Morisco facts for kids

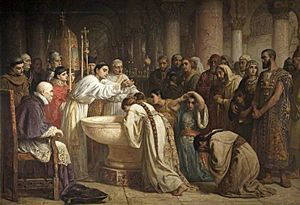

Moriscos (pronounced: moh-REES-kohs) were people in Spain who used to be Muslims. The Roman Catholic Church and the Spanish rulers told them they had to become Christian or leave the country. This happened in the early 1500s after Spain made it illegal to openly practice Islam. Before this, Muslims who lived under Christian rule were called mudéjars.

The rulers of Spain and Portugal didn't trust the Moriscos. They worried the Moriscos might help the Ottoman Empire invade after the Fall of Constantinople. So, between 1609 and 1614, they started to force them out of Spain. The biggest expulsions happened in the eastern Kingdom of Valencia. We don't know exactly how many Moriscos were in Spain before this, but many were forced to leave. Most of them settled in the Ottoman Empire or the Kingdom of Morocco. The last time Moriscos were punished for secretly practicing Islam was in Granada in 1727.

In Spanish America, the word morisco was also used for people of mixed race. It described children born from Spanish men and women who had both African and European family backgrounds.

Contents

Who Were the Moriscos?

The word morisco started being used in the early 1500s for Muslims who became Christian. At first, Moriscos often called themselves simply muslimes (Muslims). Later, they might have started to accept the name. Today, the word is widely used in books and other languages.

The word morisco comes from an older Spanish word for "Moorish." In the Middle Ages, "Moor" generally meant "Muslim" or "Arabic-speaker." After the forced conversions, Christians sometimes called this group "new Christians" or "new converts."

By 1517, morisco became a specific term for former Muslims in Granada and Castile. It was a bit of a negative word, but it became the standard way to refer to all former Muslims in Spain.

In Spanish America, morisco also meant a person of mixed race. It described a child born from a Spaniard and a mulatta (a person with both Spanish and African ancestors). This term appeared in old marriage records and paintings from the 1700s.

How Many Moriscos Were There?

It's hard to know the exact number of Moriscos because there wasn't a perfect count. Also, many Moriscos tried to hide their background to seem like regular Spanish people.

Historians generally agree that about 275,000 Moriscos were forced out of Spain in the early 1600s. Some historians believe there were around 300,000 to 330,000 Moriscos in the early 1500s. Other studies suggest there might have been as many as 500,000 just before the expulsions. Some experts think that about 40% of Moriscos avoided being expelled, and another 20% managed to return to Spain later.

Moriscos in Granada

The Emirate of Granada was the last Muslim kingdom in Spain. It surrendered in 1492 after a long war. Granada became part of Castile and had a large Muslim population, about 250,000 to 300,000 people. At first, the Treaty of Granada promised that Muslims could keep their religion. But a church leader, Cardinal Cisneros, tried hard to convert them. This led to a series of rebellions.

After the rebellions were put down, Muslims in Granada had a choice: become Christian, be enslaved or killed, or leave. Leaving was often very difficult. Soon after, all Muslims in Granada were officially Christian.

Even though they converted, many Moriscos kept their old customs. This included their language (Arabic), names, food, clothes, and some ceremonies. Many secretly practiced Islam while publicly acting Christian. Spanish rulers became stricter to stop these practices. In 1567, King Philip II ordered Moriscos to give up their customs, clothes, and language. This led to more revolts from 1568 to 1571. After this rebellion was crushed, the authorities decided to move Moriscos from Granada to other parts of Castile. About 80,000 to 90,000 Granadan Moriscos were sent to different towns.

Moriscos in Valencia

In 1492, the Kingdom of Valencia had the second-largest Muslim population in Spain. Many nobles in Valencia allowed Islam to be practiced until the 1520s.

In the 1520s, a rebellion called the Revolt of the Brotherhoods broke out among Christians in Valencia. These rebels disliked Muslims and forced many Valencian Muslims to become Christian. After the rebellion, King Charles V decided that these forced conversions were valid. He then ordered all remaining Muslims to convert.

After these forced conversions, Valencia was where Islamic culture remained strongest. Some nobles even let their Moriscos live "almost openly as Mohammedans." Arabic was still spoken, and Valencian Moriscos taught others about Arabic and religious texts.

Moriscos in Aragon and Catalonia

Moriscos made up about 20% of the population in Aragon. They lived mostly near the Ebro river. Unlike Moriscos in Granada and Valencia, they didn't speak Arabic. They were allowed to practice their faith more openly because they were vassals (like tenants) of the nobles.

In Catalonia, Moriscos were less than 2% of the population. They mostly spoke Catalan, and some spoke Castilian-Aragonese.

Moriscos in Castile and Andalusia

The Kingdom of Castile included Granada, Extremadura, and parts of Andalusia. Moriscos here were more spread out, except in a few towns where they were the majority. Moriscos in Castile were very integrated and often hard to tell apart from other Catholics. They didn't speak Arabic, and many were truly Christian.

However, when Moriscos from Granada were moved to Castile after their rebellion, it changed things. The new arrivals were more visibly different. The town of Hornachos was special because almost all its people were Moriscos. They openly practiced Islam and were known for being independent. Because of this, the "Hornacheros" were among the first Castilian Moriscos to be expelled. They were even allowed to leave with their weapons, like an undefeated army. They later founded the Republic of Salé in Morocco.

Moriscos in the Canary Islands

The Moriscos in the Canary Islands were different. They weren't descendants of Spanish Muslims. They were Muslims from North Africa who had been captured or taken prisoner. They gradually became Christian, some even helping in raids against their old homelands. When the king stopped these raids, they lost touch with Islam. They became a big part of the islands' population. They protested their Christianity and avoided the expulsions that happened in Europe.

Religion of the Moriscos

Christianity

Many Moriscos chose to become Christian. In Granada, some Moriscos were even killed by Muslims for refusing to give up Christianity. In the 1500s, Christian Moriscos in Granada chose the Virgin Mary as their special saint. They wrote Christian books that focused on her.

Islam

Since they were forced to convert, most Moriscos still believed in Islam. But it was dangerous to practice it openly, so they did it secretly. A religious opinion, called the "Oran fatwa," spread in Spain. It said that Muslims could pretend to be Christian if it was necessary to survive. This fatwa allowed them to do things normally forbidden in Islam, like eating pork or drinking wine, as long as they still believed in Islam in their hearts.

A secret Muslim writer, known as the "Young Man of Arévalo," wrote about his travels in Spain. He met other secret Muslims and described their religious practices. He wrote about secret group prayers and collecting money for the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). He hoped that Islam could be fully practiced again soon. He wrote his books in Spanish using Arabic letters (called aljamiado).

Copies of the Qur'an from the Morisco period have been found. Many were not full copies but smaller parts, which were easier to hide. Other surviving Islamic texts include stories of prophets and Islamic law books.

Moriscos also likely wrote the Lead Books of Sacromonte. These were texts in Arabic that claimed to be ancient Christian books. When they were found in the 1590s, Christians in Granada were excited. However, some historians think Moriscos wrote these texts to secretly blend Islamic ideas into Christianity. The texts seemed Christian but avoided ideas like the Trinity (God as three persons), which Muslims find offensive. Instead, they said, "There is no god but God and Jesus is the Spirit of God," which is very close to the Islamic declaration of faith.

This situation was similar to the Marranos, who were secret Jews living in Spain at the same time.

Timeline of Events

The Reconquista and Early Muslims

- Further information: Reconquista, Mudejar, and Treaty of Granada

Islam arrived in Spain in the 700s. By the 1100s, about 5.5 million Muslims lived in Spain, which they called "Al-Andalus." Over the next few centuries, Christian kingdoms from the north slowly took back land in a process called the reconquista. By the late 1400s, the number of Muslims in Spain had dropped to about 500,000 to 600,000 out of a total population of 7 to 8 million. About half of these Muslims lived in Granada, the last independent Muslim state.

The Christians called the defeated Muslims who lived under their rule Mudéjars. Before the Reconquista was finished, these Muslims were usually allowed to practice their religion as part of their surrender agreements. For example, the Treaty of Granada promised religious freedom to the Muslims of Granada.

Forced Conversions

When the first archbishop of Granada, Hernando de Talavera, wasn't very successful at converting Muslims, Cardinal Cisneros took stronger actions. He forced conversions, burned Islamic books, and punished many Muslims. In response, Granada's Muslim population rebelled in 1499. This revolt lasted until 1501, giving the Spanish authorities an excuse to break the promises of the Treaty of Granada.

In 1501, Spanish authorities gave Muslims in Granada an ultimatum: convert to Christianity or be expelled. Most converted to avoid losing their property and children. Many kept their traditional clothes, spoke Arabic, and secretly practiced Islam. The 1504 Oran fatwa gave religious permission for secretly practicing Islam while outwardly acting Christian. In 1502, Queen Isabella I of Castile officially ended religious tolerance for Islam in all of Castile. In 1508, traditional Granadan clothing was banned.

However, King Ferdinand of Aragon continued to allow a large Muslim population in his territory. Nobles in Aragon depended on Muslim workers, so they tolerated Islam. But in the 1520s, a rebellion in Valencia forced many Muslims to be baptized. The Inquisition and the king decided these forced conversions were valid. Finally, in 1526, King Charles V ordered all Muslims in Aragon to convert to Catholicism or leave Spain.

After the Conversion

For the first few decades after the conversions in Granada, former Muslim leaders acted as a link between the Spanish rulers and the Morisco people. Some religious tolerance was still seen in the early 1500s. These leaders helped collect taxes and defended Moriscos in royal courts. Some became true Christians, while others secretly remained Muslim. Islamic faith was stronger among the poorer Moriscos.

Outside Granada, Christian lords often defended their Morisco workers. In areas with many Moriscos, like Valencia, former Muslims were important for farming and crafts. Because of this, Christian lords often protected their Moriscos, sometimes even getting into trouble with the Inquisition.

In 1567, Philip II ordered Moriscos to give up their Arabic names, traditional clothes, and the Arabic language. Morisco children were to be taught by Catholic priests. This led to the Morisco Revolt in the Alpujarras from 1568 to 1571.

The Expulsion

King Philip III decided to expel the Moriscos from Spain between 1609 and 1614. They were told to leave or face death and losing their property. They could not take money, jewels, or valuables, only what they could carry. About 270,000 to 300,000 Moriscos were expelled, which was about 4% of Spain's population.

Most were expelled from Aragon, Catalonia, and Valencia. Valencia was hit hardest because it had large, strong Morisco communities. Some historians say that the economy of Spain's eastern coast suffered greatly because they lost so many skilled Morisco workers. Many villages were completely empty.

In Castile (including Andalusia and Murcia), the expulsion was less severe. Moriscos there were more integrated and had support from local Christians and authorities. Also, the Moriscos from Granada had been spread out across Castile, making them harder to find and expel.

Even though many Moriscos were sincere Christians, adult Moriscos were often thought to be secret Muslims. Expelling their baptized children was a problem because it was illegal to send Christians to Muslim lands. Some suggested separating children from their parents, but there were too many. So, the official destination for those expelled was often France. About 150,000 Moriscos were sent there. Many then moved to other Christian lands like Italy or Sicily, or to Constantinople. Some historians believe that as many as a quarter of those expelled eventually returned to Spain.

Most of the refugees settled in Muslim lands, mainly in the Ottoman Empire (Algeria, Tunisia) or Morocco. However, they often struggled because they spoke Spanish and had Spanish customs.

Moriscos and Other Countries

French Protestants (Huguenots) talked with Moriscos about plans against the Spanish rulers in the 1570s. There were plans for Moriscos and Huguenots to attack Spanish Aragon, with help from the king of Algiers and the Ottoman Empire. But these plans failed. In 1576, the Ottomans planned to send a fleet to Spain to help a Morisco uprising, but the fleet never arrived.

Spanish spies reported that the Ottoman Emperor Selim II wanted to attack Malta and then Spain. He reportedly wanted to start a Morisco uprising. Also, about "four thousand Turks and Berbers had come into Spain to fight alongside the rebels in the Alpujarras." This was a very brutal war. After the Spanish forces won, they expelled about eighty thousand Moriscos from the Granada Province. This uprising made the Spanish rulers much stricter, and the Spanish Inquisition increased its persecution of Moriscos.

Moriscos in Literature

The writer Miguel de Cervantes, famous for Don Quixote, wrote about Moriscos in his books. In the first part of Don Quixote, a Morisco translates an Arabic "history" that Cervantes is publishing. In the second part, after the expulsion, a character named Ricote is a Morisco. He admits that their expulsion was right, even though his daughter, Ana Félix, is a sincere Christian who suffers in North Africa.

In the late 1500s, Morisco writers tried to show that their culture was part of Spain. They wrote about early Spanish history where Arabic-speaking Spaniards played a good role. One important work was Verdadera historia del rey don Rodrigo by Miguel de Luna.

What Happened After?

Many Moriscos joined the Barbary Corsairs, who were pirates based in North Africa. They attacked Spanish ships and coasts. In the Corsair Republic of Sale, they became independent and made money from trade and piracy.

Morisco soldiers also served the Moroccan sultan. They crossed the Sahara Desert and conquered Timbuktu in 1591. Their descendants formed a group called the Arma. Moriscos also joined Ottoman armies in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt.

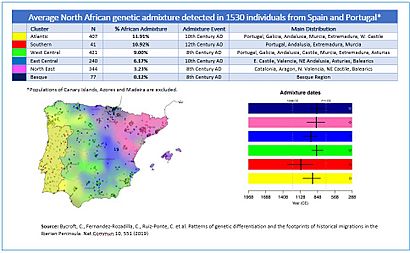

Modern studies of people's genes show that many modern Spaniards have North African ancestors. This is thought to be from the time of Muslim rule and from the Moriscos who stayed in Spain and avoided expulsion.

Moriscos Remaining in Spain

It's hard to know how many Moriscos stayed in Spain after the expulsion. Some early estimates said very few, but recent studies suggest more remained than previously thought. The expulsion was not equally successful everywhere.

For example, in Villarrubia de los Ojos in southern Castile, the entire Morisco population was targeted for expulsion three times. But they managed to avoid it or return, often hidden by their non-Morisco neighbors. Many similar cases happened across Spain, where Moriscos were protected and returned from North Africa, Portugal, or France.

A study in Andalusia found that the expulsion there was not very effective. Local authorities and people resisted it. Many Moriscos returned from North Africa. When King Philip IV came to power, he ordered that returning Moriscos should not be punished unless they caused big problems.

An investigation in 2012 showed that thousands of Moriscos remained in Granada province alone. They survived both the first expulsion in 1571 and the final one in 1604. They hid their true origins. Surprisingly, by the 1600s and 1700s, many of these families became very rich by controlling the silk trade and holding public jobs. Most of them eventually blended into the main culture. A small group of secret Muslims was punished by the Inquisition in 1727, but they received light sentences. They kept their identity alive until the late 1700s.

The expulsion in Extremadura was also seen as a failure, except for the quick expulsion of the Hornacheros. Moriscos in Extremadura received a lot of support from local authorities and society. Many avoided being deported, and whole communities temporarily moved to Portugal only to return later. So, the expulsion between 1609 and 1614 did not remove all Moriscos from the region.

Similar things happened in Murcia, where Moriscos were a majority in many areas. They were well-integrated with strong family and neighborly ties. This made it possible for most expelled Moriscos to return. By 1622, authorities no longer bothered them.

The expulsion was much more effective in eastern Spain (Catalonia, Aragon, and Valencia). Here, the expulsion was accepted more fully, and fewer Moriscos avoided it or returned. This is why Spain as a whole was not as affected by the expulsion, but Valencia was devastated economically and never fully recovered its power.

Some communities in rural Spain (like in Murcia and Albacete) seem to have kept traces of their Islamic or Morisco identity. They secretly practiced a simpler form of Islam as late as the 1900s and kept Morisco customs and some Arabic words in their speech.

Moriscos and Genetics

Moriscos were the last group in Spain who identified with Muslim conquerors from North Africa. Studies of modern Spanish and Portuguese people's genes show higher levels of North African ancestry than in other parts of Europe. This is generally linked to Islamic rule and settlement in Spain. This North African ancestry is higher in the South and West of Spain, especially in parts of Andalusia, Extremadura, and Western Castile. It is mostly absent from northeastern Spain and the Basque country. The uneven spread of this ancestry is explained by how much Islamic influence there was in an area, and how successful the Morisco expulsions were in different regions.

Notable Moriscos

- Aben Humeya: Leader of the Morisco revolt.

- Young Man of Arévalo: A secret Muslim writer in Spain.

- Abdelkader Pérez: Moroccan ambassador to England.

- Joan Malet: A Catalan Morisco who hunted witches.

- Leo Africanus: A Berber diplomat and writer.

See also

In Spanish: Morisco para niños

In Spanish: Morisco para niños

- Al-Andalus: The part of Spain under Islamic rule.

- Aljamiado: A Romance language written with Arabic letters.

- Castas: Mixed-race groups in Spanish America.

- Conversos: Baptized Jews and Muslims in Spain.

- Crypto-Islam: Secretly practicing Islam.

- Forced conversion: Being made to change religion.

- Hornachos: A village mostly inhabited by Moriscos.

- Marranos: Secret Jews in Spain.

- Moors: Muslim people from the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa.

- Morisco Revolt: A rebellion by Moriscos.

- Mudéjar: Muslims living under Christian rule.

- Reconquista: The Christian reconquest of Spain.

- Spanish Inquisition: A powerful religious court in Spain.

- Treaty of Granada (1491): An agreement that initially protected Muslim rights in Granada.

Images for kids

-

Monuments in Sale, where many Moriscos found refuge and founded the Republic of Salé.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |