Old Mobile Site facts for kids

Quick facts for kids |

|

|

Old Mobile Site; Fort Louis De La Louisiane

|

|

|

|

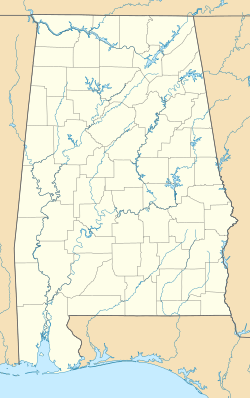

| Location | Mobile County, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Le Moyne, Alabama |

| Area | 117 acres (47 ha) |

| Built | 1702 |

| NRHP reference No. | 76000344 |

| Added to NRHP | May 6, 1976 |

The Old Mobile Site was where the French built their first main settlement, called La Mobile, and a fort, Fort Louis de La Louisiane. This happened in the French colony of New France in North America, from 1702 to 1712.

The site is in Le Moyne, Alabama. It's located on the Mobile River in the Mobile–Tensaw River Delta. For a while, from 1702 to 1711, this settlement was the capital city of French Louisiana. Then, the capital moved to where Mobile, Alabama is today.

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville founded and first led the settlement. After he passed away, his younger brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, took over. You can think of Old Mobile as the French version of the English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia.

The Old Mobile Site and its fort were added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 6, 1976. It was also recognized as a National Historic Landmark on January 3, 2001.

Contents

History of Old Mobile

Why Mobile Was Founded

After Spain's power started to fade around 1588, France became more important in Europe. At the same time, England was getting more involved in the New World (the Americas). Under King Louis XIV, France built a strong army and navy. This allowed them to explore and settle places like Canada. By 1608, the French flag was flying over Quebec.

Jesuit missionaries traveled to teach Indians about their religion. Explorers like Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi River. Later, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle traveled down the river in 1682. He claimed the entire Mississippi basin for France.

France soon realized they needed a fort on the Gulf of Mexico. This would help them protect Louisiana and the Mississippi River. It would also help them stop England and Spain from gaining too much power in the region.

After William and Mary became rulers of England in 1688, fighting between England and France increased. This made it even more urgent for France to build a settlement on the Gulf Coast. By controlling the Gulf Coast, the Alabama river valleys, the Mississippi River, the Ohio Valley, and Canada, France hoped to surround the English. This would keep the English limited to the Eastern Seaboard. The land and the valuable fur trade with Native Americans were very important.

The Le Moyne Brothers: Iberville and Bienville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville was born in Montreal. He became a hero in France for his fierce and successful attacks against the English in Canada during King William's War. With his great skills as a sailor and leader, he was the perfect choice to lead the new French settlement.

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville was Iberville's younger brother. He was very energetic and understood his duties clearly. Like other French leaders at the time, Bienville ruled with strong authority as governor of Louisiana. Even so, his followers were very loyal to him. He supported the Jesuits and also used them to his advantage. He understood Native American cultures and languages. This helped him make friends and alliances with different tribes. While usually kind, Bienville could also be tough, which made people both respect and fear him.

Two other Le Moyne brothers, Joseph Le Moyne de Sérigny and Antoine Le Moyne de Châteaugué, also helped Old Mobile. They successfully fought off attacks from Native American tribes and English and Spanish forces.

Finding the Right Spot

Soon after King William's War ended, Iberville sailed from Brest, France. He had orders to build a fort at the mouth of the Mississippi River. His brother Bienville, soldiers, and 200 colonists (including four women and children) joined him.

The Le Moyne brothers reached Pensacola Bay on January 27, 1699. They were surprised to find that Spaniards from Vera Cruz had arrived three months earlier.

The French then sailed to Mobile Point. On January 31, they anchored at the "mouth of La Mobilla." They explored a large island where they found 60 bodies. Iberville named it "Massacre Island," which was later renamed "Dauphin Island." From the top of an oak tree, Iberville saw brackish water flowing from a river into the bay. However, he didn't notice the harbor on the northeast side of the island. After deciding the bay was too shallow, they sailed on.

Next, the group visited the area of present-day Biloxi, Mississippi (or Old Biloxi). On March 2, 1699, Iberville found the mouth of the Mississippi River and sailed up it. He was looking for a good place to land. But the banks were low and marshy, so they decided it wasn't a good spot for a settlement.

Iberville went back to Biloxi and built Fort Maurepas. This was a simple fort made of squared logs. It served as his base for more exploration. After meeting English ships on the Lower Mississippi, Iberville told Bienville to build another fort. The French took over Fort de la Boulaye in 1700.

André Pénicaut, a carpenter with Iberville, wrote that "illnesses were becoming frequent" in the summer heat. This meant they needed to move to higher ground.

Pénicaut was with a scouting party that found a "spot on high ground." It was near a Native American village about 20 miles (32 km) up the Mobile River. This location was higher than Fort Maurepas. It also allowed them to be closer to the Native Americans and watch out for English traders from the Carolinas.

The French found the harbor on Massacre Island and named it Port Dauphin. They started moving the settlement from Fort Maurepas in 1702. The rivers brought a lot of silt, making the water shallow. Also, a dangerous, shifting sandbar near Mobile Point made it hard for big ocean ships to navigate. So, supplies were unloaded at Port Dauphin and then taken by smaller boats up the Mobile River.

Iberville liked the chosen location. His journals, translated by Richebourg Gaillard McWilliams, show this. He first visited the bluff on March 3, 1702, about six weeks after construction began: "The settlement is on a ridge more than 20 feet above the water. It has many different trees like white and red oak, laurel, sassafras, basswood, hickory, and many pines good for masts. This ridge and all the land around it are very good."

Iberville also wrote about the land north of the settlement: "I have found the land good everywhere, though some banks are flooded. Most of the banks are covered with very fine, tall, straight cypress trees. All the islands also have cypresses, oaks, and other trees."

He also thought the area was good for farming: "Above the settlement, I have found almost everywhere, on both banks, old Native American settlements. Farmers could settle there and only need to cut canes or reeds or bramble before they plant."

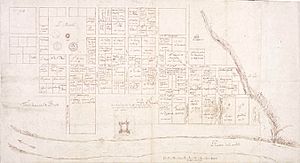

Building Mobile and Fort Louis

Charles Levasseur, a skilled draftsman who knew the Mobile area, designed and built the new fort at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff. The fort was square, with cannons at each corner. Inside, it had buildings for soldiers and officers, a house used as a chapel, and a warehouse. Behind Fort Louis de la Louisiana, a village called "La Mobile" was laid out in a grid pattern.

In 1704, Nicolas de la Salle took a census (a count of people and things). It showed that the settlement had a guardhouse, a forge, a gunsmith shop, a brick kiln, and eighty one-story wooden houses. The people living there included 180 men, 27 families with ten children, eleven Native American slave boys and girls, and many farm animals.

Struggling to Grow

Many Coureurs de bois (French-Canadian fur traders) from Canada avoided farm work. Also, the settlers often didn't know much about farming. To make up for this, they used slavery in La Mobile. At first, Native American slaves were used to clear and till the land. By 1710, La Mobile had 90 Native American slaves and servants. However, Native Americans were not always suited for the work. So, African slaves were brought in.

Because of wars (especially the War of the Spanish Succession) and England controlling the seas, it was hard for Mobile to communicate with Paris. For three years, Mobile received no supply ships from France. Even though farming was difficult, local agriculture was needed to feed the colony. To avoid starvation, people often had to go hunting and fishing. Sometimes, the French even bought food from the Spanish in Pensacola or Havana.

While the Mobilian Indians were friendly, other tribes, like the Alabama tribe, often attacked the fort and hunting parties. Thanks to Henri de Tonti, the French became good at dealing with Native American groups. Bienville used entertainment and gifts to gain their loyalty and form alliances against the English. In 1700, the French made an alliance with the Choctaw tribe. In 1702, they even managed to temporarily make peace between the Choctaws and Chickasaws. The French also interacted with the Apalachee, Tomeh, Chato, Oumas, and Tawasa tribes.

Sadly, these interactions also brought diseases. The regional Native American population dropped from 5,000 in 1702 to 2,000 in 1711. This was mainly due to smallpox and other diseases brought by the colonists.

Iberville left the region for the last time in June 1702. He later suggested to the French government that 100 "young and well-bred" women be sent to Mobile. They would marry the Canadians and help the population grow by having children. In 1704, these women (chosen from orphanages and convents), along with more soldiers and supplies, left La Rochelle on the ship Pélican.

After a difficult trip across the Atlantic, passengers caught yellow fever in Havana. As people began to die, the Pélican arrived at Massacre Island. The "twenty-three virtuous maidens," later known as "casquette girls," and their chaperones, "two grey nuns," finally reached Fort Louis. Their arrival was not as grand as anyone had hoped. The young women were not ready for the wild, undeveloped land.

The strict social classes of French society remained in the colony. This stopped people from working together, which was needed for success. The women missed French luxuries like bread and disliked things like cornbread. This led to a "Petticoat Revolution" that tested Bienville's patience. However, the French government kept sending women to boost the population. They were called "casquette girls" because some brought their belongings in small trunks called "cassettes" in French.

The yellow fever epidemic killed both Charles Levasseur and Henri de Tonti. These deaths were a big loss for Bienville and the settlement. When Iberville died of yellow fever in Havana in July 1706, Bienville became governor of Louisiana at age 27. Iberville's death was a blow to the colony. He had represented Louisiana's needs in Europe and helped the struggling town get support from the French court.

After Iberville's death, Jérôme Phélypeaux de Maurepas de Pontchartrain, a minister for colonial affairs, received complaints. Henri Roulleaux de La Vente, a priest, and Nicolas de La Salle, a royal warehouse keeper, accused the Le Moyne brothers of unfair trading. Because of these accusations, Pontchartrain appointed Nicolas Daneau, sieur de Muy, as the new governor. He also sent Jean-Baptiste-Martin D'artaguiette d'Iron to investigate. The new governor died at sea before reaching Mobile. Dartaguiette d'Iron did reach Mobile, but he couldn't prove the charges against the Le Moyne brothers. So, Bienville remained in charge of Louisiana.

By 1708, Bienville saw the growing threat from the English. The English had successfully isolated the Spanish settlement at Pensacola by destroying Native American tribes allied with the Spanish. It seemed the English would soon attack the French in a similar way. In May 1709, the threat was highest when the Alabama tribe, allied with the English, attacked a Mobilian village thirteen miles (21 km) north of Old Mobile. The Mobilians managed to drive the Alabama tribe away.

The settlers started complaining about the location of Old Mobile. They felt it was too far from the bay. Also, the land didn't drain well, and standing water remained for weeks after each rain.

Leaving Old Mobile

In 1710, an English privateer (a privately owned armed ship) from Jamaica captured Port Dauphin. They took supplies, food, and deer skins, looted the citizens, burned houses, and sailed away. Fort Louis heard the news days later by canoe. People discussed moving the fort closer to the bay and abandoning the vulnerable Port Dauphin.

In the spring of 1711, a flood rushed into Fort Louis. Soldiers and citizens had to climb trees for safety. The houses were covered up to their roofs for almost a month. This flood was the final reason for deciding to move the settlement. When the French left Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff, they burned the fort and houses. They likely destroyed the structures to stop enemies from easily using the site as a fort.

Bienville chose a new location where the river meets the bay and planned a new town. People once thought that soldiers and colonists took apart the houses and fort and moved the wood and supplies down the river. However, archaeological evidence now shows that all excavated buildings were burned where they stood. By mid-1712, the move was complete. Slowly, La Mobile turned back into wilderness.

La Mobile Town Layout

At its busiest, the town of Old Mobile (La Mobile) had about 350 people. They lived in 80 to 100 buildings. Maps from 1702 and 1704-1705 show houses spread out on large lots in a grid pattern. Iberville and Levasseur divided the land into big square blocks about 320 by 320 feet (98 by 98 metres). These blocks were then split into smaller lots of different sizes.

People were generally given plots based on their job or role in the town. For example, carpenters lived in one area, and French-Canadian fur traders lived towards the western edge. Officers and administrative staff lived close to or inside the fort. A large market square with a well was at the southwest corner of the site.

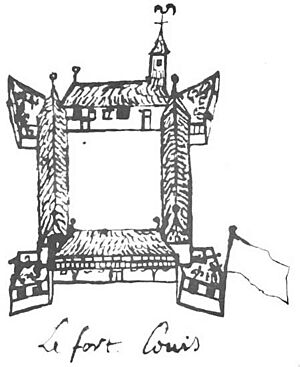

Fort Louis de la Louisiane

Fort Louis de la Louisiane was the main political, military, and religious center of the settlement. It had homes for Bienville and his officers and soldiers, a chapel, and other buildings.

André Pénicaut gave a detailed description of Fort Louis: "This fort was sixty toises [about 384 feet] square. At each of the four corners, there was a battery with six cannons. These cannons stuck out in a half circle, covering the area in front and to the sides. Inside, behind the curtains (outer walls), were four sets of buildings. These buildings were used as a chapel, quarters for the commandant and officers, warehouses, and a guardhouse. So, in the middle of these buildings, there was a parade ground forty-five toises [about 288 feet] square."

The fort's bastions (parts that stick out for defense) were built using a method called pièce-sur-pièce. In this method, wooden timbers with special ends are laid on top of each other horizontally. These ends fit into vertical grooves in posts placed regularly. A palisade fence surrounded the fort.

Because the site was damp, wooden structures quickly suffered from rot. The bastion timbers and palisade posts had to be replaced about every five years. By 1705, Bienville noted that the rotting wood made it unsafe to fire the cannons. To get ready for conflict with the English, the fort was repaired in 1707. However, within a year, the bastions were badly rotted again and could barely hold the cannons. As the English threat grew, the fort was made one-third larger. This allowed it to hold all the residents of Old Mobile and their Native American allies.

Archaeology of the Old Mobile Site

Finding the Old Mobile Site

Until the late 1900s, no one knew the exact location of the Old Mobile Site. Maps and plans from French national libraries and archives strongly suggested the site was at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff. However, some local people thought it was near the mouth of Dog River.

Based on French maps and local records, Peter Hamilton, who wrote Colonial Mobile (1910), correctly concluded the site was at Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff. He claimed to have found the well and discovered bullets, crockery, large spikes, and a brass ornament there. In 1902, Carey Butt, a friend of Peter Hamilton, visited the site. He thought he had found the powder magazine of Fort Louis. Based on these findings, the Iberville Historical Society put up a monument at the site in 1902. This was part of the celebration for Mobile's 200th anniversary.

Archaeological Digs and Surveys

In 1970, the University of Alabama, led by Donald Harris, did the first archaeological survey of the site. This survey lasted two weeks in an area just north of the monument. Harris found a foundation, which he incorrectly thought belonged to Fort Louis. He also found Native American pottery and small iron cannonballs.

In the mid-1970s, the Old Mobile Research Team was formed. James C. "Buddy" Parnell started the group with friends and co-workers from Courtaulds Fibers. This company owned part of the suspected Old Mobile site. The team realized that Donald Harris had been looking in the wrong place. Using clues from aerial photographs and French maps, the team found a house from the old settlement in February 1989. They also discovered other items like pieces of dinnerware, clay pipe stems, and bricks.

In May 1989, the Old Mobile Project started. It was a community effort involving Mobile County, the city of Mobile, and the University of South Alabama. Money for the project came from private groups, university funds, the Alabama Historical Commission, and government grants. The landowners of the Old Mobile Site (Courtaulds Fibers, DuPont, Alabama Power Company) allowed excavations. In June 1989, digging began under the direction of Gregory A. Waselkov. While earlier efforts helped find the exact location, the Old Mobile Project surveys found the most archaeological evidence.

What Archaeologists Found

Archaeologists used shovel testing to find out how big the site was and where buildings were located. From 1989 to 1993, they did about 20,000 shovel tests, spaced thirteen feet (4.0 m) apart. Since 1989, they have found the locations of more than 50 buildings and the approximate borders of Old Mobile. Eight of these sites have been partly or fully dug up. The exact locations of Fort Louis or the settlement's cemetery have not been found. Archaeological surveys show that a part of Old Mobile on the east side, possibly including parts of Fort Louis, was lost to river erosion.

Buildings were built using two main methods: poteaux-en-terre and poteaux-sur-sole. In poteaux-en-terre (posts in the ground) construction, wooden posts are placed vertically into the ground. The spaces between the posts were filled with a mix of mud or clay and Spanish moss or hay. Small rocks could also be added. The walls were held together by a top beam and covered with plaster or siding.

In poteaux-sur-sole (posts on a sill) construction, the floor of the building was raised using a bottom sill. This sill was made by laying wooden pieces directly on the ground. Raising the floor created an air space that helped prevent damage from moisture and insects. Since the site's conditions were bad for wood, poteaux-sur-sole buildings were better. Their sill pieces could be replaced more easily than the posts of a poteaux-en-terre structure. Trenches outside some buildings suggest that palisade fences were used around them.

In the summer of 1989, archaeologists dug up a house site near the western edge of the site. This house, thought to be lived in by French Canadians, was a long, narrow building. It had a living room with two bedrooms on either side, and a fenced garden or animal pen at one end. The only parts left of the house were the footing trenches for the wall sills, clay floors, and brick pieces from a fireplace.

During the 1990 field survey, a blacksmith shop was found. This was identified by finding large amounts of iron scrap, slag, coal, and charcoal.

These digs have also found thousands of artifacts. A lead seal from 1701, with the name "Company of Indies of France" and a fleur-de-lis, was used to identify property. It helped confirm that the settlement's location was correct.

Other items found include:

- Building materials: fired wall clay (called bousillage), roof tiles.

- Dishware: French faience, Mexican majolica, Chinese porcelain, kettle pieces, wine glasses.

- Weapons: French gun flints, lead shot, gun and sword parts.

- Clothing items: brass and silver buttons, shoe and clothing buckles.

- Money: French and Spanish coins, glass trade beads.

- Ceremonial items: catlinite pieces from ceremonial pipe bowls.

Building Styles

The town was built on a grid pattern. Each block had 2 to 10 individual lots, separated by dirt streets about 12 meters (40 feet) wide. Nine buildings have been fully dug up, and many others partly. Old Mobile had over 100 separate buildings at its peak, with different jobs and families living in them.

For example, Structures 1, 3, and 5 on the western side were homes. Structure 2 was a blacksmith shop, shown by a forge. Structures 4 and 14 were likely taverns. Structures 30-32 were probably military barracks. These buildings used different construction methods like poteaux-en-terre, poteaux-sur-sole, and piéce-sur-piéce. The method depended on who was building them and who lived there.

Roofs were often made of river cane or wooden shingles and covered with palmetto. Some buildings had terracotta tiled roofs, but this wasn't common. Spaces between timbers were filled with a mix of clay and Spanish moss. This means there were large pits near many buildings where clay was dug. These pits later became middens (trash heaps) for the people living there. Accidental fires and natural disasters often destroyed houses. These houses were either left or fixed, depending on the damage.

Soldiers played a big part in building Old Mobile. Many were young, sometimes 13 or 14, and untrained. They joined the military out of need or were taken from prisons (though these were usually adults). These troupes de la marine had to go overseas to colonies like Old Mobile. Many lived near Fort Louis. Their job was to protect the colony, but many were untrained and underpaid, similar to indentured servants. So, they had to build, repair, and maintain parts of the town, including their own garrisons.

Structures 30-32 were likely built by soldiers for themselves. They were close to Fort Louis. Their poteaux-en-terre construction shows they were temporary and easy to build, especially by untrained soldiers. These were fenced-in buildings. Structure 30 had several small sections too tiny to be rooms. Because of how it was built and the many artifacts found inside, it was probably a storage building.

Plant and Animal Remains

Archaeologists found many plant and animal remains at the site. These tell us about how the colonists got their food. Historical records show that colonists were not very good at growing their own food. A census in 1704 listed: 9 oxen, 4 bulls, 14 cows, 5 calves, 3 kids (young sheep), about 100 pigs, and about 400 chickens. A 1708 census listed: 8 oxen, 4 bulls, 50 cows, 40 calves, about 1400 pigs, and about 2000 chickens. Historical records suggest most of these animals were shipped to the colony, not raised there.

A sample of animal bones from Structures 1-5 had 47,348 individual pieces, weighing 3 kg. However, the buildings were likely burned when the site was left in 1711. Also, the climate and acidic soil (average pH 5.5) meant bones didn't preserve well. Most bones were broken and calcined (burned), so only 0.5% could be clearly identified.

Of the bones that could be identified, 93% were from mammals. These included white-tailed deer, pig, black bear, opossum, muskrat, beaver, squirrel, and dog (dogs were not eaten). 5.1% of the bones were from birds, while turtles and fish were less than 1%. The largest groups of bones were from domesticated animals (pig and chicken). But wild game, waterfowl, and shellfish were much more common overall. This suggests that French shipments were unreliable. So, colonists relied heavily on wild game, which they hunted or got from local Native American tribes.

Plant remains were found mainly in pits, middens, and trenches. They were studied using flotation samples. Like most ancient plant evidence, some items might be underrepresented or overrepresented depending on how well they preserve. For example, flour doesn't preserve well, but maize preserves much better than beans. Most plant remains at this site were heavily carbonized (burned). This means they were either cooked and thrown in trash heaps, or burned when the site was abandoned.

Domesticated plants were a major part of the colonists' diet. Maize (corn), the main food, was the most common plant found. The size of the corn kernels and rows per cob match local and foreign maize types. This suggests that the maize at Old Mobile was grown locally, either by colonists or Native American groups. Other local foodstuffs included fruits like sumac, plum, persimmon, black gum, and grape, as well as several nuts. These were likely traded from Native Americans or gathered by colonists. European plant remains were also found, especially the fava bean. These beans are common in Mediterranean and European cooking. They were likely imported and grown in the moisture-rich soils of Old Mobile. Peaches were also brought to the colony, but evidence suggests they were often used for trade rather than food.

There weren't big differences in the types of plants found at different buildings. Most showed a syncretic (mixed) subsistence system. They used local maize and imported beans as main foods. These were then added to with local fruits and nuts. Historical records (like journals and trade logs) show that colonists preferred trading for goods over growing them. This was because foreign aid was unreliable. Since both local Native American groups and European colonists relied on women to prepare meals, it's likely that Native women taught colonial women how to find and prepare local plants.

European Artifacts

Digs at Structure 30 found many Native American and European artifacts. While Native American pottery was preferred (making up about 64% of all pottery found), several other types of European artifacts were found. Many of these were used for trade with local groups. Here are some types of artifacts found:

- Tin-glazed Vessels:

* Normandy Plain * St. Cloud Polychrome * Nevers Polychrome

* Abó Polychrome * San Luis Polychrome * Puebla Polychrome * Note: Most plateware found looks like Spanish designs.

- Lead-Glazed Course Earthenware:

* Green-glazed (from Southwestern France) * Other glaze types showing French making * Few Spanish and English styles

- Pipes (very common, often made with red pipestone):

* European white-clay designs (sometimes with craftsman's initials) * Native American designs (often with artistic designs or craftsman's name)

- Metal:

* Copper and brass decorations * Swords (brass) * Lead Rupert Shot (likely made on-site)

- Glass:

* Mostly olive-green (French-made) * Beads (see below)

* Rare but present

About 2,500 glass beads were found in six different buildings. Most came from colonial areas. These beads were worn by both colonists and Native Americans. They became important trade goods. They also helped archaeologists figure out dates for glass beads found at French colonial sites in the Americas. Some beads found match beads from Spanish mission sites to the south. This matches the idea of Apalachee Native Americans fleeing Spanish persecution and bringing their beads with them. European glass beads are found at Old Mobile, nearby Native American sites, and across the United States. Since Old Mobile was one of the first true French colonies in the US, bead making and movement can be traced back to it. This means the beads found here can help date other bead studies in nearby French colonial sites.

Interactions with Native Tribes

The relationship between the colonists and nearby Native American groups was helpful for both sides. Without help from these groups, the colony likely would have failed. While Native American slaves were kept at the site, their numbers decreased as more women and wives came from France. The French colonists at Old Mobile did not allow the enslavement of Native Americans who were allied with them.

Seeing how the English treated Native Americans, the French saw a chance to build good relationships with local tribes (Mobilian, Apalachee, Tomé, Naniabas, Chatos). They offered a different kind of relationship. Old Mobile became a safe place for some groups who wanted to avoid English enslavement.

Most artifact evidence points to a good relationship with the Apalachees. This is shown by Lamar Complicated Stamped and Marsh Island Incised pottery styles, as well as Spanish Glass Beads. However, historical evidence suggests an even stronger relationship with the local Mobilian peoples. This is seen in trade reports, the trade language, the site name, and Port Dauphin Incised pottery. In fact, 64% of the pottery at the site came from Native craftsmen. Historical documents mention frequent and helpful trade deals with nearby tribes. Unfortunately, the pottery trade isn't well recorded in trade logs. This might mean these were low-cost deals, and colonists didn't value Native pottery highly in terms of money.

French settlers largely depended on Native Americans for wild game when their food supplies were low. Native groups provided maize (corn), venison (deer meat), furs, deerskins, and pottery. French colonists provided beads, catlinite pipes, guns, knives, and nails.

Sometimes, Native Americans lived in European buildings. They might have been slaves, but also teachers, wives, or part of the family. Colonists didn't know everything about the land. So, Native groups likely taught them how to grow and prepare local resources. Some soldiers even asked their commanders if they could live with Native groups, as housing for soldiers around Fort Louis was hard to manage. Soldiers especially relied on Native Americans during winter. They often couldn't afford new uniforms and wore deerskin and fur made by Native Americans instead.

Native Americans were not forced to become like the French colonists. While some did adopt European ways of crafting or hunting, most kept their cultural traditions. Even the language spoken by the two groups to communicate (a Pidgin language) was mainly Mobilian, with some French and Spanish words added. The two cultures influenced each other. Native groups became more colonial in their appearance, and French colonists changed their cooking habits to be more like Native foodways.

The interactions between Native groups and French colonists at this site set an example for future French settlements. While some tribes were not as friendly, the Old Mobile site shows positive relations and a mixing of cultures in early French colonial societies.

Structure 1MB147

One special building, 1MB147, in the Northwest Corner of the town, is known to have housed a Native American family. This building is unique because it shows little European influence. It was built differently from other houses in town. It faces the cardinal directions instead of following the town's grid system. Its foundations are much shallower and simpler than the colonial designs. Animal remains from the site show that whoever lived there did not eat any domesticated animals.

There are actually fewer Native artifacts found at this site, and more European artifacts. This suggests that the people living here traded a lot with their colonial neighbors. This building also supports what historical records say: Native people lived just outside the town's edge to trade more easily. Native Americans living in such buildings were not forced to do so. The differences in this building's construction show that Native Americans kept many of their original ways of life. They did not have to give in to forced assimilation.

Old Mobile's Legacy for French Colonialism

The Old Mobile site helps us understand French colonialism in the American South. Unlike some other imperialist countries, French culture did not completely take over Native culture where they interacted for long periods. Instead, a form of cultural mixing happened, changing both cultures and creating something new.

Using this site as a starting point, we can examine dates from plant and animal evidence, as well as from glass beads and other European artifacts. Native American artifacts found at the site can help trace France's influence across America.

It's important to look at French colonialism from different angles, including the experiences of women. French colonial culture could not have survived without Native support. Plant and animal evidence suggests that Native Americans were ready and willing to help the colonists survive. Artifacts show a huge economic connection between the two groups. Further study of how they got food shows the important role of women, especially Native women. Without them, colonists would not have known how to cook and prepare local ingredients. Shipments from France and Spanish colonies added to the variety of artifacts. They also helped spread artifacts throughout the American South.

Old Mobile was a strong center of French culture and trade during the earliest times of settlement on the Gulf Coast. The survival techniques, and changes in language and ways of life learned here continued in later settlements. These include present-day Mobile, Port Dauphin, and sites along the St. Lawrence river valley.

Images for kids

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |