Expulsion of Jews from Spain facts for kids

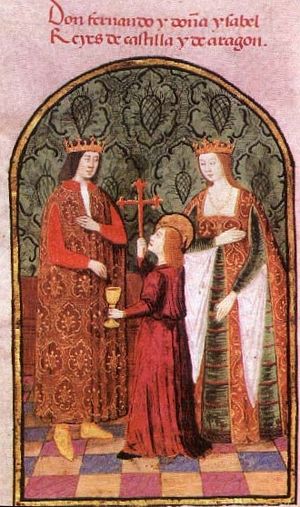

The Expulsion of Jews from Spain happened in 1492. This was when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella ordered all Jewish people to leave Spain. They did this with a special rule called the Alhambra Decree. The rulers wanted to make sure that people who had become Catholic (called conversos) would not go back to practicing Judaism.

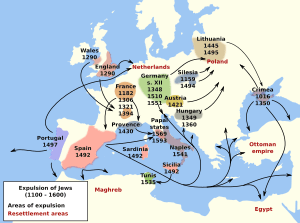

Many Jewish people in Spain had already become Catholic before 1492, especially after a big attack in 1391. More attacks followed, and by 1415, about 50,000 more had converted. Those who remained often chose to convert to avoid being forced to leave. In total, over 200,000 Jewish people became Catholic, while between 40,000 and 100,000 were expelled. Some later returned to Spain. This event caused many Jewish people to move to places like Italy, Greece, Turkey, and other parts of the Mediterranean Basin. You can even see this in some Jewish family names that started appearing in Italy and Greece, like Faraggi, which comes from the Spanish city of Fraga.

Much later, in 1924, the Spanish government allowed some Sephardic Jewish people (descendants of those expelled) to become Spanish citizens again. This order was officially removed in 1968. Then, in 2014, Spain passed a new law allowing descendants of the expelled Jewish people to get dual citizenship. This was meant to make up for past events. By 2015, the Spanish Parliament confirmed this law, giving descendants until October 1, 2019, to apply.

Why it Happened

Jewish People in Medieval Christian Spain

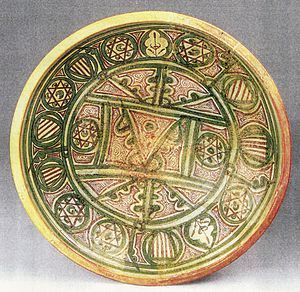

For a long time, Jewish people living under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus (parts of Spain) were generally accepted. They had fewer rights than Muslims but were often better off than Jewish people in Christian parts of Europe. However, some historians say that the idea of complete harmony between Jewish and Muslim people in Spain might be a bit of an overstatement.

On January 2, 1492, the Catholic Monarchs conquered the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, which was the last Muslim kingdom in Spain. This ended nearly 800 years of Muslim rule in Spain, a period known as the Reconquista.

In Christian kingdoms, Jewish and Muslim people were often treated poorly. They lived separately from Christians. In Muslim kingdoms, Christians and Jewish people had to pay a special tax to practice their religion.

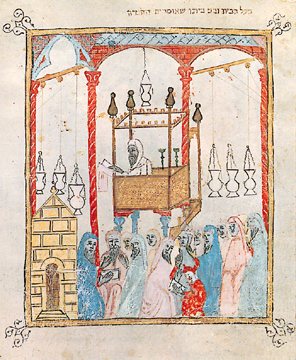

During the 1200s and 1300s, anti-Jewish feelings grew stronger in Christian Europe. This led to harsh rules against Jewish people, like those made at the Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215. Even though Spanish laws said Jewish people lived among Christians to remind them of those who "crucified Our Lord Jesus Christ," kings still protected them because they played important roles in their kingdoms.

However, in the 1300s, this period of relative tolerance ended. Things became more difficult for Jewish people. Wars, natural disasters, and the Black Plague created a new situation. People felt cursed and believed they were being punished for their sins. Religious leaders encouraged people to change their ways. At this time, the presence of Jewish people among Christians was seen as a problem.

The Violent Attacks of 1391

The first major wave of violence against Jewish people in Spain happened in 1321 in the Kingdom of Navarre. Later, the Black Death in 1348 caused attacks on Jewish neighborhoods in places like Barcelona. In the Crown of Castile, violence against Jewish people was linked to a civil war. One side, led by Henry II, used anti-Jewish ideas to gain support.

The biggest disaster for Jewish people in Spain happened in 1391. Jewish communities in Castile and the Crown of Aragon suffered terrible attacks. These attacks began in June in Seville, where a religious leader named Ferrand Martinez encouraged violence. Hundreds of Jewish people were killed, their homes were robbed, and their synagogues were turned into churches. Some Jewish people escaped, while others were forced to be baptized to save their lives.

From Seville, the violence spread across Andalusia and then to Castile. By August, it reached the Crown of Aragon. Many Jewish people were killed, their homes looted, and buildings burned. Those who survived either fled to places like Navarre, Portugal, France, or North Africa, or they chose to convert to Christianity. It's hard to know the exact number of victims, but hundreds were killed in cities like Barcelona, Valencia, and Lérida.

After these attacks, rules against Jewish people became even stricter. In Castile in 1412, Jewish men had to grow beards, and all Jewish people had to wear a special red badge on their clothes. In the Crown of Aragon, the Talmud (a Jewish religious text) was banned, and each Jewish community could only have one synagogue. Religious orders also pushed hard for Jewish people to convert. As a result of the 1391 attacks and these new rules, by 1415, more than half of the Jewish people in Castile and Aragon had converted to Christianity, including many important rabbis.

Jewish Life in the 1400s

After the terrible events of 1391-1415, only about 100,000 Jewish people continued to practice their religion in Castile and Aragon. Historians say that Spanish Judaism never fully recovered from this disaster. Jewish communities were smaller and deeply affected.

In the Crown of Aragon, Jewish communities almost disappeared in major cities like Barcelona and Valencia. Only the one in Zaragoza remained strong. In Castile, once-thriving communities in Seville, Toledo, and Burgos lost many members. By 1492, the year of the expulsion, the number of Jewish people in the Crown of Aragon was only a quarter of what it used to be. Many Jewish people had moved from big cities to smaller, rural areas, where they were safer from Christian attacks.

After 1415, the pressure on Jewish people eased a bit. They were able to get back some of their synagogues and books. They no longer had to wear the red ribbon or attend sermons by friars. They could also rebuild their community organizations and religious activities. This meant that the Crown of Castile officially recognized that some of its people had a different religion and allowed them to exist legally.

During the rule of the Catholic Monarchs (late 1400s), many Jewish people lived in villages and worked in farming. They also worked as craftspeople and traders, though international trade was mostly handled by converts. While some Jewish people still lent money, more Christians were doing this too. Jewish people also helped collect taxes for the king and church, but their role in this had become smaller. However, in the court of Castile, some Jewish people held important financial jobs. For example, Abraham Senior was a main treasurer for the Holy Brotherhood, which helped fund the war against Granada.

So, by the end of the 1400s, the Jewish community was not as rich or powerful as it once was. There were rich and poor Jewish people, just like in Christian society. What united them was their shared faith, which was different from the main religion. This made them a separate community, protected by the king.

Jewish communities had a lot of freedom to organize themselves. They chose their leaders, collected their own taxes to support their synagogues and religious schools, and followed Jewish law. They even had their own courts for civil cases. However, Jewish people did not have full civil rights. They paid higher taxes than Christians and could not hold positions of authority over Christians.

The situation of Jewish people raised a big question: could separate religious communities exist in a modern state that wanted to unite everyone under one authority? This was the real challenge.

Converts and the Inquisition

In the 1400s, a new problem arose: the conversos. These were Jewish people who had been baptized and their descendants. Many had been forced to convert, so "Old Christians" (those whose families had always been Christian) often didn't trust them.

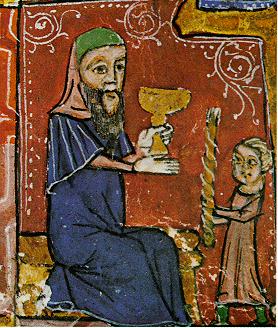

Converts often took over jobs that Jewish people used to do, like trade and crafts. Because they were now Christian, they could also enter professions that were previously forbidden to Jewish people. Some even became priests or bishops.

Old Christians often resented the converts' social and economic success. This resentment grew because converts often kept a distinct identity, proud of their Christian faith but also of their Jewish heritage. Between 1449 and 1474, there were popular uprisings against converts, especially during times of economic hardship. The first major revolt was in Toledo in 1449, where a rule was passed that banned anyone of Jewish background from holding city jobs. This was an early example of "blood-purity" laws. These revolts were often driven by economic problems, and leaders sometimes used the anger of the people to turn them against converts.

To justify attacks on converts, people claimed that conversos were not true Christians and secretly practiced Judaism. It's true that some who converted under pressure secretly returned to their old faith when they felt safe. These people were called "Judaizers." However, historians say that Judaizers were a minority. Some "proofs" of Judaizing were simply cultural habits, like resting on Saturday instead of Sunday, or not knowing Christian prayers well.

This led to the "converso problem." The Church believed that once baptized, a person could not give up their faith. So, secretly practicing Judaism was seen as a serious crime (heresy) that needed to be punished. This also led to the idea that the presence of Jewish people among Christians encouraged converts to continue practicing Jewish law.

When Isabella I of Castile became queen in 1474, she was married to Ferdinand II of Aragon. They decided to deal with the "converso problem." In 1475, a Dominican friar reported that many converts in Seville were secretly practicing Judaism.

After these reports, the monarchs asked Pope Sixtus IV for permission to appoint special judges called inquisitors in their kingdom. The Pope agreed in 1478. With the creation of the Tribunal of the Inquisition, the authorities had new ways to investigate and punish secret Jewish practices. King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella believed the Inquisition would force converts to fully become part of Christian society.

The Expulsion

Separating Jewish People (1480)

At the start of their rule, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella wanted to protect Jewish people because they were considered "property" of the crown. Many people even thought the monarchs were friendly towards Jewish people before 1492.

However, the monarchs couldn't stop all the unfair treatment Jewish people faced, often encouraged by religious preachers. To solve this, they decided to separate Jewish people from Christians. In 1476, the monarchs had already complained that old rules about Jewish people were not being followed (like not wearing fancy clothes, wearing a red badge, or holding positions of power over Christians). But in 1480, they went much further. They forced Jewish people to live in separate neighborhoods, called ghettos. They could only leave during the day for work.

Before 1480, Jewish neighborhoods were not completely separate; Christians lived in them too, and some Jewish people lived outside them. After 1480, these Jewish quarters became walled-off ghettos. This was done to prevent "confusion and damage to Christianity." The process was supposed to take two years but lasted over ten, and there were many problems and abuses by Christians.

This idea of confining Jewish people was not new; it had already happened in some Castilian towns. The goal was not just to separate them or protect them, but also to make their lives so difficult that they would choose to convert to Christianity. Their conversion was not directly demanded yet, but the conditions made it seem like the only way to live a normal life.

Expulsion from Andalusia (1483)

The first inquisitors arrived in Seville in November 1480 and immediately caused fear. In Seville alone, they sentenced 700 people to death and punished over 5,000 others with prison, exile, or other penalties. Their property was taken, and they were banned from public or church jobs.

During their investigations, the inquisitors found that many converts had been secretly meeting with their Jewish relatives to celebrate Jewish holidays and even go to synagogues. This convinced them that they couldn't stop secret Jewish practices if converts kept contact with Jewish people. So, they asked the monarchs to expel Jewish people from Andalusia. This request was approved, and in 1483, Jewish people in Seville, Cordoba, and Cadiz were given six months to leave for Extremadura. It's unclear if this order was fully carried out, as some reports say 8,000 Jewish families from Andalusia left from Cadiz and other ports in 1492.

Some historians believe the decision to expel Jewish people from Andalusia was also to move them away from the border with the Muslim Kingdom of Granada, where a war was happening.

The Expulsion Decree

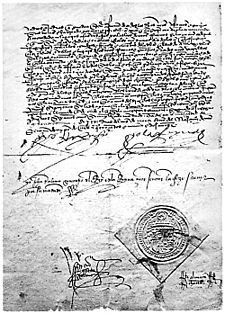

On March 31, 1492, shortly after the war in Granada ended, the Catholic Monarchs signed the decree to expel Jewish people in Granada. This decree was sent to all cities and towns, with orders not to make it public until May 1. Some important Jewish leaders tried to stop or soften the decree, but they failed. One of them, Isaac Abarbanel, offered King Ferdinand a lot of money. A famous story says that when the Grand Inquisitor Tomás de Torquemada found out, he threw a crucifix at the king's feet and said, "Judas sold our Lord for thirty pieces of silver; Your Majesty is about to sell him again for thirty thousand."

A few months before, an event in Avila helped create the right mood for the expulsion. Three converts and two Jewish people were executed by the Inquisition for supposedly harming a Christian child (known as the Child of La Guardia).

The Catholic Monarchs asked Tomás de Torquemada and his team to write the expulsion decree. They gave him three main conditions:

- The decree had to explain the expulsion by accusing Jewish people of two serious crimes: charging too much interest (usury) and encouraging converts to practice their old religion.

- Jewish people had to be given enough time to choose between baptism or leaving the country.

- Those who stayed true to their Jewish faith could sell their movable and immovable property, but they couldn't take gold, silver, or horses out of the country.

Torquemada presented the draft decree on March 20, 1492, and the monarchs signed and published it on March 31. This shows how important the Inquisition was in this decision.

There are two versions of the decree: one for the Crown of Castile, signed by both monarchs, and one for the Crown of Aragon, signed only by King Ferdinand. The Aragon version was harsher. It mentioned usury as a crime, said Jewish people were "ours" (meaning the king owned them), and used more insulting words, calling Judaism "leprosy" and saying Jewish people were "subject to perpetual servitude."

Despite these differences, both versions had the same main ideas. The first part explained why the monarchs decided to expel Jewish people, and the second part detailed how the expulsion would happen.

The Rules of Expulsion

The second part of the decree laid out the rules for the expulsion:

- The expulsion was permanent: "We agree to send out all male and female Jews from our kingdoms and [order] that none of them ever come back or return to them."

- There were no exceptions for anyone, no matter their age, where they lived, or where they were born.

- Jewish people had four months to leave, with an extra ten days, until August 10. If they didn't leave by then, or if they returned, they would be punished with death and lose all their property. Anyone who helped or hid Jewish people would also lose their property.

- Within these four months, Jewish people could sell their property and take the money as bills of exchange (like checks), not as coins or gold and silver, because exporting those was forbidden. They could also take merchandise, but not weapons or horses.

Although the decree didn't directly mention conversion, it was the unspoken alternative. As one historian said, Jewish people had "four months to make the most terrible decision of their lives: to abandon their faith to be integrated in it [the kingdom], or leave the territory in order to preserve it."

Most important Jewish leaders, except for a few like Isaac Abarbanel, chose to convert. The most notable case was Abraham Senior, the chief rabbi of Castile and a close helper of the monarchs. He and his family were baptized on June 15, 1492, with King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella as their godparents. This event was widely publicized to encourage others. Many Jewish people, especially the wealthy and educated, including most rabbis, were baptized during these four months.

Jewish people who decided not to convert faced terrible conditions. They had to sell their belongings quickly and often for very low prices, taking payment in goods they could carry, since gold and silver were forbidden to export. Taking bills of exchange was also difficult because bankers charged huge fees.

They also had trouble getting back money they had lent to Christians. Many debtors claimed the Jewish people had charged too much interest, knowing that the Jewish people wouldn't have time for courts to decide in their favor before they had to leave.

They also had to pay for all their travel expenses, like transport and ship fees. Isaac Abarbanel helped organize this, but ship owners sometimes charged very high prices or even robbed and killed travelers.

The monarchs had to issue orders to protect Jewish people during their journey because they faced harassment and abuse.

Reasons for the Expulsion

The Castilian version of the Alhambra Decree only mentioned religious reasons for the expulsion. The Aragon version also mentioned charging too much interest (usury). Jewish people were accused of encouraging converts to return to their old religion.

The monarchs and the Inquisition believed that Jewish people were causing new Christians to secretly practice Judaism. To stop this, the monarchs first ordered Jewish people to live in separate neighborhoods in 1480. Then, they expelled Jewish people from Andalusia, thinking this would be enough. But it didn't work, as Jewish people continued to "grow their evil and damaged purpose where they live."

Historians still debate the exact reasons for the expulsion. Some old ideas, like that Jewish people were expelled to take their wealth, are now mostly dismissed. Most of the Jewish people who left were not rich, and the wealthiest often converted and stayed. The crown also lost tax money from Jewish people. The idea that it was a class conflict (nobles against a rising middle class) also doesn't seem right, as many Jewish people were protected by powerful noble families.

A personal dislike from the monarchs can also be ruled out, as they had many trusted Jewish and convert advisors and doctors.

Today, historians often see the expulsion in a wider European context. Spain was actually one of the last major Western European countries to expel Jewish people (England did it in 1290, France in 1394, and many German and Italian cities in the 1400s). The goal for all these countries was to have one single religion in their states, following the idea that "the subjects should profess the same religion as their prince."

The expulsion ended a unique situation in Christian Europe where different religious communities lived together. Spain became like other European Christian nations. Many important thinkers of the time praised Spain for this decision.

Some historians believe the Catholic Monarchs were pressured by other Christian countries and the Church, which often preached against Jewish people. There was also strong anti-Jewish feeling among the Christian population. However, some historians disagree that the monarchs were simply trying to please the masses. The decree itself doesn't mention many of the common accusations against Jewish people, like ritual crimes.

For many historians, the decision was directly linked to the "converso problem." The Inquisition was created first, and then the expulsion of Jewish people was seen as a way to remove the supposed cause of converts secretly practicing Judaism. The monarchs wanted to completely unite converts into Spanish society. They hoped that the threat of expulsion would make many Jewish people convert, leading to a gradual blending. However, they were wrong. Most Jewish people chose to leave, enduring great hardship, to remain faithful to their religion.

What Happened Next

The End of Religious Diversity in Spain

In 1492, the open history of Jewish life in Spain ended. From then on, Jewish practices mostly went underground, always threatened by the Spanish Inquisition. Public opinion often saw Jewish people, secret Jewish practitioners, and even sincere converts as enemies of Catholicism and Spanish identity.

It's hard to know exactly how many Jewish people left Spain. Some early accounts exaggerated the numbers. Modern estimates suggest that out of about 400,000 Jewish people in Spain, about half (200,000 to 300,000) stayed as converts. Other estimates are lower, suggesting about 40,000 left and 50,000 converted. Those who left from Castile mostly went to Portugal (where they were later forced to convert in 1497) and North Africa. Those from Aragon went to other Christian areas like Italy, not just Muslim lands.

While most converts blended into Catholic culture, a small number continued to practice Judaism secretly. They gradually moved across Europe, North Africa, and the Ottoman Empire, often to places where other Sephardic communities already existed.

Those who returned to Spain after the expulsion had to be baptized, and their baptism had to be witnessed. They could also buy back their property for the same price they sold it. Returns are recorded until at least 1499. New rules also punished anyone who insulted these "New Christians."

The economic impact of the expulsion is also debated. It doesn't seem to have caused a major economic disaster for Spain or stopped the growth of capitalism. Most historians agree that Jewish people were no longer a main source of wealth for the country. The expulsion caused local problems but not a national catastrophe. Spain in the 1500s was not an economically backward nation.

A newspaper from Amsterdam, published in 1672, shows that Jewish communities abroad were still interested in what was happening in Madrid, even 180 years after the expulsion. This newspaper was printed in Spanish, showing how they kept their language. This document is kept at the Museum of the Jewish People in Tel Aviv, Israel.

The Sephardic Diaspora

Most of the expelled Jewish people settled in North Africa, sometimes after going through Portugal, or in nearby states like the Kingdom of Portugal or the Kingdom of Navarre, or in Italian states. Since they were also expelled from Portugal and Navarre later, they had to move again. Many from Navarre settled in Bayonne, and those from Portugal ended up in Northern Europe (England or Flanders). In North Africa, those who went to the Fez kingdom suffered greatly and were robbed. The ones who fared best settled in the Ottoman Empire, in North Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans, often after passing through Italy. The Ottoman Sultan welcomed them, and his successor, Suleiman the Magnificent, once said, referring to King Ferdinand, "You call him king who impoverishes his states to enrich mine?" He also commented to an ambassador that expelling Jewish people from Castile was like throwing away wealth.

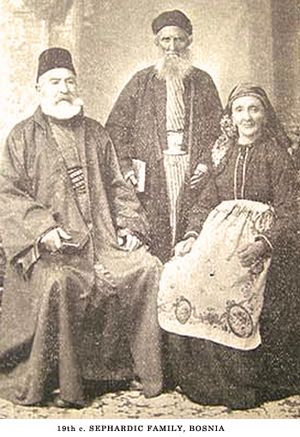

Because some Jewish people identified Spain and the Iberian Peninsula with the biblical land of Sepharad, the Jewish people expelled by the Catholic Monarchs became known as Sephardi. Besides their religion, they kept many of their old customs, especially the Spanish language. This language changed over time, but its basic structure remained that of medieval Castilian. The Sephardi people never forgot their homeland, feeling both sadness about the tragic events of 1492 and, over time, a longing for the home they lost.

See also

In Spanish: Expulsión de los judíos de España para niños

In Spanish: Expulsión de los judíos de España para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |