Maya stelae facts for kids

Maya stelae (say: STEE-lie; one is a stela) are tall, carved stone monuments. The ancient Maya people of Mesoamerica made them. These stone pillars often stood next to low, round stones. People called these "altars," but we're not sure exactly what they were used for.

Many stelae have detailed carvings on them. Some are just plain stone. Maya people started carving these monuments during the Classic Period (250–900 AD). Having carved stelae with round altars became a special sign of Classic Maya culture. The oldest stela found in its original spot was in the big city of Tikal in Guatemala. During the Classic Period, almost every Maya kingdom in the southern lowlands set up stelae in their main city areas.

Stelae were very important to the idea of "divine kingship." This means kings were seen as having a special connection to the gods. When this idea of kingship faded, so did the making of stelae. Maya people began making stelae around 400 BC. They continued until the Classic Period ended around 900 AD. Some older monuments were even used again later. The city of Calakmul in Mexico has the most stelae found anywhere. There are at least 166, but many are not well preserved.

Hundreds of stelae have been found across the Maya region. They show many different styles. Most are upright slabs of limestone with carvings on one or more sides. These carvings often show figures and hieroglyphic writing. Some stelae, like those at Copán and Toniná, look much more three-dimensional. This was possible because of the type of stone available there. Plain stelae probably weren't painted. But most carved Maya stelae were likely painted in bright colors like red, yellow, black, and blue.

Stelae were like stone banners. They were made to celebrate the king and his achievements. The earliest ones showed stories about Maya gods. Over time, the images changed. Early Classic stelae (around 250–600 AD) from the 4th century showed influences from the big city of Teotihuacán in central Mexico. This influence lessened in the 5th century. But some small references to Teotihuacan remained. By the late 5th century, Maya kings started using stelae to mark the end of important time cycles in the Maya calendar. In the Late Classic (around 600–900 AD), images related to the Mesoamerican ballgame appeared. This also showed influence from central Mexico. As the Classic Period ended, kings began to be shown with their important lords, not just by themselves. The last known stelae were put up in 909–910 AD.

Contents

What Stelae Were Used For

Maya stelae were very important to the idea of Maya kingship. This was true from the very beginning of the Classic Period until the end (800–900 AD). The writings on the stelae at Piedras Negras helped experts understand Maya writing. These stelae were grouped around buildings. Each group seemed to tell the story of a specific person's life. They marked important dates like births, marriages, and war victories. Because of these stelae, a researcher named Tatiana Proskouriakoff figured out that the carvings were about kings and their families. Before this, people thought they were about priests and gods.

An expert named David Stuart first thought Maya people called their stelae te tun, meaning "stone trees." Later, he changed his idea to lakamtun, meaning "banner stone." Lakam means "banner" in several Mayan languages, and tun means "stone." Stuart believes this name suggests stelae were stone versions of tall banners. These banners might have stood in important places in Maya cities. Ancient Maya graffiti shows such banners. The name of the modern Lacandon Maya might even come from this word.

Maya stelae were often placed to impress people. They formed lines or other patterns in the city's main ceremonial area. Cities that had been carving stone for a long time often put their stelae with a round altar. These altars might have looked like cut tree trunks. Some think they were used for human sacrifice, because many carvings show sacrifice. Another idea is that these "altars" were actually thrones for rulers during ceremonies. Archaeologists also think they were used as stands for incense burners, sacred fires, and other offerings.

The main reason for a stela was to praise the king. Many Maya stelae only show the king of the city. They describe his actions using hieroglyphic writing. Even if the carving showed someone else, the text or scene usually connected them to the king. Stelae openly showed the king's importance and power. They displayed his wealth, fame, and family history. They also showed him holding symbols of military and divine power.

Stelae were put up to remember important events. This was especially true at the end of a kʼatun (a 20-year cycle in the Maya calendar). They also marked quarter or half kʼatun endings. The stela didn't just mark time; some believe it actually became that period of time. The writings on stelae describe how kings performed special dances and bloodletting rituals for these calendar ceremonies. At Tikal, special "twin pyramid groups" were built to celebrate the kʼatun endings. These groups showed the Maya's ideas about the universe. They had pyramids on the east and west sides, representing the sun's birth and death. On the south side, a building with nine doors stood for the underworld. On the north side was a walled area open to the sky, representing the heavens. A stela and altar pair were placed in this heavenly area. The altar was like a fitting throne for the divine king.

Calakmul had a unique tradition. They put up twin stelae showing both the king and his wife. The images on stelae stayed mostly the same during the Classic Period. This was because the messages on them needed to be easily understood. But sometimes, changes in society caused changes in the images. Stelae were great for public messages. Unlike older carvings on buildings, stelae were made for a specific king. They could be placed in public areas and even moved. This meant they could survive different building projects. By showing a recognizable ruler with fancy items, along with writing about his actions, stelae became a very effective way to spread messages in the Maya lowlands. In 7th-century Copán, king Chan Imix Kʼawiil put up seven stelae. These marked the edge of the most fertile land in the Copán valley. They also showed the city's sacred design and pointed to important places for gods in Copán's main ceremonial area.

Stelae as Sacred Objects

Maya people thought stelae were holy. They might have even believed stelae had a divine soul, making them almost living beings. Some stelae were given names in the hieroglyphic texts. They were seen as taking part in rituals held where they stood. During the Classic Period, these rituals included a kʼaltun binding ceremony. In this ritual, the stela was wrapped in cloth. This was closely connected to the kʼatun-ending calendar ceremony. A kʼaltun ritual is carved on a peccary skull found at Copán. It shows two nobles wrapping a stela and altar. Wrapping sacred objects was very important in Maya religion across Mesoamerica. It is still done by some Maya people today. We don't know the exact meaning of this act. It might have been to protect the object or to keep its sacred power inside. Wrapping stelae might be like how the modern Kʼicheʼ Maya wrap small stones used for telling the future.

A stela was not just a simple picture. It was thought to be "owned" by the person or god it showed. Stela 3 from El Zapote in Guatemala is a small monument from the Early Classic period. The front shows the rain god Yaxhal Chaak. The text says that the god Yaxhal Chaak himself was dedicated, not just his image. This suggests the stela was seen as the god's physical form. The same was true for stelae with royal portraits. They were seen as the king's supernatural form. A stela, with its altar, was like a never-ending royal ceremony in stone. David Stuart said that stelae "don't just remember past events and royal ceremonies but help the ritual act last forever." This means stelae were believed to have a magical effect. Stelae showing many people, like nobles doing a ritual or a king with war captives, might have been different. They might not have been seen as the sacred form of just one person.

Sometimes, when a new king took power, old stelae were respectfully buried. Or they might be broken. When a Maya city was attacked by a rival, the winners would loot it. One clear sign of such an attack is when the defeated city's stelae were broken and knocked down. At the end of the Preclassic period, around 150 AD, this happened to the important city of El Mirador. Most of its stelae were found smashed.

How Stelae Were Made

Sometimes, royal artists made stelae. In some cases, these artists were even the sons of kings. Other times, artists captured from defeated cities might have been forced to make stelae for the winners. This is suggested when a city's carving style appears on the monuments of its conqueror soon after a defeat. This seems to have happened at Piedras Negras. Stela 12 there shows war captives surrendering to the winning king. It is carved in the style of Pomoná, the defeated city. Archaeologists think this might also have happened with Quiriguá after it surprisingly defeated its powerful neighbor, Copán.

Stelae were usually made from limestone taken from quarries. But in the Southern Maya area, other types of stone were used. At Copán, they used volcanic tuff to make their stelae look three-dimensional. Both limestone and tuff were easy to carve when first dug out. They became harder when exposed to the weather. At Quiriguá, a hard red sandstone was used. This stone couldn't be carved in 3D like at Copán. But it was strong enough for the kings of Quiriguá to build the tallest free-standing stone monuments in the Americas.

The Maya didn't have animals to carry heavy loads. They also didn't use the wheel. So, the freshly quarried stone blocks had to be moved on rollers along the Maya causeways (raised roads). Evidence of this has been found on the causeways themselves. The blocks were carved into their final shape while still soft. Then, they hardened naturally over time. Stone was usually taken from nearby areas. But sometimes, it was moved over very long distances. Calakmul in Mexico was one of two powerful cities in the Classic Period (the other was Tikal). It brought black slate for one stela from the Maya Mountains, more than 320 kilometers (200 miles) away. Even though Calakmul made the most stelae, they used poor quality limestone. This caused most of them to wear away badly, making them hard to read. Stelae could be very big. Quiriguá Stela E is 10.6 meters (35 feet) tall from its base to the top. This includes the 3 meters (10 feet) buried underground to hold it up. This monument might be the largest free-standing stone monument in the New World. It weighs about 59 tons. Stela 1 at Ixkun is one of the tallest monuments in the Petén Basin. It is 4.13 meters (13.5 feet) high (not including the buried part). It is about 2 meters (6.5 feet) wide and 0.39 meters (1.3 feet) thick.

Maya stelae were carved with stone chisels. They probably used wooden mallets (hammers). Hammerstones made from flint and basalt were used to shape softer rocks. Smaller chisels were used for fine details. Most stelae were probably painted in bright colors like red, yellow, black, and blue. They used natural pigments from minerals and plants. At Copán and other Maya cities, some traces of these colors have been found on the monuments.

Usually, all sides of a stela were carved with human figures and hieroglyphic text. Each side was part of one big picture. Plain stelae, which were just flat slabs or stone columns, are found all over the Maya region. These plain ones seem to have never been painted or decorated with stucco (a type of plaster).

History of Stelae

Early Beginnings

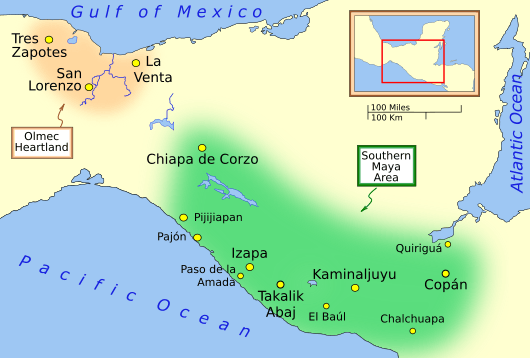

The Maya carving style for stelae appeared fully formed. It was probably influenced by earlier carved wooden monuments. But the idea of putting up stelae first came from the Olmec people on the Gulf Coast of Mexico. In the Late Preclassic period, this idea spread. It went to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and south along the Pacific Coast. Sites like Chiapa de Corzo, Izapa, and Takalik Abaj started carving Mesoamerican Long Count calendar dates onto stelae.

At Izapa, stelae showed mythological scenes. But at Takalik Abaj, they began to show rulers in the Early Classic Maya style. These carvings included calendar dates and hieroglyphic texts. It was also at Takalik Abaj and Izapa that stelae started to be paired with round altars. By about 400 BC, early Maya rulers were putting up stelae. These celebrated their achievements and showed their right to rule. At El Portón in highland Guatemala, a carved stone stela (Monument 1) was put up. Its badly worn writings seem to be a very early form of Maya writing. It might even be the oldest known Maya script. It was found with a plain altar, a common stela-altar pair. Stela 11 from Kaminaljuyu, a big highland city, is from the Middle Preclassic. It is the earliest stela to show a standing ruler. The carved Preclassic stelae from Kaminaljuyu and other cities often showed kings taking power, sacrifices, and warfare.

These early stelae showed rulers as warriors or wearing masks of Maya deities. Texts recorded dates and achievements during their rule. They also showed their connections to their ancestors. Stelae were placed in large public squares. This was so everyone could see them clearly. The practice of putting up stelae spread across the Maya area. The growth of Maya stelae happened at the same time as the idea of "divine kingship" grew among the Classic Maya. In the southern Maya area, Late Preclassic stelae showed the king's achievements and his right to rule. This made his political and religious power stronger.

At the Middle Preclassic city of Nakbe, Maya artists made some of the earliest lowland Maya stelae. They showed richly dressed people. Nakbe Stela 1 is from around 400 BC. It was broken, but it originally showed two fancy figures facing each other. This might show power being passed from one ruler to the next. It also has features that remind us of the Maya Hero Twins myth. This would be the earliest known image of them. Around 200 BC, the huge nearby city of El Mirador started putting up stela-like monuments. They had carvings that look like glyphs, but we can't read them yet. Stelae from the Late Preclassic period have also been found at El Tintal, Cival, and San Bartolo in Guatemala. Also at Actuncan and Cahal Pech in Belize.

On the Pacific Coast, El Baúl Stela 1 has a date in its writing that means 36 AD. It shows a ruler holding a staff or spear. There are two columns of writing in front of him. At Takalik Abaj, two stelae (Stela 2 and Stela 5) show power being passed from one ruler to another. Both show two richly dressed figures facing each other. There is a column of writing between them. The date on Stela 2 is from the 1st century BC at the latest. Stela 5 has two dates, the latest being 126 AD. This stela was found with a human sacrifice burial and other offerings. Stela 13 at Takalik Abaj is also from the Late Preclassic. A huge offering of over 600 ceramic pots was found at its base. Also found were 33 obsidian blades and other artifacts. Both the stela and the offering were near a Late Preclassic royal tomb. At Cuello in Belize, a plain stela was put up around 100 AD in a public plaza.

At the very end of the Preclassic Period (around 100–300 AD), cities in the highlands and along the Pacific Coast stopped making carved stelae with writing. This stop in stela production was a big sign of a general decline in the area. This decline might be linked to people moving in from the western highlands. It also might be due to the terrible eruption of the Ilopango Volcano. This eruption greatly affected the whole region.

Classic Period Stelae

In the central Petén lowlands, new ways of showing rulers to the public were needed. This was because individual rule grew in cities like Tikal. Preclassic art mostly used carvings on buildings that didn't show specific people. The existing Preclassic Petén carving styles were mixed with ideas from the highlands and Pacific Coast. This created the Early Classic Maya stela. Features once found on building carvings, like the giant masks on Preclassic pyramids, were used on stelae. For example, the "Jester God" was moved to the headdress of the ruler on Tikal Stela 29. This stela has the oldest Long Count date found in the Maya lowlands, which is 292 AD. At some Maya cities, the first stelae appeared when dynastic rule (rule by a family) began.

The usual Maya stela, with art, calendar dates, and writing about a king, only started to be put up in the Maya lowlands after 250 AD. In the late 4th century, new images appeared. These were not Maya but were linked to the huge city of Teotihuacán in central Mexico. This foreign influence is seen at Tikal, Uaxactun, Río Azul, and El Zapote in Guatemala. At Tikal, king Yax Nuun Ahiin I started this. From there, it spread to cities under his control. In the 5th century, Yax Nuun Ahiin I's son, Sihyaj Chan Kʼawiil II, stopped using these strong Teotihuacan images. He brought back images from the Pacific Coast and nearby highlands. Small references to Teotihuacan continued, like Teotihuacan war symbols. His Stela 31 was first put up in 445 AD. It was later broken and found buried in the city center, almost right above his tomb. It shows Siyaj Chan Kʼawiil II being crowned. His father floats above him as a supernatural being. This is done in the traditional Maya style. On the sides of the stela are two carvings of his father in a non-Maya style. He is dressed as a Teotihuacan warrior, holding a atlatl (spear-thrower) not used by the Maya. He also carries a shield with the face of the Mexican god Tlaloc. The back of the stela has a long hieroglyphic text. It tells the history of Tikal, including the Teotihuacan invasion that started Yax Nuun Ahiin I's family rule.

In the Early Classic period, Maya kings began to dedicate a new stela, or other monument, to mark the end of each kʼatun cycle. A kʼatun is 7,200 days, which is almost 20 years. At Tikal, king Kan Chitam was the first to do this in the late 5th century. Stela 9 from Tikal is the first dated monument put up to mark a period of time. It was put up in 475 AD.

Late Classic Stelae

In the Late Classic period, the carved images of rulers on stelae stayed much the same as in the Early Classic. They appeared from the side, filling almost the whole space, surrounded by a frame. Images related to the Mesoamerican ballgame started to appear in the Maya lowlands during the Late Classic. Maya kings were shown as warriors wearing costumes from the Mexican highlands. These included parts like the foreign god Tlaloc and the Teotihuacan serpent. Such images appear in the Late Classic on stelae from Naranjo, Piedras Negras, and the Petexbatún cities of Dos Pilas and Aguateca. At Dos Pilas, two stelae show the city's king in costume. He looks like a jaguar and an eagle, which were common in Mexican warrior groups. By 790 AD, stelae were being put up by the Maya across the entire central and southern Maya lowlands. This area was about 150,000 square kilometers (58,000 square miles).

In the north, Coba on the eastern side of the Yucatán Peninsula put up at least 23 large stelae. Even though they are badly worn, their style and texts connect them to cities from the Petén Basin. At the southern edge of the Maya region, Copán developed a new style of stelae with high carvings. In 652 AD, the twelfth king Chan Imix Kʼawiil arranged a series of these stelae. They marked the sacred design of the city and celebrated his rule and ancestors. His son and successor Uaxaclajuun Ubʼaah Kʼawiil further developed this high-carving style. He put up many detailed stelae in the city's Great Plaza. These carvings were almost fully three-dimensional. Both of these kings focused on their own images on their stelae. They stressed their place in the family line to justify their rule. This might have been because the eleventh king of Copán died, causing a break in the family line.

After Quiriguá defeated its powerful neighbor Copán in 738 AD, it brought huge blocks of red sandstone. These came from quarries 5 kilometers (3 miles) from the city. They carved a series of enormous stelae. These were the biggest single-stone monuments ever put up by the Maya. Stela E is over 10 meters (33 feet) high and weighs more than 60 tons. These stelae were shaped with a square cross-section and carved on all four sides. They usually show two images of the Quiriguá king, on the front and back. These carvings are less raised than those at Copán. They have very complex panels of hieroglyphic text. These are some of the most skillfully made Maya writings in stone. The stelae have lasted well and show how precise the carvers were.

End of the Classic Period

The decline in putting up stelae is linked to the decline of "divine kingship." This started in the Late Preclassic. At first, stelae showed the king with symbols of power. Sometimes he stood over defeated enemies. Sometimes he was with his wives or his heir. By the Terminal Classic, kings were sharing stelae with their important lords. These lords also played a big part in the events shown. This meant power was spreading out. Kings had to make deals with high-ranking nobles to keep their power. But this made the king's rule weaker. As the king's power lessened and his lords' power grew, the lords started putting up their own stelae. This used to be only for the king. Some of these lords broke away to form their own small states. But even this didn't last, and they also stopped putting up monuments.

In the Pasión River region of Petén, rulers started to be shown as ballplayers on stelae. Seibal was the first site in the region to show its rulers this way. Seventeen stelae were put up at Seibal between 849 and 889 AD. They show a mix of Maya and foreign styles. One shows a lord wearing the bird-beaked mask of Ehecatl, the central Mexican wind god. A Mexican-style speech scroll comes from his mouth. Some of these look similar to paintings at Cacaxtla, a non-Maya site in central Mexico. This mixed style suggests that the kings of Seibal were Maya lords. They were adapting to changing political times by using symbols from both lowland Maya and central Mexican cultures. Some of the more foreign-looking stelae even have non-Maya calendar symbols. Stelae at Oxkintok, in the north of the Yucatán Peninsula, divided the stela's face into up to three levels. Each level had a different scene, usually of a single figure, male or female. The way human figures were shown was simpler and rougher than in the south. They lacked individual details among the political and religious symbols.

As the Classic Maya collapse spread across the Maya region, city after city stopped putting up stelae. These stelae recorded their family achievements. At the important city of Calakmul, two stelae were put up in 800 AD and three more in 810 AD. But these were the last, and the city became quiet. At Oxkintok, the last stela was put up in 859 AD. Stela 11, dated to 869 AD, was the last monument ever put up at the once great city of Tikal. The last known Maya stelae with a Long Count calendar date are Toniná Monument 101 (909 AD) and Stela 6 from Itzimté (910 AD).

After the Classic Period

At Copán, people continued to leave offerings around the city's stelae until at least 1000 AD. This might mean that some important people still remembered their ancestors. Or it could be that highland Maya people still visited the city as a sacred place long after it was in ruins. A few carved stelae once stood at Cerro Quiac in the Guatemalan Highlands. It's thought that Mam Maya put them up in the 13th or 14th century. At Lamanai in Belize, Classic period stelae were moved onto two small platforms from the 15th or 16th century. At La Milpa, also in Belize, a small group of Maya people started leaving offerings of pottery from the time of the Spanish arrival (late 16th century) at stelae. Perhaps they hoped to ask their ancestors for help against the Spanish. A plain stela in Twin Pyramid Group R at Tikal was moved by local people sometime after the Classic Period. Its altar was also moved but left some distance from its original spot. Some plain stelae were put up at Topoxté in the Petén Lakes region of Guatemala after the Classic Period. These might have been covered in stucco and painted. This could show a return to the kʼatun-ending ceremonies from the Classic Period. It also might show connections with the northern Yucatán.

Discovery of Stelae

One of the first descriptions of Maya stelae comes from Diego Garcia de Palacio. He was a Spanish official who wrote about six stelae at Copán in a letter to King Philip II of Spain in 1576. Juan Galindo, the governor of Petén, visited Copán in 1834. He noticed the carved high-relief stelae there. Five years later, American diplomat John Lloyd Stephens and British artist Frederick Catherwood traveled to Central America. They went to Copán and described fifteen stelae in Stephens' book, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas and Yucatán, published in 1841. Stephens and Catherwood saw red paint on some of the Copán stelae. Stephens tried to buy the ruins of Quiriguá but failed. He bought Copán for US$50 (about $1,800 today). He wanted to ship the stelae to New York for a new museum. But he couldn't ship the monuments down the Copán River because of rapids. So, all the stelae stayed at the site. While Stephens was busy elsewhere, Catherwood briefly looked at the stelae at Quiriguá. He found them very hard to draw without a special drawing tool because they were so tall. Ambrosio Tut, governor of Petén, and colonel Modesto Méndez, the chief judge, visited the ruins of Tikal in 1848. They were with Eusebio Lara, who drew some of the monuments there. In 1852, Modesto Méndez discovered Stela 1 and Stela 5 at Ixkun. English explorer Alfred Maudslay arrived at Quiriguá in 1881. He cleared plants from the stelae. Then he traveled to see the stelae at Copán. In the early 1900s, an expedition by the Carnegie Institution led by American Mayanist Sylvanus Morley found a stela at Uaxactun. This time marked a change. Instead of individual explorers, large organizations started funding archaeological work.

Where to See Stelae Today

You can see many impressive stelae today. There's a great collection of 8th-century monuments at Quiriguá. Also, 21 stelae are in the sculpture museum at Tikal National Park. Both are World Heritage Sites in Guatemala. Calakmul in Mexico is another World Heritage site. It has many stelae that are considered amazing examples of Maya art. Copán in Honduras, also a World Heritage Site, has over 10 beautifully carved stelae in its main area.

The Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología ("National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology") in Guatemala City shows many beautiful stelae. These include three 9th-century stelae from Machaquilá. There's also an 8th-century stela from Naranjo. Other stelae are from Ixtutz, Kaminaljuyu, La Amelia, Piedras Negras, Seibal, Tikal, Uaxactun, and Ucanal. The Museo Nacional de Antropología ("National Museum of Anthropology") in Mexico City has a few Maya stelae on display. The San Diego Museum of Man in California has copies of the stelae from Quiriguá. These were made in 1915 for an exhibition.

Many Maya archaeological sites have stelae on display where they were originally found. In Guatemala, these include Aguateca, Dos Pilas, El Chal, Ixkun, Nakum, Seibal, Takalik Abaj, Uaxactun, and Yaxha. In Mexico, you can see stelae at Yaxchilan and the site museum at Toniná.

Protecting Stelae from Harm

In modern times, stelae have been in danger from people who steal them to sell on the international art market. Many stelae are in remote areas. Their large size and weight make it hard to move them whole. People who steal them use different ways to cut or break a stela to make it easier to carry. These methods include power saws, chisels, acid, and heat. If a monument is well preserved, thieves try to cut off its carved face. Even if they succeed, this damages the writings on the sides. At worst, this method shatters the stela's face. Then, any small pieces of carving that can be saved are taken to be sold.

In the past, pieces of famous monuments have been bought by museums and private collectors in America. When such monuments are taken from their original places, their historical meaning is lost. Some museums have said that buying these pieces helps preserve them. But no stela has been sold in as good condition as it was in its original location. After 1970, fewer Maya stelae were available on the New York art market. This was because of a treaty with Mexico. This treaty makes sure that stolen pre-Columbian sculptures taken from the country after the treaty date are returned. In the early 1970s, some museums, like the University of Pennsylvania, stopped buying archaeological items that didn't have a legal history. This included where they came from, who owned them before, and an export license. Harvard University also started a similar rule in the early 1970s.

In 1972, Stela 5 at Ixkun was well preserved. But thieves smashed it into pieces. They heated it until it broke, then stole several pieces. An archaeologist named Ian Graham saved some remaining fragments. They were moved to the mayor's office in Dolores, Petén. Later, they were used as building material. But in 1989, the Atlas Arqueológico de Guatemala found them again. They were moved to an archaeological lab. At the nearby site of Ixtonton, 7.5 kilometers (4.7 miles) from Ixkun, most of the stelae were stolen before the site was reported to the Guatemalan authorities. By the time archaeologists visited in 1985, only 2 stelae were left.

In 1974, a dealer named Hollinshead illegally removed Machaquilá Stela 2 from the Guatemalan jungle. He and others involved were charged in the United States under the National Stolen Property Act of 1934. They were the first people found guilty under this law for items related to a country's national heritage. This law helps stop the trade of stolen property. Courts have said it applies to goods brought into the United States from other countries. This means it can be used for stolen cultural property.

Under Guatemalan law, Maya stelae and other archaeological items belong to the Guatemalan government. They cannot be taken out of the country without permission. Machaquilá Stela 2 was well known before it was stolen. So, it was easy to prove its illegal removal. The stela was cut into pieces. Its face was sawn off and moved to a fish packing factory in Belize. There, it was packed into boxes and shipped to California. The Federal Bureau of Investigation seized it after it was offered for sale to different places. The stolen part of the stela was returned to Guatemala. It is now stored at the Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología in Guatemala City.

Stealing artifacts is linked to a country's economic and political situation. More stealing happens during times of trouble. It also seems that art collectors sometimes order stelae, or parts of them, to be stolen. They look through archaeological books for pieces they want. Examples of this are at Aguateca and El Perú in Guatemala. There, only the best preserved writings and human faces were cut away.

Images for kids

-

Aguateca Stela 6 on display at the Chilean Museum of Pre-Columbian Art in Santiago de Chile.

See also

In Spanish: Estela maya para niños

In Spanish: Estela maya para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |