Bracero program facts for kids

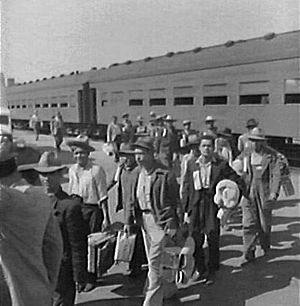

The Bracero program was a special agreement between the United States and Mexico. It started on August 4, 1942, during World War II. The word bracero comes from Spanish and means "manual laborer" or "someone who works with their arms."

This program allowed Mexican farmworkers to come to the U.S. to help with farming. It guaranteed them good living conditions, like clean places to stay and enough food. They were also promised a minimum wage of 30 cents an hour. The program also protected them from being forced into military service. Part of their pay was even saved in a special bank account in Mexico for when they returned home. The Bracero program lasted for 22 years, ending in 1964. It became the largest foreign worker program in U.S. history.

Contents

What Was the Bracero Program?

The Bracero Program was run by different U.S. government departments. These included the State Department and the Department of Labor. Its main goal was to solve the shortage of farmworkers during World War II. Many American workers had gone to fight in the war.

The program started in Stockton, California, in August 1942. It promised workers fair treatment. For example, braceros were not supposed to face discrimination or be kept out of "white" areas. However, this did not always happen. In Texas, the program was even stopped for several years in the 1940s. This was because Mexican workers faced discrimination and bad treatment.

Over its 22 years, the program offered work contracts to about 5 million braceros. They worked in 24 U.S. states. At first, only a small number of braceros came. But soon, both U.S. and Mexican employers relied heavily on them. Sometimes, people even paid bribes to get a work contract.

By 1951, a government report showed that having Mexican workers lowered the wages of American farmers. Still, the U.S. government wanted to continue the program. They also saw it as a way for Mexico to support the Allied forces in the war. From 1948 to 1964, about 200,000 braceros came to the U.S. each year.

Bracero Railroad Workers

Braceros also worked on railroads, not just in agriculture. Railroad workers did very hard manual labor. They expanded rail yards, laid tracks, and replaced old rails. This work was important for the war effort. It helped replace American railroad workers who had joined the military.

Railroad work contracts lasted until 1945. About 100,000 men worked as railroad braceros.

Braceros on the Southern Pacific Railroad

When the Bracero Program began in 1942, it included railroad jobs. The Southern Pacific railroad company needed many workers. They asked the government for permission to bring in workers from Mexico.

The rules for railroad braceros were similar to those for farmworkers. They were promised good wages, food, housing, and transportation. However, like farmworkers, railroad braceros often faced problems. They sometimes received unfair wages. Their living spaces were often poor, and food was scarce. They also experienced racial discrimination. These problems continued into the 1960s.

Bracero Wives and Families

The women in bracero families often stayed home in Mexico. They waited patiently for their husbands to return. Sometimes, families were worried about men leaving and not coming back. This made it hard for bracero men to get married before leaving.

Women were expected to keep writing letters and stay in touch. But bracero men in the U.S. did not always write back. Women were not supposed to show their fears about their relationships.

Women's Role in the Program

The Bracero Program offered a chance for men to earn more money. This could help them start a family or grow their businesses in Mexico. Because of this, both the Mexican and U.S. governments tried to get women to support the program.

Local Mexican officials knew that if a man joined the program, it often depended on his wife. Would she be willing to manage the family business alone? Workshops were held in villages across Mexico to teach women about the program. This encouraged them to support their husbands joining.

Government Control Over Families

Many bracero men wanted their families to join them in the U.S. They saved money and learned about American culture. They hoped to build a home for their families. The only way to share their plans was through letters.

These letters went through the U.S. postal system. At first, they were checked for complaints about working conditions. Later, if men wrote about bringing their families to the U.S. permanently, their letters were often stopped. The U.S. government feared that bracero families would settle permanently. The program was meant for temporary workers who would return to Mexico.

Program Changes and End

American farmers wanted a system that would bring in Mexican workers reliably. In 1951, President Truman signed Public Law 78. This law made the U.S. government responsible for the workers' contracts. Braceros were not allowed to go on strike. They also could not replace U.S. workers who were on strike.

A year later, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 was passed. This law made it a crime to knowingly hide or help undocumented immigrants. However, a rule called the "Texas Proviso" said that simply hiring undocumented workers was not considered "hiding" them. This law also led to the H-2A visa program, which still allows temporary foreign workers today.

To control the number of undocumented migrants, the U.S. government started "Operation Wetback" in 1954. This operation sent many illegal workers back to Mexico. Over a million Mexicans were sent back in the first year alone.

Unions and churches began to criticize the Bracero Program. They said it hurt American farmworkers. In the late 1950s, the Department of Labor started closing bracero camps. They also set new minimum wage rules. In 1959, they demanded that American workers get the same wages and benefits as braceros.

In 1961, President Kennedy signed an extension of Public Law 78. This law guaranteed U.S. workers the same benefits as braceros. After this, the number of bracero workers dropped sharply. In 1963, the House of Representatives voted against extending the program. The Bracero Program officially ended in 1964.

Braceros and Worker Strikes

Braceros often faced unfair conditions. They found ways to resist and try to improve their lives. Over two dozen strikes happened in the first two years of the program.

Reasons for Bracero Discontent

Braceros came to the U.S. to find work and improve their lives. But they had little control over their living and working conditions. Farmers controlled their pay, work hours, and even transportation.

The agreements said that employers should pay for travel and provide good housing and medical care. They also promised that braceros would get the same services as other farmworkers. But employers often did not keep these promises. Braceros had no say in decisions about their working conditions.

Poor food was a common complaint. Workers often disliked the cold sandwich lunches. Pay was also very low and often delayed. Sometimes, workers were paid less than the promised 30 cents per hour.

Wage Problems

Despite their contracts, braceros often faced unfair wages. Their pay was sometimes held back or given out inconsistently. Both railroad and farm braceros were often shortchanged.

The U.S. and Mexico had agreed to save 10% of bracero wages in Mexican bank accounts. This money was meant for the workers when they returned home. However, many braceros never received these savings. It is estimated that about $32 million was "transferred" but went missing or was not accessible. Even today, former braceros are fighting to get the money they are owed.

Bracero Strikes in the Northwest

In the Northwest U.S., there were fewer Mexican government inspectors. This made it harder to check on pay and working conditions. Farmers in the Northwest also formed groups to keep wages low and prevent unions. They used police and even the National Guard to keep "order."

However, braceros in the Northwest were farther from the Mexican border. This made it harder for employers to threaten them with deportation. It was also harder for braceros to run away from their contracts and blend into a Mexican-American community.

Because of these challenges, the Mexican consulates in Salt Lake City and Portland encouraged workers to protest. They also spoke up for the workers. This led to a situation where braceros in the Northwest felt they had to strike to be heard.

Braceros found clever ways to resist. They would sometimes put rocks in their harvest bags to make them heavier and get paid more. Strikes were more successful during cold weather or when crops needed to be harvested quickly. This showed employers that it was better to negotiate than to deport workers.

Braceros also faced discrimination and segregation in labor camps. Some growers built separate camps for white, Black, and Mexican workers. Conditions were often terrible and unsanitary. For example, in 1943, 500 braceros in Oregon got food poisoning. The Mexican government had to step in to improve food quality.

After the Program

After the Bracero Program ended in 1964, the U.S. tried a new program called A-TEAM in 1965. This program aimed to fill farmworker shortages and provide summer jobs for teenagers. Over 18,000 high school students were recruited. But only about 3,300 actually worked in the fields. Many quickly quit or went on strike because of the bad working conditions, heat, and poor housing. The program was canceled after one summer.

Importance and Effects

The Bracero Program had a big impact on both the U.S. and Mexico.

The Catholic Church in Mexico was against the program. They worried about families being separated. They also feared that braceros would be exposed to bad habits or other religions in the U.S.

Labor unions in the U.S. also opposed the program. They believed it kept wages low for American farmworkers. Leaders like César Chávez and Dolores Huerta fought against the program. They argued that bracero labor hurt local workers.

A terrible bus crash in California in 1963 killed 31 braceros. This accident highlighted the harsh conditions workers faced. It led many activist groups to strongly oppose the program. The end of the Bracero Program helped lead to the rise of the United Farm Workers. This group, led by César Chávez, Gilbert Padilla, and Dolores Huerta, changed American migrant labor.

The program left a lasting mark on the economies and migration patterns of both countries. While many critics pointed out the poor conditions, many braceros found opportunities. They saved money, bought new tools, and returned home with a greater sense of dignity.

A 2018 study found that the Bracero Program did not harm American-born farmworkers' jobs or wages. The study also found that ending the program did not raise wages or employment for American-born farmworkers.

In Popular Culture

The Bracero Program has been featured in many songs and films:

- Woody Guthrie's poem "Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)" remembers the deaths of 28 braceros in a 1948 plane crash. Many folk artists have recorded this song.

- Protest singer Phil Ochs wrote a song called "Bracero" about the exploitation of Mexican workers.

- The 1949 film Border Incident also explores the issue.

- The 2010 documentary Harvest of Loneliness tells the story of the program. It includes interviews with former braceros.

Exhibitions and Collections

In 2009, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History had an exhibition called "Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program, 1942–1964." It showed photographs and oral histories from bracero workers and their families. This exhibition helped people understand the history of Mexican Americans and today's discussions about guest worker programs. The exhibition later traveled to several U.S. states.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Programa Bracero para niños

In Spanish: Programa Bracero para niños

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |