O. G. S. Crawford facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

O. G. S. Crawford

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford

28 October 1886 Breach Candy, Bombay, British India

|

| Died | 28 November 1957 (aged 71) Nursling, Hampshire, England, United Kingdom

|

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Archaeologist |

| Known for | Aerial photography pioneer |

Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford (born October 28, 1886 – died November 28, 1957) was a British archaeologist. He specialized in studying the ancient history of prehistoric Britain and Sudan. Crawford was a big supporter of aerial archaeology, which means finding old sites from the air. He spent most of his career as the main archaeologist for the Ordnance Survey (OS), a group that makes maps. He also wrote many books about archaeology.

Crawford was born in Bombay, British India, to a wealthy Scottish family. He moved to England as a baby and was raised by his aunts. He studied geography at Keble College, Oxford. After a short time working in geography, he decided to focus on archaeology. He worked for a rich helper named Henry Wellcome, overseeing an archaeological dig in Sudan. He returned to England just before the First World War.

During the war, he served in the army and the air force. He helped with looking at the ground and taking photos from planes along the Western Front. After an injury, he was captured by the German Army in 1918. He was a prisoner of war until the war ended.

In 1920, Crawford joined the Ordnance Survey. He traveled around Britain to map archaeological sites. He found many new ones. He became very interested in aerial archaeology. He used Royal Air Force photos to find the full length of the Stonehenge Avenue. He even dug there in 1923. With archaeologist Alexander Keiller, he flew over southern England to survey sites. They also helped raise money to protect the land around Stonehenge.

In 1927, he started a famous archaeology magazine called Antiquity. Many important British archaeologists wrote for it. He was also president of The Prehistoric Society in 1939. During the Second World War, he photographed buildings in Southampton that were at risk from bombing. After retiring in 1946, he focused again on Sudanese archaeology. He wrote more books before he passed away.

Friends and colleagues remembered Crawford as someone who could be grumpy. However, his work in British archaeology, especially with Antiquity and aerial archaeology, is highly praised. Some people call him one of the most important pioneers in the field. His collection of photographs is still useful to archaeologists today.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Discovering Archaeology: 1886–1904

O. G. S. Crawford was born on October 28, 1886. His birthplace was Breach Candy, a part of Bombay in British India. His father, Charles Edward Gordon Crawford, was a government worker and a judge. Crawford's mother, Alice Luscombe Mackenzie, died soon after he was born. When he was three months old, he was sent to England. His aunt, an Anglican nun, took care of him on the journey.

In Britain, he lived with two other aunts in central London for seven years. They were very religious. Crawford saw his father only a few times before his father died in India in 1894. In 1895, Crawford and his aunts moved to a country house in East Woodhay, Hampshire. He first went to Park House School, which he liked. Then he moved to Marlborough College, where his father had studied. He was unhappy there and complained about bullying.

At Marlborough College, his housemaster, F. B. Malim, helped him. Malim led the archaeology part of the college's Natural History Society. He encouraged Crawford's interest in the subject. Malim might have been like a father figure to young Crawford. With the society, Crawford visited famous archaeological sites. These included Stonehenge, West Kennet Long Barrow, and Avebury.

Through the society, he also got Ordnance Survey maps. These maps helped him explore the hills near his aunts' home. He started digging a barrow (an ancient burial mound). This caught the attention of Harold Peake, an expert in old things. Peake and his wife lived a free-spirited life. They were vegetarians and wanted social change. Their ideas greatly influenced Crawford. Because of them, Crawford stopped being religious. He chose a scientific view of the world instead. Peake taught Crawford to understand past societies by looking at the landscape. This was different from just reading old texts or looking at artifacts.

University Studies and First Jobs: 1905–1914

After school, Crawford won a scholarship to Keble College, Oxford. He started studying classical subjects in 1905. But after getting a low score in his second year, he switched to geography in 1908. In 1910, he earned a special award for his diploma. For this, he studied the land around Andover. He was interested in how geography and archaeology connect.

During a trip to Ireland, he wrote a paper. It was about where Bronze Age axes and beakers were found in Britain and Ireland. This paper was presented to the Oxford University Anthropological Society. It was later published in The Geographical Journal. Another archaeologist, Grahame Clark, later said this paper was a big step in British archaeology. It was the first real attempt to understand ancient events from where archaeological objects were found.

After graduating, Crawford worked as a junior teacher in Oxford's geography department for a year. He then decided to focus on archaeology. But there were not many professional archaeology jobs in Britain then. He applied for jobs elsewhere, but without success.

In 1913, Crawford got a job with an expedition to Easter Island. The goal was to learn about the island's first people and its giant Moai statues. But Crawford argued with the leaders of the expedition. He left the ship and returned to Britain. Then, a rich helper named Henry Wellcome hired him. Wellcome sent him to Egypt to learn more about archaeological digging. After that, Crawford went to Sudan. From January to June 1914, he led the digging of an ancient site called Abu Geili. When he returned to England, he started digging a long barrow in Wiltshire with a friend.

Serving in the First World War: 1914–1918

While Crawford was digging, the United Kingdom entered the First World War. Crawford joined the British Army. He was sent to the Western Front in France. He got sick with the flu and malaria. In February, he was sent back to England to get better.

After recovering, he joined the Royal Flying Corps (RFC). He became an officer in May 1915. In July 1915, he joined the Royal Berkshire Regiment. He used his skills as the regiment's maps officer. He mapped areas near the front line, including German army positions. He also took photos for British propaganda. In 1916, he guided the writer H. G. Wells around the trenches.

In January 1917, Crawford joined 23 Squadron RFC as an observer. He flew over enemy lines to watch and draw maps. On his first flight, his plane was shot at. His right foot was badly injured. He spent time in hospitals in France and England. During this time, he started writing a book called Man and his Past. It looked at human history from an archaeological and geographical view.

In September 1917, Crawford was promoted. He joined 48 Squadron RFC. He again took aerial photos during missions. In February 1918, Crawford's plane was shot down. He and his pilot were taken as prisoners of war. He was first held in Germany. He tried to escape by swimming in a river but was quickly caught. He was then moved to another camp. He spent his time working on his book and reading. Crawford stayed in the camp for seven months. After the war ended, he returned to Britain.

Archaeological Career: 1920–1945

Ordnance Survey and Antiquity Journal

Back in England, Crawford finished Man and his Past. It was published in 1921. This book was like a call to action for a new generation of archaeologists. It suggested that all archaeological topics should be studied using maps.

Crawford also returned to digging. In mid-1920, he dug at Roundwood, Hampshire. His skills led to an invitation from the Ordnance Survey (OS). He was asked to be their first archaeological officer. He accepted and started work in October 1920. His job was to update information about archaeological sites on OS maps. This meant a lot of fieldwork. He traveled across Britain to check old sites and find new ones. He started in Gloucestershire in late 1920. He visited many sites and added many unknown burial mounds to the map. Based on this, he published a book in 1925.

He traveled all over Britain, often by bicycle. He took photos at archaeological sites. He also got aerial photos of sites from the Royal Air Force. In 1921, the Ordnance Survey published his guide for amateur archaeologists. It explained how to find traces of old monuments and roads. He also started making "period maps" that showed archaeological sites. The first one was about Roman Britain, published in 1924. It sold out quickly. He made more maps in the 1930s. His job was made permanent in 1926. By 1938, he had an assistant to help him.

Crawford became very interested in aerial archaeology. He said this new method was as important to archaeology as the telescope was to astronomy. He published two OS leaflets with aerial photos in 1924 and 1929. He strongly promoted aerial archaeology. He collected these photos from RAF files and from other flyers.

Using RAF aerial photos, Crawford figured out the length of the Avenue at Stonehenge. He then dug at the site with A. D. Passmore in late 1923. This project got a lot of press attention. It led to him meeting Alexander Keiller, a rich archaeologist. Keiller invited Crawford to join him on an aerial survey. They flew over several counties in 1924, taking photos of archaeological traces. Many of these photos were published in their book Wessex from the Air in 1928. In 1927, Crawford and Keiller helped raise money to buy the land around Stonehenge. They gave it to The National Trust to protect it.

In 1927, Crawford started Antiquity; A Quarterly Review of Archaeology. This magazine aimed to bring together archaeological research from around the world. Crawford wanted Antiquity to be a rival to other older journals. He thought the Society of Antiquaries did not do enough research on prehistory. Antiquity focused a lot on British archaeology. It featured articles from many young archaeologists who became leaders in the field. They shared Crawford's goal to make archaeology more professional and scientific. Some of these archaeologists called Crawford "Ogs" or "Uncle Ogs."

The journal was very important from the start. It shared news of archaeological discoveries with a wider public. This made it more accessible than other scholarly journals. Crawford received letters from people with unusual ideas about archaeology. He called these "Crankeries." He refused to publish ads for ideas he thought were wrong. In 1938, Crawford was President of the Prehistoric Society. He started new excavations. He invited a German archaeologist, Gerhard Bersu, to England to oversee a dig.

Travels and New Ideas

Crawford loved to travel. In 1928, the OS sent him to the Middle East to collect aerial photos from the First World War. In 1931, he visited Germany and Austria. He bought a new camera there. He later visited Italy to see if OS maps could be made for its archaeological sites. In November 1932, he met the Italian leader Benito Mussolini. Mussolini was interested in Crawford's ideas about mapping archaeological sites in Rome. This was part of a bigger plan to map the entire Roman Empire. Crawford visited many parts of Europe for this project in the late 1920s and 1930s. He also went on holidays to places like Romania, Corsica, and Cyprus. In 1936, he bought land in Cyprus and built a house. During these trips, he visited archaeological sites and met local archaeologists. He encouraged them to write articles for Antiquity.

Crawford believed that society would get better with more international cooperation and science. He became a socialist, influenced by his friend V. Gordon Childe. He thought socialism was the natural next step for science in human affairs. He tried to include Marxist ideas in his archaeological interpretations. He became very excited about the Soviet Union. He saw it as a leader for a future world state.

In May 1932, he traveled to the Soviet Union with a friend. They visited many cities. Crawford admired what he saw as progress in the Soviet Union. He thought it was becoming more equal and that scientists were respected. He wrote about his trip in a book called A Tour of Bolshevy. He said he wrote it to help end capitalism. The book was not published. He joined the Friends of the Soviet Union and wrote for a newspaper. But he never joined the Communist Party. He feared it would risk his job.

In Britain, he photographed sites linked to famous Marxists. He also photographed signs put up by landowners and religious groups. He believed he was documenting capitalist society before socialism would change it. He photographed pro- and anti-fascist propaganda in Britain and Germany. He thought fascism was a temporary part of capitalism. He still admired German archaeology under the Nazi government. He noted that Britain did not fund archaeology as much. He did not comment on the Nazis' political reasons for promoting archaeology.

Despite his socialist views, Crawford believed in working with all foreign archaeologists. This was true no matter their political differences. In early 1938, he gave a talk on aerial archaeology at the German Air Ministry. The Ministry published his talk. Crawford was frustrated that the British government was not as eager to publish his work. He then visited Vienna to meet his friend, archaeologist Oswald Menghin. Menghin took Crawford to an event celebrating the Anschluss. There, he met a famous Nazi, Josef Bürckel. Soon after, he visited Schleswig-Holstein. German archaeologists showed him the Danevirke, an ancient defense wall.

In 1939, Crawford helped photograph the excavation of the Sutton Hoo Anglo-Saxon ship burial in Suffolk. He was there from July 24 to 29, 1939. He took 124 photographs. Many of his photos are used in the British Museum's display of Sutton Hoo artifacts. His photos recorded the digging process and the artifacts found. Taking such a detailed photographic record of an archaeological dig was new at the time.

In the late 1930s, he started a book called Bloody Old Britain. He wanted to use archaeological methods to study modern society. He was very critical of Britain. He looked at 1930s Britain through its everyday objects. He thought it was a society where how things looked was more important than their true value. He blamed this on capitalism and consumerism. The book was not published because of the Second World War. Its unpatriotic nature made it hard to sell.

Second World War Contributions

Before the Second World War, Crawford said he would stay "neutral." He saw the war as a fight between different capitalist powers. After the war began, he decided to destroy his leftist writings if Germany invaded Britain. He feared being punished for having them.

In November 1940, German planes started bombing Southampton. The OS offices were there. Crawford moved some old OS maps to his garage to protect them. He also urged the OS to move their archive to a safe place, but they did not. Later, the OS headquarters were destroyed in the bombing. Most of their archive was lost. Crawford was furious that his warnings were ignored. He found the government's rules and paperwork very frustrating. He tried to find a job abroad but failed.

With little archaeological work at the OS during wartime, Crawford was sent to the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England. His job was to photograph buildings in Southampton for the National Buildings Record. He took pictures of many old buildings and architectural features. These were threatened by the bombing. He took 5,000 photographs during the war. In 1944, the Council for British Archaeology was founded. Crawford was asked to join its first council, but he said no.

Later Life and Legacy: 1946–1957

In 1946, Crawford left his job at the OS as soon as he could. He stayed in the Southampton area. He kept his interest in the city's old buildings, especially those from the Middle Ages. In 1946, he helped start a group called Friends of Old Southampton. This group wanted to protect the city's historic buildings from being destroyed after the war.

After the war, he became very worried about a nuclear war. He urged archaeologists to make copies of all their information. He wanted them to spread these copies to different places. This would ensure that knowledge would survive any future world war. He kept his left-wing interests. But he became disappointed with the Soviet Union. He read books about Joseph Stalin's purges. By 1950, he said he was "fanatically anti-Soviet and anti-communist."

In 1949, Crawford was made a Fellow of the British Academy. In 1950, he became a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire. In 1952, the University of Cambridge gave him an honorary degree. This was for his work in aerial archaeology.

Crawford returned his focus to Sudanese archaeology. He called Sudan "an escape-land of the mind." In 1950, he visited Sudan for an archaeological trip. He wrote a book about the Funj Sultanate of Sennar in northern Sudan. This book came out the same year as his report on the Abu Geili excavation. He also wrote Castles and Churches in the Middle Nile Region in 1953. Another book was Archaeology in the Field (1953), a guide to studying landscapes. In 1955, he published his autobiography, Said and Done. It was described as a lively and funny book that showed his character clearly.

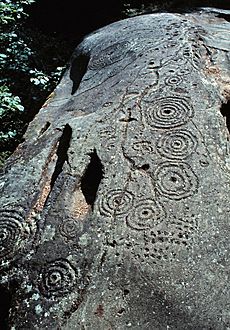

After ancient rock art was found at Stonehenge in 1953, Crawford studied engravings in France. This led him to publish The Eye Goddess in 1957. In this book, he argued that many abstract designs in ancient rock art were eyes. He believed they showed a religion that worshipped a mother goddess. This religion, he thought, existed across the ancient world for a long time. His book was not well received by other academics.

Crawford was also interested in cats. He learned to make cat noises. He even performed them on a BBC radio show called "The Language of Cats." It was very popular. A publisher asked him to write a book about cats, but he never finished it. In the mid-1950s, Crawford became interested in astronomy. He liked the idea of an eternal universe with no beginning or end.

In 1951, a book of essays was published in his honor. It was called Aspects of Archaeology in Britain and Beyond: Essays Presented to O. G. S. Crawford. Many of Crawford's friends worried about him. He lived alone in his cottage with only his housekeeper and cats. He did not have a car or a telephone. He died in his sleep on November 28–29, 1957. He had arranged for some of his letters and books to be destroyed. Others were sent to the Bodleian Library. Some were not to be opened until the year 2000. He was buried in the church graveyard at Nursling. He wanted "Editor of Antiquity" written on his gravestone. This showed he wanted to be remembered mainly as an archaeologist. After Crawford's death, Glyn Daniel became the editor of Antiquity.

Personality

Crawford's socialist beliefs and his dislike of religion were known to his colleagues. He became an atheist while at Marlborough College. He believed strongly in being self-sufficient. He openly disliked people who needed social interaction to be happy. He lived a solitary life, without a family or people who depended on him. It is not known if he had romantic relationships. He loved cats and kept several as pets. He also raised pigs for food and grew vegetables. He was a heavy smoker and rolled his own cigarettes.

Crawford was often irritable. Some colleagues found him difficult to work with. He was known for his impatience. When angry, he would throw his hat to the floor. His biographer, Kitty Hauser, noted that small events would stay with him for decades. He would remember a perceived insult for a long time. However, he could also be friendly and welcoming.

Jonathan Glancey called Crawford a "compelling if decidedly cantankerous anti-hero." Hauser described him as a mix of a snob and a rebel. She also said he was "no great intellectual." Grahame Clark said Crawford's achievements came from his strong moral character. The journalist Neal Ascherson said Crawford was "withdrawn" and "generally ill at ease with other members of the human species."

Glyn Daniel said Crawford had a strong desire to promote archaeology to everyone. He was opinionated and stubborn. He disliked those who saw the past differently from him. Archaeologist Stuart Piggott noted that Crawford could not understand people who studied the past through other subjects, like history. He could not sympathize with anyone not as passionate about ancient field sites as he was. For example, he once called historians "bookish." Archaeologist Jacquetta Hawkes said Crawford's writings in Antiquity showed "righteous indignation" towards many groups.

Mortimer Wheeler, who considered Crawford a close friend, said Crawford was an "outspoken and uncompromising opponent." He added that Crawford had a "boyish glee in calling the bluff of convention." Wheeler also said Crawford had an "inability to work in harness." He would join a committee only to resign quickly. Piggott described Crawford as a mentor. He was encouraging, helpful, and unusual. His strong criticism of the archaeology establishment was exciting to a schoolboy.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Osbert Crawford para niños

In Spanish: Osbert Crawford para niños

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |