the fruit companies to make sure the army would still be paid.

Tiburcio Carías Andino (1932–1949)

Despite growing unrest and serious economic problems, the 1932 presidential elections in Honduras were fairly peaceful and honest. The peaceful transition of power was surprising. This was because the start of the depression had led to governments being overthrown elsewhere in Latin America, even in countries with stronger democratic traditions than Honduras. After United Fruit bought Cuyamel, Sam Zemurray, a strong supporter of the Liberal Party, left the country. The Liberals were short on money by the 1932 election. However, Mejía Colindres resisted pressure from his own party to change the results to favor the PLH candidate, Angel Zúñiga Huete. As a result, the PNH candidate, Carías, won the election by about 20,000 votes. On November 16, 1932, Carías took office. This began the longest continuous period in power for any single person in Honduran history.

Shortly before Carías became president, some liberal opponents had revolted, even though Mejía Colindres was against it. Carías took command of the government forces, got weapons from El Salvador, and quickly crushed the uprising. Most of Carías's first term was spent trying to avoid financial collapse. He also worked to improve the military, build some roads, and set the stage for staying in power longer.

The economy remained very bad throughout the 1930s. Besides the big drop in banana exports due to the depression, the fruit industry was also threatened. In 1935, diseases like Panama disease (a fungus) and sigatoka (leaf blight) broke out in the banana-growing areas. Within a year, most of the country's banana production was at risk. Large areas, including most around Trujillo, were abandoned. Thousands of Hondurans lost their jobs. By 1937, a way to control the disease was found. But many affected areas remained out of production because a large part of the market Honduras once had shifted to other nations.

Carías had worked to improve the military even before he became president. Once in office, his ability and desire to continue and expand these improvements grew. He paid special attention to the new air force. He founded the Military Aviation School in 1934 and arranged for a United States colonel to lead it.

As months passed, Carías slowly but steadily strengthened his control. He gained the support of the banana companies by opposing strikes and other labor problems. He strengthened his position with Honduran and foreign financial groups through careful economic policies. Even during the worst of the depression, he continued to make regular payments on Honduras's debt. He strictly followed the agreement with the British bondholders and also satisfied other creditors. Two small loans were fully paid off in 1935.

Political controls were put in place slowly under Carías. The Communist Party of Honduras (Partido Comunista de Honduras—PCH) was banned. But the PLH continued to operate. Even the leaders of a small uprising in 1935 were later offered free air travel if they wanted to return to Honduras from exile. However, at the end of 1935, Carías began to crack down on opposition newspapers and political activities. He stressed the need for peace and order. Meanwhile, the PNH, following the president's orders, started a campaign saying that only keeping Carías in office could give the nation continued peace and order. However, the constitution did not allow presidents to be reelected right away.

To extend his time in office, Carías called a special assembly to write a new constitution. This assembly would also choose the person to serve the first presidential term under that new document. Besides the president wanting to stay in office, there seemed little reason to change the nation's basic rules. Earlier assemblies had written thirteen constitutions (only ten of which became law), and the latest had been adopted in 1924. The chosen Constituent Assembly of 1936 included thirty articles from the 1924 document in the 1936 constitution.

The main changes were removing the ban on a president and vice president being reelected right away. They also made the presidential term longer, from four years to six. Other changes included bringing back the death penalty, reducing the power of the legislature, and taking away citizenship from women, which also meant they could not vote. Finally, the new constitution included a rule saying that the current president and vice president would stay in office until 1943. But Carías, who was almost a dictator by then, wanted even more. So, in 1939, the legislature, which was completely controlled by the PNH, extended his term by another six years (to 1949).

The PLH and other opponents of the government reacted to these changes by trying to overthrow Carías. Many coup attempts in 1936 and 1937 only made the PNH's opponents weaker. By the end of the 1930s, the PNH was the only organized political party in the nation. Many opposition leaders had been imprisoned. Some were reportedly chained and made to work in the streets of Tegucigalpa. Others, including the PLH leader Zúñiga Huete, had fled into exile.

During his presidency, Carías built close relationships with other Central American dictators. These included generals Jorge Ubico in Guatemala, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez in El Salvador, and Anastasio Somoza García in Nicaragua. Relations were especially close with Ubico. He helped Carías reorganize his secret police. Ubico also captured and shot the leader of a Honduran uprising who had crossed into Guatemalan territory by mistake. Relations with Nicaragua were a bit more tense because of a continuing border dispute. But Carías and Somoza managed to keep this dispute under control throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

The value of these ties became questionable in 1944. Popular revolts in Guatemala and El Salvador removed Ubico and Hernández Martínez from power. For a time, it seemed like the revolutionary feeling might spread to Honduras too. A plot, involving some military officers and civilian opponents, had already been found and stopped in late 1943. In May 1944, a group of women started protesting outside the Presidential Palace in Tegucigalpa. They demanded the release of political prisoners.

Despite strong government actions, tension continued to grow. Carías was eventually forced to release some prisoners. This action did not satisfy the opposition, and anti-government protests continued to spread. In July, several protesters were killed by troops in San Pedro Sula. In October, a group of exiles invaded Honduras from El Salvador. But they failed to overthrow the government. The military remained loyal, and Carías stayed in office.

World War II

Honduras had diplomatic relations with countries that were part of the Axis powers until 1941. It declared war on the Empire of Japan on December 8, 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Then, it declared war on Nazi Germany and the Kingdom of Italy on December 12 of the same year. Several Honduran merchant ships were sunk in the Caribbean by German submarines. These submarines had already been seen in the Gulf of Fonseca and the Caratasca lagoon. Because of this, air patrols began in 1942.

This was possible thanks to the modernization of the Honduran army and the creation of the Honduran Air Force. The aircraft used for these patrols were the North American NA-16, Chance Vought F4U Corsair, and the Boeing Model 40 and Model 95 modified to drop bombs. The first time the air force saw a German U-boat was on July 24, 1942. It was attacked by planes with 60-pound bombs. This is possibly the only official record of a military fight between Honduras and Nazi Germany. Many raw materials produced in Honduras were sent to the United States. These supplies helped soldiers in the Pacific War against the Japanese, in the North African theater, and later in the European theater in 1944 after the D-Day landing.

End of Carías's Rule

The United States wanted to stop further disorder in the region. It began to urge Carías to step aside and allow free elections when his term ended. Carías, who was in his early seventies, eventually agreed. He announced elections for October 1948, in which he would not run. However, he still found ways to use his power. The PNH nominated Carías's choice for president, Juan Manuel Gálvez, who had been minister of war since 1933. Exiled opposition figures were allowed to return to Honduras. The PLH, trying to recover from years of inactivity and division, nominated Zúñiga Huete, the same person Carías had defeated in 1932. The PLH quickly realized it had no chance to win. Charging the government with unfair election practices, it boycotted the elections. This gave Gálvez a victory with almost no opposition. In January 1949, he became president.

It is hard to judge Carías's presidency. His time in office gave the nation a much-needed period of relative peace and order. The country's financial situation steadily improved. Education got a little better, the road network expanded, and the armed forces were modernized. At the same time, new democratic institutions weakened. Opposition and labor activities were stopped. National interests were sometimes sacrificed to benefit Carías's supporters and relatives or major foreign companies.

New Reforms (1949–1954)

Once in office, Gálvez showed more independence than expected. He continued and expanded some of Carías's policies. These included building roads and developing coffee exports. By 1953, almost a quarter of the government budget was spent on road construction. Gálvez also continued most of the previous government's financial policies. He reduced foreign debt and paid off the last of the British bonds. The fruit companies continued to receive good treatment from the Gálvez government. For example, United Fruit received a very favorable twenty-five-year contract in 1949.

However, Gálvez did introduce some important new things. Education received more attention and a larger share of the national budget. Congress passed an income tax law, although it was not always enforced well. A good amount of press freedom was brought back. The PLH and other groups were allowed to organize, and some worker organizations were permitted. Workers also benefited from new laws during this time. Congress passed, and the president signed, laws that set an eight-hour workday. They also created paid holidays for workers, limited employer responsibility for work-related injuries, and set rules for employing women and children.

Mid-1900s (1955–1979)

After a big strike in 1954, young military reformers took power in October 1955. They set up a temporary government. Capital punishment (the death penalty) was ended in 1956, though Honduras had not had an execution since 1940. Elections for a special assembly in 1957 chose Ramón Villeda as president. This assembly then became the national Congress with a 6-year term. The Liberal Party of Honduras (PLH) was in power from 1957–63. The military started to become a professional group separate from politics. Its new military academy had its first graduating class in 1960.

In October 1963, conservative military officers stopped the planned elections. They removed Ramón Villeda Morales in a bloody coup. These officers sent PLH members into exile and governed under General Oswaldo López until 1970. In July 1969, El Salvador invaded Honduras in the short Football War. Tensions from this conflict remained.

A civilian president for the PNH, Ramón Ernesto Cruz, briefly took power in 1970. But in December 1972, López staged another coup. This time, he adopted more progressive policies, including land reform (changing how land is owned and distributed).

López's successors continued to modernize the armed forces. They built up the army and security forces, focusing on making the Honduran air force stronger than its neighbors'. During the governments of General Juan Alberto Melgar Castro (1975–78) and General Policarpo Paz García (1978–82), Honduras built most of its physical infrastructure. This included electricity and telephone systems, both controlled by the state. The country's economy grew during this time. There was more international demand for its products and more foreign money available.

Constituent Assembly (1980)

In 1982, Honduras returned to civilian rule. A special assembly was elected by the people in April 1980. General elections were held in November 1981. A new constitution was approved in 1982. The PLH government of Roberto Suazo took power.

The 1980s

Roberto Suazo Córdova won the elections with a big plan for economic and social development. He wanted to fix the country's economic problems. During this time, Honduras also helped the contra guerrillas.

President Suazo started ambitious social and economic development projects. These were supported by American aid. Honduras became home to the largest Peace Corps mission in the world. Many non-government and international volunteer groups grew.

From 1972 to 1983, military groups governed Honduras.

Although Honduras avoided the bloody civil wars in neighboring countries, the Honduran army quietly fought against Marxist rebels. These included the Cinchoneros Popular Liberation Movement, known for kidnappings and bombings. The army's actions also involved killings by government units, especially the CIA-trained Battalion 3-16.

Many trade union members, teachers, farmers, and students disappeared. Secret documents show that US Ambassador John Negroponte personally stopped information about these crimes from being revealed. This was to avoid "creating human rights problems in Honduras." The US kept a military presence in Honduras. This was to support the Contra guerrillas fighting the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. It also supported the fight against leftist guerrillas in El Salvador and Guatemala. They also built an airstrip and a modern port in Honduras. US military aid to Honduras increased from $4 million in 1981 to $77.4 million in 1984.

President Suazo, with US support, created big social and economic development projects. These aimed to help with a serious economic downturn and the perceived threat of regional instability. As the November 1985 election neared, the PLH could not agree on a presidential candidate. They interpreted election law as allowing multiple candidates from one party. The PLH claimed victory when its presidential candidates together got more votes than the PNH candidate, Rafael Leonardo Callejas. He received 42% of the total vote. José Azcona, the candidate with the most votes (27%) among the PLH, became president in January 1986. With strong backing from the Honduran military, the Suazo government brought about the first peaceful transfer of power between civilian presidents in over 30 years. In 1989, he oversaw the closing down of the Contras, who were based in Honduras.

In 1988, during Operation Golden Pheasant, US forces were sent to Honduras. This was in response to Nicaraguan attacks on Contra supply hiding places in Honduras.

The 1990s

In January 1990, Rafael Leonardo Callejas won the presidential election and took office. He focused on economic reform and reducing the government's debt. He started a movement to put the military under civilian control. He also laid the groundwork for creating a public prosecution service. In 1993, PLH candidate Carlos Roberto Reina was elected with 56% of the vote. He ran against PNH candidate Oswaldo Ramos Soto. Reina won on a promise of "moral revolution." He actively tried to prosecute corruption and those responsible for human rights abuses in the 1980s. The Reina government successfully increased civilian control over the armed forces. It also moved the national police from military to civilian authority. In 1996, Reina named his own defense minister. This broke the tradition of accepting the military's choice.

His government greatly increased the Central Bank's international reserves. It reduced inflation to 12.8% a year. It also brought back a better rate of economic growth (about 5% in 1997). Spending was kept down to achieve a 1.1% government deficit in 1997.

The Liberal Party of Honduras (PLH)'s Carlos Roberto Flores took office on January 27, 1998. He was Honduras's fifth democratically elected president since free elections returned in 1981. He won by a 10% margin over his main opponent, PNH nominee Nora Gúnera de Melgar. Flores started International Monetary Fund (IMF) programs to reform and modernize the Honduran government and economy. These focused on keeping the country financially healthy and improving its ability to compete internationally.

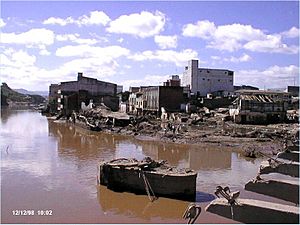

In October 1998, Hurricane Mitch caused huge damage in Honduras. More than 5,000 people died, and 1.5 million were left without homes. Damages totaled nearly $3 billion. International donors came forward to help rebuild infrastructure, giving US$1400 million in 2000.

Honduras in the 2000s and 2010s

The 2000s

In November 2001, the National Party won the presidential and parliamentary elections. The PNH gained 61 seats in Congress, and the PLH won 55. The PLH candidate Rafael Pineda was defeated by the PNH candidate Ricardo Maduro. Maduro took office in January 2002. His government focused on stopping the growth of gangs, especially Mara 18 and Mara Salvatrucha.

On November 27, 2005, the PLH candidate Manuel Zelaya defeated the PNH candidate and current Head of Congress, Porfirio "Pepe" Lobo. Zelaya became the new president on January 27, 2006.

Jose Manuel Zelaya Rosales of the Liberal Party of Honduras won the November 27, 2005, presidential elections by less than a 4% margin. This was the smallest margin ever in Honduran election history. Zelaya's campaign theme was "citizen power." He promised to increase transparency while keeping the economy stable. The Liberal Party won 62 of the 128 congressional seats, just short of a full majority.

In 2009, Zelaya caused controversy with his call for a constitutional referendum in June. This vote would decide about forming a Constitutional National Assembly to write a new constitution. The constitution clearly forbids changes to some of its rules, including the term limit for presidents. This move led to a Constitutional Crisis.

The Honduran Supreme Court issued an order to stop the referendum. Zelaya rejected this ruling and fired Romeo Vásquez Velásquez, the head of Honduras's armed forces. Vásquez had refused to help with the referendum because he did not want to break the law. The Supreme Court and Congress also said the firing was unlawful, and Vásquez was put back in his position. The President then continued to defy the Supreme Court by pushing ahead with the vote, which the Court had called "illegal." The military had taken the ballots and voting materials to a military base in Tegucigalpa. On June 27, the day before the election, Zelaya, followed by many supporters, entered the base. As Commanding Officer of the Armed Forces, he ordered the ballots and voting materials to be returned to him. Congress saw this as an abuse of power and ordered his capture.

On June 28, 2009, the military removed Zelaya from office and sent him to Costa Rica, a neutral country. Elvin Santos, the vice-president at the start of Zelaya's term, had resigned to run for president in the upcoming elections. By presidential succession, the head of Congress, Roberto Micheletti, was appointed president. However, because the United Nations and the Organization of American States opposed using military force to remove a president, most countries in the region and worldwide continued to recognize Zelaya as the President of Honduras. They called the military's actions an attack on democracy.

Honduras continued to be ruled by Micheletti's government under strong foreign pressure. On November 29, democratic general elections were held. Former Congressional president and 2005 candidate, Pepe Lobo, won.

The 2010s

Porfirio "Pepe" Lobo Sosa became president on January 27, 2010. His government focused during its first year on getting foreign countries to recognize his presidency as legitimate. They also worked to get Honduras back into the OAS.

After Lobo Sosa's presidential term, Juan Orlando Hernández defeated Xiomara Castro in the general elections in 2013. Xiomara Castro is the wife of the former president Manuel Zelaya, who was removed from office. During the first years of his presidency, economic growth helped improve the main cities' buildings and roads. However, unemployment and social unrest increased during his first term. He opened the possibility of changing the constitution, which angered many people. In 2015, the supreme court of Honduras removed a limit on how many terms a president could serve. President Juan Orlando Hernández was reelected in 2017, winning the election.

The 2020s

In September 2020, Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández announced that Honduras would move its embassy to Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Honduras became the third country in the world, after the United States and Guatemala, to have embassies to Israel in Jerusalem.

In January 2021, Honduras changed the country's constitution. The constitutional reform was supported by Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández's ruling National Party.

On November 28, 2021, the former first lady Xiomara Castro won the presidential election. She was the leftist candidate of the opposition Liberty and Refoundation Party. She won 53% of the votes to become the first female president of Honduras. On January 27, 2022, Xiomara Castro was sworn in as Honduras's president. Her husband, Manuel Zelaya, held the same office from 2006 until 2009.

|

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Honduras para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Honduras para niños

- List of presidents of Honduras

- Politics of Honduras

- Hondurans

General:

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |