Californios facts for kids

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 300,000–500,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish (American Spanish, Mexican Spanish), English (California English, Chicano English), Caló, Indigenous languages of California, Indigenous languages of Mexico | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Chicanos and Hispanos of the United States: Tejanos, Neomexicanos Other Hispanic and Latino peoples: Chicanos, Mexican Americans, Mexicans, Spaniards, Indigenous Mexican American, Spanish Americans, Louisiana Criollos, Louisiana Isleños Other California Hispanics: Basque Californians |

A Californio (plural Californios) is a term for a Hispanic Californian. It especially refers to people whose families came from Spanish and Mexican settlers. The Spanish-speaking community has lived in California since 1683. They have roots from Spain, Mexico, mixed backgrounds (Mestizo), and Native Californian groups. Californios are part of the larger Chicano/Mexican-American/Hispano community in the American Southwest and West Coast. This community has been in the region since the 1500s.

The word Californio originally described Spanish-speaking people living in Las Californias. This was during the times of Spanish California and Mexican California, from 1683 to 1848. The first Californios were children of early Spanish military groups who explored northern California. They built military forts called presidios. These forts helped start the California mission system.

Later, Californio culture focused on the Vaquero (cowboy) tradition. This was practiced by wealthy landowners who received large land grants. They created the Rancho system. From the 1820s to 1840s, more American and European settlers moved to Mexican California. Many married Californio women and became Mexican citizens. They learned Spanish and often became Catholic. These newcomers are also often considered Californios because they adopted the language and culture.

In 2017, about 11.9 million Chicanos/Mexican Americans/Hispanos lived in California. This was 30% of the state's population. They are the largest group among the 15.2 million California Hispanics, who make up 40% of California's population. Studies in 2004 estimated that between 300,000 and 500,000 people today have ancestors from the Spanish and Mexican times in California.

Contents

What Does "Californio" Mean?

The word "Californio" can mean different things to different people.

- The Real Academia Española says a Californio is someone born in California.

- The Merriam-Webster dictionary says it's a native or resident of California, or a specific ethnic group: Spanish settlers and their descendants.

Some historians, like Douglas Monroy, say "Californio" only refers to people who lived in Alta California and their descendants. Others, like Hunt Janin, include any settler who moved to Alta California and their descendants. They also include non-Hispanic immigrants who married into Hispanic families and became part of Californio culture during the Mexican era.

Some sources, like Calisphere, limit the term "Californio" to the wealthy Californian families who got land during the Spanish and Mexican periods. However, most agree that "Californio" at least includes Hispanic people whose families originated in Alta California.

Californio History: Early Days

Spanish Explorers and First Settlements

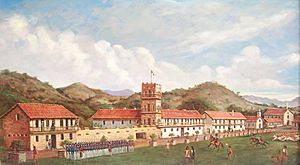

In 1769, Gaspar de Portolá led an expedition with fewer than 200 men. They founded the Presidio of San Diego, which was a military fort. On July 16, Franciscan friars, including Junípero Serra, started the first mission in upper Las Californias, called Mission San Diego de Alcalá. More colonists began to arrive in 1774.

Monterey, California was founded in 1770 by Father Junípero Serra and Gaspar de Portolà. Monterey became the capital of California from 1777 to 1849. The nearby Carmel Mission was moved to Carmel to keep the mission and its Mission Indians separate from the soldiers at the Monterey Presidio. Monterey was the main port for all goods entering California. Ships had to stop there to pay taxes before trading elsewhere.

Overland Expeditions and New Towns

Late in 1775, Colonel Juan Bautista de Anza led an overland journey. He brought colonists from Sonora in New Spain (Mexico) to California. Anza led 240 friars, soldiers, and families. They brought many horses and cattle, which helped start the cattle and horse industry in California. In 1776, about 200 soldiers and colonists moved to Yerba Buena (now San Francisco). They began building a mission and a presidio there.

Anza chose the locations for the Presidio of San Francisco and Mission San Francisco de Asís in San Francisco. On his way back, he also picked sites for Mission Santa Clara de Asís and the town of San Jose. Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) was founded on June 29, 1776.

On November 29, 1777, El Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe (San Jose) was founded. It was the first town in Alta California not linked to a mission or military fort. The first settlers of San Jose were part of the group that had settled Yerba Buena. Mission Santa Clara, founded in 1777, was the closest mission to San Jose.

The Los Angeles Pobladores were 44 original settlers from Sonora, Mexico, who founded Los Angeles in 1781. These families were mostly farmers. They were the last to use the Anza trail before it was closed for 40 years. Most of these settlers were not "Spanish" (from Spain). They had mixed backgrounds, including mestizo (Spanish and Native American), indio (Native American), and negro (African).

The settlers and soldiers who founded towns like San José, Yerba Buena, Monterey, San Diego, and Los Angeles were mainly of mixed heritage from Mexico. It was hard to convince people to move to California because it was so isolated. Most settlers came from northwestern Mexico.

In Californio society, a person's background was important. The term gente de razón meant "people of reason." It referred to people who were culturally Hispanic and Christian. This helped tell the difference between Mexican Native American settlers and Californian Native Americans who had not converted. California's Governor Pío Pico was criticized because his family had mixed backgrounds.

Californio History: Mexican Rule and U.S. Conquest

Changes Under Mexican Rule

In the 1830s, the new Mexican government faced many challenges. One big issue was how much land the Catholic Church controlled. In California, Franciscan friars controlled over 90% of all settled land. This land was supposedly held for the mission Indians.

In 1834, new laws called secularization laws were passed. These laws took control of lands away from the missions. The missions had used thousands of Native Americans to herd animals, grow crops, and make cloth. The mission lands and animals were then given to settlers around each mission. Since most settlers had little money, the land was often given for free or very cheaply to friends and families of government officials.

For example, Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, a Californio, became very wealthy. He oversaw the secularization of Mission San Francisco Solano and received huge land grants. He founded towns like Sonoma and Petaluma, California. Vallejo owned vast amounts of land and many animals. He was known for his hospitality and entertained many travelers.

When the missions were secularized, Native Americans no longer had to live under the friars' control. Many returned to their tribes. Others found work on the large ranches that took over the mission lands. Many Native Americans who learned to ride horses became vaqueros (cowboys). These rancho owners and their workers made up most of the Californios who fought in the short Mexican-American War in California. Some Californios and California Native Americans even fought with the U.S. settlers.

U.S. Takes Control of California

Before the Mexican–American War (1846–1848), Californios forced the Mexican governor, Manuel Micheltorena, to leave California. Pío Pico, a Californio, was the governor during the conflict.

The Pacific Squadron, the U.S. Navy force in the Pacific, helped capture Alta California. They had orders to seize ports in Mexican California if war broke out. The only other U.S. military force was a small group led by Lieutenant Colonel John C. Frémont.

Rumors spread that the Californio government planned to arrest new American residents. So, on June 14, 1846, thirty-three settlers in Sonoma Valley captured the small Californio military post without a fight. They raised a homemade flag with a bear and a star, which became known as the "Bear Flag". This event was called the "Bear Flag Revolt".

On July 7, 1846, U.S. Marines and sailors captured Monterey, California, the capital of Alta California. Two days later, they captured Yerba Buena (San Francisco). The British navy ships in the area watched but did not get involved.

Soon after, the short-lived Bear Flag Republic became a U.S. military occupation. The U.S. flag replaced the Bear Flag. Commodore Robert F. Stockton became the senior U.S. military commander. He asked Frémont's group to form the California Battalion.

The California Battalion helped capture San Diego and Los Angeles. On August 13, Stockton and Frémont's combined forces entered Los Angeles without a fight. However, Major Archibald Gillespie put Los Angeles under strict military rule, which angered many Californios. On September 23, 1846, about 200 Californios, led by General José María Flores, revolted. Gillespie and his men had to retreat.

It took about four months for Los Angeles to be retaken. This happened without a fight on January 10, 1847. After losing the Battle of La Mesa, the Californio government signed the Treaty of Cahuenga. This treaty ended the war in California on January 13, 1847. The main Californio military force, the lancers, was disbanded. Some Californios fought on both sides during the conflict.

Key Californio Battles

Most towns in California surrendered peacefully. The few fights that happened involved small groups of Californios and U.S. soldiers or militia.

- Battle of Dominguez Rancho, October 9, 1846: Californio forces led by José Antonio Carrillo defeated U.S. Marines and sailors near Los Angeles.

- Battle of San Pasqual, December 6, 1846: U.S. General Stephen W. Kearny's forces, tired from a long journey, fought about 150 Californio lancers led by Andrés Pico. Kearny's side suffered more losses.

- Battle of Río San Gabriel, January 8, 1847: U.S. forces led by Kearny and Stockton defeated the Californio lancers near Los Angeles.

- Battle of La Mesa, January 9, 1847: U.S. forces defeated the Californios in the final battle in California, near Montebello.

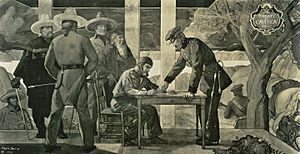

On January 13, 1847, at a deserted rancho, John C. Frémont and Andrés Pico signed the Treaty of Cahuenga. This agreement ended the fighting in California.

Californios After U.S. Annexation

In 1848, the U.S. Congress created a board to check the validity of Mexican land grants in California. The California Land Act of 1851 said that landowners had to prove their ownership within two years. If not, the land would become public property. Rancho owners argued that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo protected their property rights.

Many rancho owners, with their large lands and animals, continued to live well under U.S. rule. Andrés Pico, a former Californio military leader, became a U.S. citizen and a California State Assemblyman and Senator. His brother, Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor, also became a U.S. citizen and a successful ranch owner. However, many others were not as lucky. Droughts in the early 1860s killed their animals. They lost their land because they couldn't repay loans they had taken out.

Californios did not disappear. Many people today still identify strongly as Californios. Thousands have detailed family histories showing their Californio roots.

California's growing farming economy allowed many Californios to continue living in towns alongside Native peoples and Mexicans. These settlements grew into modern California cities like Santa Ana, San Diego, and San Jose.

From the 1850s to the 1960s, Hispanic people in California lived somewhat separately. They had Spanish-language newspapers, entertainment, schools, and clubs. Their cultural practices were often linked to local churches. Over time, official records started grouping all Californios, Mexicans, and Native Americans with Spanish last names together. Some Californios even married Mexican Americans whose families came to California later.

It is estimated that in 2004, there were between 300,000 and 500,000 descendants of Californios.

Californios and the Gold Rush

In 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in California. This happened just nine days before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, which gave California to the United States.

Many Newcomers Change California

From late 1849 to late 1852, California's population grew from 107,000 to 264,000 because of the California Gold Rush. In early 1849, about 6,000 Mexicans, including Californios, were already looking for gold. Even though the land had recently been Mexican, Californios quickly became a minority. They were seen as foreigners.

When the Gold Rush truly began in 1849, mining camps were often separated by nationality. This showed that "Americans" were now the main group in Northern California. Because Californios became a minority so quickly, their land claims, protected by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, were often ignored. Miners would take over their land. Any protests by Californios were often stopped by American groups. Even if Californios won their land back in court, lawyer fees often cost them large parts of their property.

Difficult Working Conditions

Many Latino miners were skilled at "dry-digging" from their experience in Mexico. At first, their success earned them respect. But soon, Euro-American miners became jealous. They used threats and violence to force Mexican workers off their good plots. They also tried to create laws to stop Latinos from mining. In 1851, violence and a high tax on foreign miners forced thousands of foreign workers out of their jobs.

Accounts from people like Antonio F. Coronel show that Americans often used violence to remove Californios and other Latinos. Coronel himself found a rich gold vein, but armed Euro-Americans forced him off his claim. These stories show the harsh conditions Californios faced during the Gold Rush. They were forced out of their lands despite the treaty that said they could stay.

The Foreign Miners' Tax

White miners wanted something done about the "Sonoran" (Mexican) miners. In response, California introduced the Foreign Miners' Tax Law in 1850. This tax was very high, possibly $20 to $30 per month. This made it impossible for most Latinos to make a profit from mining. By 1851, when the tax was removed, about two-thirds of the Latinos and Californios in mining areas had been driven out. In 1852, a more reasonable $3 per month tax was put in place.

Californio Society and Customs

Government and Power

In the Spanish period, Alta California was ruled by a governor appointed by Spain. After 1821, when Mexico became independent, Mexican presidents appointed the governors. The government's costs were mostly paid by taxes on imported goods collected at the port of Monterey.

The Franciscan friars also had much power as heads of 21 missions. They often disagreed with the governors. No Franciscan friars were Californios. Their power quickly faded after Mexico took control of the missions in the 1830s.

The Mexican government was unstable, and Alta California was far away. This led to disagreements between Californios and the central government. Governors had little support from Mexico City. Californios started to gain power in the Alta California government. This led to rivalries between northern and southern regions. Californio leaders, like Juan Bautista Alvarado in 1836, tried to break away from Mexico several times.

Foreigners and Mixed Heritage

More immigrants, mostly English and French, came to California. They often became part of Californio society. They became Mexican citizens and gained land, sometimes by marrying Californio women. They also became active in local politics.

Californios were often of mixed backgrounds. Most were Mestizo (Spanish and Native American) or had African and Native American roots. Few Californios were of "pure" Spanish ancestry. Spanish priests, government officials, and military officers were more likely to be from Europe.

Many soldiers who came to California retired there. Because there were more men than women among the Spanish, some men married Native Californian women who had converted to Christianity at the missions.

Family Life and Education

Californio families were usually led by the father. Sons were expected to obey their fathers for life. Women had full rights to own and control property unless they were married or their father was alive. Wealthy families paid for their children to be educated by priests or private teachers. Few early immigrants could read or write.

Women in Californio Society

Social life was very important in Californio society, and women played a big part. They helped their husbands with social and business interactions to gain power. Men looked for women with good social skills.

In movies and TV, Californio women are often shown as beautiful and fun-loving. They are also shown as being very protected.

Women were important in the development of Alta California. As more non-Spanish speaking men moved to California, some married women from established Californio families. This was a way for them to join the elite. Marriages between Californios and foreigners were common under Mexican rule and increased after the U.S. took over. These marriages mixed American and Californio cultures. However, as Americans grew in number, Californios lost power in California.

Land and Ranchos

Before Mexico's independence in 1821, only 20 "Spanish" land grants were given in Alta California. Many went to friends and family of the governors. In 1824, Mexico made rules for asking for land grants. When the missions were secularized in 1834–1836, most mission property and animals were supposed to go to the Mission Indians. However, most rancho grants went to retired soldiers.

Many foreigners also received rancho grants. Some became Californios by marriage. Rancho ownership was possible for these men because, under Spanish/Mexican law, married women could own property independently.

In practice, most mission property and animals became about 455 large Ranchos of California. Californio rancho owners claimed about 8.6 million acres. This land was mostly former mission land near the coast. The boundaries of these ranchos were often unclear. This caused problems when the U.S. took control and reviewed the land grants.

Rancho Culture

After the California Missions established farming and raising animals, rancho owners took over the mission lands and animals starting in 1834. The Mission Indians were left to find their own way. Rancho owners tried to live a grand lifestyle, like wealthy nobles in Spain. They expected others to support this way of life. Almost all men rode horses everywhere, making them excellent riders. They enjoyed many fiestas, fandangos (dances), rodeos, and roundups. Weddings, christenings, and funerals were all big celebrations.

Taxes and Horses

The government relied on taxes on imported goods for its income. There was almost no property tax. Under Spanish/Mexican rule, landowners had to pay a tithe (one-tenth of their income) to the Catholic Church. This money paid for priests and mission expenses. This mandatory tithe ended when the missions were secularized.

Horses were very common. Riders would often use one horse until it was tired, then switch to another. Horse ownership was almost like community property. Horses were so common that they were sometimes killed to save grass for cattle. California Native Americans later started eating horse meat, which helped control their numbers. Horses were also used to separate wheat or barley from the chaff by having them walk around in a circular corral.

Native American Workers and Trade

For the few rancho owners, this was a "Golden Age." But for others, it was different. Much of the farming started by the Missions declined as the Native American population decreased. Fewer Native Americans meant less food was needed. After the friars and soldiers left in 1834, many Native Americans left the missions. Some returned to their tribes, while others found work on the new ranches. The ranches often hired former mission Native Americans. These workers received room, board, and clothing, but no pay. They did most of the work herding cattle and farming.

From 1769 to 1824, California saw only about 2.5 ships per year. These ships brought new settlers and supplies. Spain discouraged trade with non-Spanish ships. The missions and towns were supported by the Spanish government. After 1824, Mexico allowed trade with non-Mexican ships. The number of ships visiting California jumped to 25 per year.

Rancho society had few resources except large herds of Longhorn cattle. These cattle thrived in California. The ranchos became the biggest producers of cowhides (called California Greenbacks) and tallow (animal fat) in North America. Cowhides were dried, and tallow was put into large bags. With these goods to trade, Californios could get things they needed, like nails, needles, cloth, and fancy clothes. They traded with merchant ships from Boston, Massachusetts, Britain, and other places. The journey from Boston could take over 200 days one way. Trading ships would stop at ports like San Diego, San Juan Capistrano, and Monterey. They had to pay a tax on imports at Monterey. These taxes paid for the Alta California government.

Notable Californios

|

|||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other Hispanos of the United States: Tejanos, Neomexicanos Other Hispanic and Latino peoples: Chicanos, Mexican Americans, Mexicans, Spaniards, Indigenous Mexican American, Spanish Americans, Louisiana Criollos (Isleños) |

|||||||||||

In 1845, the Californio population was estimated at 10,000.

- Juan Bautista Alvarado, governor

- Arcadia Bandini, businesswoman and co-founder of Santa Monica, California

- Juan Bandini

- José Antonio Carrillo

- María Ygnacia López de Carrillo, founder of Santa Rosa, California

- José Castro, general of the Mexican army in Alta California

- Antonio F. Coronel

- Angustias de la Guerra Ord

- William Edward Petty Hartnell, also known as Don Guillermo Arnel

- Eulalia Pérez de Guillén Mariné

- Romualdo Pacheco, 12th Governor of California

- Luís María Peralta, recipient of the Rancho San Antonio (Peralta) land grant

- Andrés Pico

- Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of Alta California

- Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, founder of Sonoma, California

- Francisca Benicia Carrillo Vallejo, namesake of Benicia, California

- Tiburcio Vasquez, bandit

- Bernardo Yorba, major land grant recipient, namesake of Yorba Linda, California

Californios in Books and Stories

- Richard Henry Dana, Jr. wrote about Californio culture in his book Two Years Before the Mast (1840). He visited California as a sailor in 1834.

- Joseph John Chapman, an early settler in Los Angeles, described Southern California as a paradise. He wrote about the Spanish-speaking colonists, "Californios," who lived in towns, missions, and ranches.

- Alejandro Murguía writes about growing up in the 20th century and his family's Californio history in The medicine of memory : a Mexica clan in California.

- The novel Ramona (1884) by Helen Hunt Jackson shows Californio culture.

- The fictional character of Zorro is the most famous Californio. He appears in novels, short stories, movies, and a 1950s TV series. Sometimes, the historical facts are changed in these stories.

See also

In Spanish: Californios (grupo étnico) para niños

In Spanish: Californios (grupo étnico) para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |