Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain facts for kids

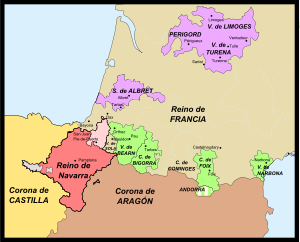

The forced conversions of Muslims in Spain happened when the Spanish kings made laws to ban the religion of Islam in their lands. This happened in different parts of Spain during the early 1500s. First, the Crown of Castile made these laws between 1500 and 1502. Then, the Kingdom of Navarre followed in 1515–1516. Finally, the Crown of Aragon did the same from 1523 to 1526.

After Christian kingdoms took back control of Spain (a time called the Reconquista) in 1492, there were about 500,000 to 600,000 Muslims living there. At first, Muslims living under Christian rule were called "Mudéjars." They were allowed to practice Islam openly. But in 1499, a powerful church leader named Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros started forcing Muslims in Granada to become Christians. He used harsh methods like torture and jail. This led to a rebellion by Muslims.

The rebellion was stopped, and this was used as an excuse to take away the Muslims' rights. More efforts were made to force conversions. By 1501, it was officially said that no Muslims were left in Granada. Because this seemed successful, Queen Isabella of Castile made a law in 1502. This law banned Islam in all of Castile. When Spain took over Navarre in 1515, more Muslims there were also forced to become Christians.

The last part of Spain to force conversions was the Crown of Aragon. Its kings had promised to protect religious freedom for Muslims. But in the early 1520s, a Christian uprising called the Revolt of the Brotherhoods forced Muslims in rebel areas to convert. When the king's army, helped by Muslims, stopped the rebellion, King Charles I (also known as Charles V) decided that these forced conversions were still valid. This meant these "converts" were now officially Christians. They were then under the control of the Spanish Inquisition, a powerful church court.

In 1524, King Charles asked Pope Clement VII to let him break his promise to protect Muslims' religious freedom. The Pope agreed. So, in late 1525, King Charles issued a new law: Islam was no longer allowed anywhere in Spain.

Even though people had to act like Christians in public, many of the forcibly converted Muslims (called "Moriscos") secretly kept their Islamic faith. They couldn't follow traditional Islamic laws openly because of the Inquisition. So, a special religious opinion, called the Oran fatwa, was issued. It explained how Muslims could relax their religious rules to survive. This fatwa helped the Moriscos practice crypto-Islam (secret Islam) until they were expelled from Spain in 1609–1614. Some Muslims, especially near the coast, tried to leave Spain. But the authorities made it very hard to emigrate. Some rebellions also happened, especially in mountains, but they all failed. In the end, these laws created a society where secret Muslims lived alongside those who truly became Christians, until the final expulsion.

Why Did This Happen?

Islam in Spain's History

Islam had been in Spain since the 700s. By the early 1100s, about 5.5 million Muslims lived in Spain, which they called "Al-Andalus." These included Arabs, Berbers, and local people who converted. Over the next few centuries, Christian kingdoms from the north slowly took back land in a process called the reconquista. This caused the Muslim population to shrink.

By the late 1400s, the Reconquista ended with the fall of Granada. Granada was the last independent Muslim kingdom in Spain. At this time, about 500,000 to 600,000 Muslims lived in Spain. Most of them lived in the former kingdom of Granada, which was now part of Castile. About 20,000 Muslims lived in other parts of Castile, and many others lived in the Crown of Aragon. These Muslims living under Christian rule were known as the Mudéjars.

Promises of Freedom

After Granada was conquered in 1492, Muslims there and elsewhere were still allowed to practice their religion freely. This right was promised in many agreements, like the Treaty of Granada (1491). Kings of Aragon, including King Ferdinand II and Charles V, even swore an oath during their coronations to protect Muslims' religious freedom.

However, three months after Granada fell, in 1492, the Alhambra Decree ordered all Jews in Spain to convert or leave. This was the start of new, tougher policies. In 1497, Portugal, Spain's neighbor, also expelled its Jewish and Muslim populations. Unlike the Jews, Portuguese Muslims were allowed to move to Spain, and most did.

How Conversions Happened

In the late 1400s, Spain was mainly split into two kingdoms: the Crown of Castile and the smaller Crown of Aragon. When King Ferdinand II of Aragon married Queen Isabella I of Castile, it brought the two kingdoms together. Their grandson, Charles, later inherited both. Even though they were united, the two kingdoms had different laws and ways of treating Muslims. There were also Muslims in the Kingdom of Navarre, which Castile took over in 1515.

Forced conversions happened at different times in different places:

- Crown of Castile: 1500–1502

- Navarre: 1515–1516

- Crown of Aragon: 1523–1526

In the Crown of Castile

Granada's Conversions

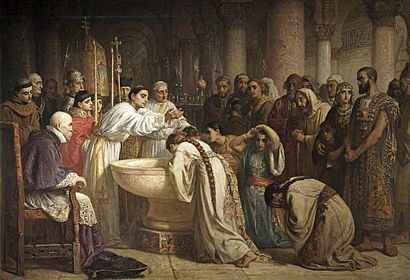

Cardinal Cisneros, a powerful church leader, started forcing conversions in Granada in 1499. Unlike the local archbishop, who was friendly with Muslims, Cisneros used harsh methods. He jailed Muslims, especially noblemen, and treated them badly until they converted. Cisneros ignored warnings that his actions might break the Treaty of Granada. He even wrote to the Pope that he converted 3,000 Muslims in one day.

These forced conversions led to a series of rebellions. The first started in Granada city. After the rebellion was stopped, Cisneros convinced King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella that the Muslims had lost their treaty rights by rebelling. The monarchs sent Cisneros back to Granada to continue the conversions. Many Muslims in the city were forced to convert. Cisneros claimed in January 1500 that "there is no one in the city who is not a Christian."

The uprising then spread to the countryside. People in the Alpujarra mountains rebelled, fearing they would also be forced to convert. But after several military campaigns in 1500–1501, the rebellion was defeated. The rebels had to accept baptism as part of their surrender. By 1501, no unconverted Muslims were officially left in Granada.

Conversions in the Rest of Castile

Muslims in other parts of Castile had lived under Christian rule for many generations. After the conversions in Granada, Queen Isabella decided to make a law for them: convert or leave. This law was announced in February 1502. It affected all Muslims in Castile and Leon. All Muslim males aged 14 or older, and females aged 12 or older, had to convert or leave Castile by the end of April 1502.

The law said that allowing Muslims to remain would be scandalous after Granada's conversions. It also claimed it was to protect new converts from the influence of non-converted Muslims. The law seemed to offer expulsion, but it made it almost impossible to leave. Muslims were forbidden from going to nearby regions like Aragon or Navarre. They couldn't go to North Africa or the Ottoman Empire. The only allowed destination was Egypt, but there were very few ships going there. They also had to leave from a port far north, which was very difficult for those in the south.

After the deadline, Islam became illegal. Those who helped Muslims who hadn't converted would be punished. A later law also stopped newly converted Muslims from leaving Castile for two years. With this law, the open practice of Islam in Castile ended.

Navarre's queen, Catherine of Navarre, and her husband did not want to force conversions. When the Spanish Inquisition tried to bother Muslims in Navarre, the royal court told them to stop.

However, in 1512, Castile and Aragon invaded Navarre. Spanish forces quickly took over the southern part of the kingdom. In 1515, Navarre officially became part of the Crown of Castile. This meant Castile's 1501–1502 conversion law now applied to Navarre. The Inquisition was put in charge of making sure it was followed.

Few Muslims in Navarre seemed to accept conversion. Many probably left Navarre to escape through Aragon to North Africa. Some stayed despite the order. For example, in 1520, 200 Muslims in Tudela were still listed as wealthy residents.

In the Crown of Aragon

Even though Ferdinand II oversaw conversions in Castile, he did not force them in his own lands of Aragon. Kings of Aragon had sworn an oath during their coronations to protect their Muslim subjects' religious freedom. Ferdinand repeated this oath in 1510 and kept his promise throughout his life.

Ferdinand died in 1516, and his grandson Charles V became king. Charles also swore the same oath. However, the first forced conversions in Aragon happened during the Revolt of the Brotherhoods. This rebellion, which was against Muslims, broke out in Valencia in the early 1520s. The rebels forced Muslims in their controlled areas to become Christians. Muslims actually helped the king's army fight against this rebellion.

After the rebellion was stopped, the Muslims thought these forced conversions were not valid. They went back to practicing Islam. But King Charles I (Charles V) started an investigation to decide if the conversions were valid. In 1524, Charles ruled that the conversions were valid. This put the forcibly converted Muslims under the Inquisition's power. Supporters of this decision argued that Muslims could have chosen to die rather than convert, so their conversion was "free."

At the same time, Charles tried to get out of his oath to protect Muslims. He asked Pope Clement VII to release him from it. The Pope at first said no, but in May 1524, he released Charles from his oath. The Pope also allowed the Inquisition to stop anyone who opposed the upcoming conversions.

On November 25, 1525, Charles issued a law ordering the remaining Muslims in Aragon to convert or leave. Like in Castile, leaving was almost impossible. To leave, a Muslim had to get papers from a town on Aragon's western border. Then, they had to travel across all of Castile to a port on the northwest coast. This had to be done by a strict deadline. Those who missed the deadline could be enslaved. Another law said that those who didn't leave by December 8 had to show proof of baptism. Muslims were also told to listen to Christian teachings without arguing.

A very small number of Muslims managed to escape to France and then to North Africa. Some rebelled against this order, like in the Serra d'Espadà. The king's troops defeated this rebellion, killing 5,000 Muslims. After these rebellions were crushed, all of Aragon was officially Christian. Mosques were destroyed, names were changed, and Islam was practiced only in secret.

What Happened Next?

Secret Islam

For those who couldn't leave, converting was the only way to survive. But most of these forced converts and their children (the "Moriscos") secretly continued to practice Islam. There is a lot of evidence, like their own writings and Inquisition records, that shows they kept their faith. Generations of Moriscos lived and died as secret Muslims.

However, they were pressured to act like Christians in public. They had to attend Christian church services or eat foods forbidden in Islam. This led to a new kind of Islam where inner belief (niyya) was more important than outward actions. Some Morisco writings describe how they used Christian worship to replace Islamic rituals. They also secretly prayed together and collected money for the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca), though it's not clear if anyone actually made the trip. They hoped to fully practice Islam again someday.

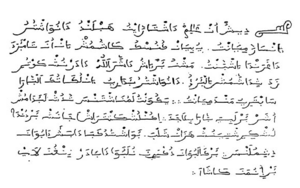

The Oran Fatwa

The Oran fatwa was an Islamic legal opinion issued in 1504. It was created to help Muslims deal with the forced conversions in Castile. It gave detailed ways for Muslims to relax Islamic laws. This allowed them to outwardly act like Christians when needed to survive. The fatwa gave easier rules for daily prayers, charity, and washing. It also told Muslims what to do when they had to break Islamic law, like worshiping as Christians or eating pork and wine. This fatwa was very important to the converted Muslims and their children. It became the main guide for secret Islam in Spain until the Moriscos were expelled.

Leaving Spain

Islamic scholars generally believed that Muslims should not stay in a country where they couldn't practice their religion properly. So, they said Muslims should leave if they could. Even before the forced conversions, religious leaders urged Muslims to emigrate to protect their faith.

However, Christian authorities usually tried to stop Muslims from leaving. So, emigration was only possible for the richest Muslims living near the southern coast, and even then, it was very hard. For example, in 1501, some Muslims in Granada were offered exile if they paid a high fee, which most couldn't afford. Some villagers tried to escape by sea with help from North Africa, but many were killed or lost everything.

Even when the law in Castile seemed to allow emigration, it banned almost all possible destinations. So, nearly all Muslims had to convert. In Aragon, Muslims who wanted to leave had to travel across all of Castile to a distant port, which was almost impossible to do in time. A small number did manage to escape to France and then to North Africa.

Fighting Back

Cardinal Cisneros's conversion campaign in Granada led to the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1499–1501). The king's forces won, and the defeated rebels were forced to convert.

After the conversion law in Aragon, Muslims also fought back, especially in the mountains. A rebellion started in Benaguasil. The king's first attack was pushed back, but the town surrendered after five weeks. The rebels were then baptized. A more serious rebellion happened in the Sierra de Espadan. The rebel leader called himself "Selim Almanzo," after a famous Muslim leader. The Muslims fought for months, pushing back several attacks. But the king's army, with 7,000 men including German soldiers, finally won on September 19, 1526. About 5,000 Muslims were killed, including old men and women. Some survivors escaped to North Africa, while others surrendered and were baptized.

True Conversions

Some converts truly became Christian. Cisneros said that some converts chose to die as martyrs rather than deny their new Christian faith when Muslim rebels demanded it. One convert named Pedro de Mercado refused to join the rebellion in Granada. In response, rebels burned his house and kidnapped his family. The king later paid him for his losses.

In 1502, the entire Muslim community of Teruel (in Aragon) converted to Christianity. This happened even though the 1502 law for Castilian Muslims did not apply to them. Some historians think they were pressured by nearby Castilians. Others believe they converted willingly after centuries of living with Christians and wanting equal status.

See also

In Spanish: Conversiones forzadas de musulmanes en España para niños

In Spanish: Conversiones forzadas de musulmanes en España para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |