Mesoamerican Long Count calendar facts for kids

The Mesoamerican Long Count calendar is a special way of counting days that was used by ancient cultures in Mesoamerica, especially the Maya. It's often called the Maya Long Count calendar. This calendar counts the number of days that have passed since a mythical starting date. This date is believed to be August 11, 3114 BCE in our modern calendar. The Long Count calendar was carved onto many ancient stone monuments.

Contents

Understanding Ancient Calendars

Before Europeans arrived in Mesoamerica, people there used two main calendars. One was the 260-day Tzolkʼin calendar, and the other was the 365-day Haabʼ calendar. The Aztecs had similar calendars called the Tonalpohualli and Xiuhpohualli.

When you combine a date from the Haabʼ and a date from the Tzolkʼin, you get a unique day. This combination repeats only every 18,980 days, which is about 52 years. This period is known as the Calendar Round. To keep track of dates over much longer times, the Mesoamericans used the Long Count calendar.

How the Long Count Works

The Long Count calendar pinpoints a date by counting days from its starting point. This starting point is usually August 11, 3114 BCE in our proleptic Gregorian calendar.

The Maya believed that the world of humans was created when 13 bʼakʼtuns were completed on August 11, 3114 BCE. On this day, a god called Raised-up-Sky-Lord set three special stones. This act helped to lift the sky from the water, making the world visible.

Instead of using a base-10 system (like our numbers 0-9), the Long Count used a modified base-20 system. This means that numbers usually went up to 19 before rolling over to the next unit, like how our numbers go up to 9 before rolling over to the next ten. However, one specific unit, the tun, rolled over at 18 instead of 20. This made the calculations a bit different.

The name bʼakʼtun was actually made up by modern experts. The full Long Count system was not used anymore when the Spanish arrived in the Yucatán Peninsula. However, shorter versions of the calendar were still in use.

| Long Count unit |

How many smaller units? |

Days | Approximate Solar Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Kʼin | 1 | ||

| 1 Winal | 20 Kʼin | 20 | |

| 1 Tun | 18 Winal | 360 | 1 |

| 1 Kʼatun | 20 Tun | 7,200 | 20 |

| 1 Bʼakʼtun | 20 Kʼatun | 144,000 | 394 |

| 1 Piktun | 20 Bʼakʼtun | 2,880,000 | 7,885 |

| 1 Kalabtun | 20 Piktun | 57,600,000 | 157,704 |

| 1 Kʼinchiltun | 20 Kalabtun | 1,152,000,000 | 3,154,071 |

| 1 Alautun | 20 Kʼinchiltun | 23,040,000,000 | 63,081,429 |

| 1 Hablatun | 20 Alautun | 460,800,000,000 | 1,261,628,585 |

Ancient Numbers and Dates

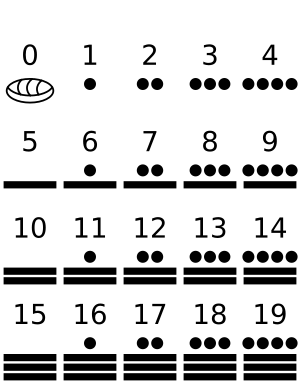

Long Count dates were written using special Mesoamerican numbers. A dot meant '1', and a bar meant '5'. A shell-shaped symbol was used for zero. The Long Count calendar is one of the earliest examples in history where the idea of "zero" was used as a placeholder in numbers.

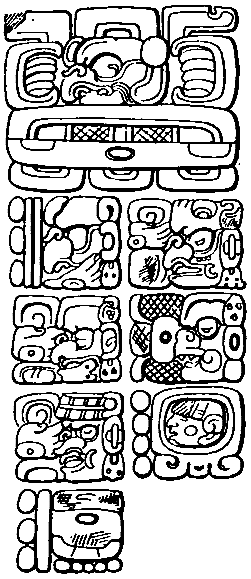

On Maya monuments, a Long Count date would usually start with a special symbol. Then came the five numbers of the Long Count. After that, the date from the Calendar Round (Tzolkʼin and Haabʼ) was added. Sometimes, extra information about the moon's age was also included. The rest of the text would then describe what happened on that date.

First Long Count Records

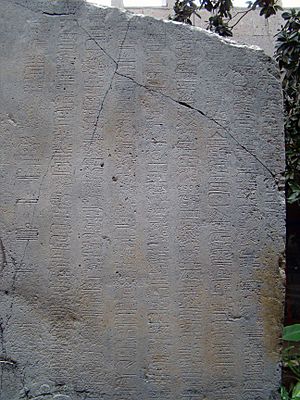

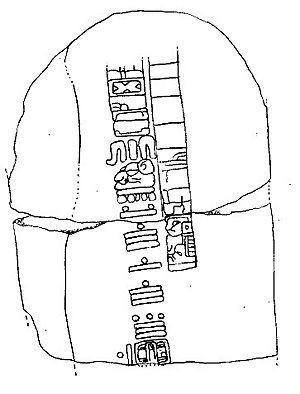

The oldest known Long Count carving was found on Stela 2 at Chiapa de Corzo, Mexico. It shows a date from 36 BCE. Another carving from Takalik Abaj, Guatemala, might be even older, but its date is harder to read.

Here are some of the earliest Long Count inscriptions found:

| Archaeological site | Name | Gregorian date | Long Count | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takalik Abaj | Stela 2 | 236 – 19 BCE | 7.(6,11,16).?.?.? | Retalhuleu, Guatemala |

| Chiapa de Corzo | Stela 2 | December 6, 36 BCE or October 9, 182 CE |

7.16.3.2.13 or 8.7.3.2.13 |

Chiapas, Mexico |

| Tres Zapotes | Stela C | September 1, 32 BCE | 7.16.6.16.18 | Veracruz, Mexico |

| El Baúl | Stela 1 | 11 – 37 CE | 7.18.9.7.12, 7.18.14.8.12, 7.19.7.8.12, or 7.19.15.7.12 |

Escuintla, Guatemala |

| Takalik Abaj | Stela 5 | August 31, 83 CE or May 19, 103 CE |

8.2.2.10.15 or 8.3.2.10.15 |

Retalhuleu, Guatemala |

| Takalik Abaj | Stela 5 | June 3, 126 CE | 8.4.5.17.11 | Retalhuleu, Guatemala |

| La Mojarra | Stela 1 | May 19, 143 CE | 8.5.3.3.5 | Veracruz, Mexico |

| La Mojarra | Stela 1 | July 11, 156 CE | 8.5.16.9.7 | Veracruz, Mexico |

| Near La Mojarra | Tuxtla Statuette | March 12, 162 CE | 8.6.2.4.17 | Veracruz, Mexico |

Many of these early Long Count carvings were found outside the main Maya area. This suggests that the Long Count calendar might have been developed by other Mesoamerican cultures before the Maya started using it widely. For example, some carvings use an Epi-Olmec script, not Maya writing.

The first carving that is clearly Maya is Stela 29 from Tikal. It has a Long Count date of 292 CE, which is over 300 years after the Chiapa de Corzo carving.

More recently, a stone block from San Bartolo (Maya site) in Guatemala (around 300 BCE) was found. It might contain the earliest Maya hieroglyphic text and possibly the earliest sign of Long Count notation in Mesoamerica.

Connecting Long Count to Our Calendar

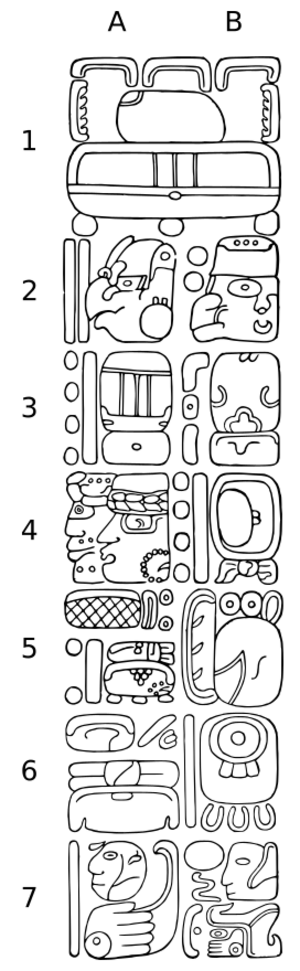

This is the second oldest Long Count date yet discovered. The numerals 7.16.6.16.18 translate to September 1, 32 BCE (Gregorian). The glyphs surrounding the date are what is thought to be one of the few surviving examples of Epi-Olmec script.

To match the Maya Long Count with our Western calendars, experts use a "correlation constant." This number tells us how many days passed between the Maya creation date (13.0.0.0.0) and a specific date in our calendar. The most accepted constant is 584,283 days, known as the "GMT correlation."

Using the GMT correlation, the Maya creation date of 13.0.0.0.0 corresponds to August 11, 3114 BCE in the Proleptic Gregorian calendar. This correlation is supported by historical records, astronomical observations, and archaeological findings.

- Historical Evidence: Old Spanish writings and Maya books from after the conquest mention Maya calendar dates alongside European dates. These records consistently match the GMT correlation. For example, the fall of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, on August 13, 1521, matches a specific Maya calendar date that fits the GMT correlation. Many modern indigenous communities in Mexico and Guatemala still use parts of the ancient calendars, and their practices also support the GMT correlation.

- Astronomical Evidence: Ancient Maya carvings often include details about the moon's age or eclipses. When these dates are converted using the GMT correlation, they match modern astronomical calculations very well. The Dresden Codex, an ancient Maya book, contains tables for Venus and eclipses. Dates from these tables, when converted with the GMT correlation, align closely with modern astronomy.

- Archaeological Evidence: Scientists have used carbon dating on wooden objects from Maya sites that have Long Count dates carved on them. For example, wood from Tikal carved with a date equivalent to 741 AD (using GMT) had an average carbon date of 746±34 years, which is a very close match.

Today, 27 February 2026 (UTC), in the Long Count is 13.0.13.6.16 (using GMT correlation).

| Name | Correlation |

|---|---|

| Bowditch | 394,483 |

| Willson | 438,906 |

| Smiley | 482,699 |

| Makemson | 489,138 |

| Modified Spinden | 489,383 |

| Spinden | 489,384 |

| Teeple | 492,622 |

| Dinsmoor | 497,879 |

| −4CR | 508,363 |

| −2CR | 546,323 |

| Stock | 556,408 |

| Goodman | 584,280 |

| Martinez–Hernandez | 584,281 |

| GMT | 584,283 |

| Modified Thompson 1 | 584,284 |

| Thompson (Lounsbury) | 584,285 |

| Pogo | 588,626 |

| +2CR | 622,243 |

| Böhm & Böhm | 622,261 |

| Kreichgauer | 626,927 |

| +4CR | 660,203 |

| Fuls, et al. | 660,208 |

| Hochleitner | 674,265 |

| Schultz | 677,723 |

| Escalona–Ramos | 679,108 |

| Vaillant | 679,183 |

| Weitzel | 774,078 |

| Long Count | (proleptic before 1582) Gregorian date GMT (584,283) correlation |

Julian day number |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0.0.0.0 (13.0.0.0.0) |

Mon, Aug 11, 3114 BCE | 584,283 |

| 1.0.0.0.0 | Thu, Nov 13, 2720 BCE | 728,283 |

| 2.0.0.0.0 | Sun, Feb 16, 2325 BCE | 872,283 |

| 3.0.0.0.0 | Wed, May 21, 1931 BCE | 1,016,283 |

| 4.0.0.0.0 | Sat, Aug 23, 1537 BCE | 1,160,283 |

| 5.0.0.0.0 | Tue, Nov 26, 1143 BCE | 1,304,283 |

| 6.0.0.0.0 | Fri, Feb 28, 748 BCE | 1,448,283 |

| 7.0.0.0.0 | Mon, Jun 3, 354 BCE | 1,592,283 |

| 8.0.0.0.0 | Thu, Sep 5, 41 CE | 1,736,283 |

| 9.0.0.0.0 | Sun, Dec 9, 435 | 1,880,283 |

| 10.0.0.0.0 | Wed, Mar 13, 830 | 2,024,283 |

| 11.0.0.0.0 | Sat, Jun 15, 1224 | 2,168,283 |

| 12.0.0.0.0 | Tue, Sep 18, 1618 | 2,312,283 |

| 13.0.0.0.0 | Fri, Dec 21, 2012 | 2,456,283 |

| 14.0.0.0.0 | Mon, Mar 26, 2407 | 2,600,283 |

| 15.0.0.0.0 | Thu, Jun 28, 2801 | 2,744,283 |

| 16.0.0.0.0 | Sun, Oct 1, 3195 | 2,888,283 |

| 17.0.0.0.0 | Wed, Jan 3, 3590 | 3,032,283 |

| 18.0.0.0.0 | Sat, Apr 7, 3984 | 3,176,283 |

| 19.0.0.0.0 | Tue, Jul 11, 4378 | 3,320,283 |

| 1.0.0.0.0.0 | Fri, Oct 13, 4772 | 3,464,283 |

The 2012 Event and the Long Count

According to the Popol Vuh, a sacred book of the Kʼicheʼ Maya, humans live in the fourth world. The book describes how the gods tried to create the world three times before finally succeeding with the fourth world, where people were placed. In the Maya Long Count, the previous creation ended when the 13th bʼakʼtun cycle was completed.

Many people heard about the Long Count calendar because of the year 2012. The previous creation cycle ended on a Long Count date of 12.19.19.17.19. Another 12.19.19.17.19 happened on December 20, 2012. The next day, December 21, 2012, marked the start of the 14th bʼakʼtun (13.0.0.0.0).

Some Maya carvings even talk about events far into the future, beyond 2012. These are often "distance dates," where a Long Count date is given, and a number is added to it to find a future date.

For example, a carving at the Temple of Inscriptions in Palenque mentions an anniversary for a famous ruler named Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal. This date is over 4,000 years in the future from Pakal's time! It falls on October 21, 4772. This date is just eight days after the completion of the 1st piktun, which is an even longer time unit than a bʼakʼtun.

Despite all the talk about 2012, experts say the Maya did not believe the world would end then. Sandra Noble, an expert on Mesoamerican studies, said that for the ancient Maya, reaching the end of a cycle was a huge celebration. She called the idea of 2012 being a "doomsday event" a "complete fabrication." Another expert, E. Wyllys Andrews V, said, "We know the Maya thought there was one before this, and that implies they were comfortable with the idea of another one after this."

Higher Orders of Time

Beyond the bʼakʼtun, there are four more units of time that were rarely used: piktun, kalabtun, kʼinchiltun, and alautun. Each of these units is 20 times larger than the one before it. These names were created by modern scholars.

Some ancient carvings show the creation date using a very large number of 13s. For example, a monument from Coba shows the creation date as 13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.0.0.0.0. Some experts believe these 13s simply meant "completion" rather than an actual number.

Most inscriptions that use these very long time periods are "distance dates." They give a starting date, a number of days to add or subtract, and then the resulting Long Count date.

The Dresden codex, an ancient Maya book, also uses "Ring Numbers" to calculate dates. These numbers help figure out specific dates within the codex's tables.

See also

- Aztec calendar

- Maya astronomy

- Maya calendar

- Maya codices

- Mesoamerican calendars

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |