Long barrow facts for kids

Long barrows are ancient monuments built in Western Europe about 6,000 to 7,000 years ago, during a time called the Early Neolithic period. These huge structures were made from earth, wood, or stone. The ones made of stone are actually the oldest widespread stone buildings known in the world! Today, we know of about 40,000 long barrows that are still standing.

A long barrow typically looks like a long, low mound of earth, often with ditches on either side. They usually stretch for about 20 to 70 meters (about 65 to 230 feet), though some are much longer or shorter. Some long barrows have a special room or "chamber" inside, made of wood or stone, usually at one end. These chambers often held human remains, which is why archaeologists often think of them as tombs. However, some long barrows don't seem to have been used for burials. Whether they used wood or stone probably depended on what materials were available nearby. Barrows with chambers are called chambered long barrows, and those without are called unchambered long barrows or earthen long barrows.

The very first long barrows appeared in areas like Spain and western France around 6,500 years ago. From there, the idea spread north, reaching places like the British Isles, the Netherlands, and southern Scandinavia. Each region then developed its own unique styles and building methods for these monuments.

Archaeologists still debate the exact purpose of long barrows. Some think they were religious sites, perhaps used to honor ancestors or as part of a new religion spreading across the land. Others believe they were more about land and territory, acting as markers to show which areas belonged to different farming communities. People continued to use these long barrows for a long time after they were built. Even during Roman times and the Early Middle Ages, some were reused as burial grounds. For centuries, people interested in history, called antiquarians, and later archaeologists, have studied them. Our knowledge about long barrows comes mostly from these archaeological digs. Some barrows have even been rebuilt and are now popular tourist spots or sacred places for modern religious groups.

Contents

What are Long Barrows?

Long barrows have different names depending on where they are in Western Europe. The word "barrow" itself is an old English word for an earthen mound. In other parts of Britain, they were called "low," "tump," "howe," or "cairn" (especially for stone mounds). Another common term is "dolmen", which is a word from the Breton language meaning "table-stone." This term usually refers to the stone chambers found inside some long barrows.

The historian Ronald Hutton suggested calling these sites "tomb-shrines." This name shows that they were likely used both to bury the dead and for special ceremonies. Some barrows have no burials at all, while others contain the remains of up to fifty people!

Chambered and Earthen Barrows

Early archaeologists used to call these monuments "chambered tombs." Most of the time, builders used local stone if it was available. So, the choice between using wood or stone for a long barrow probably depended on what materials were easiest to find.

The stone chambers inside long barrows come in two main types. Some were dug into the earth, while others were built above ground. Many chambered long barrows had smaller side rooms, sometimes making the inside look like a cross shape. Others were simpler, with just one main chamber.

Some long barrows don't have any chambers inside them. These are often called "unchambered" or "earthen" barrows. They might have been built with timber because stone wasn't available in that area. It's important to remember that even though they look different, both types of long barrows were part of the same ancient tradition.

How They Were Built

Long barrows are usually single mounds of earth, with ditches running along their sides. They are typically between 20 and 70 meters (65 to 230 feet) long. Building a long barrow in the Early Neolithic period would have taken a lot of teamwork and effort. Remember, people didn't have metal tools back then!

The style and materials used often changed from one region to another. For example, in northern and western Britain, long barrows often had stone mounds with chambers. But in southern and eastern Britain, they were usually made of earth. Many barrows were also changed and updated over the years they were used. It can be tricky for archaeologists to figure out exactly when a barrow was first built because of all these changes.

Long barrows share some similarities with other ancient monuments from Neolithic Europe, like bank barrows and cursus monuments. Bank barrows look like long barrows but are much, much longer. Cursus monuments also have parallel ditches but stretch for even greater distances. Studies show that many long barrows were built in wooded areas. In Britain, they were often placed on hillsides, overlooking rivers and valleys. They were also often built near causewayed enclosures, another type of earthen monument.

Where Long Barrows Are Found

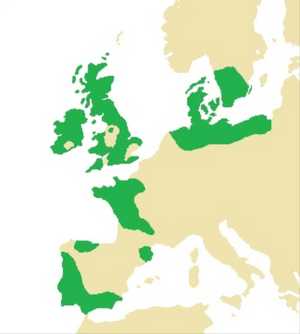

Around 40,000 long barrows from the Early Neolithic period are still known to exist across Europe. You can find them all over Western Europe, from southern Spain up to southern Sweden, and across the British Isles. While they aren't the very first stone structures in the world (that's Göbekli Tepe in Turkey), they are the oldest widespread tradition of using stone in building. Archaeologists describe them as the "oldest built structures in Europe" that are still standing. Even though they are found across a huge area, they have clear regional differences in how they were built.

Archaeological digs show that some of the oldest long barrows were built in Spain, Portugal, and western France around 6,500 years ago. This means the building style likely started in this southern part of Western Europe and then spread north along the Atlantic coast. It reached Britain by about 6,000 years ago, around the same time farming arrived. Later, it spread further north into mainland Europe, reaching places like the Netherlands around 5,500 years ago.

Later in the Neolithic period, people started focusing more on burying individuals, which might suggest that society was becoming more organized with different social levels. One of the last chambered tombs ever built was Bryn Celli Ddu in Wales, long after people stopped building them in most of Europe. This suggests that its builders might have been trying to bring back older traditions.

Archaeologists like David Field and Caroline Malone describe long barrows as some of the most famous and impressive ancient monuments in Britain. They can still make people feel amazed and curious today, even with all our modern buildings.

Different Styles in Different Regions

In southern Spain, Portugal, southwestern France, and Brittany, long barrows usually have large stone chambers.

In Britain, earthen long barrows are more common in the southern and eastern parts of the island. About 300 earthen long barrows are known across eastern Britain, from Scotland down to the south coast. These were likely built between 5,800 and 5,000 years ago.

Another important style in western Britain is the Cotswold-Severn Group. These are usually chambered long barrows and often contain a lot of human bones, sometimes 40 to 50 people in each! Long barrows in the Netherlands and northern Germany also used stone where it was available. In parts of Poland, the barrows are typically made of earth. Further north, in Denmark and southern Sweden, long barrows usually used stone.

What Were They Used For?

The exact purpose and meaning of Early Neolithic long barrows are still a mystery. Archaeologists can only make educated guesses based on what they find. There isn't one single answer that everyone agrees on. One archaeologist, Frances Lynch, suggested that long barrows probably played "broad religious and social roles" for the communities who built them, similar to how churches are used today.

Burial Places

Many long barrows were indeed used as tombs to bury deceased people. That's why archaeologists sometimes call them "houses of the dead." However, interestingly, many long barrows that have been dug up show no signs of human remains. This suggests they were more than just tombs. Archaeologists David Lewis-Williams and David Peace believe they were also "religious and social centers," places where the living visited the dead and kept their connections with ancestors strong.

Sometimes, the bones placed in the chambers were already old when they were put there. In other cases, bones might have been added long after the barrow was built. It's even possible that some bones were removed and replaced during the Early Neolithic period itself. The human remains found in long barrows often included a mix of men, women, and children. The bones of different people were often mixed together. This might have been a way to show that everyone was equal after death, no matter their wealth or status.

Not everyone who died in the Early Neolithic was buried in these long barrows. We don't know how people decided who got buried there and who didn't. It's possible that many people's bodies were left out in the open air. We also don't know where the process of preparing the bones (called excarnation, where flesh is removed) took place before they were put into the chambers. Some human bones have been found in the ditches of other ancient monuments called causewayed enclosures. The holes found in front of many long barrows might have been for platforms where this process happened.

In some chambers, human remains were carefully arranged by bone type or by the age and sex of the person. This suggests a very organized way of dealing with the dead. Rarely, archaeologists find "grave goods" (items buried with the dead) inside long barrows. When they do, these items are usually seen as leftovers from funeral ceremonies or feasts. The types of grave goods found varied by region. For example, in the Cotswold-Severn Group in England, cattle bones were often found in the chambers, treated almost like human remains.

Sometimes, human remains were placed in the chambers over many centuries. For example, at West Kennet Long Barrow in England, bones were placed there over a period of 1,500 years! This shows that some chambered long barrows were used on and off for a very long time. In some cases, certain bones are missing from the collections found in the chambers. This suggests that some bones might have been deliberately taken out of the chambers for use in special ceremonies.

Religious Places

One idea is that long barrows were important places connected to Early Neolithic beliefs about the universe and spirituality. They might have been centers for special ceremonies involving the dead. The presence of human remains suggests that these barrows were used for a type of ancestor veneration, where people honored their ancestors. Archaeologist Caroline Malone suggested that the importance of these barrows shows that ancestors were much more important to Early Neolithic people than to those who lived before them.

Some archaeologists believe that the entrances to the chambers were seen as special places where rituals took place, perhaps even involving fire to transform the dead.

Land Markers

Another idea is that long barrows were closely linked to the new way of life that came with farming. In this view, long barrows acted as markers for land, showing that a particular area was owned and controlled by a certain community. This would have warned off other groups. Malone noted that each "tomb-territory" usually had access to different types of soil and landscapes nearby, suggesting it could support a community. Also, the way chambered long barrows are spread out on some Scottish islands matches modern farm boundaries. This idea also looks at how other cultures around the world have used monuments to mark their land.

This idea became popular in the 1980s and 1990s. However, in the early 2000s, archaeologists started to question it. Evidence showed that much of Early Neolithic Britain was forested, and people were more likely herders (pastoralists) than full-time farmers. This means communities would have moved around more, so they might not have needed to mark their land so clearly. Also, this idea doesn't explain why long barrows are often grouped together in certain areas instead of being spread out evenly.

Later History of Long Barrows

Many chambered long barrows have not survived perfectly. Over thousands of years, they have been damaged or broken apart. Sometimes, most of the chamber has been removed, leaving only the three-stone "dolmen" part.

Roman and Iron Age Use

During the Iron Age and Roman period (about 2,500 to 1,500 years ago), many British long barrows were used again. For example, at Julliberrie's Grave in Kent, people were buried around the barrow during Roman times. At Wayland's Smithy in Oxfordshire, a cemetery was set up around the barrow with at least 46 skeletons. People also often left coins around long barrows in Roman Britain, perhaps as offerings.

Studying Long Barrows

Serious study of chambered long barrows began in the 1500s and 1600s, often when the mounds covering them were removed for farming. By the 1800s, people who studied old things (antiquarians) and archaeologists realized these monuments were a type of tomb. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, archaeologists like V. Gordon Childe thought that these Western European monuments were based on tombs originally built in the eastern Mediterranean, like Egypt or Crete. They believed the idea spread westward as part of a "megalithic religion."

A very important book about long barrows was written by the Welsh archaeologist Glyn Daniel in 1958. In 1950, Daniel noted that about one-tenth of the known chambered long barrows in Britain had been dug up. Sadly, many early excavations didn't properly record or keep any human remains found. From the 1960s onwards, archaeologists started focusing more on studying groups of long barrows in specific regions. They also realized that long barrows were often changed many times over their long period of use.

Until the 1970s, many archaeologists believed that long barrows in Western Europe were copied from models in the Near East. Studying long barrows has sometimes been difficult because other features have been mistaken for them. For example, long barrows have been confused with rabbit warrens or even old rifle butts. Later landscaping projects have also caused confusion. Damage to Neolithic long barrows can also make them look like other types of mounds, like the oval or round barrows that were built later. In areas that were once covered by glaciers, natural piles of rock and dirt have sometimes been mistaken for long barrows.

New technologies have helped a lot. Aerial photography has been great for finding many more barrows that are hard to see from the ground. Geophysical surveys use special equipment to explore sites underground without digging, which is very helpful for places that can't be excavated.

Modern Use

Long barrows like West Kennet Long Barrow in England have become popular tourist attractions. At Wayland's Smithy, visitors have been putting coins into cracks in the stones since at least the 1960s. At the Coldrum Long Barrow, people have tied rags to a tree hanging over the barrow, like a wish tree.

Many modern Pagans see West Kennet Long Barrow as a "temple" and use it for their ceremonies. Some see it as a place connected to ancestors, where they can go for spiritual experiences. Others view it as a symbol of the Great Goddess. The winter solstice (the shortest day of the year) is a very popular time for Pagans to visit.

Amazingly, in 2015, the first new long barrow in thousands of years was built in England, inspired by the ancient ones! This was the Long Barrow at All Cannings in Wiltshire. Soon after, others were built, like Soulton Long Barrow in Shropshire.

Images for kids

-

A well-preserved earthen long barrow on Gussage Down in the Cranborne Chase area of Dorset, England

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |