Nootka Crisis facts for kids

The Nootka Crisis was a big disagreement between several powerful groups in the late 1700s. It involved the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation (the local Indigenous people), the country of Spain, the country of Great Britain, and the new country of the United States.

This dispute happened in the summer of 1789 at a Spanish outpost called Santa Cruz de Nuca, located in Nootka Sound. This area is now part of British Columbia, Canada. The Spanish commander there, Jose Esteban Martínez, seized some British trading ships. These ships were there for the maritime fur trade and to build a permanent trading post.

When news reached Britain, people were very upset. Both Britain and Spain prepared their navies, and it looked like war might break out. Both countries asked their allies for help. Spain's main ally, France, also got its navy ready. However, France soon announced it would not join the war. Without France's help, Spain knew it couldn't win against Britain and its allies. So, Spain decided to find a peaceful solution and made some agreements.

The crisis was solved peacefully through three agreements called the Nootka Conventions (from 1790 to 1795). These agreements allowed British traders to operate in areas near Spanish lands and to set up trading posts in places Spain didn't already occupy. Spain gave up many of its claims to land and trade in the Pacific Ocean. This ended Spain's control over Asian-Pacific trade, which had lasted for 200 years. This outcome was a big win for Britain's trading businesses and helped Britain expand its influence in the Pacific. For Spain and France, the crisis was seen as an international embarrassment. Spain later gave its historic claims in the Pacific Northwest to the United States in a treaty in 1819.

Contents

What Was It Called?

The events at Nootka Sound are sometimes called the Nootka Incident or the Nootka Sound Incident. The larger international disagreement is known by names like the Nootka Sound Crisis or the Great Spanish Armament.

Why Did It Happen?

The northwestern part of North America, known as the Pacific Northwest, was not well explored by European ships before the mid-1700s. But by the end of that century, several countries wanted control of the region. These included Great Britain, Spain, Russia, and the United States.

Spain's Claims to the Pacific Coast

For hundreds of years, Spain claimed the entire Pacific coast of North and South America. This claim was based on several things:

- In 1493, the Pope issued a special order that divided the Western Hemisphere between Spain and Portugal. This order, called Inter caetera, basically gave almost all of the New World to Spain.

- In 1513, the Spanish explorer Balboa crossed Panama and became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean from the Americas. He formally claimed all the lands touched by the Pacific Ocean for Spain.

Over time, new rules for claiming land developed in European law. These included "prior discovery" (being the first to find a place) and "effective occupation" (actually settling and controlling a place). Spain claimed to have discovered the northwest coast of North America through voyages by Cabrillo in 1542 and Vizcaino in 1602–03. However, these early voyages didn't go north of the 44th parallel. Also, Spain didn't have any "effective settlements" north of Mexico until much later.

When Russians started exploring Alaska and setting up fur trading posts in the mid-1700s, Spain reacted. They built a new naval base at San Blas, Mexico. From there, they sent ships to explore the far northwest. These trips aimed to check on the Russian threat and to strengthen Spain's "prior discovery" claims. Spain also started "effective settlements" in Alta California (present-day California). Between 1774 and 1789, Spanish expeditions went to northern Canada and Alaska to show Spain's long-held claims and navigation rights. By 1775, Spanish explorers had reached the mouth of the Columbia River and Sitka Sound.

Britain's Growing Interest

James Cook of the British Royal Navy explored the Pacific Northwest coast, including Nootka Sound, in 1778. His travel journals were published in 1784. They created a lot of excitement in Britain about the potential for fur trading in the region. Even before 1784, unofficial stories had already told British merchants about the possible profits. The first British trader to arrive after Cook was James Hanna in 1785. News of the large profit Hanna made selling furs in China encouraged many other British businesses.

Cook's visit to Nootka Sound, a group of inlets on the west coast of Vancouver Island, was later used by Britain to support its claim to the region. However, Cook didn't formally claim the land. Spain argued back, pointing to Juan Pérez, who had anchored in Nootka Sound in 1774.

By the late 1780s, Nootka Sound was the most important harbor on the northwestern coast. Russia, Britain, and Spain all wanted to control it permanently.

John Meares and British Trading

John Meares was a key figure in the early British fur trading efforts in the Pacific Northwest. After a difficult trip to Alaska in 1786–87, Meares returned to the region in 1788. He arrived at Nootka Sound with his ship, the Felice Adventurero, and another ship, the Iphigenia Nubiana. These ships were registered in Macau, a Portuguese colony in China. They used Portuguese flags to avoid the British East India Company's monopoly on trading in the Pacific. Ships not registered as British didn't need licenses from the East India Company.

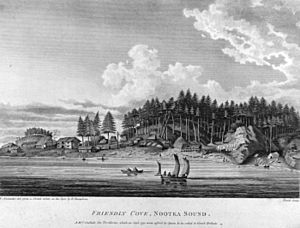

Meares later claimed that Maquinna, a chief of the Nuu-chah-nulth people, sold him some land at Friendly Cove in Nootka Sound. He said he paid with pistols and other trade goods, and that a building was put up on this land. These claims became a very important part of Britain's argument during the Nootka Crisis. Spain strongly disagreed with both claims, and the full truth is still debated.

However, it is certain that Meares's men and a group of Chinese workers built a small ship called the North West America. It was launched in September 1788. This was the first non-Indigenous ship built in the Pacific Northwest. The North West America also played a role in the Nootka Crisis, as it was one of the ships seized by Spain. At the end of the summer, Meares and his ships left the area.

Spain's Decision to Act

During the winter of 1788–89, Meares was in China. There, he and others formed a trading company. They planned for more ships to sail to the Pacific Northwest in 1789. These included the Princess Royal and the Argonaut. James Colnett was given overall command. Colnett's orders for 1789 were to set up a permanent fur trading post at Nootka Sound.

While the British traders were getting ready, the Spanish continued their efforts to secure the Pacific Northwest. Initially, Spain was mostly worried about Russian activity in Alaska. On a 1788 voyage to Alaska, Esteban José Martínez learned that the Russians planned to build a fort at Nootka Sound. This, along with the increasing number of British fur traders at Nootka Sound, led Spain to decide to claim full control of the northwest coast once and for all. They planned to colonize Nootka Sound. Spain hoped to establish and keep control over the entire coast as far north as the Russian posts in Prince William Sound.

The Viceroy of New Spain (the Spanish ruler in Mexico), Manuel Antonio Flórez, told Martínez to occupy Nootka Sound. He was to build a settlement and a fort, and make it clear that Spain was setting up a formal base.

In early 1789, the Spanish expedition under Martínez arrived at Nootka Sound. His force included the warship Princesa Real and the supply ship San Carlos. The expedition built British Columbia's first European settlement, Santa Cruz de Nuca, at Nootka Sound. This included houses, a hospital, and Fort San Miguel.

The Crisis Unfolds

The Nootka Incident

Martínez arrived at Nootka Sound on May 5, 1789. He found three ships already there. Two were American, the Columbia Rediviva and the Lady Washington, which had spent the winter at Nootka Sound. The third was a British ship, the Iphigenia. Martínez seized the Iphigenia and arrested its captain, William Douglas. After a few days, Martínez released Douglas and his ship, ordering him to leave and not come back. Douglas followed the order.

On June 8, the North West America, a British ship, arrived at Nootka Sound and was seized by Martínez. The ship was renamed Santa Gertrudis la Magna and used for exploring the area. Martínez later claimed that the captain had abandoned the ship. He also said he seized it as security for money owed by Meares's company for supplies he had given to the Iphigenia.

On June 24, in front of the British and Americans, Martínez formally claimed the entire northwest coast for Spain.

On July 2, the British ships Princess Royal and Argonaut arrived. Martínez ordered the Princess Royal's captain, Thomas Hudson, to leave the area. Later that day, the Argonaut arrived. Martínez seized the ship and arrested its captain, Colnett, along with his crew and the Chinese workers Colnett had brought. The Argonaut also carried a lot of equipment. Colnett said he planned to build a settlement at Nootka Sound. Martínez saw this as a violation of Spanish control and arrested Colnett after a heated argument.

Martínez later used the Chinese workers to build Fort San Miguel and improve the Spanish post. The Argonaut also carried materials to build a new ship. These materials were used to improve the seized North West America, which had been renamed Santa Gertrudis la Magna. This ship was later used for explorations, including by José María Narváez in the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

On July 12, Hudson returned to Nootka Sound with the Princess Royal. He didn't intend to enter, but his ship became stuck without wind. Martínez saw this as a challenge and seized the ship.

Conflict with the Nuu-chah-nulth

On July 13, Callicum, a leader of the Nuu-chah-nulth people and brother of Chief Maquinna, went to meet with Martínez. Callicum was on board the newly captured Princess Royal. Callicum's angry words and actions worried the Spanish, and Callicum was shot and killed. Stories differ on exactly how this happened. Some say Martínez fired a warning shot, and another Spanish sailor, thinking Martínez meant to kill, fired and killed Callicum. Others say Martínez aimed to hit Callicum but his gun misfired, and another sailor fired and killed him. The reason for Callicum's anger also differs in accounts. In any case, this event caused a serious break between the Spanish and the Nuu-chah-nulth. Maquinna, fearing for his life, fled to Clayoquot Sound with his people.

On July 14, the Argonaut sailed for San Blas, Mexico, with a Spanish crew and Colnett and his crew as prisoners. Two weeks later, the Princess Royal followed.

The American ships Columbia Rediviva and Lady Washington were also trading in the area that summer. Martínez left them alone, even though his orders were to stop all foreign ships from trading at Nootka Sound. The captured crew of the North West America was sent to the Columbia before the Americans sailed for China.

Despite the conflict and warnings, two other American ships arrived at Nootka Sound later in the season. The first, the Fair American, was captured by Martínez's forces. Its sister ship, the Eleanora, almost got caught but escaped.

By the end of October 1789, the Spanish completely left Nootka Sound. They returned to San Blas with the Princess Royal, the Argonaut, and the Fair American, along with their captured captains and crews. The captured North West America (renamed Santa Gertrudis la Magna) returned separately. The Fair American was released in early 1790. The Nootka Incident did not cause a crisis between the United States and Spain.

By late 1789, a new viceroy, Juan Vicente de Güemes, 2nd Count of Revillagigedo, had replaced Viceroy Flores. The new viceroy was determined to keep defending Spain's rights in the area. Martínez, who had been favored by Flores, became a scapegoat under the new leadership. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, a senior commander, replaced Martínez as the main Spanish official in charge of Nootka Sound. A new expedition was organized, and in early 1790, Spain reoccupied Nootka Sound under the command of Francisco de Eliza. This Spanish force was the largest ever sent to the northwest.

Countries React

News about the events at Nootka Sound reached London in January 1790. The main leaders involved were William Pitt the Younger, the British Prime Minister, and José Moñino y Redondo, conde de Floridablanca, Spain's chief minister.

Pitt claimed that the British had the right to trade in any Spanish territory they wanted, even if Spanish laws said otherwise. He knew this claim was hard to defend and might lead to war, but he felt pressured by public opinion in Britain.

In April 1790, John Meares arrived in England. He confirmed the rumors, claimed he had bought land and built a settlement at Nootka before Martínez, and generally stirred up anti-Spanish feelings. In May, the issue was discussed in the British Parliament, and the Royal Navy began preparing for war. Britain sent an ultimatum to Spain.

The Nootka Crisis was the first international crisis for the new United States of America under its first president, George Washington. Important thinkers like Thomas Paine believed the crisis could drag the US into a European war.

Meares published his book Voyages in 1790, which became very popular, especially with the Nootka Crisis developing. Meares not only described his trips but also presented a big idea for a new economic network in the Pacific. This network would connect places like the Pacific Northwest, China, Japan, Hawaii, and England through trade. This idea was similar to Spain's old trade routes, which had linked Asia and the Philippines with North America and Spain for centuries. Meares strongly argued for reducing the power of the East India Company and the South Sea Company, which controlled all British trade in the Pacific. His vision eventually came true, but not until after the long Napoleonic Wars.

Both Britain and Spain sent powerful fleets of warships towards each other to show their strength. There was a chance of open warfare if the fleets had met, but they did not.

France's role was very important. France and Spain were allies under the Family Compact, an agreement between their ruling families. The combined French and Spanish navies would have been a serious threat to Britain's Royal Navy. The French Revolution had started in July 1789, but it hadn't become too serious by the summer of 1790. King Louis XVI was still the ruler, and the French military was mostly intact. In response to the Nootka Crisis, France mobilized its navy. But by the end of August, the French government decided it could not get involved. The National Assembly, which was gaining power, declared that France would not go to war. Spain's position was weakened, and negotiations to avoid war began.

The Dutch Republic provided naval support to the British during the Nootka Crisis. This was because the Dutch had shifted their alliance from France to Britain. This was the first test of the Triple Alliance between Britain, Prussia, and the Dutch Republic.

Without France's help, Spain decided to negotiate to avoid war. The first Nootka Convention was signed on October 28, 1790.

The Nootka Conventions

The first Nootka Convention, also called the Nootka Sound Convention, generally resolved the crisis. The agreement stated that the northwest coast would be open to traders from both Britain and Spain. It also said that the captured British ships would be returned and that Spain would pay for damages. It also stated that the land owned by the British at Nootka Sound would be given back. This part was hard to carry out. Spain claimed that the only land owned by the British was a small piece where Meares had built the North West America. Britain argued that Meares had bought all of Nootka Sound from Maquinna, as well as some land to the south. Until these details were worked out, which took several years, Spain kept control of Nootka Sound and continued to have a fort at Friendly Cove.

The relationship between the Nuu-chah-nulth and Spain also changed. The Nuu-chah-nulth became very suspicious and hostile towards Spain after the killing of Callicum in 1789. But the Spanish worked hard to improve the relationship. By the time the Nootka Conventions were being carried out, the Nuu-chah-nulth were mostly allied with the Spanish. This happened largely because of the efforts of Alessandro Malaspina and his officers during their month-long stay at Nootka Sound in 1791. Malaspina was able to regain Maquinna's trust and his promise that the Spanish had the rightful claim to land ownership at Nootka Sound. Before this dispute, the Spanish had enjoyed special access to the area and had good relations with the Nuu-chah-nulth people, based on their claims to the entire Northwest Coast.

Negotiations between Britain and Spain about the details of the Nootka Convention were supposed to happen at Nootka Sound in the summer of 1792. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra came for Spain. The British negotiator was George Vancouver, who arrived on August 28, 1792. Vancouver believed his job was to get back the land and property seized from the British fur traders in 1789. He also thought he was to set up a formal British presence there to support the fur trade. Plans to establish a British colony on the North West Coast had been discussed in the 1780s.

Vancouver also believed that once he got Nootka Sound back, he was to prepare for founding a British colony there. He was also told to map the region and try to find a sea route from it to the North Atlantic, the long-sought Northwest Passage. However, British policy towards Spain became more friendly after he left England in April 1791, due to challenges from the French Revolution. This change was not told to him, which made his negotiations with the Spanish commander difficult.

Even though Vancouver and Bodega y Quadra were friendly, their talks didn't go smoothly. Spain wanted to set the Spanish-British border at the Strait of Juan de Fuca. But Vancouver insisted on British rights to the Columbia River. Vancouver also didn't like the new Spanish post at Neah Bay. Bodega y Quadra insisted that Spain keep Nootka Sound, which Vancouver could not accept. In the end, they both agreed to let their governments decide.

By 1793, Britain and Spain had become allies in a war against France. The issues of the Nootka Crisis became less important. An agreement was signed on January 11, 1794. Both nations agreed to leave Nootka Sound. There was a ceremony to transfer the post at Friendly Cove to the British.

The official transfer happened on March 28, 1795. José Manuel de Álava represented Spain, and Lieutenant Thomas Pearce represented Britain. The British flag was ceremonially raised and lowered. Afterwards, Pearce gave the flag to Maquinna and asked him to raise it whenever a ship appeared.

Under the Nootka Convention, Britain and Spain agreed not to build any permanent bases at Nootka Sound. However, ships from either nation could visit. The two nations also agreed to stop any other country from claiming control there.

What Happened Next?

The Nootka Conventions changed the idea that a country could claim full control over land without actually settling it. It was no longer enough to claim territory just by a Pope's order or by being the "first to discover" it. Claims had to be supported by some kind of actual occupation. This shift from symbolic claims to physical occupation marked the end of an era. Nations now had to be physically present to claim a territory.

For Spain, the outcome of the crisis was a humiliation and a big blow to their government and empire. They felt betrayed by France and had to look for support elsewhere in Europe. It also showed a larger embarrassment for France, just as it had done two decades before in the Falklands Crisis. Again, Spain had looked to its French ally for help against British expansion, and again France had failed to act strongly.

For the British, the outcome was a triumph. It was understood that Spain had no rights by occupation north of San Francisco. That region was then opened up to British trade, and after the crisis, Britain became the main power in the Pacific. The victory also increased the popularity of Prime Minister Pitt. Britain felt it had gotten revenge on Spain for its involvement in the American war of independence. Also, the successful mobilization by the Royal Navy showed that it had recovered well from that war. However, the British did not win every point they wanted. British merchants were still restricted from trading directly with Spanish America, and no northern boundary for Spanish America was set.

Spanish rights in the Pacific Northwest were later acquired by the United States through the Adams–Onís Treaty, signed in 1819. The United States argued that it gained full control from Spain. This became a key part of the American position during the Oregon boundary dispute. To counter the US claim of full control, the British referred to the Nootka Conventions. This dispute was not resolved until the signing of the Oregon Treaty in 1846. This treaty divided the disputed territory and set what later became the current border between Canada and the United States.