Malaspina Expedition facts for kids

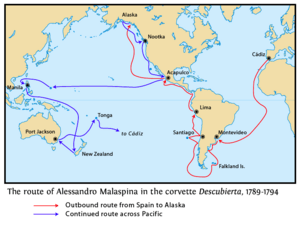

The Malaspina Expedition (1789–1794) was a big five-year journey by sea for scientific exploration. It was led by Alejandro Malaspina and José de Bustamante y Guerra. Even though it's called the Malaspina Expedition, Malaspina always wanted Bustamante to get equal credit for leading it.

The Spanish government paid for this expedition. Its main goal was to collect scientific information, much like the famous voyages of James Cook and Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse. The scientists on board gathered a huge amount of data, even more than Cook's expedition. However, when Malaspina returned, he was put in jail because he was involved in a plan against the government. Because of this, most of the expedition's findings and collections were kept secret and weren't published until much later, in the late 1800s.

Contents

Getting Ready for the Journey

Before this big trip, Malaspina had already sailed around the world for a trading company from 1786 to 1788. During that journey, he visited Concepcion in Chile. The governor there, Ambrose O'Higgins, had suggested that Spain should send an expedition to the Pacific Ocean, like the ones led by Lapérouse and Cook.

After Malaspina returned to Spain, he and José de Bustamante suggested a similar plan. The Spanish government quickly agreed in October 1788. They were also encouraged by news that Russia was planning an expedition to the North Pacific. Russia wanted to claim land in North America that Spain also claimed, like Nootka Sound.

Spain had a very large budget for science at that time. In the last 40 years of the 1700s, many scientific trips had explored the Spanish Empire. These trips collected a huge number of plants from the Americas. They saw the New World as a giant laboratory full of new things to study.

The Spanish king, Charles III, loved science. He quickly approved the expedition, but he died two months later and never saw its results.

The Spanish government was also very interested in the Pacific Ocean because many of its colonies were there. These included most of the American Pacific coast, the Philippines, and islands like Guam.

Two special ships were built for the expedition by Tómas Muñoz, under Malaspina's guidance. They were named Descubierta and Atrevida. These names were chosen to honor James Cook's ships, Resolution and Discovery. Both ships were launched on April 8, 1789. Malaspina commanded Descubierta, and Bustamante commanded Atrevida.

The expedition included the best astronomers and mapmakers from the Spanish Navy. Juan Gutiérrez de la Concha led them, and Felipe Bauza was the main mapmaker. Many other scientists and artists joined too. These included painting master José del Pozo, artists José Guío, Fernando Brambila and Giovanni Ravenet, cartoonist Tomás de Suria, and botanists Luis Née, Antonio Pineda and Thaddäus Haenke.

The Journey Begins

The ships Atrevida and Descubierta left Cádiz, Spain, on July 30, 1789. After a short stop in the Canary Islands, they sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to South America. They went down to the Río de la Plata and stopped in Montevideo and Buenos Aires. There, they wrote a report about the political situation in the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

Next, they sailed to the Falkland Islands. From there, they headed towards Cape Horn, entering the Pacific Ocean on November 13. They stopped at Talcahuano, the port of Concepción in Chile, and then at Valparaíso, the port of Santiago.

As they continued north, Bustamante mapped the coast. Malaspina sailed to the Juan Fernández Islands to check their exact location. The two ships met again at Callao, the port of Lima, in Peru. Here, they studied the political situation in the Viceroyalty of Peru. The expedition then kept sailing north, mapping the coast all the way to Acapulco, Mexico. A group of officers was sent to Mexico City to look at old records and learn about the political situation in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

While in Mexico, the expedition received a new order from the new king, Charles IV. He told them to search for a Northwest Passage, a rumored sea route through North America. This meant Malaspina had to change his plans. He had wanted to sail to Hawaii, Kamchatka, and the Pacific Northwest. Instead, he sailed directly from Acapulco to Yakutat Bay, Alaska.

At Yakutat Bay, they didn't find the passage, but they carefully mapped the Alaskan coast. They met the Tlingit people there. Spanish scholars studied their way of life, language, and customs. Artists drew portraits of the Tlingit people and scenes from their daily lives. A large glacier in Alaska was later named Malaspina Glacier after him.

Malaspina knew that Captain Cook had already explored the coast west of Prince William Sound and found no passage. So, Malaspina stopped his search there and sailed to the Spanish outpost at Nootka Sound on Vancouver Island.

The expedition spent a month at Nootka Sound. They studied the Nuu-chah-nulth people (also called Nootka peoples). When Malaspina arrived, the relationship between the Spanish and the Nootkas was not good. Malaspina and his crew worked hard to improve it, which was one of their main goals. They gave generous gifts from their ships, which helped build friendship. Gaining the trust of Chief Maquinna, a powerful leader, was very important. His friendship helped strengthen Spain's claim to Nootka Sound. The Spanish government wanted the Nootka people to formally agree that the land where the Spanish outpost stood was given freely. This was important for Spain's discussions with Britain about Nootka Sound. Malaspina succeeded in getting this agreement from Chief Maquinna.

Besides working with the Nootkas, the expedition also made detailed maps of Nootka Sound. They explored unknown waterways. They also linked their maps to those made by Captain Cook, which helped compare Spanish and British charts. Scientists studied plants and even tried to make a type of beer from pine needles. They hoped this beer would help prevent scurvy, a disease caused by lack of Vitamin C. The ships also took on fresh water and wood and gave the Spanish outpost useful supplies like medicine and tools.

After leaving Nootka Sound, the ships sailed south. They stopped at the Spanish settlement in Monterey, California, before returning to Mexico.

In 1792, back in Mexico, Malaspina sent two smaller ships, called schooners, to explore the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Strait of Georgia in more detail. These ships were the Sutíl, led by Dionisio Alcalá Galiano, and the Mexicana, led by Cayetano Valdés y Flores. Both were officers from Malaspina's expedition.

Later in 1792, Malaspina's expedition sailed from Mexico across the Pacific Ocean. They made a brief stop at Guam before reaching the Philippines, where they stayed for several months, mainly in Manila. During this time, Malaspina sent Bustamante in the Atrevida to Macau, China.

After Bustamante returned, the expedition left the Philippines and sailed to New Zealand. They explored Doubtful Sound on the South Island. They mapped its entrance and lower parts. Even though they stayed for only one day, they left behind Spanish place names like Febrero Point (named after February, the month of their visit), Bauza Island (after their mapmaker), and Marcaciones Point (Observation Point).

Then Malaspina sailed to Port Jackson (Sydney) in New South Wales (Australia). This British settlement had been started in 1788. During their visit to Sydney Cove in March–April 1793, the botanist Thaddäus Haenke studied the local plants and animals. Twelve drawings were made by the expedition members during this visit. These drawings are very important because they show what the settlement looked like in its early years. They also include the only pictures of the convict settlers from that time.

The Spanish government was worried about the new British colony in Sydney. They thought it could be a threat to Spain's colonies in the Pacific, both for trade and in case of war. Malaspina agreed with this warning. However, he also saw a chance for peaceful trade. He suggested that Spain could sell food and livestock from Chile to the new colony. He thought this would be good for trade and help calm relations with their "lively, turbulent, and even insolent neighbor."

Returning east across the Pacific Ocean, the expedition spent a month at Vava'u, a group of islands in northern Tonga. From there, they sailed to Callao, Peru, and then Talcahuanco, Chile. They carefully mapped the fjords of southern Chile before sailing around Cape Horn. Then they surveyed the Falkland Islands and the coast of Patagonia, stopping again at Montevideo.

From Montevideo, Malaspina took a long route through the central Atlantic Ocean back to Spain. He arrived in Cádiz on September 21, 1794. He had spent 62 months at sea.

Discoveries and Achievements

During its five years, the Malaspina Expedition mapped the western coast of America with amazing accuracy. They measured the height of Mount Saint Elias in Alaska and explored huge glaciers, including the Malaspina Glacier, which was named after him. Malaspina also showed that a Panama Canal could be built and even drew up plans for it.

One of the expedition's greatest successes was that almost no one got scurvy. Malaspina's doctor, Pedro González, was sure that fresh oranges and lemons were key to preventing the disease. Only one small outbreak happened during a 56-day trip across the open sea. Five sailors showed symptoms, but after three days at Guam, they were all healthy again. While James Cook had also made progress against scurvy, other captains found it hard to copy his success. It was known that citrus fruits helped, but it was hard to store them on ships for long trips without losing their helpful vitamins. Spain's many colonies and ports made it easier to get fresh fruit.

The expedition also made many experiments about the weight of objects in different parts of the world. These experiments helped scientists learn more about the shape of our planet and could even help create a fixed, general way to measure things (like the metric system). They also collected information about the people they met, learning about their cultures and how they lived. The expedition was peaceful, and the local tribes were happy to meet the navigators, who gave them tools and taught them new skills. It was amazing that almost all the crew members returned safely, with very few losing their lives, especially considering the long journey through hot climates.

What Happened Next

Sadly, Malaspina got involved in a plan to remove Spain's Prime Minister, Godoy. He was arrested on November 23, 1795, for plotting against the state. After a trial, King Charles IV ordered Malaspina to lose his rank and be put in prison in the San Antón fortress in La Coruña, Spain. He stayed there from 1796 to 1802. When he was finally freed, he was not allowed to return to Spain.

It was thought that the expedition's reports would fill seven large books. Publishing them would have cost a lot of money. José de Bustamante tried to get the journals and reports published, but Spain's government didn't have enough money, especially during the difficult years after Malaspina's arrest. Some parts were published at the time, but it took 200 years for most of the expedition's records to be made public.

Many of the documents from the expedition are still scattered in different archives today. Some are even lost. Alexander von Humboldt, a famous explorer who admired Malaspina, once wrote that Malaspina was "more famous for his misfortunes than for his discoveries."

The notes made by the expedition's botanist, Luis Née, during his visit to Port Jackson in 1793 were published in 1800. Dionisio Alcalá Galiano's journal about his survey of the straits near Vancouver Island was published in 1802, but Malaspina's name was removed from it. In 1809, José Espinosa y Tello published the astronomical observations from the expedition, which also included a shorter story of the voyage. This story was translated into Russian and published in 1815. Malaspina's own journal was first published in Russian between 1824 and 1827. Other journals from the expedition members were published later in the 1800s.

The full and complete version of the expedition's story was finally published in Spain by the Museo Naval and Ministerio de Defensa in nine volumes from 1987 to 1999. The second volume, Malaspina's journal, was translated into English and published between 2001 and 2005. The many drawings and paintings from the expedition were described in a book in 1982. The thousands of documents related to the expedition were organized and listed between 1989 and 1994.

Malaspina Expedition 2010

To honor Malaspina's important work, several Spanish groups launched a new scientific expedition around the world, also named after him. The Malaspina Expedition 2010 was a big research project. Its main goals were to study how global change affects the oceans and to explore the amazing variety of life (biodiversity) in them.

250 scientists sailed on two research ships, Hespérides and Sarmiento de Gamboa. They were on a nine-month journey from December 2010 to July 2011. Just like the original Malaspina Expedition, this modern trip combined new scientific research with training for young scientists. It also helped advance marine science and teach the public about science. The ships traveled a total of 42,000 nautical miles, stopping in many cities around the world before returning to Cádiz.

This project was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and led by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), with help from the Spanish Navy.

Images for kids

-

The Official Spanish Landing Plaque on Marcaciones point, Bauza Island, New Zealand

See also

In Spanish: Expedición Malaspina para niños

In Spanish: Expedición Malaspina para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |