Women's suffrage in the United Kingdom facts for kids

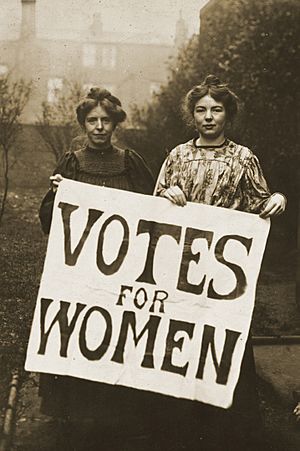

For many years, women in the United Kingdom fought for the right to vote. This movement finally succeeded with new laws in 1918 and 1928. It became a big national effort during the Victorian era. Before 1832, some women could vote, but the Reform Act 1832 and the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 stopped them.

By 1872, the fight for women's voting rights became a national movement. Groups like the National Society for Women's Suffrage and later the more powerful National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) were formed. In places like Wales and Scotland, similar movements also grew. By 1906, many people started to support women's right to vote. This led to the start of a more active, or "militant," campaign with the creation of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU).

When World War I began in 1914, political activities, including the suffragette campaigns, paused. However, quiet discussions continued. In 1918, the government passed the Representation of the People Act 1918. This law allowed all men over 21 to vote. It also gave women over 30 who owned property the right to vote. This act was a huge step, adding 5.6 million men and 8.4 million women to the voting list. Then, in 1928, the government passed another law, the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928. This law gave all people, men and women, over the age of 21 the right to vote, making voting rights equal for everyone.

Contents

Early Steps Towards Voting

Before 1832, a few women who owned property could vote in elections, but this was very rare. After the 1832 law, women lost their right to vote in local elections too. However, in 1869, single women who paid taxes got the right to vote in local elections. This right was confirmed in 1894 and even included some married women. By 1900, over 1 million women in England could vote in local elections.

There were some people who believed women should vote in national elections even before the 1832 law. After the law, a politician named Henry Hunt argued that single, tax-paying women with enough property should be allowed to vote. He used the example of a wealthy woman named Mary Smith.

The Chartist Movement in the late 1830s also had some supporters of women's voting rights. Some believe that William Lovett, one of the writers of the People's Charter, wanted to include women's suffrage. But he decided not to, fearing it would slow down their main goals. Most women at this time were not actively seeking the right to vote.

In 1843, a record book showed thirty women's names among those who voted. These women were active in the election. One wealthy woman, Grace Brown, a butcher, had four votes because of the high taxes she paid.

In 1867, Lilly Maxwell, a shop owner, famously cast a vote. Her name was mistakenly added to the voting list because she met the property rules that would have allowed a man to vote. She voted in a special election, but her vote was later declared illegal. This case brought a lot of attention to the women's suffrage movement.

At this time, the fight for women's voting rights was part of a larger movement for women's rights. Women were pushing for other changes, like the right to sue an ex-husband after divorce (achieved in 1857) and the right for married women to own property (fully achieved in 1882).

The idea of changing voting laws became important again when John Stuart Mill was elected to Parliament in 1865. He openly supported women's right to vote.

Peaceful Protests Begin

In 1865, the same year John Stuart Mill was elected, the first women's discussion group, the Kensington Society, was formed. They discussed whether women should be involved in public life.

Later that year, Leigh Smith Bodichon started the first Women's Suffrage Committee. In just two weeks, they gathered almost 1,500 signatures supporting women's voting rights for a new law.

The Manchester Society for Women's Suffrage was founded in 1867. Its secretary, Lydia Becker, wrote letters to the Prime Minister and newspapers. She also helped the London group collect more signatures.

In June 1867, the London group split due to different political views and strategies. Some wanted to move slowly, while others wanted faster change. As a result, Helen Taylor formed the London National Society for Women's Suffrage, which worked closely with groups in Manchester and Edinburgh. In Scotland, one of the first groups was the Edinburgh National Society for Women's Suffrage. These early groups were known as "suffragists" and used peaceful methods.

In Ireland, Isabella Tod started the North of Ireland Women's Suffrage Society in 1873. Her efforts helped women in Belfast get the right to vote in local elections in 1887, eleven years before other women in Ireland. The Dublin Women's Suffrage Association was formed in 1874. It worked to improve women's roles in local government and changed its name in 1898 to reflect this.

Early Efforts in Parliament

In 1868, John Stuart Mill presented a petition to Parliament with over 21,000 signatures asking for women's voting rights. In 1870, a bill was introduced that would have given women the right to vote on the same terms as men, but it was defeated. Over the next few decades, many similar bills were brought to Parliament. From 1886 onwards, most politicians supported women's suffrage. However, without strong government support, these bills often failed to become law.

Between 1910 and 1912, three "Conciliation Bills" were proposed. These bills offered women a more limited right to vote based on property. The 1912 bill was defeated, and the Women's Social and Political Union blamed Prime Minister H. H. Asquith and other Liberal politicians for its failure.

Women's Political Groups

Women's political party groups were not formed just for women's suffrage, but they had two important effects. First, they showed that women could be skilled in politics. Second, this made the idea of women voting more accepted.

Primrose League

The Primrose League (1883–2004) promoted Conservative ideas through social events. Women from all social classes could join and meet local and national politicians. Many women also helped bring voters to the polls. This helped women become more politically aware, even though the League itself did not specifically push for women's voting rights.

Women's Liberal Associations

These groups, like the first one in Bristol in 1881, sometimes aimed to promote women's voting rights. They worked separately from men's groups and became more active under the Women's Liberal Federation. They sought support for women's suffrage from all social classes. Many Liberal politicians supported women's suffrage, but a few leaders, especially H. H. Asquith, blocked efforts in Parliament.

National Movement Takes Shape

The campaign for women's voting rights became a national movement in the 1870s. At this time, all campaigners were "suffragists," meaning they used peaceful, legal methods. They tried to convince politicians to introduce bills in Parliament. However, these bills rarely passed, making this approach often ineffective.

In 1868, local groups joined to form the National Society for Women's Suffrage (NSWS). This was the first attempt to create a united front for women's suffrage. But the group faced several splits, which weakened the campaign.

Until 1897, the campaign remained relatively small. Campaigners were mainly from wealthy families. In 1897, the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was founded by Millicent Fawcett. This group connected smaller organizations and used peaceful methods to pressure politicians who did not support women's suffrage.

The Suffragettes and Stronger Actions

The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was started in 1903. It was tightly controlled by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst. The WSPU became known for its highly visible public campaigns, like large parades. These actions brought a lot of energy to the entire suffrage movement. Even though most politicians in Parliament supported women's suffrage, the ruling Liberal Party refused to allow a vote on the issue. This led the WSPU to use more forceful methods.

The WSPU, unlike its allies, began a campaign of property damage to draw attention to the issue. Their tactics included shouting at speakers, going on hunger strikes, throwing stones, breaking windows, and damaging unoccupied buildings. In Belfast, when a political group seemed to go back on their promise to support women's suffrage, WSPU members damaged buildings and sports facilities. In July 1914, a WSPU member named Lillian Metge damaged Lisburn Cathedral.

Some historians believe that these militant actions actually harmed the cause of women's suffrage. Others argue that by 1913, the WSPU focused more on their strong actions than on getting the vote itself. Their fight with the Liberal Party became so important that they didn't stop, even if it meant delaying suffrage reform. This focus on direct action set the WSPU apart from the NUWSS, which continued to focus on getting women the right to vote.

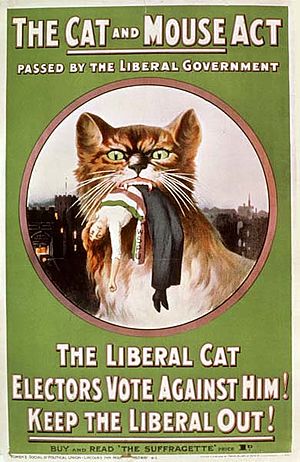

The Cat and Mouse Act was passed in 1913. This law allowed suffragettes on hunger strike to be released from prison when they became very ill. Once they recovered, they would be sent back to prison. This law was meant to stop suffragettes from becoming heroes by dying in prison, but it actually brought even more attention to their cause.

Women's Role in World War I

When World War I began, most of the larger suffrage efforts paused. The NUWSS continued to lobby peacefully. Emmeline Pankhurst believed Germany was a danger to everyone, so she convinced the WSPU to stop all militant suffrage activities.

Parliament Expands Voting Rights in 1918

During the war, there was a big shortage of men available for work. Women stepped up and took on many jobs traditionally done by men. With the agreement of trade unions, factory jobs were simplified so that less skilled men and women could do them. This led to a large increase in women working, especially in factories making war supplies. This helped society see what women were capable of.

Some people think that women were given the vote in 1918 because the strong actions before the war had stopped. Others believe that politicians had to give at least some women the vote to avoid the militant actions starting again after the war. Many major women's groups strongly supported the war effort. However, the Women's Suffrage Federation, led by Sylvia Pankhurst, was against the war and set up co-operative factories and food banks to help working-class women.

Before this time, voting rights for men were often based on their jobs. Millions of women were now doing these jobs. The old voting rules were outdated, and there was a general agreement to change them. For example, a man who joined the army might lose his right to vote. In early 1916, suffrage groups quietly agreed to work together. They decided that any new law expanding voting rights should also include women.

A special committee from all political parties, called the Speakers Conference, met in secret in October 1916. They decided that some women should get the vote, but at a higher age. Women leaders accepted a voting age of 30 to ensure most women would get the vote.

Finally, in 1918, Parliament passed a law giving the vote to women over 30 who owned a house, were married to a householder, rented property worth £5 a year, or were graduates of British universities. About 8.4 million women gained the right to vote. In November 1918, another law was passed, allowing women to be elected to Parliament. By 1928, most people agreed that giving women the vote had been a success. In 1928, the Conservative government passed the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928. This law gave all women over 21 the right to vote, making voting rights the same for men and women.

Important Women Who Led the Way

Emmeline Pankhurst was a very important figure who brought a lot of media attention to the women's suffrage movement. With her two daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, she founded and led the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). This group focused on direct action to win the vote. Emmeline's husband, Richard Pankhurst, also supported women's voting rights. He wrote the first British bill for women's suffrage and laws about married women's property. After her husband died, Emmeline became even more involved in the fight. She founded the Women's Franchise League in 1889 and the WSPU in 1903. Frustrated by years of inaction from the government, the WSPU adopted strong, direct methods. These methods were so powerful that they were later used in suffrage movements around the world. Emmeline died shortly after women finally gained the right to vote.

Another key leader was Millicent Fawcett. She believed in a peaceful approach to achieving women's rights. She supported the Married Women's Property Act 1870 and campaigns for social purity. Two events made her even more involved: her husband's death and a split in the suffrage movement. Millicent believed in staying independent of political parties. She worked to bring the separated groups back together to make the movement stronger. Because of her actions, she became president of the NUWSS. From 1910 to 1912, she supported a bill to give voting rights to single and widowed women who owned households. She believed that by supporting Britain in World War I, women would be recognized as important members of society and deserve basic rights like voting. Millicent Fawcett came from a family of activists. Her sister, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, was the first woman to become a doctor in Britain. Elizabeth was also elected mayor of Aldeburgh in 1908 and gave speeches supporting suffrage.

Emily Davies became an editor of a feminist magazine called Englishwoman's Journal. She shared her feminist ideas through her writing and was a major supporter of women's rights in the 20th century. Besides suffrage, she also pushed for women to have better access to education. She wrote books like Thoughts on Some Questions Relating to Women (1910) and Higher Education for Women (1866). She was a strong voice when organizations were trying to bring about change. Her friend, Barbara Bodichon, also published articles and books like Women and Work (1857) and Enfranchisement of Women (1866).

Mary Gawthorpe was an early suffragette who left her teaching job to fight for women's voting rights. She was put in prison after interrupting Winston Churchill. After her release, she moved to the United States and settled in New York. She worked in the trade union movement and became a full-time official for a clothing workers' union in 1920.

Men Who Supported Women's Vote

Men also played a part in the suffrage movement.

Laurence Housman

Laurence Housman was a male feminist who dedicated himself to the suffrage movement. He mostly contributed through art, creating posters and other materials to help women express themselves, encourage people to join, and share information about suffrage events. He and his sister, Clemence Housman, created a studio called the Suffrage Atelier. This studio provided a space for women to create art for the movement and earn money. Laurence also created works like the Anti-Suffrage Alphabet and wrote for women's newspapers. He encouraged other men to join the movement. For example, he formed the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage with others, hoping to inspire more men to participate.

What Happened Next

Some historians believe that the strong actions of the suffragettes helped by getting a lot of public attention. It also pushed the more moderate groups to organize better.

The Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst Memorial in London was first dedicated to Emmeline Pankhurst in 1930. A plaque for Christabel Pankhurst was added in 1958.

To celebrate 100 years since women got the right to vote, a statue of Millicent Fawcett was put up in Parliament Square, London in 2018. A photo of suffragettes Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst was also colorized and appeared on the front page of The Daily Telegraph on February 6, 2018, to mark the anniversary.

Timeline of Key Events

- 1818: Jeremy Bentham writes about women's voting rights. Some single women could vote in local parish elections.

- 1832: The Great Reform Act stops women from voting in national elections.

- 1851: The Sheffield Female Political Association is founded and asks Parliament for women's suffrage.

- 1865: John Stuart Mill is elected to Parliament, openly supporting women's suffrage.

- 1867: The Second Reform Act expands voting rights for men.

- 1869: The Municipal Franchise Act gives single women who pay taxes the right to vote in local elections.

- 1883: The Conservative Primrose League is formed.

- 1884: The Third Reform Act doubles the number of male voters.

- 1889: The Women's Franchise League is started.

- 1894: The Local Government Act 1894 allows women to vote in local elections and hold some local government roles.

- 1897: The National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) is formed, led by Millicent Fawcett.

- 1903: The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) is formed, led by Emmeline Pankhurst.

- 1904: More active methods begin. Emmeline Pankhurst interrupts a political meeting.

- February 1907: The NUWSS holds the "Mud March", a large outdoor protest with over 3,000 women. In this year, women could vote in and run for elections in major local authorities.

- 1907: The Artists' Suffrage League and the Women's Freedom League are founded.

- 1908: The Actresses' Franchise League and the Women Writers' Suffrage League are founded.

- November 1908: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson becomes the first woman mayor in Britain, in Aldeburgh.

- 1905, 1908, 1913: The WSPU uses different levels of strong actions, from civil disobedience to property damage.

- July 5, 1909: Marion Wallace Dunlop goes on the first hunger strike.

- September 1909: Force-feeding is used on hunger strikers in English prisons.

- February 1910: A "Conciliation Bill" to give women the vote passes a key vote, but Prime Minister H. H. Asquith does not allow more time for it.

- November 1910: Asquith changes the bill to give more men the vote instead of women.

- November 18, 1910: "Black Friday" – a protest where suffragettes faced violence from police and the public.

- April 1913: The Cat and Mouse Act is passed, allowing hunger-striking prisoners to be released and then re-arrested.

- June 4, 1913: Emily Davison steps in front of the King’s horse at The Derby and is killed.

- March 13, 1914: Mary Richardson slashes a painting in the National Gallery to protest the force-feeding of Emmeline Pankhurst.

- August 4, 1914: World War I begins. WSPU activities stop immediately. NUWSS continues peaceful lobbying.

- February 6, 1918: The Representation of the People Act 1918 gives women over 30 who meet certain property rules the right to vote. About 8.4 million women gain the vote.

- November 21, 1918: The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 allows women to be elected to Parliament.

- 1928: Women in England, Wales, and Scotland get the vote on the same terms as men (over 21) due to the Representation of the People Act 1928.

- 1968: A law in Northern Ireland removes property requirements, making all men and women over 18 in the UK eligible to vote equally.

See also

- Feminism in the United Kingdom

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

- Anti-suffragism

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |