Spanish American Enlightenment facts for kids

The ideas of the Spanish Enlightenment were about using reason, science, and practical thinking. They came from France to the New World in the 1700s, after the Bourbon family became kings in Spain.

In Spanish America, these new ideas influenced educated people in big cities like Mexico City, Lima, and Guatemala. These cities had universities that were already open to new ways of thinking, even before the Bourbons took power. The University of San Carlos Guatemala, founded in 1676, is a good example.

Contents

History of Enlightenment Ideas

In Spanish America, just like in Spain, the Enlightenment sometimes went against the power of the church. However, many priests actually supported science and scientific thinking. Some even supported both the Enlightenment and independence from Spain. Books by Enlightenment thinkers were read in Spanish America, even though the Inquisition (a powerful church court) tried to ban them.

The Jesuits were very important in bringing new ideas to Spanish America. After they were expelled in 1767, the Franciscans continued to explore these thoughts. Many priests, like Mexican priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, owned these books. Hidalgo's free thinking even caused him to lose his job as a seminary leader.

Scientists and Thinkers

Even in the 1600s, priests were involved in science. Famous examples include Mexican thinker Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora and the amazing nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. In the 1700s, many priests born in Spain and America practiced science.

One important scientist was José Celestino Mutis in New Granada (modern-day Colombia). He led a royal expedition to study plants. Mutis taught Francisco José de Caldas. In Peru, Hipólito Unanue, a doctor and priest, wrote for a Peruvian newspaper called Mercurio Peruano.

Another key figure was Mexican priest José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez. He started important newspapers that shared new scientific discoveries, including his own. When the famous scientist Alexander von Humboldt visited Spanish America, he met Mutis and Caldas. He also read Alzate's works and was very impressed by the level of science in the region.

Kings, Church, and New Ideas

Two main types of political ideas were popular in Spanish America. One was enlightened despotism, where a ruler had total power but used it to improve society. The other was constitutionalism, which supported governments with rules and laws.

There were also disagreements among priests. Some supported regalism, meaning the king should have power over the Catholic Church. Others supported ultramontanism, meaning the Pope should have power over kings.

The Spanish king wanted more control over the Catholic Church. So, in 1767, he expelled the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) from Spain and its colonies. The Jesuits were very loyal to the Pope. They were successful in their missions to native peoples and ran many schools where Enlightenment ideas were taught. They also owned many profitable farms called haciendas. Because they were so loyal to the Pope and successful, the king saw them as a threat.

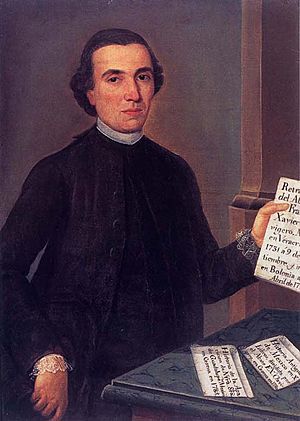

Expelling the Jesuits was a big blow to wealthy American-born Spanish families. Many of their sons were educated by Jesuits or were Jesuits themselves. This event made many American-born Spaniards feel less loyal to the Spanish king. One important exiled Jesuit was Francisco Javier Clavijero. He wrote a major history of Mexico, showing its roots in ancient native civilizations. This helped create an idea of Mexico as separate from Spain.

The Spanish king also tried to limit the special rights of the Catholic Church. This included the fuero eclesiástico, which allowed priests to be judged by church courts instead of royal courts. This right had given priests a lot of power and respect. Parish priests were often the only Europeans in native villages, holding both religious and political power.

In late colonial Mexico, a liberal bishop named Manuel Abad y Queipo wanted social and economic changes. However, he strongly opposed Father Hidalgo's uprising for independence in 1810. Abad y Queipo shared his ideas about New Spain with Alexander von Humboldt, and these ideas appeared in Humboldt's famous book, Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain.

Progress and New Institutions

Another development in Spanish America was the creation of economic societies. These groups of important men aimed to improve the local economy using science. They also discussed political issues, especially as the king's policies started to favor Spain more than the colonies.

The king also founded new institutions to promote science, economy, and culture. In Mexico, the College of Mines was established in 1792. It was led by Spanish expert Fausto Elhuyar. Its goal was to train experts for silver mining, which was the most profitable industry in the empire.

Art and architecture also changed with Enlightenment ideas. The Academy of San Carlos was founded in 1781 as a school for engraving. Later, it became the Royal Academy of the Three Noble Arts of San Carlos. Miguel Cabrera was a key member.

Buildings like the Palacio de Minería in Mexico City, the hospicio in Guadalajara, and the cathedral in Buenos Aires were designed in the Neoclassical style. This style used clean lines and less decoration, unlike the more ornate Baroque style. The Baroque style was popular because it was easy to understand and offered comfort. But the Neoclassical academies of the 1700s disliked this popularity.

The growth of scientific ideas, like Carl Linnaeus's way of classifying living things, might have led to new types of paintings. These were called casta paintings. They showed different racial mixtures and social ranks in late 1700s Mexico.

Changes in Daily Life

The king also tried to control popular parts of "Baroque" Catholicism. For example, he stopped burials inside churches and churchyards for public health reasons. He successfully stopped Carnival celebrations in Mexico and tried to reduce popular religious practices like processions.

The king also stopped supporting secular entertainments like bullfighting. Theater plays started to have educational and non-religious themes instead of religious ones.

See also

In Spanish: Ilustración hispanoamericana para niños

In Spanish: Ilustración hispanoamericana para niños

- Spanish Empire

- Spanish Enlightenment

- Historiography of Colonial Spanish America

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |