Maya astronomy facts for kids

Maya astronomy is how the ancient Maya people in Mesoamerica studied the sky. They watched the Moon, planets, the Milky Way, and the Sun. The Classic Maya, especially, were amazing astronomers. They had a very accurate way of tracking the sky, even without telescopes!

They used their own writing system and number system to record their observations. For example, their guess for how long a lunar month was, was better than what Europeans knew at the time. Their calculation for the length of a tropical solar year was also more accurate than the Spanish when they first arrived. Many Maya temples were even built to line up with important events in the sky.

Contents

Maya and European Calendars

European Calendar

In 46 BC, the Roman leader Julius Caesar created a calendar. It had 12 months, making a year of 365 days, with an extra day every four years (a leap year). This was the Julian calendar.

Over time, this calendar became a bit off from the actual solar year. So, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII changed it. He removed 10 days from the calendar to fix the problem. He also made a new rule for leap years: century years (like 1700 or 1800) are only leap years if they can be divided by 400. This is the Gregorian calendar we use today.

Julian Days

Astronomers use a special way to count time called a Julian day. It's a number that tells you how many days (and parts of a day) have passed since noon on January 1, 4713 BC. They start at noon because they are often watching things in the night sky.

Maya Calendars

The Maya had three main calendars:

- The Long Count was a way to count every single day from a mythical creation date. It's like a very long timeline.

- The Tzolk'in was a 260-day calendar. It combined numbers (1 to 13) with 20 day names. This calendar was very important for religious events and planning farming. Each of the 260 days was seen as a god or goddess.

- The Haab' was a 365-day year. It had 18 months of 20 days each, plus five "unlucky" days at the end.

When the Tzolk'in and Haab' calendars were used together, it was called a Calendar Round. This combination of dates repeated every 18,980 days, which is about 52 years.

Connecting Maya and European Calendars

To compare Maya dates with our calendar, experts use a special number called the Julian day number for the Maya's starting date of their current creation. This helps us understand when Maya events happened in our own timeline.

Where We Find Maya Sky Records

Maya Books (Codices)

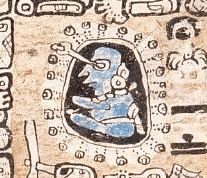

When the Spanish arrived, the Maya had many books made from folded tree bark. Sadly, most of these books were burned by the Spanish. Only four of these special books, called codices, still exist today.

- The Dresden Codex is like an astronomy book. It has lots of information about the sky.

- The Madrid Codex has almanacs and horoscopes, which helped Maya priests with ceremonies.

- The Paris Codex contains predictions and a Maya zodiac (like our star signs).

- The Grolier Codex is mainly about the planet Venus.

A librarian named Ernst Förstemann figured out that the Dresden Codex was an astronomy book in the early 1900s.

Maya Stone Monuments

Maya Stelae

The Maya built many tall stone monuments called stelae. These stones often had Long Count dates carved on them. They also included details about the Moon, like how many days into the current lunar cycle it was. Some stelae even recorded special events, like an eclipse warning on Quirigua Stela E.

Carved Texts

Many Maya temples have carved texts with information about dates and astronomy.

How the Maya Watched the Sky

The Maya watched the sky with their bare eyes, without telescopes. They paid close attention to where the Sun, Moon, and planets rose and set. They often built their cities and buildings to line up with these important sky events. The Maya also believed that the positions of planets and stars showed the will of their gods.

Some wells in Maya ruins were also used to watch the Sun pass directly overhead.

One of the most famous Maya observatories is the Caracol at Chichen Itza. This round building was designed to track the path of Venus throughout the year. Its staircases and alignments point to where Venus would appear at certain times.

Maya Sky Observations

The Sun

The Maya knew about the solstices (longest and shortest days) and equinoxes (when day and night are equal). They showed this knowledge in how they built their temples. Even more important to them were the zenithal passage days. These are the two days each year when the Sun passes directly overhead in tropical regions. Many Maya buildings were made to observe this. For example, at Xochicalco, an underground chamber had a hole in the ceiling. On May 15 and July 29, the Sun's light would shine directly onto a sun image on the floor.

The Maya also knew that their 365-day Haab' year was a bit shorter than the actual tropical year (which is about 365.2422 days). They had very accurate ways to calculate this difference. One calculation showed that the Haab' year lost one day every 1,508 days. This means 1,508 Haab' years were equal to 1,507 tropical years.

Building Alignments

Experts like Anthony Aveni and Horst Hartung have studied how Maya buildings are lined up. They found that many buildings face certain directions, often related to where the Sun rises or sets on important dates like the solstices. These alignments were important for farming and religious ceremonies.

For example, at the Caracol in Chichen Itza, some alignments point to the sunrise on the summer solstice and the sunset on the winter solstice. One window in the Caracol's round tower even allowed people to see the sunset on the equinoxes.

Other places with solar observatories include Uaxactun, Oxkintok, and Yaxchilan.

The Moon

Many Maya carvings include details about the Moon. They recorded how many days had passed in the current lunar cycle and how long that cycle was. They also tracked the Moon's position in a series of six lunar cycles.

The Maya counted the start of the lunar cycle about two days after what we call the "New Moon" today. This was either the first day the old crescent Moon could no longer be seen, or the first day the new thin crescent Moon could be seen.

Building Alignments

Some Maya buildings are also lined up with the Moon's extreme positions on the horizon. These are mostly found on the Northeast Coast of the Yucatan, where the goddess Ixchel, linked to the Moon, was very important.

Mercury

Pages in the Dresden Codex include a special almanac for both Venus and Mercury. This almanac, which covers 2340 days, closely matches the cycles of Venus and Mercury. It also mentions the summer solstice and special ceremonies.

Venus

Venus was incredibly important to the Maya. They watched its cycles very closely. The Maya connected Venus with war. They would even plan battles and sacrifice captured enemies based on where Venus was in the sky.

Venus appears and disappears from our view as it orbits the Sun. It becomes invisible when it passes behind the Sun or between Earth and the Sun. A dramatic event is when it disappears as an evening star and then reappears as a morning star about eight days later. The full cycle of Venus is about 584 days.

Dresden Codex The Dresden Codex has a Venus almanac. It tracks when Venus first appears and disappears as the "morning star" and "evening star." The Maya thought the first appearance of Venus as the morning star was a dangerous time. This table was used for over 100 years, from the 900s to the 1300s.

The Grolier Codex The Grolier Codex also lists dates for Venus's appearances and disappearances, similar to the Dresden Codex.

Building Alignments The Caracol at Chichen Itza has windows that were used to watch Venus. Some alignments of the building point to Venus's extreme positions in the sky.

Building 22 at Copan is called the Venus temple because it has Venus symbols carved on it. It has a narrow window to observe Venus on certain dates.

The Governors Palace at Uxmal also has alignments related to Venus. From a nearby hill, people could watch Venus's northern extreme over the palace. The building is decorated with many masks of Chaac, the rain god, with Venus symbols under their eyes.

Mars

The Dresden Codex has information about Mars, and there's also a partial Mars almanac in the Madrid Codex.

One table in the Dresden Codex tracks Mars's 780-day cycle. It highlights the period when Mars appears to move backward in the sky (called retrograde motion), which is when it's brightest. This table is from around 818 AD.

Jupiter and Saturn

Saturn and especially Jupiter are two of the brightest objects in the night sky. As Earth passes these planets in their orbits, they sometimes appear to stop and move backward for a while before continuing their path. This is called "apparent retrograde motion."

Inscriptions Experts have found that dates of important ceremonies at Palenque often matched when Jupiter was in a special position in its retrograde motion. They also believe the Maya celebrated when Jupiter, Saturn, or Mars were very close together in the sky.

Some stone carvings also show dates that are about 378 days apart, which is close to the cycle of Saturn. These dates often fell just before Saturn ended its backward motion.

Eclipses

The Dresden Codex The Dresden Codex has an eclipse table. This table warned about all solar and most lunar eclipses. It covered about 33 years and could be reused for centuries. It also connected eclipses with the cycles of Venus and other sky events.

Eclipses happen when the Moon's path crosses the Sun's path. This occurs twice a year during "eclipse seasons." The Dresden Codex table gives dates for these seasons.

The Madrid Codex The Madrid Codex also has an eclipse almanac, similar to the one in the Dresden Codex. This table connects eclipses with rain, drought, and farming cycles.

The Paris Codex The Paris Codex mentions historical astronomical events from the 400s to the 700s. These include eclipses and references to Venus and its relationship to constellations.

Inscriptions Lord Kan II of Caracol had an altar installed in a ball court with carvings that marked important dates. He used dates of major sky events for these. For example, a total lunar eclipse in 553 AD marked his grandfather's rise to power. A solar eclipse in 562 AD was linked to a "star war" against Tikal.

The Stars

The Maya identified 13 constellations along the ecliptic (the Sun's path through the sky). These are shown in an almanac in the Paris Codex. Each constellation was linked to an animal. These animal pictures also appear in the Madrid Codex, where they are connected to eclipses, Venus, and Haab' rituals.

Paris Codex Pages in the Paris Codex show a zodiac almanac. It has five rows, each with 364 days, divided into 13 sections of 28 days. It shows animals, including a scorpion, hanging from a skyband, and eclipse symbols. This dates back to the 700s.

Madrid Codex The longest almanac in the Madrid Codex has information about farming, ceremonies, and other topics. It includes details about eclipses, Venus cycles, and zodiac constellations. This almanac is from the mid-1400s.

The Milky Way

The Milky Way looks like a hazy band of faint stars across the night sky. It's actually the flat disk of our own galaxy, seen from the inside. It crosses the Sun's path at a high angle. Its most noticeable part is a large dust cloud that creates a dark gap.

While there isn't a specific Milky Way almanac in the Maya codices, it is mentioned in other almanacs that deal with different sky events.

Precession of the Equinoxes

The equinoxes slowly shift westward along the Sun's path in the sky, compared to the "fixed" stars. This movement takes about 26,000 years to complete one full cycle.

Some experts believe that the "Serpent Numbers" in the Dresden Codex might show that the Maya knew about this slow shift of the equinoxes. They think the Maya might have calculated this by watching lunar eclipses at certain times of the year. However, other experts disagree with this idea.

See also

In Spanish: Astronomía maya para niños

In Spanish: Astronomía maya para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |