Emily Davison facts for kids

Emily Wilding Davison (born 11 October 1872 – died 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette. She bravely fought for women's right to vote in Britain. This was in the early 1900s.

Emily was a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). This group used strong actions to get attention for their cause. She was arrested nine times. She went on hunger strike seven times. She was also force-fed 49 times in prison.

She died after being hit by King George V's horse, Anmer. This happened at the 1913 Derby horse race. She walked onto the track during the race.

Emily grew up in a middle-class family. She studied at Royal Holloway College, London. She also went to St Hugh's College, Oxford. After her studies, she worked as a teacher and a governess.

She joined the WSPU in November 1906. She quickly became an important leader. She was known for her bold actions. Her methods included breaking windows and throwing stones. She also set fire to postboxes. On three occasions, she even hid overnight in the Palace of Westminster. This included the night of the 1911 census.

Her funeral on 14 June 1913 was a huge event. It was organized by the WSPU. About 5,000 suffragettes and their supporters walked with her coffin. Around 50,000 people watched along the route in London. Her coffin was then taken by train to her family's burial place in Morpeth, Northumberland.

Emily Davison was a strong Christian and a dedicated feminist. She believed that socialism could bring good changes to society.

Contents

Her Life and Fight for Votes

Early Life and School

Emily Wilding Davison was born in Greenwich, London. This was on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison and Margaret Caisley. Both were from Morpeth, Northumberland. Charles was 45 and Margaret was 19 when they married in 1868. Emily was their third child.

Her family moved to Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire, when she was a baby. She was taught at home until she was 11. Then her family moved back to London. She went to a day school there. She also spent a year studying in Dunkirk, France.

At 13, she attended Kensington High School. In 1891, she won a scholarship to Royal Holloway College. She planned to study literature. But her father died in early 1893. Her mother could not afford the school fees. So Emily had to stop her studies.

After leaving Holloway, Emily worked as a governess. She lived with the families she worked for. She continued studying in the evenings. She saved enough money to attend St Hugh's College, Oxford. She went for one term to take her final exams. She earned top marks in English. However, she could not officially graduate. At that time, women were not allowed to get degrees from Oxford.

She worked briefly at a church school in Edgbaston from 1895 to 1896. She found it difficult. She then moved to Seabury, a private school in Worthing. She was happier there. In 1898, she left Worthing. She became a private tutor and governess in Northamptonshire. In 1902, she started studying for a degree at the University of London. She graduated in 1908.

Becoming an Activist

Emily Davison joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in November 1906. Emmeline Pankhurst started the WSPU in 1903. The group believed that strong, direct actions were needed. They wanted to achieve their goal of women's right to vote.

Emily joined the WSPU's campaigns. She became a leader and helped organize marches. By 1908 or 1909, she left her teaching job. She worked full-time for the WSPU. She started taking more direct actions. Sylvia Pankhurst, Emmeline's daughter, called her "one of the most daring" activists.

In March 1909, Emily was arrested for the first time. She was part of a group of 21 women. They marched to see the prime minister, H. H. Asquith. The march ended with a clash with police. She was arrested for "assaulting the police." She was sentenced to one month in prison. After her release, she wrote to Votes for Women, the WSPU's newspaper. She said her work for the cause brought her great joy.

In July 1909, Emily was arrested again. She was with fellow suffragettes Mary Leigh and Alice Paul. They interrupted a public meeting held by David Lloyd George. Women were not allowed at this meeting. She was sentenced to two months. She went on hunger strike and was released after five and a half days. She lost a lot of weight and felt very weak.

She was arrested again in September 1909. She threw stones to break windows at a political meeting. This meeting was only open to men. She was sent to Strangeways prison for two months. She went on hunger strike again. She was released after two and a half days. She wrote to The Manchester Guardian to explain her actions. She said it was a warning to the public. She felt it was justified because women were excluded from public meetings.

Emily was arrested again in October 1909. She was about to throw a stone at Sir Walter Runciman. She thought it was Lloyd George's car. A fellow suffragette, Constance Lytton, threw her stone first. Police stopped Emily. She was charged but released. Constance Lytton was imprisoned. Emily used her court appearances to give speeches. Parts of her speeches were printed in newspapers.

Two weeks later, she threw stones at Runciman at a meeting in Radcliffe, Greater Manchester. She was arrested and sentenced to a week of hard labour. She went on hunger strike again. But the government had started force-feeding prisoners. Emily said the experience was "horrible" and "almost indescribable." After being force-fed, she tried to stop it from happening again. She barricaded her cell door. Prison officers broke a window pane. They used a fire hose on her for 15 minutes. The cell filled with water. She was then force-fed again. She was released after eight days.

Emily sued the prison for using the hose. In January 1910, she won 40 shillings in damages.

In April 1910, Emily tried to enter the House of Commons. She wanted to ask Asquith about votes for women. She hid overnight in the heating system. A policeman found her, but she was not charged. That same month, she started working for the WSPU. She also began writing for Votes for Women.

A group of politicians suggested a new law. It would give the vote to a million women who owned property. The WSPU stopped their protests while the law was discussed. But the law failed in November. The government did not allow enough time to debate it.

A group of 300 WSPU women tried to give a petition to Asquith. Police stopped them roughly. The suffragettes called this day Black Friday. Emily was not arrested. But she was very angry about how the women were treated. The next day, she broke windows at the Crown Office in parliament. She was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison. She went on hunger strike again. She was force-fed for eight days before being released.

On the night of the 1911 census, Emily hid in a cupboard. This was in the chapel of the Palace of Westminster. She stayed hidden all night. She wanted to avoid being counted in the census. This was part of a wider protest by suffragettes. A cleaner found her. Emily was arrested but not charged. She was counted in the census twice. Her landlady also listed her at her lodgings.

Emily wrote many letters to newspapers. She wanted to explain the WSPU's views peacefully. She had 12 letters published in The Manchester Guardian. Between 1911 and 1913, she wrote almost 200 letters to over 50 newspapers. Many were published.

In December 1911, Emily started setting fire to postboxes. She was arrested for setting fire to a postbox outside parliament. She admitted to setting fire to two others. She was sentenced to six months in Holloway Prison. She did not go on hunger strike at first. But the authorities force-fed her. They thought her health was getting worse.

In June, she and other suffragettes barricaded their cells. They went on hunger strike. The authorities broke down the doors and force-fed them. After this, Emily made a "desperate protest." She jumped from an inside balcony in the prison. She broke two bones in her back. She also badly injured her head. Even with her injuries, she was force-fed again. She was released ten days early.

Because of this action, Emily felt pain for the rest of her life. The WSPU leaders did not approve of her setting fire to postboxes. This and other actions made her less popular with the group. Sylvia Pankhurst later wrote that the WSPU wanted to stop Emily from acting on her own.

In November 1912, Emily was arrested for the last time. She attacked a minister with a horsewhip. She had mistaken him for Lloyd George. She was sentenced to ten days in prison. She was released early after a four-day hunger strike. This was her seventh hunger strike. She had been force-fed 49 times.

Her Death at the Derby

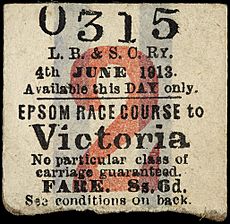

On 4 June 1913, Emily got two flags from the WSPU office. They had the suffragette colours of purple, white, and green. She then traveled by train to Epsom, Surrey. She went to attend the Derby horse race.

She stood in the infield at Tattenham Corner. This was the final bend before the finish line. When some horses had passed her, she went under the guard rail. She ran onto the course. She may have held one of the suffragette flags.

She reached for the reins of Anmer. This was King George V's horse. Herbert Jones was riding it. Anmer was going about 35 miles (56 km) per hour. Emily was hit by the horse. This happened four seconds after she stepped onto the course.

Anmer fell in the collision. The horse partly rolled over its jockey. Emily was knocked to the ground and became unconscious. Some reports say Anmer kicked her in the head. But the surgeon who treated her said he found no sign of a kick. Three newsreel cameras filmed the event.

People rushed onto the track to help Emily and the jockey. Both were taken to Epsom Cottage Hospital. Emily had surgery two days later. But she never woke up. She died on 8 June, at age 40. She died from a fracture at the base of her skull.

The jockey, Herbert Jones, had a concussion and other injuries. He recovered enough to race Anmer two weeks later. He remembered little of what happened. He said, "She seemed to clutch at my horse, and I felt it strike her."

It is not clear why Emily went onto the track. She did not tell anyone her plans. She also did not leave a note. Many ideas have been suggested. Maybe she thought all horses had passed. Or she wanted to pull down the King's horse. Perhaps she wanted to attach a WSPU flag to a horse. Or she intended to throw herself in front of a horse. Historians say there are many theories and guesses about her actions.

In 2013, a TV show used experts to study the old film of the event. They cleaned and examined the film digitally. Their study suggests Emily wanted to throw a suffragette flag around a horse's neck. Or she wanted to attach it to the horse's bridle. A flag was found on the course. It is now displayed in the Houses of Parliament. However, some people question if this is the real flag.

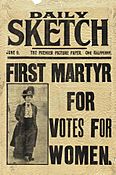

The WSPU quickly called Emily a "martyr." They wanted to show she died for their cause. The Suffragette newspaper showed a female angel on its front page. The paper said Emily proved people would die for an ideal. They used religious words to describe her act.

Her Funeral

On 14 June 1913, Emily's body was moved from Epsom to London. Her coffin had the words "Fight on. God will give the victory." written on it. Five thousand women formed a procession. Hundreds of male supporters followed. They took the coffin between Victoria and Kings Cross stations.

The procession stopped for a short service. The women marched in rows. They wore the suffragette colours of white and purple. A newspaper described it as looking like a military funeral. About 50,000 people watched along the route. This event was a major public display by the suffragettes.

The coffin was then taken by train to Newcastle upon Tyne. Suffragettes guarded it during the journey. Crowds met the train at every stop. The coffin stayed overnight at the city's station. Then it was taken to Morpeth. A procession of about a hundred suffragettes walked with the coffin. They went from the station to the church. Thousands watched them. Only a few suffragettes went into the churchyard. The service and burial were private. Her gravestone has the WSPU slogan: "Deeds not words."

How She is Remembered

Emily Davison's story has been told in many ways. A play called Emily was staged in 1968. An opera about her, also called Emily, was created in 2013. The American rock singer Greg Kihn wrote a song called "Emily Davison."

She also appears in the 2015 film Suffragette. In the film, her death and funeral are a key part of the story. In 2018, a musical piece called Pearl of Freedom told her story.

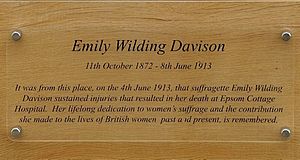

In 1990, politicians Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn placed a plaque. It was inside the cupboard where Emily had hidden in parliament. In April 2013, a plaque was put up at Epsom Downs Racecourse. This marked 100 years since her death.

In 2017, Royal Holloway College named its new library after her. The statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, was unveiled in 2018. It includes Emily Davison's name and picture. This honors her and 58 other women who supported women's suffrage.

The Women's Library in London has many items related to Emily. These include her personal papers and objects from her death. In 2021, a statue of Emily was put in the marketplace at Epsom. This was after a campaign by volunteers. In 2023, English Heritage announced a blue plaque would be put on a house in Kensington, London. She lived there when she attended Kensington High School.

See also

In Spanish: Emily Davison para niños

In Spanish: Emily Davison para niños

- List of suffragists and suffragettes

- Timeline of women's suffrage

- Women's suffrage organisations

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |