Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest facts for kids

Long ago, during the Age of Exploration, the Spanish Empire sent many ships to the Pacific Northwest of North America. Spain believed these lands belonged to them. This idea started in 1493 with a special paper from the Pope, and then with a treaty in 1494 called the Treaty of Tordesillas. In 1513, a Spanish explorer named Vasco Núñez de Balboa saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time. He then claimed all the lands next to this ocean for the Spanish King and Queen.

However, Spain didn't start building towns or settlements north of what is now Mexico until the 1700s. They first settled the northern coast of Las Californias. By the mid-1700s, other countries like the British and Russians also wanted these lands. They started setting up places to trade furs and build small towns.

To protect their claims, King Charles III of Spain and the kings who came after him sent several trips from New Spain (which was like a Spanish colony in North America) to what is now Canada and Alaska. These trips happened between 1774 and 1793. Even with all this effort, Spain eventually gave up its claims in this region. In 1819, they gave these lands to the American government in a deal called the Adams-Onís Treaty.

Contents

- Early Spanish Voyages to the Pacific Northwest

- Spanish Presence in Nootka Sound

- Spanish Legacy in the Pacific Northwest

- See also

Early Spanish Voyages to the Pacific Northwest

Spanish explorers made several important journeys to the Pacific Northwest. These trips helped them map the coast and claim new lands.

1774: The First Voyage by Pérez

The first Spanish ship to explore the Pacific Northwest was the Santiago, led by Juan José Pérez Hernández. His goal was to reach Alaska. But the ship turned back when it reached Haida Gwaii, which is now part of Canada. Pérez and his crew of 86 were the first known Europeans to visit this part of the Pacific Northwest.

1775: Heceta and Bodega y Quadra's Journey

In 1775, a second voyage began with 90 men. Lieutenant Bruno de Heceta led the Santiago. They left San Blas, Nayarit with orders to claim the entire Northwestern Pacific Coast for Spain. A smaller ship, the Sonora, joined them. It was led by Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. The Sonora was only about 36-foot (11 m) long and had 16 crew members. Its job was to explore the coast closely and make maps. This way, the expedition could officially claim the lands north of New Spain.

Another ship, the San Carlos, also sailed with them. Its first commander got sick, so Juan de Ayala took over. The three ships sailed together to Monterey Bay in Alta California. Ayala's mission was to explore the Golden Gate strait. Heceta and Bodega y Quadra continued north. Ayala and his crew on the San Carlos were the first Europeans known to enter San Francisco Bay.

The Santiago and Sonora kept sailing north. They reached Point Grenville, which Heceta named "Point of the Martyrs." This was because local Quinault Indians attacked them there. On July 29, 1775, the two ships separated. Many of Heceta's crew on the Santiago were sick with scurvy. So, Heceta decided to return to San Blas. On his way back, he found the mouth of the Columbia River, which is now between Oregon and Washington. Juan Pérez, who was helping Heceta navigate, died during this trip.

Bodega y Quadra continued north in the Sonora as planned. He reached as far as 59° north latitude on August 15. He then entered Sitka Sound near the town of Sitka, Alaska. On his way back south, Bodega y Quadra found and explored part of Bucareli Bay on the west side of Prince of Wales Island. During his journey, the Spanish claimed many places and gave them names. For example, they named Bucareli Bay and Mount San Jacinto. Three years later, the British explorer James Cook renamed Mount San Jacinto to Mount Edgecumbe.

1779: Arteaga and Bodega y Quadra's Exploration

A third voyage happened in 1779. It was led by Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán with two armed ships called corvettes: the Favorita (Arteaga's ship) and the Princesa (Bodega y Quadra's ship). The goal of this trip was to see how far the Russians had explored in Alaska. They also wanted to find a Northwest Passage (a sea route through North America). Spain also hoped to capture James Cook if they found him in their waters. Spain knew about Cook's explorations in the Pacific Northwest in 1778.

In June 1779, while Arteaga and Bodega y Quadra were on their journey, Spain joined the American Revolutionary War as a friend of France. This started a war between Spain and Britain. This war lasted until 1783. Arteaga and Bodega y Quadra did not find Cook. He had been killed in Hawaii in February 1779.

During their voyage, Arteaga and Bodega y Quadra carefully mapped Bucareli Bay. Then they went north to Port Etches on Hinchinbrook Island. They entered Prince William Sound and reached 61° latitude. This was the farthest north any Spanish expedition had gone in Alaska. They also explored Cook Inlet and the Kenai Peninsula. On August 2, they held a ceremony to claim the land at a place now called Port Chatham. Because many crew members were sick, Arteaga returned to California without finding the Russians.

The crews on both ships faced many difficulties, like not having enough food and getting scurvy. On September 8, the ships met again and sailed south to San Blas. Usually, the Spanish kept their discoveries secret. But the 1779 voyage became widely known. A copy of their map was published in 1798. Also, the journal of Francisco Antonio Mourelle (Bodega y Quadra's pilot) was published in London in 1798.

After these three trips to Alaska in five years, Spain stopped sending expeditions to the Pacific Northwest until 1788. This was after the Treaty of Paris ended the war between Spain and Britain. During the war, Spain focused its efforts on the Philippines. Support for Alta California, which relied on San Blas, was very low. By 1786, Alta California could mostly support itself. Peace with Britain was restored, making new trips to Alaska possible.

1788: Martínez and Haro's Journey

In March 1788, two ships sailed north from San Blas to check on Russian activities. Esteban José Martínez Fernández y Martínez de la Sierra commanded the expedition on the Princesa. The San Carlos was led by Gonzalo López de Haro, with José María Narváez as his pilot. The ships reached Prince William Sound in May. They found signs of Russian fur trading and sailed west. In June, Haro reached Kodiak Island. There, he learned from the local people that a Russian outpost was nearby.

On June 30, 1788, Haro sent Narváez in a small boat to find the Russian outpost at Three Saints Bay. Narváez found it and became the first Spaniard to meet a large group of Russians in Alaska. Narváez brought the Russian commander, Evstratii Delarov, to meet Haro on the San Carlos. Delarov gave Narváez a Russian map of the Alaskan coast. He also showed where seven Russian outposts were, with almost 500 men. Delarov also told Narváez that the Russians planned to take over Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

After this meeting, Haro sailed east and met Martínez at Sitkinak Island. Using the information from Delarov, the expedition sailed to Unalaska Island. There was a large Russian outpost there, also called Unalaska, led by Potap Kuzmich Zaikov. Martínez arrived on July 29, and Haro on August 4. Zaikov gave Martínez three maps of the Aleutian Islands. He also confirmed that the Russians planned to take Nootka Sound the next year. Zaikov said two Russian ships were already on their way, and a third would sail to Nootka Sound. He was talking about an expedition by Joseph Billings in 1789, but he made its mission sound much bigger than it was. The visit to Unalaska was the farthest west the Spanish explorers went in Alaska.

The Spanish expedition left Unalaska on August 18, 1788, heading south for California and Mexico. Martínez and Haro started arguing more and more. Within three days, the ships separated and sailed south on their own. Martínez had allowed this but told Haro to meet him in Monterey, California. But during the trip south, Haro, with help from Narváez and other pilots, said his ship was no longer under Martínez's command. They sailed back to San Blas on their own, arriving on October 22, 1788. Martínez waited a month in Monterey for Haro. He arrived in San Blas in December. There, he faced accusations of bad leadership. But he soon got back into favor. He was put in charge of a new trip to take Nootka Sound before the Russians did. This trip happened in 1789 and led to the Nootka Crisis.

Spanish Presence in Nootka Sound

Spain decided to establish a permanent base at Nootka Sound. This was important because of the Nootka Crisis, a big international problem that almost led to war between Spain and Britain.

1789: Taking Nootka Sound

After the 1788 trip to Alaska, Martínez and Haro were told to take over Nootka Sound before the Russians did. Events at Nootka Sound in 1789 caused the Nootka Crisis. During the summer of 1789, Martínez sent José María Narváez to explore the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Narváez found that the Strait of Juan de Fuca was a large inlet that looked promising for more exploration. By the end of the year, Martínez left Nootka Sound.

1790: Building a Spanish Base

Three ships sailed to Nootka Sound. Francisco de Eliza was the main commander. They built the first Spanish settlement in what is now British Columbia, called Santa Cruz de Nuca. They also built Fort San Miguel, which was protected by soldiers. After settling in, Eliza sent Salvador Fidalgo and Manuel Quimper on new exploration trips. Fidalgo went north, and Quimper went south.

1790: Fidalgo's Alaskan Voyage

In 1790, Spanish explorer Salvador Fidalgo sailed the San Carlos to Alaska. He visited and named Cordova Bay and Port Valdez in Prince William Sound. He performed ceremonies to claim these places for Spain. Fidalgo entered Cook Inlet and found a Russian outpost. He continued west to Kodiak Island and saw another Russian outpost. Fidalgo then went to a Russian settlement at Alexandrovsk (now called Nanwalek, Alaska). There, he again claimed the area for Spain with a formal ceremony.

1790: Quimper Explores the Strait of Juan de Fuca

In 1790, Manuel Quimper, with officers López de Haro and Juan Carrasco, sailed the Princesa Real into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. They were following up on Narváez's trip from the year before. Quimper sailed to the eastern end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. He discovered the San Juan Islands and many other straits and inlets. He had limited time, so he had to return to Nootka without fully exploring all the promising areas. Strong winds made it impossible to sail his small ship back to Nootka, so Quimper went south to San Blas instead.

1791: Eliza Continues Exploring

In 1791, Francisco de Eliza was ordered to keep exploring the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Two ships were part of this trip. Eliza sailed on the San Carlos. Narváez sailed on the Santa Saturnina. During this journey, the Strait of Georgia was discovered. Narváez quickly explored most of it. Eliza sailed the San Carlos back to Nootka Sound. But the Santa Saturnina, under Carrasco, could not reach Nootka. Instead, it sailed south to Monterey and San Blas. In Monterey, Carrasco met Alejandro Malaspina and told him about finding the Strait of Georgia. This meeting directly led to the 1792 voyage of Galiano and Valdés.

1789-1794: The Malaspina Expedition

The King of Spain gave Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra command of a scientific expedition around the world. They had two ships, the Descubierta and Atrevida. One of the king's orders was to look for a possible Northwest Passage. The expedition also had to search for gold, valuable stones, and any American, British, or Russian settlements along the northwest coast. They arrived in Alaska in 1791. Malaspina and Bustamante mapped the coast all the way to Prince William Sound. At Yakutat Bay, the expedition met the Tlingit people. Spanish experts studied the tribe. They wrote down information about their customs, language, economy, ways of fighting, and burial practices. Artists on the trip drew pictures of tribal members and scenes of Tlingit daily life. The Malaspina Glacier, between Yakutat Bay and Icy Bay, was later named after Alessandro Malaspina.

In 1792, Dionisio Alcalá Galiano on the Sutil and Cayetano Valdés y Flores on the Mexicana sailed from San Blas to Nootka Sound. Then, they sailed all the way around Vancouver Island. A report about Galiano and Valdés's trip was published in Spain and widely shared. This made their voyage seem more important than Malaspina's, who became a political prisoner soon after returning to Spain.

1792: Caamaño's Detailed Survey

Jacinto Caamaño, commander of the ship Aránzazu, sailed to Bucareli Bay in 1792. Juan Pantoja y Arriaga was his pilot. Caamaño made a very detailed map of the coast south to Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island. By 1792, many parts of the coast had already been visited by European explorers. But some areas had been missed, like the southern part of Prince of Wales Island. Several of the names Caamaño gave to places in the area are still used today. These include Cordova Bay, Revillagigedo Channel, Bocas de Quadra, and Zayas Island (named after his second pilot, Juan Zayas) in what is now called Caamaño Passage.

No report about Caamaño's voyage was published for a long time. So, his discoveries remained unknown to many. However, George Vancouver apparently met Caamaño and got copies of his maps, especially of areas north of Dixon Entrance. Vancouver later used some of Caamaño's place names in his own maps.

1793: Eliza and Martínez y Zayas's Coastal Survey

In 1793, Francisco de Eliza and Juan Martínez y Zayas mapped the coast between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and San Francisco Bay. They also explored the mouth of the Columbia River.

Spanish Legacy in the Pacific Northwest

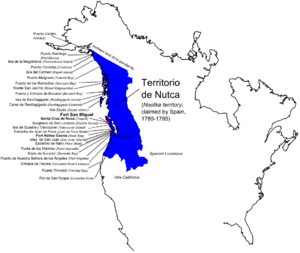

After all these trips, Spain claimed the explored areas as part of New Spain. This specific region was known as "Territorio de Nautica." However, because of the Nootka Crisis with Britain in 1789 and the agreements that followed, Spain decided to step back from the North Pacific. Later, in the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, Spain gave its claims in the region to the United States.

Today, Spain's history in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest lives on through many place names. For example, you can find Malaspina Glacier, Revillagigedo Island, and the towns of Valdez and Cordova.

See also

In Spanish: Expediciones de España en el Pacífico Noroeste para niños

In Spanish: Expediciones de España en el Pacífico Noroeste para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |