Sandinista National Liberation Front facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sandinista National Liberation Front

Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Abbreviation | FSLN |

| Secretary-General | Daniel Ortega |

| Founder |

|

| Founded | 19 July 1961 (64 years, 217 days) |

| Headquarters | Leal Villa De Santiago De Managua, Managua |

| Newspaper | La Voz del Sandinismo |

| Youth wing | Sandinista Youth |

| Women's wing | AMNLAE |

| Armed wing | Sandinista Popular Army |

| Membership (1990) | <95,700 |

| Ideology | Sandinismo

Historical: |

| Political position | Left-wing to far-left |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| National affiliation | United Alliance Nicaragua Triumphs |

| Regional affiliation | Parliamentary Left Group (Central American Parliament) |

| Continental affiliation | São Paulo Forum COPPPAL |

| International affiliation | For the Freedom of Nations! |

| Union affiliate | Sandinista Workers' Centre |

| Colors | Official: Red Black Customary: Carmine red |

| Slogan | Cristiana, Socialista, Solidaria |

| National Assembly |

75 / 90

|

| Central American Parliament |

15 / 20

|

| Flag | |

|

|

The Sandinista National Liberation Front (in Spanish: Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, or FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas. The party is named after Augusto César Sandino, a Nicaraguan hero who fought against the U.S. occupation of Nicaragua in the 1930s.

In 1979, the FSLN led the Nicaraguan Revolution and overthrew the dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. This ended the rule of the Somoza family, which had controlled Nicaragua for over 40 years. The Sandinistas then formed a new government.

From 1979 to 1990, the Sandinistas ruled Nicaragua. They started programs to teach people to read, gave land to farmers, and improved healthcare. However, they were also criticized for harming human rights, including mistreating indigenous people. Their government also struggled with a bad economy.

The United States opposed the Sandinista government. In 1981, the U.S. began to support a group of rebel fighters called the Contras, who fought to overthrow the Sandinistas. This led to a long and difficult civil war. In 1990, the FSLN lost an election to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro and left power peacefully.

Today, the FSLN is once again the ruling party in Nicaragua. Daniel Ortega, a long-time Sandinista leader, was reelected president in 2006 and has been in power ever since. His government has been criticized for becoming less democratic.

Contents

History

Who was Augusto César Sandino?

The Sandinistas named their party after Augusto César Sandino (1895–1934). He was a nationalist leader who led a rebellion against U.S. soldiers occupying Nicaragua in the 1920s and 1930s.

In 1934, Sandino was killed by the Nicaraguan National Guard. This police force was led by Anastasio Somoza García, who soon became the country's dictator. His family, the Somozas, ruled Nicaragua for more than 40 years until the Sandinistas removed them from power in 1979.

Founding of the FSLN

The FSLN was founded on July 19, 1961, by Carlos Fonseca Amador, Tomás Borge, and Silvio Mayorga. They were inspired by other revolutionary movements around the world, like the Cuban Revolution. They believed that the only way to remove the Somoza dictatorship was through armed struggle.

For many years, the FSLN was a small group of guerrilla fighters. They launched small military attacks but did not have much success at first.

The Road to Revolution

In 1972, a powerful earthquake destroyed much of Managua, the capital city. The Somoza government was accused of stealing much of the international aid sent to help rebuild. This made many Nicaraguans very angry and increased support for the FSLN.

In December 1974, an FSLN group took government officials hostage at a party. They demanded money and the release of Sandinista prisoners. The government agreed, and the event made the FSLN famous. One of the prisoners released was Daniel Ortega, who would later become president.

The Somoza government responded with more violence. Many FSLN members were killed, including its founder, Carlos Fonseca, in 1976.

The Final Uprising

By the late 1970s, the FSLN had split into three groups with different ideas on how to win. But in 1978, the murder of a famous newspaper editor, Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Cardenal, united the country against Somoza. People all over Nicaragua began to protest and riot.

The FSLN launched a final offensive in 1979. After months of heavy fighting, the National Guard was defeated. On July 17, 1979, Somoza fled the country. Two days later, on July 19, the FSLN army marched into Managua. The revolution was over.

The Sandinistas in Power (1979–1990)

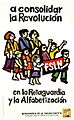

After taking power, the Sandinistas created a new government. They started many social programs. One of the most famous was the Nicaraguan Literacy Campaign. Thousands of young people went into the countryside to teach people how to read and write. This program greatly reduced illiteracy in the country.

The government also took control of land and businesses owned by the Somoza family. They gave land to many poor farmers and tried to improve conditions for workers.

The Contra War

The United States government, under President Ronald Reagan, saw the Sandinistas as a threat. The U.S. feared they would spread socialism in Latin America. In 1981, the U.S. CIA began to fund and train anti-Sandinista rebels known as the Contras.

The Contras fought a long and brutal civil war against the Sandinista government. They attacked farms, schools, and health clinics to disrupt the government's programs. The war caused thousands of deaths and destroyed Nicaragua's economy.

The U.S. also put a trade embargo on Nicaragua, which meant Americans could not buy or sell goods with the country. This hurt Nicaragua's economy even more. The conflict became famous worldwide, especially after the Iran–Contra affair, a secret plan by U.S. officials to sell weapons to Iran and give the money to the Contras.

1984 and 1990 Elections

In 1984, in the middle of the war, Nicaragua held a presidential election. Daniel Ortega and the FSLN won easily. However, some opposition parties and the U.S. government said the election was not fair.

After years of war, another election was held in 1990. This time, the FSLN lost. Violeta Barrios de Chamorro, whose husband had been murdered in 1978, was elected president. Many Nicaraguans voted for her because they hoped it would end the Contra war and the U.S. embargo. The Sandinistas peacefully handed over power.

Opposition and Return to Power

After losing the 1990 election, the FSLN was the main opposition party for 16 years. Daniel Ortega ran for president and lost in 1996 and 2001.

In 2006, Ortega won the presidential election and returned to power. Since then, he and the FSLN have won every election. However, these elections have been criticized by international groups for not being free or fair. Critics say that Ortega has taken too much control of the government and has weakened democracy in Nicaragua.

In 2018, large protests broke out against Ortega's government. The government responded with force, and hundreds of people were killed. Many opposition leaders and journalists were arrested or forced to leave the country.

Ideology and Symbols

The main ideology of the FSLN is called Sandinismo. It is based on the ideas of Augusto César Sandino and mixes socialism with Nicaraguan nationalism. It also includes ideas from liberation theology, a movement in the Roman Catholic church that focuses on helping the poor and oppressed.

The FSLN Flag

The FSLN flag has two horizontal stripes: red on top and black on the bottom. The letters "FSLN" are written in the middle. The red and black colors were used by Sandino himself during his fight against the U.S. occupation. The red stripe represents blood and sacrifice, while the black stripe represents the dark times of oppression.

Electoral history

Presidential elections

| Election | Party candidate | Votes | % | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Daniel Ortega | 735,967 | 66.97% | Elected |

| 1990 | 579.886 | 40.82% | Lost |

|

| 1996 | 664,909 | 37.83% | Lost |

|

| 2001 | 922,436 | 42.28% | Lost |

|

| 2006 | 854.316 | 38.07% | Elected |

|

| 2011 | 1,569,287 | 62.46% | Elected |

|

| 2016 | 1,806,651 | 72.44% | Elected |

|

| 2021 | 2,093,834 | 75.87% | Elected |

National Assembly elections

| Election | Party leader | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Daniel Ortega | 729,159 | 66.78% |

61 / 96

|

||

| 1990 | 579,723 | 40.84% |

39 / 92

|

|||

| 1996 | 626,178 | 36.46% |

36 / 93

|

|||

| 2001 | 915,417 | 42.6% |

39 / 92

|

|||

| 2006 | 840,851 | 37.59% |

38 / 92

|

|||

| 2011 | 1,583,199 | 60.85% |

63 / 92

|

|||

| 2016 | 1,590,316 | 65.86% |

70 / 92

|

|||

| 2021 | 2,039,717 | 74.17% |

75 / 90

|

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |