Pueblo Revolt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pueblo Revolt |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Popé see list below for others |

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400, including civilians | over 600 | ||||||

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680, also known as Popé's Rebellion, was a major uprising. It involved most of the Pueblo people against the Spanish colonizers. This happened in the area of Santa Fe de Nuevo México, which was larger than today's New Mexico. The Pueblo Revolt led to the deaths of 400 Spanish people. It also forced the remaining 2,000 Spanish settlers to leave the area. The Spanish managed to take back control of New Mexico twelve years later.

Contents

Why the Pueblo People Rebelled

For over 100 years, starting in 1540, Spanish soldiers, missionaries, and settlers came to the lands of the Pueblo people. These visits, called entradas, often led to violent fights. The Tiguex War (1540–41) was especially harsh. It involved Francisco Vázquez de Coronado's expedition against the Tiwa Native Americans.

Spanish Arrival and Harsh Rules

In 1598, Juan de Oñate arrived with many soldiers, priests, and settlers. About 40,000 Pueblo Native Americans lived in the Rio Grande valley at that time. Oñate stopped a revolt at Acoma Pueblo. He killed and enslaved hundreds of Native Americans. He also gave severe punishments to the men. This event, known as the Acoma Massacre, caused great fear and anger.

Spanish rules about treating native people fairly were often ignored. After 1598, Pueblo people had to give tribute to the colonists. This included labor, corn, and textiles. Spanish settlers also set up Encomiendas along the Rio Grande. These systems took over Pueblo farmlands and water. They also forced the Pueblo people to work very hard.

Attacks on Pueblo Culture and Religion

The Spanish also attacked the Pueblo people's traditional religion. Franciscan priests tried to set up religious governments in many Pueblo villages. They wanted to convert the Pueblo people to Christianity.

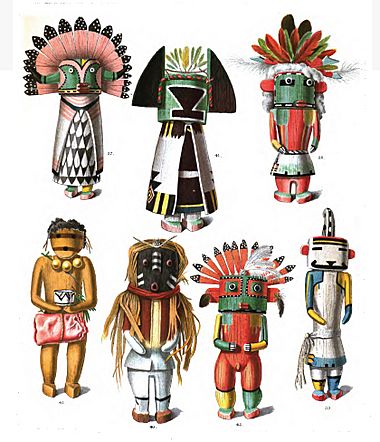

A priest named Fray Alonso de Posada (in New Mexico from 1656–1665) banned Kachina dances. These were very important to the Pueblo religion. He ordered missionaries to burn their masks and other religious items. The priests also stopped the use of special plants in ceremonies. Some Spanish officials tried to protect the Pueblo people. But they were often accused of heresy and put on trial.

Drought and Arrests

In the 1670s, a severe drought hit the region. This caused a famine among the Pueblo people. Attacks by the Apache also increased. Spanish and Pueblo soldiers could not stop these raids.

Tensions grew very high by 1675. Governor Juan Francisco Treviño ordered the arrest of 47 Pueblo medicine men. He accused them of practicing "sorcery". Four of these men were sentenced to death. The others were publicly whipped and sent to prison.

When Pueblo leaders heard this, they marched to Santa Fe. The prisoners were held there. Many Spanish soldiers were away fighting the Apache. So, Governor Treviño had to agree to release the prisoners. One of the released men was a San Juan native named "Popé".

The Rebellion Begins

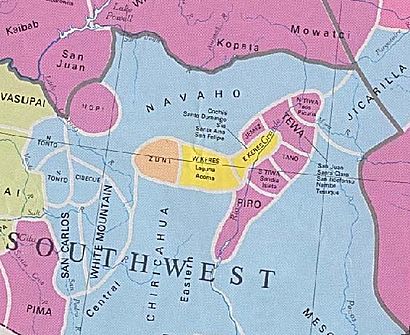

After his release, Popé and other Pueblo leaders began planning the revolt. Popé moved to Taos Pueblo, far from Santa Fe. For five years, he worked to get support from the 46 Pueblo towns. He gained the support of many Pueblo groups. These included the Northern Tiwa, Tewa, Towa, Tano, and Keres-speaking Pueblos. The Pecos, Zuni, and Hopi Pueblos also joined.

Some Pueblos did not join the revolt. These were the four southern Tiwa towns near Santa Fe and the Piro Pueblos. These groups were more connected to Spanish culture. The Spanish population was about 2,400 people. This included mixed-blood people and native servants. They were spread out thinly across the region. Santa Fe was the only real town. The Spanish could only gather about 170 armed men. The Pueblos who joined the revolt likely had 2,000 or more adult men. They were skilled with native weapons like the bow and arrow. Some Apache and Navajo people might have also helped in the revolt.

Popé's Plan

Popé promised that if the Spanish were killed or driven out, the old Pueblo gods would bring health and good times. Popé's plan was for each Pueblo to rise up and kill the Spanish in their area. Then, they would all march to Santa Fe to get rid of the remaining Spanish. The revolt was set for August 11, 1680. Popé sent runners to all the Pueblos. They carried knotted cords. Each morning, a leader would untie one knot. When the last knot was untied, it would be the signal to attack.

However, on August 9, the Spanish learned about the plan. Southern Tiwa leaders warned them. The Spanish captured two young men from Tesuque Pueblo. These youths were carrying the knotted cords. They were questioned to find out the meaning of the cords.

The Uprising

Because of this, Popé ordered the revolt to start a day early. The Hopi pueblos, being far away, did not get the early warning. They followed the original schedule.

On August 10, the Puebloans rose up. They stole Spanish horses to stop them from escaping. They blocked roads to Santa Fe and raided Spanish settlements. A total of 400 people were killed. This included men, women, children, and 21 of the 33 Franciscan priests. In the Hopi area, churches were destroyed. The priests there were also killed.

Survivors fled to Santa Fe and Isleta Pueblo. Isleta was one of the Pueblos that did not join the rebellion. By August 13, all Spanish settlements in New Mexico were destroyed. Santa Fe was surrounded. The Puebloans cut off the city's water supply.

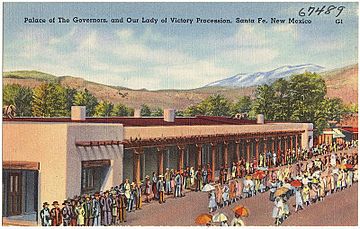

On August 21, Governor Antonio de Otermín was trapped in the Palace of the Governors. In desperation, he led his men out of the palace. They fought the Puebloans, forcing them to retreat. Otermín then led the Spanish out of Santa Fe. They marched south along the Rio Grande towards El Paso del Norte. The Puebloans followed but did not attack. The Spanish survivors from Isleta had also retreated south. On September 6, the two groups met. There were 1,946 survivors, including about 500 Native American servants. They were escorted to El Paso. The Puebloans did not stop them from leaving New Mexico.

New Mexico Under Pueblo Rule

With the Spanish gone, the Puebloans controlled New Mexico. Popé is a mysterious figure in history. There are many stories about what happened to him after the revolt. Later, Pueblo people told the Spanish different things. This was probably because they disliked Popé or wanted to please the Spanish.

Popé and his two main helpers, Alonso Catiti and Luis Tupatu, traveled around. They ordered everyone to return "to the state of their antiquity." This meant destroying all crosses, churches, and Christian images. People were told to cleanse themselves in ritual baths. They had to use their Pueblo names. They also had to get rid of all signs of Spanish culture. This included Spanish livestock and fruit trees. It was said that Popé even forbade planting wheat and barley. He also told natives married in the Catholic Church to leave their wives and marry in the old native way.

The Pueblo people did not have a history of being politically united. Popé was a very strict leader. Each pueblo was self-governing. Some, or all, of them seemed to resist Popé's demands. The perfect world Popé had promised did not happen. The drought continued, ruining crops. Attacks by Apache and Navajo tribes also increased. However, at first, the Puebloans were united in keeping the Spanish away.

Popé was removed as leader about a year after the revolt. He then disappeared from history. He is thought to have died shortly before the Spanish returned in 1692.

Spanish Try to Return

In November 1681, Antonio de Otermín tried to return to New Mexico. He gathered 146 Spanish soldiers and the same number of native soldiers in El Paso. They marched north along the Rio Grande. He first found the Piro pueblos empty and their churches destroyed. At Isleta pueblo, he fought a short battle. Then, he accepted their surrender.

While at Isleta, he sent soldiers to re-establish Spanish rule. But the Puebloans pretended to surrender. They were gathering a large force to fight Otermín. With the threat of a Puebloan attack growing, Otermín decided to return to El Paso on January 1, 1682. He burned pueblos and took the people of Isleta with him. The first Spanish attempt to regain control of New Mexico had failed.

Some Isleta people later returned to New Mexico. Others stayed in El Paso, living in the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo. The Piro also moved to El Paso. They lived among the Spanish.

The Spanish were never able to convince some Puebloans to rejoin them. For example, the Hopi remained free from Spanish control. The Spanish tried for peace treaties and trade agreements, but they failed. For some Puebloans, the Revolt successfully drove away Spanish influence.

The Spanish Reconquest

The Spanish decided to return to New Mexico for a few reasons. They feared French expansion into the Mississippi valley. They also wanted to create a defense against aggressive nomadic tribes.

In August 1692, Diego de Vargas marched to Santa Fe. He was joined by a converted Zia war captain, Bartolomé de Ojeda. De Vargas had only sixty soldiers, one hundred native soldiers, seven cannons, and one Franciscan priest. He arrived at Santa Fe on September 13. He promised the 1,000 Pueblo people there forgiveness and protection. This was if they would promise loyalty to the King of Spain and return to Christianity. After some discussion, the Pueblo people first refused. But after much convincing, they finally agreed to peace.

On September 14, 1692, de Vargas officially claimed the land again. He wrote happily that it was the thirteenth town he had taken back for God and King. Over the next month, de Vargas visited other Pueblos. They also agreed to Spanish rule.

Renewed Conflict and Lasting Impact

The 1692 agreement was peaceful. But in the years that followed, de Vargas became stricter. The Pueblo people became more defiant. De Vargas returned to Mexico and gathered about 800 people. This included 100 soldiers. He came back to Santa Fe on December 16, 1693. This time, 70 Pueblo warriors and 400 family members inside the town fought his entry. De Vargas and his forces quickly recaptured the town. The 70 Pueblo warriors were killed on December 30. Their surviving families (about 400 women and children) were made to work for the Spanish colonists for ten years.

In 1696, people from fourteen pueblos tried a second organized revolt. Five missionaries and thirty-four settlers were killed. They used weapons the Spanish had traded to them. De Vargas's response was harsh and long-lasting. By the end of the century, the last resisting Pueblo town had surrendered. The Spanish reconquest was mostly complete. However, many Pueblos fled New Mexico. They joined the Apache or Navajo, or tried to resettle on the Great Plains. One of their settlements was found in Kansas.

Even though the independence of many pueblos was short-lived, the Pueblo Revolt was a success in some ways. It gave the Pueblo people more freedom from Spanish efforts to destroy their culture and religion. After the reconquest, the Spanish gave large land grants to each Pueblo. They also appointed a public defender to protect the rights of Native Americans. The Franciscan priests who returned to New Mexico did not try to force their religion on the Pueblo people again. The Pueblo people continued to practice their traditional religion.

In the Arts

The 1994 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode "Journey's End" mentions the Pueblo Revolt. It talks about ancestors of different characters being involved.

In 1995, in Albuquerque, a play called Casi Hermanos was produced. It was written by Ramon Flores and James Lujan. The play showed events leading up to the Pueblo Revolt. It was inspired by stories of two half-brothers who fought on opposite sides.

A statue of Po'Pay by sculptor Cliff Fragua was added to the National Statuary Hall Collection in the US Capitol Building in 2005. It is one of New Mexico's two statues there.

In 2005, in Los Angeles, Native Voices at the Autry produced Kino and Teresa. This play was an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. It was written by Taos Pueblo playwright James Lujan. The story is set five years after the Spanish Reconquest of 1692. It shows how both sides learned to live together. This helped form the culture of present-day New Mexico.

In 2010, students from Santa Fe Indian School created a spoken word piece. It told the story of the Pueblo Revolt, called "Po'pay". The team performed in New Mexico and the US. They also performed in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

Pueblo Revolt Leaders and Their Home Pueblos

- Ku-htihth (Cochiti): Antonio Malacate

- Galisteo (Galisteo): Juan El Tano

- Walatowa (Jemez): Luis Conixu

- Nambé (Nambé): Diego Xenome

- Welai (Picuris): Luis Tupatu (Ciervo Blanco)

- Powhogeh (San Ildefonso): Francisco El Ollito and Nicolas de la Cruz Jonv

- Ohkay (San Juan): Po'pay and Tagu

- San Lazaro: Antonio Bolsas and Cristobal Yope

- Khapo (Santa Clara): Domingo Naranjo and Cajete

- Kewa (Santo Domingo): Alonzo Catiti

- Teotho (Taos): El Saca

- Tehsugeh (Tesuque): Domingo Romero

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de los indios de Nuevo México para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de los indios de Nuevo México para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |