Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568–1571) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568–1571) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Principal centres of the Morisco Revolt |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

With the support of: Volunteers from the Kingdom of Fez |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Philip II Don John of Austria Marquis of Mondéjar Marquis of Los Vélez Duke of Sessa |

Abén Humeya †(1568-1569) Aben Aboo †(1569-1571) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,200 (initially) 20,000 (1570) |

4,000 (initially) 25,000 (1570) |

||||||

The Morisco Revolt (Arabic: ثورة البشرات الثانية; 1568–1571) was a big uprising in southern Spain. It is also known as the War of the Alpujarras. This conflict happened in the mountainous Alpujarra region, near the city of Granada.

The people who rebelled were called Moriscos. They were descendants of Muslims who had been forced to become Christians. Before this, they were known as Mudéjares, meaning Muslims living under Christian rule.

By 1250, Christian kingdoms had slowly taken back most of Spain from Muslim rule. This process was called the Reconquista. The last Muslim kingdom was the Emirate of Granada. In 1491, the city of Granada fell to the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon. At first, the Muslims were allowed to keep their religion.

But soon, in 1499, the Muslim people in Granada revolted against Christian rule. This first revolt was quickly stopped. After that, Muslims were told they had to become Christians or leave Spain. Most chose to convert and were then called "Moriscos."

However, many Moriscos secretly kept their old customs and language. This led to a lot of unhappiness. In December 1568, a Morisco leader named Aben Humeya started a second rebellion. This violent war lasted until March 1571. It mainly took place in the Alpujarra mountains, south of the Sierra Nevada.

During the revolt, there were rumors that the Ottoman Empire would help the Moriscos. This made many Moriscos believe their Christian rule was ending. They attacked priests and destroyed churches. After the revolt, most Moriscos were forced to leave Granada. They were sent to other parts of Spain. To fill the empty villages, Catholic settlers were brought in from other areas.

Contents

Why the Rebellion Started

Granada's Fall and Earlier Revolts

The Kingdom of Granada was the last Muslim-ruled state in Spain. After a long fight, the city of Granada was taken by the Catholic Monarchs in 1492. The first agreement, the Treaty of Granada, allowed Muslims to keep their homes and laws. They were not forced to change their religion.

But soon, there was pressure to convert. This led to an uprising in Granada city in 1499. More serious revolts followed in the mountain villages of the Alpujarra in 1500. King Ferdinand himself led an army to stop these revolts. The Catholic forces were very harsh. In one event in Laujar de Andarax, 200 Muslims were burned in a mosque.

Because of these revolts, the Catholics said the Muslims had broken the Treaty of Granada. So, the treaty was cancelled. Muslims in the region now had to choose: become Christian or leave Spain. Most chose to convert. They became known as "Moriscos" or "New Christians." But many still spoke Arabic and kept their old customs.

Reasons for the Second Uprising

In 1526, Charles V (who was also King Charles I of Spain) made a new law. This law said that rules against "heresy" (like Muslim practices by "New Christians") would be strictly enforced. It banned speaking Arabic and wearing traditional Moorish clothes. The Moriscos paid a large sum of money (80,000 ducados) to delay this law for 40 years.

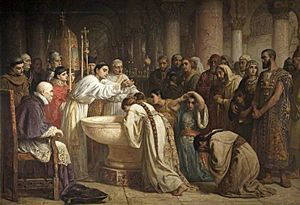

Since all Moors were now officially Christians, mosques were destroyed or turned into churches. However, there was little effort to teach them about Christianity. Priests themselves often didn't know enough to explain it. Instead, Moriscos were punished if they missed Sunday Mass. They had to learn Christian prayers in Latin. Children had to be baptized, and marriages had to follow Christian rules. This caused a lot of tension.

In 1565, the archbishop of Granada believed that Moriscos were not truly Christian. He called a meeting of bishops. They decided to use force instead of persuasion. The rules from 1526 would now be put into action. This meant banning all Morisco practices: their language, clothes, public baths, and religious ceremonies. Also, "Old Christians" (people who were always Christian) were to live in Morisco villages. Morisco homes were to be checked on certain days to make sure they weren't practicing Muslim rites. Children were to be sent away to Old Castile to learn Christian ways.

King Philip II, who became king in 1556, approved these strict rules. This led to the Pragmatica law on January 1, 1567. The Moriscos tried to get the law stopped, like they did in 1526. But King Philip was firm. A Morisco leader, Francisco Núñez Muley, protested. He said, "Day by day our situation worsens, we are treated badly in every way." He asked why they couldn't use their own language, like Christians in other countries who spoke Arabic.

When their pleas failed, the Moriscos of Granada began to plan a rebellion. They held secret meetings. The authorities arrested Moriscos they thought were plotting. They also planned to expel Moriscos and replace them with "Old Christians." After a year of failed talks, in 1568, the Morisco leaders decided to fight.

The Rebellion (1568–1571)

After the Pragmatica law was announced in January 1567, the Moriscos prepared for their revolt. They hid weapons, food, and other supplies in hard-to-reach caves. These supplies were enough to last for six years.

The main leaders met in secret houses in the Albaicín, the Moorish quarter of Granada. From there, they gave their orders.

On September 17, 1568, they decided to choose a leader for the revolt. The rebellion began on Christmas Eve in the village of Béznar. Hernando de Córdoba y Valór was named King. In a special ceremony, he was dressed in purple, like the old kings of Granada. Many rich Moriscos attended. He was chosen because he came from the Omeya family, who were caliphs of Córdoba. He took the Moorish name Abén Humeya. Many other Morisco villages in the Alpujarra joined the revolt.

The first action was in Granada city. Aben Humeya's "grand vizier," Farax Aben Farax, led a group of outlaws into the Albaicín on December 24-25. He wanted the Moriscos there to join the revolt. But few followed him. This failure in the capital greatly affected the whole rebellion.

The rebellion became very violent. Priests and church workers were attacked and killed. Churches were destroyed and disrespected. Groups of outlaws played a big part in this violence.

First Stage

The Spanish campaign was led by the Marqués de Mondéjar in the west and the Marqués de Los Vélez in the east. Mondéjar, coming from Granada in January 1569, had quick success. He crossed a damaged bridge at Tablate and reached Órgiva. There, he rescued Christians held captive.

The first big battle was in a river valley east of Órgiva, where the Moors were defeated. A small group of soldiers crossed a narrow valley and climbed a steep mountain. They reached Bubión, in the Poqueira valley. Aben Humeya had his headquarters there, and the Moors had stored supplies. The Marqués and his main army soon joined them.

In the next few days, the army crossed the mountains. They went to Pórtugos and Pitres, freeing more Christian captives. From there, they could reach villages further east.

Historian Henry Charles Lea described Mondéjar's "short but brilliant campaign." He said Mondéjar fought many battles through snow and cold mountains. The Moriscos quickly lost hope and tried to surrender. By mid-February 1569, the rebellion was almost stopped. Aben Humeya was hiding in caves.

At Pórtugos, some Moorish leaders tried to talk about surrender with Mondéjar. He said he would speak to King Philip for them. But he also said that rebels would still be punished. Mondéjar was later criticized for being too kind. The Christian campaign was also hurt by a long-standing rivalry between the two commanders.

The soldiers committed many cruel acts. This was not a trained army. It was mostly volunteers who were not paid. They expected to get rich from stealing. One writer said half of them were "the worst scoundrels in the world." They only wanted to steal, loot, and destroy Morisco villages.

Moriscos also took revenge on "Old Christians." Some priests were killed in cruel ways. Churches were systematically burned and looted. The homes of priests and other Christians were also destroyed.

Both sides sold their captives as slaves. Moriscos sold Christians to traders from North Africa for weapons. Christian soldiers took Morisco captives, especially women, as war prizes. They kept the money from selling them. Even the King benefited from selling slaves, like the Moors from Juviles who were sold in Granada.

Second Stage

This stage lasted from March 1569 to January 1570. Now, the Morisco rebels took the lead. More towns joined the revolt. Their numbers grew from 4,000 in 1569 to 25,000 in 1570. This included some Berbers and Turks who came to help. The rebels used ambushes, avoiding open battles. They used their knowledge of the mountains to launch surprise attacks.

The Spanish navy was called to bring more soldiers. It also protected the coast of Granada from Ottoman ships coming from North Africa.

Third Stage

This stage began in 1570. King Philip removed the Marqués of Mondéjar from command. He appointed his half-brother, Don John of Austria, to lead the army. The Marquis of Los Vélez continued fighting in the eastern part of the kingdom.

Lea described Vélez as "ambitious, arrogant and opinionated." He said Vélez made mistakes but was a favorite of the king. Big preparations were made to give Don John a strong army. Towns were ordered to provide soldiers. The Spanish ambassador in Rome was told to bring Italian ships to Spain. These ships would guard the coast and stop help from Africa. They would also bring a large group of regular troops from Naples.

This was a huge effort to deal with a revolt by mountain people. The rebels had no military training or good weapons. But King Philip was worried about problems in other countries. He wanted to solve this problem at home quickly. An Ottoman fleet had attacked Spanish coasts. In the Spanish Netherlands, there were riots and war. Philip did not want trouble in Spain. Also, like other Catholic leaders, he wanted to stop "heresy." The Moors were now officially seen as heretics.

Don John arrived in Granada in April 1569. There were many disagreements, and nothing was done for a while. The campaign fell apart. The Moriscos who had surrendered lost hope. They rejoined the rebellion. Granada was almost under siege. The rebels attacked the plain right up to the city gates. The rebellion spread to other mountain areas. It seemed like Spain's power might not be enough to stop it.

In an attack on Albuñuelas, Spanish troops killed all the men who didn't escape. They took 1,500 women and children as slaves. In October that year, the king declared "a war of fire and blood." This meant it was no longer just about stopping a rebellion. He also let soldiers take whatever they wanted, like slaves, animals, or property.

In January 1570, Don John started his new campaign with 12,000 men. Another army, led by the Duke of Sessa, had 8,000 foot soldiers and 350 horsemen. There was more fighting in the Pitres-Poqueira area in April 1570. As the campaign continued, many Catholic soldiers left the army.

On February 10, after a two-month siege, Don John captured Galera and ordered it destroyed. In March, he took Serón. At the end of April, he went to the Alpujarra, setting up his base at Padules. There, he met the Duke of Sessa's army. This army had left Granada in February and crossed the Alpujarra from west to east. At the same time, a third army came from Antequera to the sierra of Bentomiz, another rebel area.

Fourth Stage

This stage lasted from April 1570 until spring 1571. Catholic forces were greatly strengthened with more soldiers and cavalry. Led by Don John and the Duke of Sessa, they launched a new campaign. They invaded the Alpujarra, destroying homes and crops. They killed men and took all women, children, and old people as prisoners. Spain had used all its strength to raise a huge army.

In May, King Aben Aboo finally agreed to surrender. Those who gave up and handed over their weapons would be spared. But then, some Berbers arrived with news of more help coming. Aben Aboo decided to keep fighting. The reports are unclear. Some say three ships from Algiers with weapons turned back because they heard Aboo was surrendering. No help reached the rebels. But this gave the Catholics an excuse to restart the fighting. In September 1570, the mountains were attacked from both sides. It was a war of total destruction. They destroyed all harvests, killed men, and took thousands of women and children as slaves. Few prisoners were taken; those who were, were executed or sent to work on ships.

This advance by the royal troops caused a split among the Moriscos. Some wanted to keep fighting, while others wanted to surrender. In May, after a meeting, many rebels fled to North Africa. Soon after, Aben Aboo ordered the execution of Hernando El Habaqui, who wanted to surrender.

Even though many Moriscos surrendered from October 1570, several thousand kept fighting. Most hid in caves. But many died when Christian troops lit fires at the entrances, suffocating them.

In 1571, John of Austria finally stopped the rebellion in the Alpujarra. The last rebels were killed in their caves, including Aben Aboo. Resistance then ended.

Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, a Spanish writer of the time, wrote sadly about the war. He said they fought a strong enemy in difficult terrain. Finally, the rebels were driven from their homes. Men and women were chained together. Captured children were sold as slaves. He called it a "dubious victory," meaning it was not a clear win, because of its terrible results.

How Big Was the Rebellion?

When the rebellion began, the Kingdom of Granada had about 150,000 people. Most of them were Moriscos. We don't know the exact number of rebels. But ambassadors from France and Genoa said there were 4,000 rebels in January 1569. By spring 1570, there were 25,000. About 4,000 of these were Turks or Berbers from North Africa who came to help.

On the other side, the royal army started with 2,000 foot soldiers and 200 cavalry under the Marqués de Mondéjar. The number grew a lot when Don John took charge. In the siege of Galera, he had 12,000 men. The Duke of Sessa had between 8,000 and 10,000 men at the same time.

The rebellion started in the Alpujarra. But it spread to the plains and other mountain areas around the Kingdom. A very dramatic fight happened on a ridge above Frigiliana. Whole families of Moriscos had gathered there. The siege lasted from June to September 1569. Spanish reinforcements came by sea to help. Moriscos living in big towns like Almería, Málaga, Guadix, Baza, and Motril did not join the uprising. But they did feel sympathy for the rebels.

The towns had a different attitude because there were more "Old Christians" there. Also, the Moriscos in towns were better mixed into the communities. In the Alpujarra and other rebel areas, some villages had only one "Old Christian," who was the priest.

After the Rebellion: Moving People Around

After the revolt was stopped, many Moriscos were forced to leave the former Kingdom of Granada. First, they were gathered in churches. Then, in harsh winter conditions with little food, they were marched in groups, guarded by soldiers. Many died along the way. Some went to Cordova, others to Toledo, and even as far as Leon. Those from the Almería region were taken by ship to Seville. About 80,000 Moriscos were expelled. This was about half of Granada's Morisco population.

These forced moves caused a big drop in the population. It took decades for the numbers to recover. It also hurt the economy badly, as Moriscos were a main part of it. Many fields were left unplanted, and farms and workshops were destroyed during the fighting.

The Spanish government started planning to repopulate the land in 1571. The land left empty by the Moriscos would be given to new settlers. These settlers would get support until their land produced crops. Shared land would stay shared. Irrigation channels (acequias) and water reservoirs would be fixed. Springs would be for everyone. Pastures would be for livestock. They were also promised tax benefits. Settlers received bread, flour, seeds, clothes, tools, and animals like oxen and horses.

Officials from Granada looked for new settlers from far away, like Galicia and Asturias. This process was hard, slow, and costly. Most settlers came from western Andalucía. But some also came from Galicia, Castile, Valencia, and Murcia.

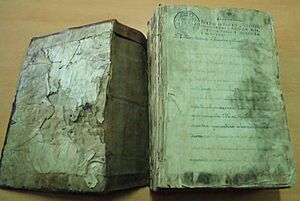

A property record book, the Libro de Apeos, for the Poqueira valley villages gives a lot of information. It shows that there were 23 settlers in Bubión, 29 in Capileira, and 13 in Pampaneira. In Bubión, nine came from Galicia. Five were already living in the village, including three widows and two church members. The book lists all the names, and some are still found today.

Land started to be given out in September 1571. Most settlers received specific amounts of irrigated land, vineyards, silkworm eggs, and fruit trees. Grain and olive mills remained public property for six years. These grants were officially announced in Bubión on June 28, 1573. Then, the settlers could start working on their new lands.

Life was not easy for them. Houses were in bad shape. Irrigation channels were damaged. Most livestock had disappeared. Many settlers had no experience farming in the mountains. Many gave up. By 1574, only 59 families were left in the Poqueira valley out of the original 70.

The resettlement program never brought the Alpujarra population back to its old numbers. Before the Reconquista, the Alpujarra probably had about 40,000 people, mostly Moors. The war of 1568–71 and the expulsions left only a few hundred Morisco families. Only seven were left in the Poqueira valley.

About 7,000 Christian settlers actually stayed in the Alpujarra. Many were single or had small families. Moorish families usually had five or six people. So, before the rebellion, the population was around 40,000. Slowly, the settler families grew. The population reached 12,000 by 1591. But then, there was a plague, locusts from Africa, and years of drought. The population dropped sharply and recovered slowly.

Some villages were abandoned. In the Poqueira, the small village of Alguástar was empty by the end of the 1500s, likely due to the plague. Generally, the settlers kept the houses as they were. When they built new ones, they copied the flat-roof style. Mosques were destroyed or became churches. Towers replaced minarets.

Between 1609 and 1614, the Spanish Crown expelled Moriscos from all over Spain. About half of Granada's Moriscos stayed in the region after the first dispersal. Only 2,000 were expelled from Granada city. Many stayed mixed with and protected by "Old Christians" who were less hostile to them than in other parts of Spain.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Rebelión de las Alpujarras para niños

In Spanish: Rebelión de las Alpujarras para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |