Alabama Creole people facts for kids

The flag of Mobile, Alabama.

|

|

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Alabama | |

| Languages | |

| English, French, Creole French, Mobilian Jargon | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholic (traditional), Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Louisiana Creoles, Isleños, Cajuns, Creoles of color, Acadians, Québecois, Creek Indians, African Americans |

Alabama Creoles (French: Créoles de l'Alabama) are a special group of people from the area around Mobile, Alabama. They are descendants of early French and Spanish settlers who came to Mobile in the 1700s.

Sometimes, they are called Cajans or Cajuns (French: Cadjins). However, they are different from the Cajuns in southern Louisiana. Most Alabama Creoles do not come from the French settlers of Acadia.

Contents

Who Are the Alabama Creoles?

In 1702, explorers led by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville moved from Biloxi. They settled on the west bank of the Mobile River. Here, they started a new outpost called Mobile. They named it after the local Maubilian Indians.

French soldiers, Canadian fur traders, and a few merchants lived in Mobile. They traded furs with Native Americans, which was very important for their economy. Some settlers also raised cattle and made wood products for ships.

Early Life in Mobile

Native American groups visited Mobile every year. The French would welcome them with food, drinks, and gifts. About 2,000 Native Americans would stay for up to two weeks.

Because the French and Native Americans were friendly, they learned from each other. French colonists learned the local Native American language, called Mobilian Jargon. Many French settlers also married Native American women.

Mobile was a mix of many different people. There were French people from Europe, French-Canadians, and various Native American groups. They all lived and worked together.

Slavery and the Code Noir

In 1721, the French also brought enslaved people to Mobile. Many of these enslaved people came from the French West Indies. They brought parts of African and Caribbean French Creole culture to Mobile.

In 1724, a set of rules called the Code Noir was started. This code gave enslaved people some legal and religious rights. These rights were not found in British or American colonies. The Code Noir also said that affranchis (ex-slaves) had full citizenship. This meant they had the same rights as other French people.

By the mid-1700s, Mobile was a diverse town. It had West Indian French Creoles, European Frenchmen, French-Canadians, Africans, and Native Americans. They were all united by the Roman Catholic religion. The town had about 50 soldiers and 400 civilians. This group included merchants, workers, fur traders, craftspeople, and enslaved people. This mixed group and their children became known as Creoles.

British Rule in Mobile

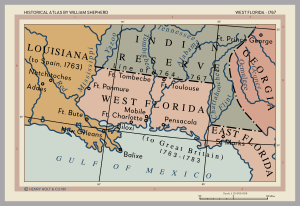

In 1763, France lost its lands in North America after the French and Indian War. Britain took over the southern parts of Louisiana, including Mobile. Some Creoles from New Orleans moved to Mobile because they preferred British rule.

Life for Alabama Creoles did not change much under British rule. The fur trade continued, and the British kept the Creole custom of holding meetings with Native American groups.

However, the British made stricter rules for enslaved people. It became harder for enslaved people to gain their freedom. Enslaved people also became very expensive. To get more workers, white indentured servants were brought in. These servants usually worked for a few years, and their masters provided them with housing, food, and clothing.

Spanish Rule and American Takeover

In 1783, Spain took control of British East and West Florida after the American Revolutionary War. Fur trading remained very important in Mobile. Mobile still had a diverse population, and Spain wanted more people to settle in its Florida colonies.

Spain offered very open policies to attract British and American settlers. While other Spanish colonies required everyone to be Catholic, people in Florida could worship as they pleased. The government also gave away land to new settlers. By 1788, Mobile's population grew to over 1,400 people.

Mobile Becomes American

Over time, Americans wanted the Spanish lands. In 1803, the United States bought French Louisiana from Napoleon Bonaparte. Americans claimed that the Spanish Floridas were part of this purchase. Americans living in Florida began to plot against the Spanish government.

During the War of 1812, Americans finally had a reason to take Spanish Mobile. On April 11, 1813, American forces easily defeated the Spanish troops in Mobile. Two days later, the Spanish commander surrendered Fort Charlotte.

In 1815, Americans won the Battle of New Orleans against the British. This victory showed that the United States was determined to keep the land it had won. From then on, Mobile was an American city.

Mobile as an American City

After the War of 1812, the first Americans to arrive in Mobile were merchants. They saw a great chance for business, especially compared to New Orleans, which was not yet a big trading center. As Mobile grew, doctors, lawyers, and printers also moved there.

Mobile grew quickly because cotton from nearby farms flowed through its ports. Mobile became a rich and refined city. It was the third most important port city in the United States, after New York City and New Orleans.

Mobile earned the nickname "Athens of the South" because it was so rich and successful. Many European immigrants came to Mobile. By 1860, Mobile had a population of 30,000 people.

In 1844, a visitor described Mobile's diverse and beautiful population:

"...clerks of all shapes and sizes, white and red haired men... Here goes a staid, demeure-faced priest and behind him is a dashing gambler... Here is a sailor just on shore... and there is a beggar in rags. Pretty Creoles, pale-faced sewing girls, painted vice, big-headed and little-headed men... a great country this is and make no mistake."

Mobile's Creole Community

Mobile had about 40% of all the free black people in Alabama. Many of Mobile's free people of color were Creoles. These Creoles came from many different backgrounds. They formed an important group with their own schools, churches, and social clubs.

Many Creoles were descendants of free black people when Americans took Mobile. They kept their freedom and were treated as a unique group by the American government. Other Creoles were related to white Mobilians, including important families.

Fun and Culture in Mobile

People from all parts of Mobile society enjoyed having fun. For the rich, life was full of balls, parties, and parades. Mobile had many private social clubs and groups that hosted dances. A popular ball was held on January 8th to remember the Battle of New Orleans.

Everyone in Mobile, no matter their background, enjoyed horse races. People could bet on their favorite horses. Cockfighting also became popular in the 1840s and 1850s.

Like New Orleans, Mobile was proud of its lively theater scene. Black people attended Mobile's theaters. People in Mobile watched plays by Shakespeare, comedies, and funny shows.

Mardi Gras became very important. Special groups called mystic societies started putting on masked parades. These parades had bands, floats, and horses. After the parades, members would go to grand balls. The floats often showed scenes from ancient times. In 1841, one group's floats of Greek gods were called "one of the most gorgeous and unique spectacles."

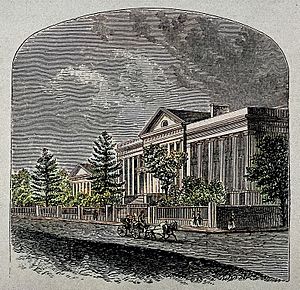

The Catholic community, mostly of French Creole descent, was large and important. In 1825, they began building the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. It took 15 years to build. For most of this time, Catholics and Protestants got along well.

The Creoles of Mobile built their own Catholic school for Creole children. People in Mobile supported many literary groups, bookstores, and music publishers.

Alabama Creoles Before the Civil War

Before the American Civil War, Mobile was a unique mix of cultures. It had black people (both enslaved and free), Native Americans, white people, and people of mixed races. There were also immigrants from every major European country. Catholics, Jews, and Protestants of different types all lived together.

The system of slavery caused problems for white Alabamians. Many white Southerners said slavery was good for enslaved people. However, the large Creole community in Mobile made this argument difficult. How could slavery be good for everyone when the Creole population was not only free but also doing well?

Creoles had their own schools, churches, and social groups. Enslaved people in the city could earn money and spend time with other enslaved people and free black people. Following an old Creole custom, many enslaved people hired themselves out and saved money. Enslaved people in Mobile learned to read and write from the educated Creoles. They often gained freedom through their skilled work.

The time before the Civil War was very lively in Mobile. But it did not last long. Young Alabama Creoles who started their lives in the 1820s saw their city and their achievements destroyed by the American Civil War. They, more than other Alabamians, tried to avoid this war.

Alabama Creoles During the Civil War

During the Civil War, Creoles in both Louisiana and Alabama asked the Confederate government to let them form military units. They wanted to protect their homes and cities. In New Orleans, Creoles formed the Louisiana Native Guard in 1861. However, Confederate forces later disbanded this unit.

Creoles in Mobile also kept asking to join the war effort. In November 1862, Alabama's government passed a law allowing Creoles to join the state militia. A unit called the Alabama Creole Guards was formed.

In November 1863, General Dabney H. Maury asked the Confederate War Department to accept the Creole militia into Confederate service. He wanted them to operate Mobile's shore cannons. But Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon said no. He stated that black people could never be Confederate soldiers.

However, in 1864, Mobile needed more defenders. Creoles joined Confederate cavalry units. A company of Creoles, called the Native Guards, formed from a Creole firefighting group. After the Union forces defeated the Confederates in Mobile, the Creole Native Guards disappeared from service.

Mobile After the Civil War

The Civil War completely changed Mobile. Before the war, Mobile was Alabama's most important city for business and social life. After the war, Mobile's economy struggled, and its population went down. Birmingham grew and became Alabama's largest city instead.

For Creoles in Mobile, the time after the war was difficult. Poor economic conditions lasted until World War I. Also, a rise in racism took away many rights that Creoles once had. A strict system of racial separation took hold in Mobile. Everyone was classified as either black or white. This informal but strict segregation limited the social and economic activities of Creoles.

In 1901, racist laws were passed to stop black people in Mobile from voting. The Creoles of Mobile pleaded with the state's white leaders, but it did not help. Many Creoles looked to their past for comfort. They continued to have their own schools, churches, social clubs, and the famous Creole Steam Fire Company Number I.

Creoles worked as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and business people. They copied the customs of Mobile's white elite. They formed their own mystic societies and created a "Colored Mardi Gras" celebration.

By the end of the 1930s, Mobile was a small town. Most people were happy with their community. However, the city was deeply divided by race. The lack of economic chances held back the city's growth. Mobile's Creole population was prevented from fully helping to build a better city.

Alabama Cajans

- Further information: Cajuns

Country Creoles who lived outside Mobile, in the forests of Baldwin County, and the hills of Mount Vernon, were called Cajans after the Civil War. Their name came from a changed version of "Acadian," like the Cajuns of Louisiana.

Creoles at this time used "Cajun/Cajan" (French: Cadjin) to mean a "Creole peasant." The Cajans of Alabama used this name to show they were different from the city Creoles of Mobile.

Alabama Cajans had different racial backgrounds. Under Alabama's new racial laws, some were seen as black, some as white, and some as Native American. Cajans faced discrimination because of their mixed race. Many could not read or write because they did not have access to public schools. Cajans tended to stay within their own communities.

Alabama Creoles After World War II

World War II changed Mobile's economy. New industries appeared, and Mobile became an important port again. After World War II, racial tensions grew. This led to the protests and riots of the Civil Rights Movement. This movement changed the situation for black people in the United States. After the Civil Rights Movement, official segregation, discrimination, and not being allowed to vote were finally ended.

The Creoles of Alabama slowly became less distinct. Some moved to other states. Others joined a broader black culture that focused on roots in slavery and black unity. In this process, they sometimes lost their Creole history, language, and heritage.

The last people who spoke Alabama Creole French died on Mon Louis Island in the 1990s.

Images for kids