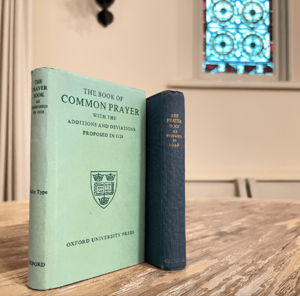

Book of Common Prayer (1928, England) facts for kids

The 1928 Book of Common Prayer, also called the Deposited Book, was a special church service book. It was suggested as a new version of the Church of England's main prayer book from 1662. Some people, called Anglo-Catholics, wanted to make the church services more like those in the Catholic Church. They especially wanted to allow a practice called the reserved sacrament, where consecrated bread and wine are kept after a service.

However, many Protestant evangelicals and nonconformists in Parliament strongly disagreed. They saw these changes as making the Church of England too similar to the Catholic Church. This disagreement led to a big conflict known as the Prayer Book Crisis.

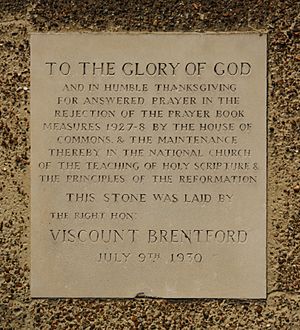

The new prayer book was voted on twice in the House of Commons, once in December 1927 and again in June 1928. Both times, it failed to pass. This was a big blow to the Church of England's authority. Even though Parliament never approved it, the 1928 prayer book became very popular and was widely used in churches during the mid-1900s. The story of this proposed book and its failure in Parliament has affected how Anglican churches in England and other countries create and update their service books.

Contents

Why Change the Prayer Book?

Old Ways and New Ideas

The Church of England's main service book, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, had been used for a long time. But by the late 1800s, some church members, especially a group called Tractarians and later Cambridge Movement members, felt it was too "Protestant." They wanted to bring back older, more traditional practices from the Catholic Church.

These practices included things like the priest facing east during Communion, putting candles and a cross on the altar, and wearing special vestments (robes). They believed these "usages" were allowed by the prayer book's rules. These ideas from Anglo-Catholics pushed for changes to the prayer book.

Concerns and Conflicts

Around the 1870s and 1880s, some clergy started using medieval Catholic services. This made some people worried about how loyal Anglo-Catholics were to the Church of England. John Henry Newman, a famous Tractarian, even joined the Catholic Church, which increased these worries.

Protestant evangelicals wanted to make sure the prayer book was clearly Protestant. This led to new laws in the 1870s that tried to stop some of the new ceremonial practices. Some priests were even sent to prison for not following these rules. But soon, people felt these courts were too harsh, and bishops stopped sending priests to them.

In the 1890s, a man named John Kensit and his Protestant Truth Society strongly challenged Anglo-Catholics. They were supported by groups like the English Church Union. Even though the Archbishop of Canterbury, Frederick Temple, had approved some Anglo-Catholic practices, politicians tried to stop them. In 1900, a rule was made to ban the reserved sacrament (keeping consecrated bread and wine) and the use of incense in worship.

Looking for Answers

Despite these bans, Anglo-Catholics kept studying old church practices. The Alcuin Club, started in 1897, researched the history of the prayer book. They often looked at practices from before the English Reformation and even the first centuries of Christianity. Scholars used this research to argue that the 1662 prayer book was outdated. They preferred older, more "primitive" ways of worship.

At the same time, the language in the 1662 prayer book was becoming old-fashioned. Many phrases were hard for people to understand. This made it difficult for pastors to explain the services. Because of these problems, more and more Church of England clergy wanted to update the prayer book.

In 1903, Randall Davidson, the Archbishop of Canterbury, promised to control the Anglo-Catholics. A special group was formed in 1904 to review church rules. Their report in 1906 said that the church's worship rules were "too narrow" for modern life. It also said that the ways to enforce rules were not working. The report suggested revising the rules for vestments, which officially started the process for a new prayer book.

The Revision Process

Early Efforts (1906-1914)

At first, the revision focused on the rules about vestments and how they were used to justify Anglo-Catholic ceremonies. A group of bishops, led by John Wordsworth and helped by liturgist Walter Frere, said in 1908 that chasubles (a type of vestment) were legal. This caused protests.

In 1911, Archbishop Davidson set up a committee to look into church services. They tried to include people with different views, like the evangelical bishop Thomas Drury and Anglo-Catholics like Frere and Percy Dearmer. Many scholars published books about church history during this time. These scholars wanted to protect the Anglican identity as being "both catholic and reformed."

In February 1914, the bishops' report was published. But soon, World War I started, which slowed down the work. Archbishop Davidson wasn't very interested in the revision, seeing it as a distraction. During the war, the church leaders continued to review possible changes. One idea was to move the Prayer of Oblation in the Communion service, making it more like older prayer books.

Impact of World War I

The war actually sped up the need for bigger changes. Keeping the consecrated bread and wine (reserved sacrament) became more common during the war. This was because it was easier for chaplains to give Communion to sick or injured soldiers. Even though it was popular, evangelicals strongly disliked this practice, seeing it as "Romish."

Also, the old-fashioned language of the 1662 prayer book was not comforting to soldiers, many of whom could barely read. The services also felt boring and repetitive. People felt that the usual Church of England worship was "too dull and cold" for those struggling in difficult times. These problems meant that the small changes suggested before the war were no longer enough.

After the War

After the war, chaplains and those working with the working class saw a need for a simpler, more modern, and easier-to-understand church service. However, when the main revision work began, these practical concerns were often ignored. Instead, academics focused on old debates between evangelicals and traditionalists. Many also felt that the language of the 1662 prayer book and the King James Version of the Bible was sacred and shouldn't be changed. So, the language wasn't fully modernized until the 1960s.

In 1919, a new law created the National Assembly of the Church of England. This assembly had clergy and lay people (church members who are not clergy). The National Assembly started a committee for prayer book revision in 1920. Their report was published in 1922. The bishops approved these recommendations, including allowing the reserved sacrament.

After this, three main groups outside the official committee tried to influence the final prayer book. These proposals were known by the color of their covers: the "Green Book," the "Grey Book," and the "Orange Book."

The Green Book (1922) was from an Anglo-Catholic group and wanted more traditional practices. The Grey Book (1923) was from the Life and Liberty Movement and had a more modern, liberal Anglo-Catholic view. The Orange Book (1923-24), mostly by Walter Frere, tried to combine the ideas from the other proposals. All three proposals allowed the reserved sacrament.

Protestant evangelicals continued to oppose the changes. Many simply wanted to keep the 1662 prayer book as it was. They especially disliked the idea of moving the Prayer of Oblation, adding an Epiclesis (a prayer asking the Holy Spirit to bless the elements), and allowing the reserved sacrament. Several bishops, like Ernest Barnes, strongly opposed these ideas.

The National Assembly finished its revisions in 1925. The bishops then spent 47 days working on the revision. Archbishop Davidson received 800 letters about the changes. Some bishops even opposed any changes to the Communion service.

The bishops' final version was sent to the church leaders in February 1927. After some more changes, it was approved by the National Assembly in July 1927. Now, the public started paying attention. Anglo-Catholics and evangelicals both opposed the new book, but for opposite reasons. Anglo-Catholics thought it was too Protestant, while evangelicals thought it was too "popish" (too Catholic).

The Prayer Book Crisis

A Question of National Identity

By 1927, the debate over the prayer book became a big question about England's identity. Many Anglicans felt that the Church of England was deeply connected to being English.

Anglo-Catholics argued their practices were traditional English customs. But others worried about keeping England's Protestant character. They saw Protestantism as the foundation of the relationship between the monarchy, Parliament, and the church. They pointed to the king's coronation oath, which promised to protect the Protestant religion. Some feared that the Catholic Mass might even become the coronation service for a future king.

Parliament's Role

The Church of England is the official state church, which meant Parliament had to approve the new prayer book. Unlike the Church of Scotland, which had more freedom, the Church of England needed Parliament's permission for big changes. This was a problem because Parliament was no longer mostly Anglican. More and more members were Catholics, non-Christians, or nonconformist Protestants.

The proposed prayer book was sent to Parliament's Ecclesiastical Committee in 1927. This is why it was called the Deposited Book. The committee said the changes were not a big deal and kept the promise to maintain the Protestant religion.

Archbishop Davidson presented the prayer book to the House of Lords on December 12, 1927. After a three-day debate, the House of Lords approved it.

The House of Commons Says No

Everyone expected the House of Commons to approve it easily. But evangelical opponents had been planning their resistance. On November 30, a meeting of about 100 members, led by Home Secretary William Joynson-Hicks (known as "Jix"), was held.

On December 15, Jix gave a powerful speech. He called the alternative Communion service "medieval" and said that the reserved sacrament would always lead to worshipping the bread and wine. Rosslyn Mitchell gave another important speech, saying the Deposited Book promoted the Catholic idea of transubstantiation (that the bread and wine truly become the body and blood of Christ).

Even though Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin spoke in favor, their appeals failed. After a seven-hour debate, the House of Commons voted against the prayer book, 238 to 205. Archbishop Davidson was very upset, feeling it damaged the church's authority. One person later said that "in a single hectic night the House of Commons had apparently destroyed the work of more than twenty years."

Even though he wasn't very interested in the changes, Davidson and others felt a new prayer book could pass if they made some changes that were more Protestant. Some Anglo-Catholic changes were removed. However, the second attempt also failed in the House of Commons on June 14, 1928, with an even larger majority against it (266 to 220). Joynson-Hicks said that the "question of Reservation was the crux of the whole matter" for both attempts.

Impact Outside England

The debate also reached the Church in Wales, which is separate from the Church of England. In 1927, the Archbishop of Wales A. G. Edwards said that decisions made in England had no power in Wales. He declared that only the prayer book approved by the Church in Wales was legal. While there was a push to consider the English Deposited Book in Wales, the bishops intentionally delayed, and the issue wasn't revisited until 1943.

The controversy also affected churches in Scotland. Even though the Church of Scotland is Protestant, the reserved sacrament was an accepted practice there. The leader of the Episcopal Church of Scotland, Walter Robberds, refused Archbishop Davidson's request to ask Scottish politicians to vote for the English revision. The English debate might have also increased anti-Catholic feelings in Scotland.

What Happened Next?

After the Rejection

After Parliament rejected the prayer book, many churches started using services that Parliament had not approved. In 1929, the bishops allowed clergy to use the Deposited Book "during the present emergency." A shorter version, the Shorter Prayer Book, became popular in 1947.

Finally, in 1958, the bishops formally approved the use of the Deposited Book's prayers and practices. By 1959, many English clergy were using parts of the 1928 prayer book. This approval was meant to happen with the "goodwill" of the church members.

Some of the most popular parts of the 1928 book that were adopted included the reserved sacrament, and revised services for baptism, marriage, and burial.

Influence on Other Churches

The proposed 1928 prayer book also influenced other Anglican churches around the world. For example, the 1929 Scottish Prayer Book borrowed many ideas from the Deposited Book. In the Church of Nigeria, a prayer book combined parts of the 1662 and 1928 English prayer books. The Nigerian church's 1996 prayer book also used the 1928 revision's service for Administering to the Sick.

New Ways of Worship

In the 1960s, there was a new push for more modern church services. The idea of "permissive alternatives" became popular, meaning churches could choose different ways to conduct services. Many services from the 1928 book were put into the Church of England's 1966 First Series of Alternative Services.

In 1970, the General Synod gained the power to change church services without Parliament's approval. In 1974, the church adopted the Worship and Doctrine Measure, which led to the 1980 Alternative Service Book. This book was called "Alternative Service Book" to avoid needing Parliament's involvement, which would have been required for a new "Book of Common Prayer."

So, the 1662 prayer book, with only small changes, remains the only Book of Common Prayer officially approved by the Church of England. The Alternative Service Book was later replaced by the Common Worship books, which are used today.

What Was Inside the 1928 Book?

The 1928 proposed prayer book had some important differences from the 1662 version. The introduction was likely written by Archbishop Davidson. Like the 1662 book, it used the Psalms from the 1540 Great Bible, not the 1611 King James Bible.

Reserved Sacrament and Vestments

The rules about the reserved sacrament were very controversial. The 1927 revision allowed the reserved sacrament only for giving Communion to sick people who couldn't receive it otherwise. These rules were written to prevent other uses, and it also said that bishops had to approve the practice. It was illegal to worship the reserved sacrament outside of a service.

The new rules for vestments also caused debate. Bishop Arthur Headlam said in 1927 that the new rules were meant to bring "peace" and "order." He noted that it was impossible to ban Eucharistic vestments. The allowed vestments included the chasuble, cope, and surplice.

Calendar and Readings

The new book introduced a Table of Proper Psalms, which assigned specific psalms for all Sundays and some holy days. This made the psalms more relevant to the day's theme, but it broke the old system where every psalm was read each month. Many new saints' days were added to the calendar of saints, though a few were removed. The number of vigils (days before a feast day) that required fasting was reduced to five.

The House of Clergy had approved a day for Corpus Christi Day, a Catholic feast, but the House of Laity rejected it. Instead, they allowed for an unfixed thanksgiving for the two Anglican sacraments: Holy Baptism and the Holy Communion.

Daily Services

To make the Morning and Evening Prayer more varied, 19 new sentences with seasonal themes were added. The old-fashioned language of the Confession and Absolution was updated with alternative forms. A third option was the simple sentence "Let us confess our sins to Almighty God." The book also allowed the introduction to be skipped if another service followed immediately.

The 1662 prayer book's daily services ended with "The Grace" from 2 Corinthians 13. The revised text allowed for three alternative endings after the Prayers and Thanksgivings.

A new translation of the Athanasian Creed was included as an option. It was suggested for recitation on 15 days, but it also became optional on all these days. It could even be split into two parts, leaving out the "damnatory clauses" (parts that sound like they condemn people). This meant that in most churches, the Athanasian Creed was only said on Trinity Sunday, or often not at all.

Holy Communion Service

The revised prayer book had two Communion services: the original 1662 service and a new, revised one. The new service borrowed ideas from older prayer books, including an Epiclesis (a prayer asking the Holy Spirit to bless the bread and wine). The Gloria in Excelsis (a hymn of praise) could be skipped on weekdays, just like in the 1549 prayer book.

Ordination Services

The 1928 ordinal (the service for ordaining clergy) was mostly based on an earlier proposal. It suggested that the litany (a series of prayers) could be shorter for ordinations. It also suggested a new version of the hymn "Come, Holy Ghost."

The rules for consecrating bishops now said it should only happen on holy days or Sundays. A new prayer was added for ordaining deacons and priests at the same time.

In 1924, a service for making deaconesses was approved by church leaders. This service was included as an appendix to the bishops' proposed prayer book. However, it was removed in 1927 because it had not been approved by the National Assembly. In 1937, it was decided that a service for making deaconesses would be added to the ordination services of any new prayer book.

See also

- Bishops' Wars – A conflict partly caused by a prayer book revision

- Book of Common Prayer (Unitarian) – Some earlier private changes to the 1662 prayer book

- Jenny Geddes – A person in the 1600s who opposed prayer book services

- Prayer Book Rebellion – A conflict that started when the 1549 prayer book was introduced

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |