Elizabeth Garrett Anderson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

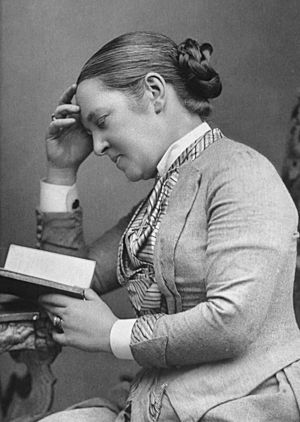

Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

|

|

|---|---|

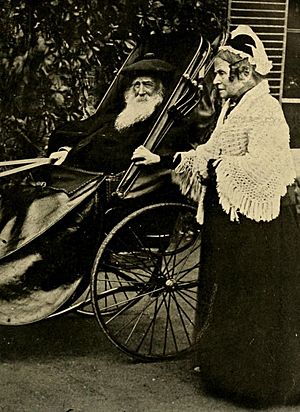

Detail from a portrait of Garrett Anderson circa 1900

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Garrett

9 June 1836 Whitechapel, Commercial Road, London, England

|

| Died | 17 December 1917 (aged 81) Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England

|

| Education | Studied privately with physicians in London hospitals Society of Apothecaries |

| Known for | First woman to gain a medical qualification in Britain Creating a medical school for women |

| Relatives | Louisa Garrett Anderson (daughter) Alan Garrett Anderson (son) Newson Garrett (father) Agnes Garrett (sister) Millicent Garrett Fawcett (sister) |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | Physician |

| Institutions | New Hospital for Women London School of Medicine for Women |

Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (born June 9, 1836 – died December 17, 1917) was an English doctor and a supporter of women's rights. She made history by becoming the first woman in Britain to officially qualify as a doctor and surgeon. She also helped start the first hospital run by women. Elizabeth was the first female dean of a British medical school and the first woman in Britain to be elected to a school board. Later, she became the first female mayor in Britain, serving in Aldeburgh.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Elizabeth was born in Whitechapel, London. She was the second of eleven children. Her father, Newson Garrett, was from Suffolk, and her mother, Louisa, was from London.

Newson Garrett was a determined businessman. He moved his family to Suffolk in 1841. There, he bought a business that sold barley and coal. He built Snape Maltings, which were large buildings used for preparing barley.

The Garrett family lived in Aldeburgh. As Newson's business grew, the family became very successful. In 1850, he built a large house called Alde House. Elizabeth grew up in a time of great change and success. Unlike many girls then, she was encouraged to be interested in local politics. She was also allowed to explore the town, including the salt-marshes, beach, and port.

Education and Dreams

Elizabeth first learned to read, write, and do arithmetic from her mother. When she was 10, a governess, Miss Edgeworth, was hired to teach Elizabeth and her sister. Elizabeth did not enjoy her governess and often tried to outsmart her.

At age 13, Elizabeth and her sister were sent to a private boarding school in London. They studied English literature, French, Italian, and German. Elizabeth later said her teachers were not very good. She wished the school had taught more science and math. However, her time there did help her love reading.

After school, Elizabeth spent nine years at home. But she continued to study Latin and arithmetic. She also read many books. She would give "Talks on Things in General" to her younger siblings, discussing politics and current events.

In 1854, Elizabeth met Emily Davies, who would become a lifelong friend. Emily was a feminist who later helped found Girton College, a college for women. Elizabeth also learned about Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female doctor in the United States. When Blackwell visited London in 1859, Elizabeth met her. This meeting inspired Elizabeth even more.

Around 1860, Elizabeth, Emily Davies, and Elizabeth's younger sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, decided on their life goals. Elizabeth would open the medical profession to women. Emily would open universities to women. Millicent would work for women's right to vote. At first, Elizabeth's father was against her becoming a doctor. But he eventually agreed to support her fully.

Becoming a Doctor

Elizabeth decided to start her medical journey in August 1860. She spent six months as a nurse at Middlesex Hospital in London. She proved to be a good nurse and was allowed to attend clinics and even watch an operation. She tried to join the hospital's medical school but was not allowed. However, she could take private lessons in Latin, Greek, and medicine from the hospital's apothecary. She also hired a tutor to study anatomy and physiology.

Slowly, Elizabeth was allowed into the dissecting room and chemistry lectures. But the male students did not like her presence. In 1861, they complained, and she had to leave the hospital. Still, she left with honors in chemistry and medicine.

Elizabeth then applied to many medical schools across Britain, including Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh. All of them refused to admit her because she was a woman.

She found a way through a loophole in the rules of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. This group could not legally stop her from taking their exam because of her gender. In 1862, she was admitted to study with them. She was the only woman taking the exam that year.

In 1865, Elizabeth finally took her exam and earned her license (LSA) to practice medicine. She was the first woman in Britain to openly become a qualified doctor. (Before her, there was Dr. James Barry, who was born female but lived as a man to practice medicine.) Elizabeth passed with the highest marks.

Right after she qualified, the Society of Apothecaries changed its rules. They made it impossible for other women, like Sophia Jex-Blake, to follow the same path. It wasn't until 1876 that a new law, the Medical Act, allowed all qualified people to get a medical license, no matter their gender.

A Pioneering Career

Even with her license, Elizabeth could not get a job at any hospital because she was a woman. So, in late 1865, she opened her own medical practice in London. At first, she had few patients, but her practice slowly grew.

She wanted to open a clinic for poor women. This would allow them to get medical help from a qualified female doctor. In 1866, she opened St. Mary's Dispensary for Women and Children. In its first year, she treated 3,000 new patients.

Elizabeth also learned that the University of Sorbonne in Paris was open to women medical students. She studied French and earned her medical degree from there in 1870.

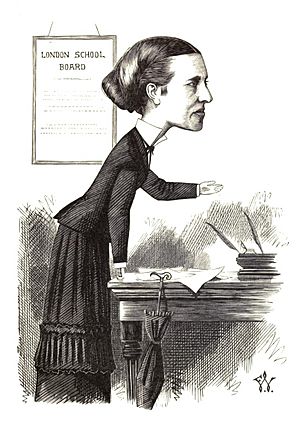

In the same year, she was elected to the first London School Board. She received the most votes of all candidates. She also became a visiting doctor at the East London Hospital for Children. This made her the first woman in Britain to be appointed to a medical hospital job. However, she found it hard to balance these roles with her private practice, the dispensary, and being a new mother. So, she resigned from these posts by 1873.

In 1872, her dispensary became the New Hospital for Women and Children. It treated women from all over London. In 1874, she helped start the London School of Medicine for Women. This was the only teaching hospital in Britain that offered medical courses for women. She worked there for the rest of her career and was the dean from 1883 to 1902. This school later became part of University College London.

British Medical Association

In 1873, Elizabeth became a member of the British Medical Association (BMA). This was a big step, as it was an all-male group. After she and another woman, Frances Hoggan, joined, some members tried to stop women from joining in the future. But others, like Dr. Norman Kerr, argued for equal rights. Elizabeth was often the first woman to break into male-only medical groups. In 1892, women were allowed to join the BMA again. In 1897, Elizabeth was elected president of the East Anglian branch of the BMA.

Elizabeth worked hard to develop the New Hospital for Women and the London School of Medicine for Women. Both institutions were well-equipped. The hospital was run entirely by female doctors. The medical school had over 200 students, mostly women, preparing for medical degrees.

Women's Right to Vote

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson also worked for women's right to vote. In 1866, she and Emily Davies presented petitions with over 1,500 signatures, asking for women who owned homes to be allowed to vote. Elizabeth joined the first British Women's Suffrage Committee that year.

She was not as active as her sister, Millicent Garrett Fawcett, who became a leader in the movement. But Elizabeth did become a member of the Central Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage in 1889. After her husband died in 1907, she became more involved. As mayor of Aldeburgh, she gave speeches supporting women's right to vote. However, she stepped back in 1911 as the movement became more aggressive. Her daughter, Louisa Garrett Anderson, also a doctor, was more active and even spent time in prison for her suffrage work.

Personal Life

In 1871, Elizabeth married James George Skelton Anderson. She continued her medical practice after marriage. They had three children: Louisa (who also became a doctor), Margaret (who died young), and Alan.

Elizabeth and James retired to Aldeburgh in 1902. James died in 1907. Elizabeth enjoyed her marriage and later spent time gardening and traveling with her family.

On November 9, 1908, she was elected mayor of Aldeburgh. She was the first female mayor in England. Her father had also been mayor in 1889.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson died in 1917 and is buried in the churchyard of St Peter and St Paul's Church, Aldeburgh.

Legacy

The New Hospital for Women was renamed the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital in 1918. Today, it is part of the University College Hospital Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Wing.

The old hospital buildings are now the national headquarters for the trade union UNISON. The Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Gallery inside tells the story of Elizabeth, her hospital, and women's fight for equality in medicine.

The critical care center at Ipswich Hospital is named the Garrett Anderson Centre in her honor. The new medical school at the University of Worcester will be called the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Building.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson School, a secondary school for girls in London, is also named after her.

Her historical papers are kept at the Women's Library in London.

On June 9, 2016, Google Doodle celebrated her 180th birthday. The NHS Leadership Academy also has a master's degree program in leadership and management named after her.

Images for kids

-

Garrett Anderson with Emmeline Pankhurst on Black Friday, November 18, 1910.

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Garrett Anderson para niños