Elizabeth Blackwell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Blackwell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 3 February 1821 Bristol, England

|

| Died | 31 May 1910 (aged 89) Hastings, England

|

| Nationality | British and American |

| Education | Geneva Medical College |

| Occupation |

|

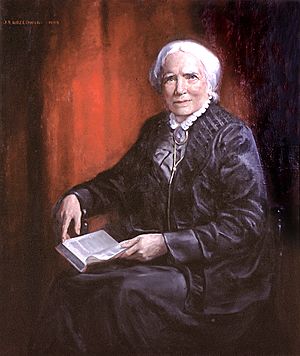

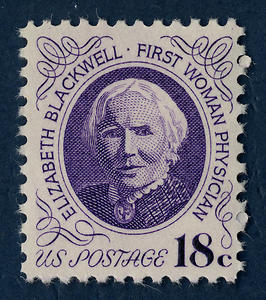

Elizabeth Blackwell (born February 3, 1821 – died May 31, 1910) was a British and American doctor. She made history as the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. She was also the first woman to be listed on the Medical Register in the United Kingdom.

Elizabeth Blackwell was a social reformer in both the US and the UK. She was a leader in helping women get an education in medicine. Today, the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal is given each year to a woman who has greatly helped women in medicine.

Blackwell didn't plan to become a doctor at first. She became a schoolteacher to help her family. This was a common job for women in the 1800s. But she soon found it wasn't for her. Her interest in medicine began when a friend got sick. Her friend said she might not have suffered so much if a female doctor had cared for her.

Blackwell started applying to medical schools. Right away, she faced unfair treatment because she was a woman. She was turned down by every medical school she applied to. Only Geneva Medical College in New York accepted her. The male students there voted for her to join. So, in 1847, Blackwell became the first woman to attend medical school in the United States.

Her first medical paper was about typhoid fever. It was published in 1849, soon after she graduated. This was the first medical article published by a female student in the US. It showed her strong sense of caring for others. She also wrote about the need for fairness in society. Doctors at the time thought this caring view was "feminine."

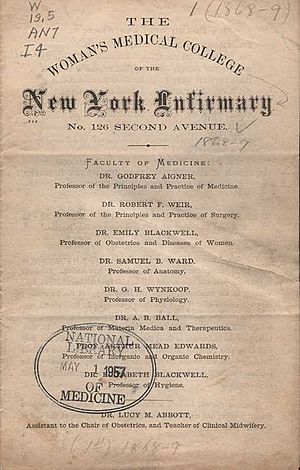

In 1857, Blackwell and her sister Emily Blackwell started the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Elizabeth also gave talks to women about why it was important for girls to get an education. She helped a lot during the American Civil War by organizing nurses. The Infirmary also started a medical school for women. This gave women important hands-on training with patients. Later, she went back to England. In 1874, she helped create the London School of Medicine for Women.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Elizabeth was born on February 3, 1821, in Bristol, England. Her father, Samuel Blackwell, was a sugar refiner. Her mother was Hannah (Lane) Blackwell. Elizabeth had two older sisters, Anna and Marian. She later had six younger siblings: Samuel, Henry, Emily, Sarah Ellen, John, and George. Her sister Emily also became a doctor, the second woman in the US to do so. Four of her aunts also lived with the family.

In 1832, her family moved from Bristol, England, to New York. This was because Samuel Blackwell lost his sugar refinery in a fire. In New York, Elizabeth's father became active in the movement to end slavery. So, family dinners often included talks about women's rights, slavery, and child labor.

Her parents, Hannah and Samuel, had modern ideas about raising children. For example, instead of hitting their children for bad behavior, they wrote down their mistakes in a "black book." If too many mistakes built up, the children had to eat dinner alone in the attic.

Samuel Blackwell also had modern views on education. He believed that every child, including his daughters, should be able to develop their talents fully. This was a rare idea at the time. Most people thought women should only be homemakers or schoolteachers. Elizabeth had a governess and private tutors. Because of this, she mostly spent time with her family as she grew up.

A few years later, the family moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. When Elizabeth was 17, her father died. This left the family with very little money.

Becoming an Adult

The Blackwell family faced money problems. So, Elizabeth and her sisters Anna and Marian started a school. It was called The Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies. They taught many subjects and charged for lessons and for students to live there. The school was mainly a way for the sisters to earn money. During these years, Elizabeth's work against slavery took a backseat.

In 1838, Blackwell joined the Episcopal Church. But in 1839, a Unitarian minister named William Henry Channing came to Cincinnati. He introduced Elizabeth to new ideas about thinking and self-improvement. She started going to the Unitarian Church. This caused problems with the community in Cincinnati. As a result, the academy lost many students and closed in 1842. Blackwell then began teaching private students.

Channing's arrival made Blackwell interested in education and reform again. She worked on improving her own mind. She studied art, went to lectures, wrote stories, and attended different church services. In the early 1840s, she started writing about women's rights in her diaries and letters.

In 1844, her sister Anna helped Blackwell get a teaching job in Henderson, Kentucky. The job paid well. But she found the living conditions and schoolhouse poor. What bothered her most was seeing slavery up close for the first time. She said, "Kind as the people were to me personally, the sense of justice was continually outraged." She quit after six months. She returned to Cincinnati, determined to find a more meaningful way to live her life.

Education and Medical Training

Elizabeth's sister Anna helped her again. Blackwell got a job teaching music at a school in Asheville, North Carolina. Her goal was to save $3,000 for medical school. In Asheville, Blackwell stayed with Reverend John Dickson. He had been a doctor before becoming a clergyman. Dickson supported Blackwell's dream. He let her use the medical books in his library to study. During this time, Blackwell found comfort in religious thought. She also renewed her interest in fighting slavery. She started a Sunday school for enslaved people, but it didn't last.

Dickson's school soon closed. Blackwell then moved to the home of Reverend Dickson's brother, Samuel Henry Dickson. He was a well-known doctor in Charleston, South Carolina. In 1846, she started teaching at a boarding school in Charleston. With the help of Reverend Dickson's brother, Blackwell wrote letters asking about medical study. She received no positive replies. In 1847, Blackwell left Charleston for Philadelphia and New York. She wanted to look for medical study opportunities in person. Blackwell really wanted to be accepted into one of the medical schools in Philadelphia.

She wrote about her strong determination:

My mind is fully made up. I have not the slightest hesitation on the subject; the thorough study of medicine, I am quite resolved to go through with. The horrors and disgusts I have no doubt of vanquishing. I have overcome stronger distastes than any that now remain, and feel fully equal to the contest. As to the opinion of people, I don't care one straw personally; though I take so much pains, as a matter of policy, to propitiate it, and shall always strive to do so; for I see continually how the highest good is eclipsed by the violent or disagreeable forms which contain it.

When she arrived in Philadelphia, Blackwell stayed with Dr. William Elder. She studied anatomy privately with Dr. Jonathan M. Allen. She tried to get into any medical school in Philadelphia. But she faced resistance almost everywhere. Most doctors told her to go to Paris to study. Some even suggested she pretend to be a man to study medicine. The main reasons for her rejection were that she was a woman and thought to be less intelligent. Also, they worried she might be good enough to compete with them. They didn't want to "furnish [her] with a stick to break our heads with." Out of desperation, she applied to twelve smaller "country schools."

Medical School in the United States

In October 1847, Geneva Medical College in Geneva, New York, accepted Blackwell as a medical student. The dean and professors usually decided who to accept. But they couldn't decide on Blackwell's special case. They let the 150 male students vote. The rule was that if even one student objected, Blackwell would be turned away. The young men voted unanimously to accept her.

When Blackwell arrived at the college, she was nervous. Everything was new to her. But she soon felt at home in medical school. The townspeople of Geneva saw her as unusual. She also avoided potential partners and friends. She preferred to be alone. In the summer between her two terms, she went back to Philadelphia. She stayed with Dr. Elder and looked for medical jobs to gain experience. The city group that ran Blockley Almshouse allowed her to work there, but it was a struggle. Blackwell slowly gained acceptance at Blockley. Still, some young male doctors would walk out and refuse to help her treat patients. During her time there, Blackwell gained valuable hands-on experience. Her graduation paper at Geneva Medical College was about typhus. This paper connected physical health with social well-being. This idea hinted at her later work for social change.

On January 23, 1849, Blackwell became the first woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. Local newspapers reported her graduation positively. When the dean, Dr. Charles Lee, gave her degree, he stood up and bowed to her.

Medical Studies in Europe

In April 1849, Blackwell decided to continue her studies in Europe. She visited a few hospitals in Britain. Then she went to Paris. Her experience there was similar to America. Many hospitals rejected her because she was a woman. In June, Blackwell joined La Maternité, a hospital for mothers. She was accepted as a student midwife, not a doctor. She met Hippolyte Blot, a young doctor there. She gained much medical experience from his teaching. By the end of the year, Paul Dubois, a leading expert in childbirth, said she would be the best obstetrician in the United States, male or female.

On November 4, 1849, Blackwell was treating a baby with an eye infection. She accidentally squirted some infected fluid into her own eye. She caught the infection and lost sight in her left eye. This meant she could no longer hope to become a surgeon. After recovering, she enrolled at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London in 1850. She regularly attended lectures by James Paget. She made a good impression there. But she still faced problems when she tried to observe patients in the wards.

Blackwell felt that the unfair treatment against women in medicine was not as strong in Europe. So, she returned to New York City in 1851. She hoped to start her own medical practice.

Medical Career

Medical Work in the United States

Blackwell did get some support from the media. In 1852, she started giving lectures. She also published her first book, The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls. This book was about how girls develop physically and mentally. It also talked about preparing young women for motherhood.

In 1853, Blackwell opened a small clinic near Tompkins Square Park. She also took Marie Elizabeth Zakrzewska, a Polish woman studying medicine, under her wing. Blackwell helped her with her pre-medical studies. In 1857, Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, along with Elizabeth and her sister Emily, expanded Blackwell's clinic. It became the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. Women served on the board, on the executive committee, and as doctors. The hospital treated both inpatients and outpatients. It also trained nurses. The number of patients doubled in its second year.

Civil War Efforts

When the American Civil War began, the Blackwell sisters helped with nursing efforts. Elizabeth strongly supported the North because of her beliefs against slavery. She even said she would have left the country if the North had given in on slavery. However, Blackwell faced some resistance from the male-led United States Sanitary Commission (USSC). The male doctors refused to help with the nurse training plan if the Blackwells were involved.

In response, Blackwell organized with the Woman's Central Relief Association (WCRA). The WCRA tried to fix the problem of unorganized charity work. But it was eventually taken over by the USSC. Still, the New York Infirmary worked with Dorothea Dix to train nurses for the Union army.

Medical Career at Home and Abroad

Blackwell made several trips back to Britain. She wanted to raise money and try to start a similar hospital project there. In 1858, she was able to become the first woman listed on the General Medical Council's medical register. This was thanks to a rule in the Medical Act 1858 that recognized doctors with foreign degrees who practiced in Britain before 1858. She also became a mentor to Elizabeth Garrett Anderson at this time. By 1866, nearly 7,000 patients were being treated each year at the New York Infirmary. Blackwell was needed back in the United States.

The parallel project in Britain didn't happen. But in 1868, a medical college for women was started next to the infirmary. It included Blackwell's new ideas about medical education. This meant a four-year training period with much more hands-on clinical training than before.

At this point, a disagreement grew between Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell. Both were very strong-willed. A power struggle over how to run the infirmary and medical college began. Elizabeth felt a bit left out by the women's medical movement in the United States. So, she left for Britain to try to establish medical education for women there. In July 1869, she sailed for Britain.

In 1874, Blackwell started a women's medical school in London with Sophia Jex-Blake. Jex-Blake had been a student at the New York Infirmary years earlier. Blackwell had doubts about Jex-Blake. She thought Jex-Blake was difficult and lacked tact. Still, Blackwell became deeply involved with the school. It opened in 1874 as the London School of Medicine for Women. Its main goal was to prepare women for the licensing exam. Blackwell strongly disagreed with using vivisections (experiments on live animals) in the school's lab.

After the school was established, Blackwell lost much of her power to Jex-Blake. She was elected as a lecturer in childbirth. She quit this job in 1877, officially retiring from her medical career.

Blackwell saw medicine as a way to improve society and morals. But her student Mary Putnam Jacobi focused on curing diseases. Blackwell believed women would succeed in medicine because of their caring female values. But Jacobi thought women should participate as equals to men in all medical fields.

Time in Europe – Social Reform

After moving to Britain in 1869, Blackwell became interested in many different things. She was active in social reform and writing. In 1871, she helped start the National Health Society. She saw herself as a wealthy woman who had time for reform and intellectual activities. Her money from investments in America supported her. She cared about her social standing. Her friend, Barbara Bodichon, helped her meet important people. She traveled across Europe many times during these years.

Her most active period for reform was after she retired from medicine, from 1880 to 1895. Blackwell was interested in many reform movements. These included moral reform, hygiene, and medical education. She also cared about preventing illness, sanitation, family planning, women's rights, and animal rights. She moved between many different reform organizations. She tried to keep a position of power in each. Blackwell had a big, hard-to-reach goal: perfect moral behavior. All her reform work followed this idea. She even helped start two ideal communities in the 1880s.

She believed that Christian morals should be as important as science in medicine. She thought medical schools should teach this basic truth. She also didn't believe in vivisections. She didn't see the value of inoculation and thought it was dangerous. She believed that bacteria were not the only important cause of disease. She felt their importance was being overstated.

Personal Life

Friends and Family

Blackwell had many connections in both the United States and the United Kingdom. She wrote letters to Anne Isabella Byron, Baroness Byron about women's rights. She became very close friends with Florence Nightingale. They talked about opening and running a hospital together. She remained lifelong friends with Barbara Bodichon. She also met Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1883. She was close with her family and visited her siblings whenever she could.

However, Blackwell had a very strong personality. She was often critical of others, especially other women. Blackwell had a falling out with Florence Nightingale. Nightingale wanted Blackwell to focus on training nurses. She didn't think training female doctors was important. After that, Blackwell's comments on Florence Nightingale's writings were often very critical. She was also critical of many women's reform and hospital groups where she had no role. She called some of them "quack auspices." Blackwell also didn't get along well with her stubborn sisters Anna and Emily. She also had issues with the women doctors she mentored after they became established. Among women, Blackwell was very assertive. She found it hard to play a less important role.

Kitty Barry

In 1856, while setting up the New York Infirmary, Blackwell adopted Katherine "Kitty" Barry (1848–1936). Kitty was an Irish orphan from the New York House of Refuge. Blackwell's diary entries show she adopted Barry partly out of loneliness and duty. She also needed help around the house. Barry was raised as both a helper and a daughter.

Blackwell did provide for Barry's education. She even taught Barry gymnastics to test her ideas from her book, The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls. However, Blackwell never let Barry develop her own interests. She didn't try to introduce Barry to young people her own age. Barry herself was shy and a bit self-conscious because she was slightly deaf. Barry followed Blackwell during her many moves across the Atlantic. She also moved with Blackwell during her house hunt between 1874 and 1875, when they moved six times. Finally, they moved to Blackwell's last home, Rock House, in Hastings, Sussex, in 1879.

Barry stayed with Blackwell her entire life. After Blackwell's death, Barry stayed at Rock House. Then she moved to Kilmun in Argyllshire, Scotland. Blackwell was buried in the churchyard of St Munn's Parish Church there. In 1920, Barry moved in with other Blackwell family members and took the Blackwell name. On her deathbed in 1936, Barry called Blackwell her "true love." She asked for her ashes to be buried with Elizabeth's.

Private Life

None of the five Blackwell sisters ever married. Elizabeth thought dating was foolish early in her life. She valued her independence. Even during her time at Geneva Medical College, she turned down offers from a few suitors.

Later Years and Death

In her later years, Blackwell was still quite active. In 1895, she published her autobiography, Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. It was not very successful, selling fewer than 500 copies. After this book, Blackwell slowly stepped back from public reform work. She spent more time traveling. She visited the United States in 1906 and took her first and last car ride. Blackwell's old age began to limit her activities.

In 1907, while on holiday in Kilmun, Scotland, Blackwell fell down a flight of stairs. This left her almost completely mentally and physically disabled. On May 31, 1910, she died at her home in Hastings, Sussex. She had suffered a stroke that paralyzed half her body. Her ashes were buried in the graveyard of St Munn's Parish Church, Kilmun. Newspapers like The Lancet and The British Medical Journal published tributes honoring her.

Legacy and Influence

The British artist Edith Holden was given the middle name "Blackwell" in Elizabeth's honor. Edith's Unitarian family were relatives of Blackwell.

Influence on Medicine

After Blackwell graduated in 1849, her paper on typhoid fever was published in the Buffalo Medical Journal and Monthly Review.

In 1857, Blackwell opened the New York Infirmary for Women with her younger sister Emily. At the same time, she gave lectures to women in the United States and England. She spoke about the importance of educating women and the medical profession for women. In the audience at one of her lectures in England was Elizabeth Garrett Anderson. She later became the first woman doctor in England in 1865.

In 1874, Blackwell worked with Florence Nightingale, Sophia Jex-Blake, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Emily Blackwell, and Thomas Henry Huxley. They created the first medical school for women in England, the London School of Medicine for Women. Blackwell served as the Chair of Hygiene there.

Blackwell settled in England in the 1870s. She continued to work on expanding the medical profession for women. She influenced as many as 476 women to become registered medical professionals in England alone. Until her death, Blackwell worked in a busy practice in Hastings, England. She also continued to lecture at the School of Medicine for Women.

Honors and Recognition

Two institutions honor Elizabeth Blackwell as a former student:

- Hobart and William Smith Colleges, which is the current name of Geneva College, the original school of Geneva Medical College.

- The State University of New York Upstate Medical University, which took over Geneva Medical College in 1871.

Since 1949, the American Medical Women's Association has given the Elizabeth Blackwell Medal each year to a female doctor. Hobart and William Smith Colleges also gives an annual Elizabeth Blackwell Award. This award goes to women who have shown "outstanding service to humankind."

In 1973, Elizabeth Blackwell was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame.

The famous artwork The Dinner Party includes a place setting for Elizabeth Blackwell.

In 2013, the University of Bristol launched the Elizabeth Blackwell Institute for Health Research.

On February 3, 2016, National Women Physicians Day was declared a National Holiday. This was championed by Physician Moms Group. They published a study showing that most women doctors still face discrimination because of their gender or being a mother. The holiday honors Dr. Blackwell's role in influencing women doctors today and their fight for fairness.

On February 3, 2018, Google honored her with a Google Doodle for her 197th birthday.

In May 2018, a special plaque was put up at the old location of the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister Emily Blackwell founded this infirmary. For the event, a jewelry designer created a Blackwell Collection of jewelry inspired by Elizabeth Blackwell.

Hobart and William Smith Colleges built a statue on their campus honoring Blackwell.

A 2021 book by Janice P. Nimura, The Doctors Blackwell, tells the life story of Elizabeth Blackwell and her sister Emily Blackwell.

Selected Writings

- 1849 The Causes and Treatment of Typhus, or Shipfever (her medical thesis)

- 1852 The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls (a booklet based on her lectures)

- 1856 An appeal in behalf of the medical education of women

- 1860 Medicine as a Profession for Women (a lecture)

- 1864 Address on the Medical Education of Women

- 1881 "Medicine and Morality" (published in Modern Review)

- 1887 Purchase of Women: the Great Economic Blunder

- 1871 The Religion of Health (lectures)

- 1883 Wrong and Right Methods of Dealing with Social Evil, as shown by English Parliamentary Evidence

- 1888 On the Decay of Municipal Representative Government – A Chapter of Personal Experience

- 1890 The Influence of Women in the Profession of Medicine

- 1891 Erroneous Method in Medical Education etc.

- 1892 Why Hygienic Congresses Fail

- 1895 Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women – Autobiographical Sketches (her autobiography)

- 1898 Scientific Method in Biology

- 1902 Essays in Medical Sociology, 2 vols

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Blackwell para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Blackwell para niños

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, first woman to get a medical qualification in Britain

- James Barry, possibly the first female-bodied doctor (assigned female at birth but lived as a man)

- List of first female physicians by country

- Rebecca Lee Crumpler, first African American female doctor

- State University of New York Upstate Medical University