Alhambra Decree facts for kids

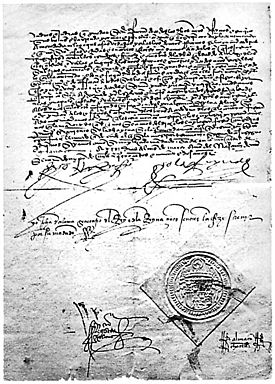

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion) was a special order given on March 31, 1492. It was issued by the rulers of Spain, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon. This order commanded all practicing Jewish people to leave the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. They had to leave by July 31 of that same year.

The main reason for this decree was to stop the influence of Jewish people on those who had recently converted to Christianity. Many Jewish people in Spain had converted to Christianity because of attacks and persecution. For example, over half of Spain's Jewish population converted after a big attack in 1391. By 1415, about 50,000 more had converted.

The rulers wanted to make sure these "New Christians" did not go back to practicing Judaism. Because of the decree, between 40,000 and 100,000 Jewish people chose to leave Spain. More than 200,000 others converted to Catholicism to stay. Some who left later converted to Catholicism to be allowed to return to Spain.

In 1924, a Spanish leader named Primo de Rivera offered Spanish citizenship to some Jewish people who had been expelled. The Alhambra Decree was officially cancelled on December 16, 1968. This happened after the Second Vatican Council, which was a big meeting of the Catholic Church. By then, Jewish people had been openly practicing their religion in Spain for a century. Synagogues were also legal places of worship again.

In 2015, Spain passed a law allowing Jewish descendants to get dual citizenship. This was to "make up for shameful events in the country's past." Jewish people who could prove they were descendants of those expelled in 1492 could become Spanish citizens. This law ended in 2019. However, descendants of Jewish people exiled from the Iberian Peninsula can still apply for Portuguese citizenship.

Contents

The Story Behind the Decree

Jewish Life in Early Spain

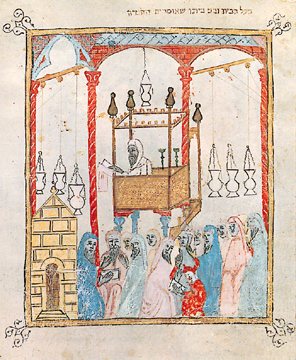

For a long time, Jewish people lived in the Iberian Peninsula (which is now Spain and Portugal). By the end of the 700s, Muslim forces had taken over most of this area. Under Muslim law, Jewish people were considered "People of the Book." This meant they had a protected status.

Before the Muslims, the Visigothic Kingdom had treated Jewish people very badly. They forced them to convert or become slaves. But the Muslim rulers of al-Andalus (Muslim Spain) were more tolerant. This allowed Jewish communities to grow and become successful.

Jewish merchants could trade freely across the Islamic world. This made Jewish communities in Muslim cities important centers for learning and business. Jewish scholars became doctors, diplomats, and poets in Muslim courts. They were not equal to Muslims, but they held important positions in some areas.

The Christian Reconquest

The Reconquista was a long period when Christian kingdoms in the North slowly took back Muslim Spain. This was driven by a strong religious goal: to reclaim Spain for Christianity. By the 1300s, most of the Iberian Peninsula was back under Christian control.

During the later parts of the Reconquista, Muslim kingdoms in Spain became less welcoming to Jewish people. In the late 1100s, a strict Muslim group called the Almohads took control. They gave Jewish people a harsh choice: leave, convert, or die. Many Jewish people fled to other Muslim lands or to Christian kingdoms.

At first, Christian kingdoms welcomed Jewish people. They worked as officials, merchants, and moneylenders. This made them useful to the rulers, who often protected them.

Growing Hostility and Conversions

As the Reconquista neared its end, hostility towards Jewish people in Christian Spain grew. There were many violent attacks. In the early 1300s, Christian kings allowed religious leaders to force Jewish people to listen to sermons. Later, angry mobs led by popular preachers attacked Jewish neighborhoods. They destroyed synagogues and forced Jewish people to choose between converting to Christianity or dying.

Thousands of Jewish people converted to Christianity to escape these attacks. These converts were called conversos or "New Christians." At first, many converso families became successful in society and business. But their success made them unpopular with their neighbors, including some church leaders and nobles.

By the mid-1400s, "Old Christians" demanded that the Church and monarchy treat them differently from conversos. This led to the first limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) laws. These laws limited opportunities for converts.

Suspicions and the Inquisition

Many Christians suspected that some conversions were not sincere. Some conversos secretly continued to practice Judaism. These people were called crypto-Jews. Families who had recently converted and kept marrying each other were especially watched. Jewish law said that conversions made under threat were not truly legitimate. The Catholic Church also officially opposed forced conversions. However, once someone was baptized, they were not allowed to go back to their old religion.

Expulsions in Europe

Spain was not the first country to expel Jewish people. From the 1200s to the 1500s, European countries expelled Jewish people at least fifteen times. Before Spain, Jewish people had been expelled from England in 1290 and several times from France. Usually, they were allowed to return after a few years. The Spanish expulsion was different because it was the largest and lasted the longest in Western Europe.

Early expulsions were often about money. Jewish communities were important for monarchs because they were a reliable source of taxes. Jewish people were also known as moneylenders. This was because Christians were not allowed to charge interest on loans. So, Jewish people often lent money to merchants, nobles, and even kings. Kings would sometimes tax Jewish communities heavily, then expel them, and take their remaining money and debts. The Spanish expulsion was different because its main reason was religious, not just financial.

Ferdinand and Isabella's Rule

Hostility towards Jewish people in Spain reached its peak during the rule of Ferdinand and Isabella. They were known as the "Catholic Monarchs." Their marriage in 1469 united the kingdoms of Aragon and Castile. This eventually led to the full unification of Spain.

At first, Ferdinand and Isabella protected Jewish people. But they heard reports that many Jewish converts were not truly Christian. Some conversos did secretly practice Judaism, but "Old" Christians often exaggerated how widespread this was. People also claimed that Jewish people were trying to bring conversos back to Judaism.

In 1478, Ferdinand and Isabella asked Rome to set up an Inquisition in Castile. This Inquisition's main job was to find and punish conversos who were secretly practicing Judaism.

These issues became very important during Ferdinand and Isabella's final conquest of Granada. Granada was the last Muslim kingdom in Spain. Jewish people and conversos helped a lot in this war by raising money and getting weapons. This increased Jewish influence made "Old Christians" and some religious leaders even angrier.

In 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella won the Battle of Granada. This completed the Catholic Reconquista of Spain from Muslim rule. However, the Jewish population became more hated by the people and less useful to the monarchs.

The Decree Itself

The king and queen issued the Alhambra Decree less than three months after Granada surrendered. Isabella was the main force behind the decision. The decree accused Jewish people of trying to "turn faithful Christians away from their beliefs."

After the decree was passed, all Jewish people in Spain had only four months to either convert to Christianity or leave the country. The edict promised them royal protection during this time. They were allowed to take their belongings, but not "gold or silver or minted money."

In reality, Jewish people had to sell everything they could not carry, like their land, houses, and books. It was hard to turn their wealth into something portable. The market was flooded with these goods, so prices dropped very low. This meant much of the Jewish community's wealth stayed in Spain. Any Jewish person who did not convert or leave by the deadline faced severe punishment, including being put to death.

Where Did They Go?

The Jewish people who left Spain, known as Sephardic Jews, went to four main areas: North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, and Italy.

- North Africa: Some Spanish Jewish people went to North Africa. However, in the 1490s, there was a severe famine there. Many cities in Morocco would not let the Spanish Jewish refugees in. This led to many refugees starving. Some were even captured and sold as slaves, though many of these sales were later cancelled. A number of Jewish people who fled to North Africa eventually returned to Spain and converted. Those who stayed in North Africa mixed with existing Jewish communities there.

- Ottoman Empire: Many Spanish Jewish people also fled to the Ottoman Empire. The Sultan, Bayezid II, sent his navy to bring them safely to Ottoman lands. Many settled in cities like Thessaloniki (in Greece) and İzmir (in Turkey). They also settled in other parts of the Balkans ruled by the Ottomans. Sultan Bayezid II reportedly said that Ferdinand and Isabella were foolish for sending him their "national treasure, the Jews."

- Portugal: Most Sephardic Jews went to Portugal. But they only had a few years of peace there. About 600 Jewish families were allowed to stay in Portugal after paying a large bribe. However, the Portuguese king wanted to marry Ferdinand and Isabella's daughter. To get this alliance, he declared all Jewish people in Portugal to be Christians by royal order, unless they left the country. He promised the Inquisition would not come to Portugal for 40 years. Then, he seized Jewish people who tried to leave and forced them to be baptized, even separating them from their children. Many years passed before Jewish people who fled to Portugal were allowed to leave. When they could, many went to the Netherlands.

Historians have different ideas about how many Jewish people were expelled from Spain. The number is likely less than 100,000, possibly as low as 40,000. This number does not include those who returned to Spain because they faced difficulties in other countries. Those who returned could recover their property if they converted. The Catholic monarchs wanted their subjects to be truly Catholic. They believed that persecuting converts would stop others from converting.

Conversions and Their Impact

Most of Spain's Jewish population had already converted to Christianity before the decree. About 200,000 people had converted due to earlier persecutions. The main goal of expelling practicing Jewish people was to make sure these many converts were sincere. Of the 100,000 Jewish people who remained Jewish in 1492, some chose to convert rather than leave.

New converts were closely watched by the Inquisition. The Inquisition was set up to find religious heretics. In Spain and Portugal, it focused on finding crypto-Jews. While Judaism itself was not heresy, pretending to be Christian while practicing Judaism was. Also, "purity of blood" laws created legal discrimination against descendants of converts. These laws prevented them from holding certain jobs or moving to the Americas. For years, people with urban backgrounds, trade connections, or who were educated and spoke many languages were suspected of having Jewish ancestry. People believed that someone with Jewish blood was untrustworthy.

These measures slowly faded as the identity of conversos was forgotten. This community eventually blended into Spain's main Catholic culture. This process lasted until the 1700s.

Spain's Modern Policy

The Spanish government has worked to make peace with the descendants of its expelled Jewish people. In 1924, the government offered Spanish citizenship to some Sephardic Jews. As mentioned, the Alhambra Decree was officially cancelled in 1968.

In 1992, on the 500th anniversary of the decree, King Juan Carlos prayed with Israeli president Chaim Herzog at a synagogue in Madrid. The King said that Spain is a place where Jewish people are truly at home. He emphasized looking to the future and learning from the past.

Since November 2012, Sephardic Jews have had the right to automatic Spanish nationality. They do not need to live in Spain first. Before this, they could get citizenship after living in Spain for only two years, instead of ten years for most foreigners. While their citizenship is being processed, they get protection from Spain's consulates. Spain is unique among European nations for offering automatic citizenship to descendants of Jews expelled during medieval times.

As of November 2015, 4,300 Sephardic Jews had gained Spanish citizenship under this law. In 2013, there were an estimated 40,000 to 50,000 Jewish people in Spain.

See also

In Spanish: Edicto de Granada para niños

In Spanish: Edicto de Granada para niños

- Edict of Expulsion

- Edict of Fontainebleau

- Expulsion of Jews from Spain

- Expulsions of the Jews from France

- Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain, a series of similar decrees affecting Muslims

- Expulsion of the Jews from Sicily

- Expulsion of the Moriscos

- Expulsions of Protestants from Salzburg

Images for kids

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |