Spanish language in the United States facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United States Spanish |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Spanish Español estadounidense |

||||

| Native to | United States | |||

| Native speakers | 42 million (2022) | |||

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

|||

| Early forms: |

Old Latin

|

|||

| Writing system | Latin (Spanish alphabet) | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Regulated by | North American Academy of the Spanish Language | |||

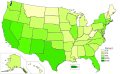

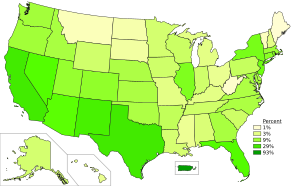

Percentage of the U.S. population aged 5 and over who speak the Spanish language at home in 2019, by states.

|

||||

|

||||

Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States. More than 42 million people aged five or older speak Spanish at home. It is also the most learned language after English. About 8 million students are learning Spanish. Experts believe up to 57 million people speak Spanish. This includes native speakers, people who learned it from family (called heritage language speakers), and those who learned it as a second language. There is even a special group called the Academy of the Spanish Language in the United States.

More people speak Spanish in the United States than French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Hawaiian, Chinese, Indian languages, and Native American languages all put together. In 2022, the US Census Bureau found that 42 million people aged five or older spoke Spanish at home. This is more than double the number from 1990.

Spanish has been spoken in what is now the United States since the 1400s. This started when Spanish explorers arrived in North America. They settled in areas like Florida, Texas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. They also settled in Puerto Rico. Spanish explorers visited 42 of the future US states. They left behind a lot of Hispanic culture and history. Parts of the Louisiana Territory were also under Spanish rule from 1763 to 1800. This happened after the French and Indian War. This spread Spanish influence even more across the United States.

Later, these areas became part of the United States in the 1800s. Spanish was then made stronger when the U.S. got Puerto Rico in 1898. Many people have also moved to the U.S. from Mexico, Cuba, Venezuela, El Salvador, and other parts of Latin America. This has made Spanish even more important in the country. Today, Hispanic people are one of the fastest growing groups in the U.S. This has increased the use of Spanish. However, fewer Hispanic people are speaking Spanish at home. The number went from 78% in 2006 to 73% in 2015. This trend is growing as more Hispanic people switch to speaking English.

Contents

- History of Spanish in the U.S.

- How Many Spanish Speakers Over Time

- Spanish Today in the U.S.

- Place Names from Spanish

- Learning Spanish in the U.S.

- Spanish Radio and Media

- How Spanish Varies in the U.S.

- English Words from Spanish

- How Spanish Sounds in the U.S.

- Spanish Words and Grammar in the U.S.

- The Future of Spanish in the U.S.

- Spanish Literature in the U.S.

- Images for kids

- See also

History of Spanish in the U.S.

Early Spanish Settlements

Spanish people first arrived in what is now the United States in 1493. They came to Puerto Rico. Juan Ponce de León explored Florida in 1513. In 1565, the Spanish founded St. Augustine, Florida. This is the oldest European settlement in the U.S. that has been lived in continuously. Juan Ponce de León also founded San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1508. Over time, more Spanish speakers came to the U.S. This happened because of land being taken over by the U.S. from the Spanish Empire. It also happened because of wars with Mexico and land purchases.

Spanish Louisiana

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, Spain controlled a large part of what is now the U.S. This included the French colony of Louisiana from 1769 to 1800. To make Louisiana stronger, Spanish Governor Bernardo de Gálvez asked people from the Canary Islands to move there. Between 1778 and 1779, about 1600 Isleños arrived in New Orleans. Another 300 came in 1783. By 1780, four Isleño communities were set up. When Louisiana was sold to the United States, its Spanish, Creole, and Cajun people became U.S. citizens. They continued to speak Spanish or French. In 1813, George Ticknor started a program to study Spanish at Harvard University.

Spain also built towns along the Sabine River. This was to protect the border with French Louisiana. The towns of Nacogdoches, Texas and Los Adaes were part of this plan. People there spoke a special kind of Spanish from rural Mexico. This way of speaking is now almost gone.

Texas and the Mexican-American War

In 1821, Mexico became independent from Spain. Texas was then part of Mexico. Many Americans soon moved to Texas. In 1836, these Texans fought for independence from Mexico. They did not like that Mexico had ended slavery. They created the Republic of Texas. In 1846, Texas joined the United States. By 1850, only a small number of Texans (7.5%) were of Mexican background and spoke Spanish. English speakers greatly outnumbered them.

After Mexico's independence from Spain, other areas also became part of Mexico. These included California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, western Colorado, and southwestern Wyoming. Most of New Mexico, western Texas, southern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, and the Oklahoma panhandle were also Mexican territory. Because these areas were far away and had a unique history, the Spanish spoken there became different. This is known as New Mexican Spanish.

Mexico lost almost half of its northern land to the United States. This happened during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). The land included parts of Texas, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, California, Nevada, and Utah. Thousands of Spanish-speaking Mexicans in these areas became U.S. citizens. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) ended the war. It did not directly talk about language. Spanish was still used in schools and government at first. However, English-speaking American settlers moved in. They made their language, culture, and laws the main ones. Spanish was used less in public life.

California is a good example. In 1849, California had its first meeting to write a constitution. Eight Californio people who spoke Spanish were there. The constitution was written in both English and Spanish. It said that all laws had to be published in both languages. One of the first things the California Legislature did in 1850 was to hire a State Translator. This person would translate all laws and documents into Spanish.

This helpful approach did not last long. By February 1850, California started using English law. In 1855, California said that English would be the only language used in its schools. These rules helped English speakers become more powerful in society and politics.

By 1872, California had another meeting for its constitution. No Spanish-speaking people were there. The English speakers felt that the remaining Spanish speakers should just learn English. They voted to change the rule. From then on, all official things would only be in English.

Even though Spanish was used less in public, many areas near the border still had Spanish-speaking communities. This included Southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, and South Texas. This lasted until at least the early 1900s.

Spanish-American War (1898)

In 1898, the United States gained control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. This happened after the Spanish–American War. In 1902, Cuba became independent. Puerto Rico, however, remained a U.S. territory. The American government wanted services to be in both Spanish and English. They also tried to teach in English in Puerto Rico. But this effort did not work well.

In 1948, Puerto Rico gained more control over its own government. Even U.S. officials who came to Puerto Rico had to learn Spanish. Only about 20% of Puerto Rico's people understand English. The island's government had a rule for both languages. But in 1991, they changed it to Spanish only. This rule was changed back in 1993. This happened when a party that wanted Puerto Rico to become a U.S. state won the election.

Hispanics Become the Largest Minority Group

Many Spanish speakers have moved to the United States recently. This has greatly increased the total number of Spanish speakers in the country. They make up large groups in many areas. This is especially true in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. These are the states that border Mexico. They are also a large group in South Florida.

Mexicans first came to the U.S. as refugees during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917). Many more came later for economic reasons. Most Mexicans live in the Southwest, in areas that used to be part of Mexico. From 1942 to 1962, the Bracero program brought many Mexican workers to the U.S.

Puerto Ricans are the second largest Hispanic group, with over 5 million people. They are the least likely of major Hispanic groups to be good at Spanish. However, millions of Puerto Rican Americans living in the U.S. are fluent in Spanish. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens from birth. Many have moved to New York City, Orlando, Philadelphia, and other cities in the Eastern United States. This has increased the number of Spanish speakers there. In some areas, they are the majority of the Spanish-speaking population, especially in Central Florida. In Hawaii, where Puerto Rican and Mexican workers settled long ago, seven percent of the people are Hispanic or speak Spanish.

The Cuban Revolution in 1959 caused many Cuban exiles to leave Cuba. Many of them came to the United States. In 1963, the Ford Foundation started the first bilingual education program in the U.S. This was for the children of Cuban exiles in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 led to more people moving from Latin American countries. In 1968, Congress passed the Bilingual Education Act. Most of these one million Cuban Americans settled in southern and central Florida. Others live in the Northeastern United States. Most of them speak Spanish fluently. In Miami today, Spanish is the main language, mostly because of Cuban immigration. Similarly, the Nicaraguan Revolution and Contra War in the late 1980s caused many Nicaraguans to flee to the U.S. Most of these Nicaraguans moved to Florida and California.

Many Salvadorans left their country because of money problems and civil war. The biggest wave of people leaving happened during the Salvadoran Civil War in the 1980s. About 20 to 30 percent of El Salvador's people moved away. About half of them, up to 500,000, came to the United States. The U.S. already had over 10,000 Salvadorans. This made Salvadoran Americans the fourth-largest Hispanic group in the U.S.

As civil wars happened in Central American countries in the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans fled. Between 1980 and 1990, the number of Salvadoran immigrants in the U.S. grew almost five times. It went from 94,000 to 465,000. More Salvadoran immigrants kept coming in the 1990s and 2000s. This was because families reunited and new people fled natural disasters in El Salvador. By 2008, about 1.1 million Salvadoran immigrants lived in the United States.

Before the 1900s, there were no clear records of Venezuelans moving to the U.S. Between the 1700s and early 1800s, many Europeans went to Venezuela. Later, they moved to the U.S. with their children and grandchildren. These children grew up in Venezuela speaking Spanish. From 1910 to 1930, it is thought that over 4,000 South Americans came to the U.S. each year. Many Venezuelans settled in the U.S. to get a better education. They often stayed after graduating. Their relatives often joined them. Since the early 1980s, Venezuelans have also moved for better pay. Economic changes in Venezuela also led many Venezuelan professionals to move to the U.S. In the 2000s, some Venezuelans who disagreed with their government moved to South Florida. They often settled in the suburbs of Doral and Weston. Other states with Venezuelan American populations include New York, California, Texas, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Maryland.

People from Spain also moved to the U.S. This was because of the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). There was also political trouble under Francisco Franco's rule until 1975. Most Spaniards settled in Florida, Texas, California, New Jersey, New York City, Chicago, and Puerto Rico.

In 2003, the United States Census Bureau announced that Hispanic people were the largest minority group in the U.S. This made people in Spain wonder about the future of Spanish in the U.S. That year, the Instituto Cervantes opened a branch in New York. This group was created by the Spanish government to promote the Spanish language worldwide.

How Many Spanish Speakers Over Time

| Year | Number of native Spanish-speakers | Percent of US population |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 11 million | 5% |

| 1990 | 17.3 million | 7% |

| 2000 | 28.1 million | 10% |

| 2010 | 37 million | 13% |

| 2015 | 41 million | 13% |

| 2022 | 42 million | 13.3% |

| Sources: | ||

In 2010, the census showed that 36,995,602 people aged five or older spoke Spanish at home. This was 12.8% of the total U.S. population.

Spanish Today in the U.S.

The United States does not have an "official language" by law. However, English is the main language for business, school, government, and media. Almost all government groups and large companies use English for their work. Some states, like Arizona, California, Florida, New Mexico, and Texas, provide official papers in both Spanish and English. English is the language most Americans speak at home. This includes more and more Hispanic people. Between 2000 and 2015, the number of Hispanic people who spoke Spanish at home went down from 78% to 73%. The only big exception is Puerto Rico. There, Spanish is the official and most used language.

Throughout the history of the Southwest U.S., language has been a sensitive topic. People have argued about language rights and having government representation in both languages. Spanish is now the most widely taught second language in the United States.

Place Names from Spanish

Many places in the U.S. have Spanish names. This is because much of the U.S. was once controlled by Spain and then Mexico. These names include several states and big cities. Some names keep older Spanish spellings, like San Ysidro. In modern Spanish, this would be Isidro. Later, many other names were created by non-Spanish speakers. Sometimes, these names did not follow Spanish grammar rules. An example is Sierra Vista.

Learning Spanish in the U.S.

In 1917, the American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese was started. Studying Spanish literature in schools became more popular. This was partly because of negative feelings towards German during World War I.

Spanish is now the most widely taught language after English in American high schools and colleges. In 2013, over 790,000 university students were taking Spanish classes. Spanish was the most popular foreign language in American colleges. About 50.6% of students taking foreign language courses chose Spanish. This was much more than French (12.7%), American Sign Language (7%), German (5.5%), Italian (4.6%), Japanese (4.3%), Chinese (3.9%), Arabic (2.1%), and Latin (1.7%). These numbers are still small compared to the total U.S. population.

Spanish Radio and Media

Spanish language radio is the biggest non-English broadcasting media. While other foreign language broadcasting went down, Spanish broadcasting grew from the 1920s to the 1970s.

The 1930s were a great time for Spanish radio. Its early success came from having many listeners in Texas and the Southwest. American stations were close to Mexico. This allowed entertainers and experts to move easily between countries. It also helped Hispanic radio leaders and advertisers be creative. In the 1960s and 1970s, fewer companies owned more stations. The industry had a magazine called Sponsor from the late 1940s to 1968. Spanish-language radio has influenced how Americans and Latinos talk about important topics like citizenship and immigration.

How Spanish Varies in the U.S.

Spanish in the U.S. has many different accents. English has a big impact on American Spanish. In many young Latino (or Hispanic) groups, it is common to mix Spanish and English. This is called Spanglish. It means switching between English and Spanish, or speaking Spanish with a lot of English influence.

The Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española (North American Academy of the Spanish Language) studies how Spanish changes in the United States. They also look at how English affects it.

Different Types of Spanish

Experts identify different types of Spanish spoken in the United States:

- Mexican Spanish: This is heard along the U.S.–Mexico border and throughout the Southwest. It is also common in Chicago and becoming widespread across the U.S. Standard Mexican Spanish is often taught as the main type of Spanish in the U.S.

- Caribbean Spanish: This is spoken by Puerto Ricans, Cubans, and Dominicans. It is heard a lot in the Northeast and Florida, especially in New York City and Miami.

- Central American Spanish: This is spoken by Hispanic people from Central American countries. These include El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. It is common in big cities in California and Texas, as well as Washington, D.C., New York, and Miami.

- South American Spanish: This is spoken by Hispanic people from South American countries. These include Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, and Bolivia. It is heard in major cities in New York State, California, Texas, and Florida.

- Colonial Spanish: This was spoken by descendants of Spanish colonists and early Mexicans. This was before the U.S. expanded and took over the Southwest.

- Californian (1769–present): Spoken in California, especially the Central Coast.

- Isleño Spanish (1783–present): Spoken in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana.

- Sabine River Spanish: Spoken in parts of Sabine and Natchitoches Parishes, Louisiana. Also in the Moral community west of Nacogdoches. It is almost gone now and came from rural Mexican Spanish.

- New Mexican Spanish: Spoken in central and north-central New Mexico and south-central Colorado. Also in border areas of Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico, and southeastern Colorado.

Many Spanish speakers in the U.S. speak it as a heritage language. This means they learned it from their family. Many of these speakers are "semi-speakers." They spoke Spanish when they were very young. But then they mostly switched to speaking English. They usually understand Spanish well. However, they might not have fully learned to speak it perfectly. Other fluent heritage speakers still use Spanish a lot in their families.

Semi-speakers sometimes make mistakes that native Spanish speakers usually don't. These mistakes are common for people learning Spanish as a second language. Semi-speakers often find Spanish classes hard. This is because the teaching materials are not right for them. They are either for English speakers or for fluent Spanish speakers.

Heritage speakers generally sound like native speakers when they pronounce words.

How Dialects Mix

Spanish in the U.S. often shows mixing of different types of Spanish. This happens in big cities where Hispanic people from different places live. For example, Salvadorans in Houston might change how they pronounce certain sounds. This is because they are around more Mexican speakers.

Los Angeles has its own unique Spanish. This happened because different types of Mexican Spanish speakers mixed there. Children of Salvadoran parents who grow up in Los Angeles usually speak this mixed Spanish. Other cities might also have their own special types of Spanish.

Voseo is a way of saying "you" using the word vos instead of tú. It is common among Honduran and Salvadoran immigrants in the U.S. The children of these immigrants tend to use tú more often. But they still sometimes use vos to show their Central American identity. Second-generation Salvadoran-Americans often use voseo verb forms with tú. This happens when they are unsure about their language in mixed groups. Third-generation Salvadoran-Americans have started using vos with tú verb forms. They use vos as a symbol of their identity.

Spanish speakers in the U.S. who are better at English tend to use the subjunctive mood less often. This is a grammar point. This also happens with Spanish speakers who have less education in Spanish.

Other things that happen with Spanish in the U.S. include:

- The word de (meaning "of") sometimes disappears in certain phrases. This is like in Spanish from the Canary Islands. For example, esposo Rosa instead of esposo de Rosa (Rosa's husband).

- Using Arabic-origin words more often than Latin-origin words that mean the same thing. For example, alcoba (from Arabic) for "bedroom" instead of habitación or dormitorio. This is common in American Spanish because it comes from Latin American Spanish, which was influenced by Spanish from Andalusia.

English Words from Spanish

Many common English words come from Spanish. Some even came from other languages but entered English through Spanish.

- Admiral (from Arabic)

- Avocado (from Nahuatl aguacatl)

- Aficionado

- Banana (from Wolof)

- Buckaroo (from vaquero)

- Cafeteria (from cafetería)

- Chili (from Nahuatl chīlli)

- Chocolate (from Nahuatl xocolatl)

- Cigar (from cigarro)

- Corral

- Coyote (from Nahuatl coyotl)

- Desperado (from desesperado)

- Guerrilla

- Guitar (from guitarra)

- Hurricane (from Taíno storm god Juracán)

- Junta

- Lasso (from lazo)

- Patio

- Potato (from patata)

- Ranch (from rancho)

- Rodeo

- Siesta

- Tomato (from Nahuatl tomatl)

- Tornado

- Vanilla (from vainilla)

How Spanish Sounds in the U.S.

Spanish in the U.S. often sounds a bit different because of English. For example, people who grew up speaking both languages in southern New Mexico often say the "r" sounds in a similar way. The rolled "r" sound is less common in northern New Mexico. This is because there is less contact with Spanish speakers from Mexico there.

The "b" and "v" sounds in Spanish can sometimes sound like the English "v" sound. This is especially true in the Southwest. The "j" sound in Spanish, which is usually a strong "h" sound, can sometimes sound like the English "h" sound.

The vowel sounds in Spanish can also be affected by English. For example, the "e" sound can sometimes be pronounced more forward in the mouth.

Many differences in how Spanish is pronounced in the U.S. are similar to differences in other Spanish dialects and varieties:

- Like in most of Hispanic America, the "z" and "c" (before "e" and "i") sounds are pronounced like "s". This is called seseo. It means not making a difference between these sounds. This is also common in parts of southern Spain.

- In Spain, especially in certain areas, the "s" sound is made with the tip of the tongue against the roof of the mouth. This can sound a bit like the English "sh" sound. In the Americas and in southern Spain, this "s" sound is more common.

- American Spanish usually has yeísmo. This means there is no difference in sound between "ll" and "y". Both are pronounced like the English "y" in "yes." This is also becoming common in Spain. However, some areas in the Andes mountains still keep the traditional "ll" sound.

- Most speakers from coastal areas might make the "s" sound at the end of a syllable sound like an "h" or even drop it completely. So, está ("s/he is") might sound like "ehtá" or "etá." This is like in southern Spain.

- The "g" (before "e" or "i") and "j" sounds are often pronounced like an "h" in Caribbean and other coastal dialects. This is also true in southern Mexico and most of southern Spain. In other dialects, it might be a stronger sound.

- In many Caribbean dialects, the "l" and "r" sounds can be mixed up at the end of a syllable. For example, caldo (broth) might sound like cardo (thistle). At the end of words, the "r" sound can become silent. This makes Caribbean Spanish sound a bit like English where "r" is not always pronounced. This also happens in Ecuador and Chile.

- In many Andean regions, the rolled "r" sound can be softer. It might sound more like the English "r" in "rat." This is common in areas with influence from native languages.

- In Puerto Rico, the "r" sound at the end of a syllable can sound like the English "r." For example, verso (verse) might sound like "verso" with an English "r." At the end of words, the "r" can be a rolled sound, a tap, or even silent.

- In most Colombian Spanish dialects, the "b," "d," and "g" sounds are pronounced more strongly after "n" or "l." For example, pardo (brown) sounds like "pard-o" instead of "par-do."

- At the end of a word, the "n" sound is often made in the back of the throat in Latin American Spanish. So pan (bread) might sound like "pang." This is very common in the Americas. Only a few regions keep the "n" sound like in Europe. This "n" sound is also common in southern Spain.

Spanish Words and Grammar in the U.S.

The words and grammar of U.S. Spanish show the influence of English. They also show how the language is changing and its roots in Latin America. One example of English influence is how American bilinguals use Spanish words. Spanish words that sound like English words (called cognates) can start to have similar meanings. For example, the Spanish word atender ("to pay attention to") and éxito ("success") have started to mean similar things to the English words "attend" and "exit" in American Spanish. Sometimes, English words are borrowed. This can make existing Spanish words have new meanings. For example, coche means "car" in older Spanish. In the U.S., it can also mean "coach" (like a sports coach).

Other things that happen include:

- Borrowed phrases from English are common. For example, correr para ("to run for") or aplicar para ("to apply for"). Also, soñar de instead of soñar con ("to dream of").

- Phrases with patrás (meaning "back") are widespread. For example, llamar patrás ("to call back").

- Spanish speakers in the U.S. tend to use estar more often instead of ser. Both mean "to be." This is part of a bigger trend in Spanish.

- Spanish speakers in the Southwest often use the future tense of verbs only for certain grammar moods. They use ir + a + infinitive (like "going to do something") to talk about future events.

- While voseo (using vos instead of tú for "you") was not common in U.S. Spanish, it has been brought by Central American immigrants. Children of these immigrants use voseo less than their parents. But the word vos remains a symbol of their identity.

- Spanish speakers who are better at English tend to use the subjunctive mood less often. This is a grammar point. This also happens with Spanish speakers who have less education in Spanish.

- The word de ("of") sometimes disappears in certain phrases. This is like in Spanish from the Canary Islands. For example, esposo Rosa for esposo de Rosa (Rosa's husband).

- Using Arabic-origin words more often than Latin-origin words that mean the same thing. For example, alcoba (from Arabic) for "bedroom" instead of habitación or dormitorio. This is common in American Spanish because it comes from Latin American Spanish, which was influenced by Spanish from Andalusia.

The Future of Spanish in the U.S.

Spanish is the most commonly spoken non-English language in the United States. New people moving to the U.S. is a key reason why Spanish continues to be used. This is because the children and grandchildren of earlier immigrants often switch to speaking English.

Spanish-language TV and radio, like Univisión, Telemundo, and Azteca América, help keep Spanish alive. However, they are also serving more people who speak both languages. Also, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) makes many American companies put labels on products in English, French, and Spanish. These are three of the official languages of the Organization of American States (OAS).

Besides businesses that have always served Spanish-speaking immigrants, more and more regular American stores are advertising in both Spanish and English. They also offer customer service in both languages. A common sign for these businesses is Se Habla Español, which means "Spanish Is Spoken."

The yearly State of the Union Address and other speeches by the U.S. President are translated into Spanish. This started with the Clinton administration in the 1990s. Also, politicians who don't have Hispanic backgrounds but speak Spanish will speak in Spanish to groups of voters who mostly speak Spanish. There are 500 Spanish newspapers, 152 magazines, and 205 publishers in the United States. Companies spent much more money on magazine and local TV ads for the Hispanic market from 1999 to 2003.

Historically, the languages of immigrants tend to disappear over generations. By the third generation, most people only speak English. This pattern has largely continued for recent immigrants, including Spanish speakers.

Spanish disappeared in several countries and U.S. territories during the 1900s. This happened in the Philippines and in Pacific Island countries like Guam, Micronesia, Palau, the Northern Marianas islands, and the Marshall Islands.

The English-only movement wants to make English the only official language of the United States. They try to pressure Spanish-speaking immigrants to learn English and speak it in public. Since universities, businesses, and many jobs use English, there is a lot of social pressure to learn English to get ahead. These pressures and rules contribute to Spanish being used less and people switching to English.

Generally, Hispanic people (13.4% of the U.S. population in 2002) are bilingual to some extent. A survey found that 19% of Hispanic people spoke only Spanish. 9% spoke only English. 55% had limited English skills. And 17% were fully bilingual in English and Spanish.

How well Spanish is passed down from parents to children is a better sign of its future in the U.S. than just counting speakers. Most second-generation Hispanic people speak English. But about 50% still speak Spanish at home. Two-thirds of third-generation Mexican Americans speak only English at home. A study in 1988 by Calvin Veltman looked at how much Spanish immigrants switched to English. He found that 40% of immigrants who came to the U.S. before age 14 stopped using Spanish. 70% of those who came before age 10 stopped using it. His studies suggest that a group of Spanish-speaking immigrants will mostly switch to English within two generations. Later census data also showed that Hispanic people were greatly adopting English.

Spanish Literature in the U.S.

American literature in Spanish dates back to 1610. That's when a Spanish explorer, Gaspar Pérez de Villagrá, published his long poem History of New Mexico. However, it wasn't until the late 1900s that Spanish, Spanglish, and bilingual books were easily found. These included poetry, plays, novels, and essays. They were available through different publishing companies and theaters. Cultural expert Christopher González says that Latina/o authors created new audiences for Hispanic Literature in the United States. Some of these authors include Oscar “Zeta” Acosta, Gloria Anzaldúa, Piri Thomas, Gilbert Hernandez, Sandra Cisneros, and Junot Díaz.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Idioma español en Estados Unidos para niños

In Spanish: Idioma español en Estados Unidos para niños

- List of Spanish-language newspapers published in the United States

- Biennial academic conference of Spanish in the United States

- Bilingual education

- Spanglish

- Spanish language in the Americas

- History of the Spanish language

- Languages of the United States

- Hispanic

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |