Chichimeca War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Chichimeca War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas and Mexican Indian Wars | |||||||

1580 drawing showing a battle near San Francisco Chamacuero in Guanajuato |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Chichimeca Confederation

|

Allies & auxiliaries:

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

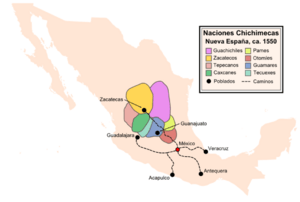

The Chichimeca War (1550–1590) was a long fight between the Spanish Empire and a group of native peoples called the Chichimeca Confederation. This war happened in what is now central Mexico, a large area the Spanish called La Gran Chichimeca. The main battles took place in the Bajío region.

This war was the longest and most costly military campaign the Spanish Empire fought against native people in Mesoamerica. It lasted for 40 years. In the end, the Spanish made several peace treaties to stop the fighting. This led to the Chichimeca people slowly joining the society of New Spain.

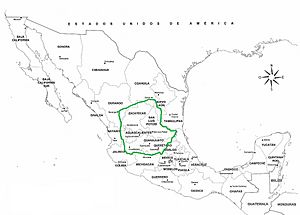

The Chichimeca War started eight years after another conflict called the Mixtón War. Some people see it as a continuation because fighting didn't really stop in between. This time, the Caxcanes, who fought against the Spanish in the Mixtón War, were now on the Spanish side. The war was fought in areas that are now the Mexican states of Zacatecas, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, Jalisco, Queretaro, and San Luis Potosí.

Contents

Why the War Started

The war began because of silver. In 1546, native people near Zacatecas showed a Spaniard named Juan de Tolosa some silver ore. News of this discovery spread quickly across New Spain. Many Spaniards moved from southern Mexico to Zacatecas, which was in the heart of La Gran Chichimeca.

Soon, new silver mines were opened in places like San Martín, Chalchihuites, and Fresnillo. The Chichimeca nations were unhappy about the Spanish moving onto their lands. Spanish soldiers also started raiding native areas to capture people and force them to work as slaves in the mines.

To connect and supply these mines, new roads were built through Chichimeca lands from Querétaro and Jalisco. These roads were used by caravans carrying valuable goods. Chichimeca warriors often attacked these caravans, seeing them as targets for their raids.

Who Were the Chichimecas?

The Chichimecas were groups of people who moved around a lot, living in the large desert area of central Mexico. This area was about 160,000 square kilometers (62,000 square miles). The Chichimecas mostly hunted animals and gathered plants for food. They ate things like mesquite beans, parts of agave plants, and cactus fruits. In some good areas, they also grew corn and other crops.

It's hard to know exactly how many Chichimecas there were, but estimates suggest between 30,000 and 60,000 people. They lived in simple shelters or caves and moved often to find seasonal foods and good hunting spots. The Chichimecas called themselves "Children of the Wind" and lived closely with nature. The Spanish noticed that both men and women wore little clothing, had long hair, and painted their bodies. Some Spanish writers wrongly accused them of cannibalism to make them seem like savages.

The Chichimeca Confederation was made up of four main groups: the Guachichiles, Pames, Guamares, and Zacatecos. These groups didn't have one central government. Instead, they were more like independent states. Their territories often overlapped, and different Chichimeca warriors would join together for raids.

Guachichiles

The Guachichiles lived around the area that became the city of San Luis Potosí. They seemed to be the largest group and were often the leaders of the Chichimecas. Their name meant "Red Colored Hair" because they used a red pigment on their hair, skin, and clothes. They lived close to the silver road between Querétaro and Zacatecas and were the most feared raiders.

Pames

The Pames lived north of present-day Querétaro and south and east of the Guachichiles. They were the least warlike of the Chichimecas. They had adopted some customs from more settled native groups.

Guamares

The Guamares mostly lived in what is now Guanajuato. They might have had more political unity than other Chichimecas. One writer called them the most "treacherous and destructive" and "astute" of all the Chichimecas.

Zacatecos

The Zacatecos lived in the Mexican states of Zacatecas and Durango. They had fought against the Spanish in the earlier Mixtón War, so they were experienced fighters. Some Zacatecos grew corn, while others moved around.

Chichimeca Fighting Style

The Chichimecas' nomadic way of life made them hard for the Spanish to defeat. Their main weapon was the bow and arrow. One person who saw them fight said the Zacatecos were "the best archers in the world." Their bows were short, and their arrows were long, thin, and tipped with obsidian. Obsidian is a volcanic rock that can be sharper than a modern razor. Even though obsidian arrows were fragile, they could go through Spanish armor. Soldiers often preferred buckskin armor over chain mail because obsidian arrows could pierce the links of the mail.

The Chichimecas were very skilled with their bows. There are stories of them shooting an orange in the air and hitting it with so many arrows that it fell in tiny pieces. Another story tells of an arrow going through a horse's head, its armor, and into a soldier's chest, killing both.

Because they moved around, the Chichimecas were very fast and knew the rough, cactus-filled land well. They could hide easily. They could also cut off Spanish supplies and destroy livestock, which made it hard for the Spanish, who relied on these things. The Chichimecas attacked in small groups, from five to 200 warriors. In one battle, 50 Zacateco warriors reportedly killed 200 Spanish soldiers. They always had enough warriors for raids because the valuable Spanish supplies attracted fighters from far away.

As the war went on, both sides improved their fighting methods. The Chichimecas sent spies into Spanish towns to learn their plans. They also set up lookouts and scouts. Before big attacks, they would kill or steal horses and other animals to make the Spanish fight on foot. When they attacked, they used a terrifying tactic. The Guachichil warriors would dress up like strange animals using animal heads and paint. Then they would yell like crazy beasts, making the Spanish horses and livestock panic.

The Spanish started building many forts and hired mercenaries. They also tried to use as many slaves as they could. Chichimeca battle tactics mostly involved ambushes and quick raids. Groups of 40 to 50 warriors were common. During the war, the Chichimecas learned to ride horses and use them in battle. This was one of the first times the Spanish in North America faced native warriors on horseback. The Spanish had an advantage with their horses and other pack animals, which were new to the Americas.

How the War Unfolded

The conflict was much harder and lasted longer than the Spanish expected. Fighting started in late 1550 when Zacatecos attacked supply routes of the Purépecha. A few days later, they attacked Spanish settlements near modern-day Zacatecas. In 1551, the Guachichiles and Guamares joined in. They killed 14 Spanish soldiers at an outpost near San Miguel de Allende. Other raids killed 120 Spanish people in just a few months.

In 1553 and 1554, many wagon trains on the road to Zacatecas were attacked. All the Spanish travelers were killed, and goods worth huge amounts of money (32,000 and 40,000 pesos) were stolen or destroyed. To compare, a Spanish soldier's yearly salary was only 300 pesos. By the end of 1561, it was thought that over 4,000 Spaniards and their native allies had been killed by the Chichimecas. Prices for food and other goods in Zacatecas doubled or tripled because it was so dangerous to transport them. In the 1570s, the rebellion spread, and Pames began raiding near Querétaro.

The Spanish government first tried to use both rewards and punishments to stop the war. But when that failed, in 1567, they decided on a policy of "war of fire and blood." This meant they promised death and slavery to the Chichimecas. One of the main goals for the Spanish was to keep the roads open to Zacatecas and its silver mines. The most important road was the Camino Real from San Miguel de Allende. Without these roads, the Spanish couldn't pay for the war or support their settlements.

To protect the roads, they built many new forts called presidios. These forts had Spanish soldiers and native allied soldiers. The Spanish also encouraged more people to settle in new areas, which became cities like Celaya, León, Aguascalientes, and San Luis Potosí.

The first main forts were built in San Miguel in 1562 and San Felipe in 1563. But even with these forts, the Chichimecas continued to succeed. By 1571, most Chichimeca groups were raiding towns and important economic routes. A letter from a priest in 1571 mentioned that Zacatecos attacked a Spanish settlement, causing a lot of damage.

After 1560, and especially in the 1570s, the Chichimecas started attacking towns more often. In a letter from 1576, the viceroy of New Spain told King Felipe II of Spain that they needed more soldiers and money to fight the war. He also said that they couldn't keep fighting because the cost was too high. They didn't have enough weapons, soldiers, or food because their livestock was constantly being stolen or killed.

Even when the royal treasury fully paid for the war, the Chichimecas attacked with even greater force from 1575 to 1585. In 1581, the viceroy wrote to King Felipe II that the situation was so bad that many mines in Zacatecas were closed because of the native attacks. The Spanish didn't have more success even when they tried tricks. The main royal road was destroyed, and no Spanish fort in Guachihile territory was left standing.

Having more Spanish soldiers in the Gran Chichimeca didn't always help. Soldiers often made extra money by raiding and taking slaves, which made the Chichimecas even angrier. Even with more Spanish settlers and soldiers, the Spanish were always short of fighters compared to the growing number of Chichimeca raiders. Often, their forts only had three Spaniards. Even with help from other native allies like the Caxcans, Purépechas, and Otomis, the Spanish couldn't match the Chichimeca Confederation. These native allies were given Spanish land and were allowed to ride Spanish horses and carry Spanish swords, which was usually forbidden for native allies.

Buying Peace

As the war continued without stopping, it became clear that the Spanish policy of "fire and blood" had failed. The royal treasury was running out of money because of the war. Church leaders and others who had first supported the harsh war policy now questioned it. Many started to believe that the mistreatment and enslavement of Chichimeca women, children, and men by the Spanish was the real cause of the war. In 1574, the Dominican Order declared that the Chichimeca War was unfair and caused by Spanish aggression. So, to end the conflict, the Spanish began to change their approach to buy peace from the Chichimecas and help them join Spanish society.

In 1584, the Bishop of Guadalajara suggested a "Christian solution" to the war. This idea was to build new towns with priests, soldiers, and friendly native people. These towns would slowly help the Chichimecas become Christians. The Viceroy, Alvaro Manrique de Zuniga, followed this idea in 1586. He started removing many Spanish soldiers from the border areas, believing they caused more problems than they solved.

The Viceroy began talking with Chichimeca leaders. He offered them tools, food, clothing, and land to encourage them through "gentle persuasion." He also stopped further military attacks that were failing. A key person in these talks was Miguel Caldera, a captain who was part Spanish and part Guachichile. Starting in 1590, and for many years after, the Spanish began a program called "Purchase for Peace." They sent large amounts of goods north to be given to the Chichimecas. In 1590, the Viceroy announced that the program was a success, and the roads to Zacatecas were safe for the first time in 40 years.

The next step, in 1591, was for a new Viceroy, Luis de Velasco, with help from Caldera, to convince 400 families of Tlaxcalan Indians to move. The Tlaxcalans were old allies of the Spanish. They set up eight settlements in Chichimeca areas. They served as Christian examples to the Chichimecas and taught them how to raise animals and farm. In return for moving, the Tlaxcalans received special benefits from the Spanish. These included land, freedom from taxes, the right to carry weapons, and supplies for two years. The Spanish also tried to stop slavery on Mexico's northern border by arresting members of the Carabajal family and Gaspar Castaño de Sosa. A very important part of their plan was to convert the Chichimecas to Catholicism. The Franciscans sent priests to the border to help with this peace effort.

The "Purchase for Peace" program worked to reduce the fighting. Most of the Chichimecas gradually settled down and became Catholic, or at least seemed to be Catholic.

Why This War Was Important

The Spanish policy to make peace with the Chichimecas had four main parts:

- Negotiating peace agreements.

- Welcoming, rather than forcing, conversion to Catholicism.

- Encouraging native allies to settle on the border to be good examples.

- Providing food, goods, and tools to potentially hostile native groups.

This approach set the pattern for how the Spanish would try to bring native peoples into their society on their northern border. The main ideas of the "Purchase for Peace" policy continued for almost 300 years. However, it wasn't always as successful later on, especially when dealing with groups like the Apaches and Comanches.

Chichimecas Today

Over time, most of the Chichimeca people changed their ethnic identities. They became part of the Catholic population and joined mainstream Mexican society, both before and during the Mexican War of Independence. Many Guachichil people moved to larger cities like Zacatecas or Aguascalientes, and some even went to areas that are now part of the United States, like California, Colorado, and Texas.

The Wixárika, also known as the Huicholes, are believed to be descendants of the Guachichiles. About 20,000 of them live in a remote area between Jalisco and Nayarit. They are known for keeping their language, religion, and culture alive.

There are about 10,000 speakers of the Pame languages in Mexico, mostly in a remote area of southeastern San Luis Potosí. They are mostly Catholic but still practice their traditional religion and customs. Another group of about 1,500 Chichimeca Jonaz live in the state of Guanajuato.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra Chichimeca para niños

In Spanish: Guerra Chichimeca para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |