Athanasius Kircher facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Athanasius Kircher

|

|

|---|---|

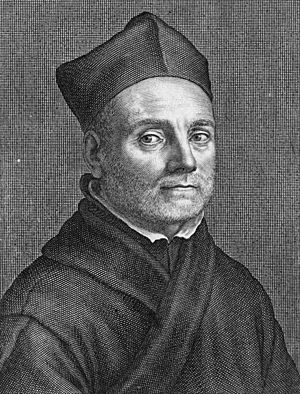

Portrait from Mundus Subterraneus (1664)

|

|

| Born | 2 May 1602 Geisa, Princely Abbey of Fulda

|

| Died | 27 November 1680 (aged 78) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions |

|

Athanasius Kircher (born May 2, 1602 – died November 27, 1680) was a German scholar and a member of the Jesuit order. He was a true polymath, meaning he knew a lot about many different subjects. Kircher wrote about 40 major books, especially on topics like different religions, the study of the Earth (geology), and medicine.

People have compared Kircher to famous thinkers like Leonardo da Vinci because he was interested in so many things. He was even called the "Master of a Hundred Arts." He taught for over 40 years at the Roman College in Rome, where he created a special room filled with amazing objects, like a museum. Today, many scholars are becoming interested in Kircher's work again.

Kircher thought he had figured out the ancient Egyptian writing. However, most of his ideas and translations were later found to be wrong. Still, he correctly saw the connection between ancient Egyptian and the Coptic language. Some people even call him the founder of Egyptology, which is the study of ancient Egypt.

Kircher also loved Sinology, the study of China. He wrote a huge book about China. In it, he mentioned early Christians there and tried to link China to Egypt and Christianity.

In geology, Kircher studied volcanoes and fossils. He was one of the first people to look at tiny living things (microbes) using a microscope. He was ahead of his time when he suggested that the plague was caused by tiny, invisible microorganisms. He also suggested good ways to stop the disease from spreading.

Kircher was very interested in technology and machines. Some inventions linked to him include a magnetic clock and early automatons (self-moving machines). He also helped develop the first megaphone. While he didn't invent the magic lantern, he studied how it worked in his book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae.

Kircher was a scientific superstar in his time. But later, thinkers like René Descartes focused more on pure logic, and Kircher's ideas seemed less important. However, in recent times, people have started to appreciate the beauty and wonder in his work again. One expert called him "a giant among seventeenth-century scholars" and "one of the last thinkers who could rightfully claim all knowledge as his domain."

Life of Athanasius Kircher

Kircher was born on May 2, either in 1601 or 1602. He wasn't even sure of his exact birth year! He was born in Geisa, a town in what is now Germany. From 1614 to 1618, he attended the Jesuit College in Fulda. After that, he joined the Jesuit order.

Kircher was the youngest of nine children. He loved rocks and volcanoes, which led him to study them. He learned Hebrew from a rabbi while also attending school. He studied philosophy and theology in Paderborn. But in 1622, he had to escape to Cologne to avoid soldiers. During his journey, he almost died when he fell through ice while crossing the frozen Rhine river. This was just one of many times his life was in danger.

From 1622 to 1624, Kircher taught in Koblenz. Then he taught mathematics, Hebrew, and Syriac in Heiligenstadt. There, he created a show with fireworks and moving scenery for a visiting leader. This showed his early interest in mechanical devices. In 1628, he became a priest. He then became a professor of ethics and mathematics at the University of Würzburg, where he also taught Hebrew and Syriac. Around this time, he also started to become interested in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

In 1631, while in Würzburg, Kircher supposedly had a vision of bright light and armed men. Soon after, Würzburg was attacked and captured. People thought he had predicted this using astrology, but Kircher said he hadn't. That year, he published his first book, Ars Magnesia, about magnetism. Because of the Thirty Years' War, he had to move to the papal University of Avignon in France.

In 1633, the emperor asked him to come to Vienna to take over from the famous scientist Johannes Kepler. But another scholar, Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc, arranged for Kircher to go to Rome instead to continue his studies. Kircher had already left for Vienna, but his ship was blown off course, and he ended up in Rome anyway!

He stayed in Rome for the rest of his life. From 1634, he taught mathematics, physics, and Oriental languages at the Collegio Romano. Later, he was allowed to focus only on his research. He studied diseases like malaria and the Black Death. He collected many old objects and his own inventions, which he displayed in the Museum Kircherianum.

In 1661, Kircher found the ruins of a church built by Constantine. He raised money to rebuild it as the Santuario della Mentorella. When he died, his heart was buried there.

Kircher's Amazing Books

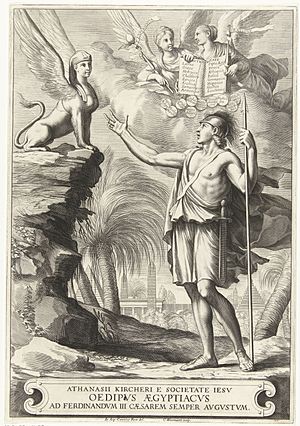

Kircher wrote many big books on a huge range of topics. These included Egyptology (the study of ancient Egypt), geology (the study of Earth), and music theory. He didn't see strict lines between different subjects, which is common today. For example, his book Magnes was about magnetism, but it also talked about other kinds of attraction, like gravity and even love! Perhaps his most famous work today is Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1652–54). This was a massive study of Egyptology and different religions.

His books were written in Latin and were read widely in the 1600s. They helped spread scientific information to many people. Today, Kircher isn't seen as someone who made many completely new discoveries. However, his work helped set the stage for future scientists.

Studying Languages and Cultures

Unlocking Egyptian Hieroglyphs

The last known example of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing is from 394 AD. After that, people forgot how to read them. For a long time, the main idea about hieroglyphs came from a Greek writer named Horapollon. He wrongly thought they were "picture writing" and that each picture had a secret symbolic meaning.

Kircher was the most famous person who tried to "decode" hieroglyphs before modern times. In his book Lingua Aegyptiaca Restituta (1643), Kircher called hieroglyphs a "language hitherto unknown in Europe." He said it had "as many pictures as letters, as many riddles as sounds." While many of his ideas were wrong, some parts of his work were useful to later scholars. Kircher helped start Egyptology as a serious field of study.

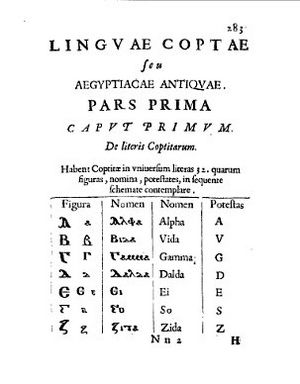

Kircher became interested in Egyptology in 1628. He saw a collection of hieroglyphs in a library and was fascinated. In 1633, he learned Coptic, which is the language of Christians in Egypt. In 1636, he published the first grammar book for Coptic. Kircher believed that Coptic was the last form of ancient Egyptian. Because of this, some people call him the true "founder of Egyptology." His work happened before the Rosetta Stone was discovered, which later helped scholars understand hieroglyphs. He also saw the connection between hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts (another ancient Egyptian writing style).

Between 1650 and 1654, Kircher published four books with his "translations" of hieroglyphs. However, none of them were close to the real meanings. In Oedipus Aegyptiacus, Kircher thought that ancient Egyptian was the language spoken by Adam and Eve. He also believed that hieroglyphs were secret symbols that couldn't be translated by words alone. For example, he translated a simple hieroglyphic text that actually means "Osiris says" into a long, complicated sentence about gods and nature.

Even though his methods were flawed, Kircher's work collected a lot of information. This data was later used by Jean-François Champollion when he successfully decoded the hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone.

Exploring China

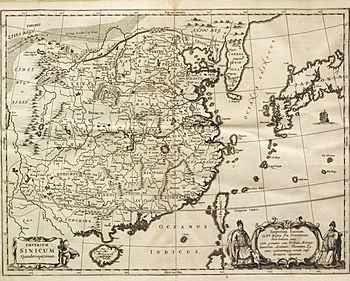

Kircher was interested in China from a young age. In 1629, he even told his boss he wanted to become a missionary there. In 1667, he published a huge book called China Illustrata (China Illustrated). This book was like an encyclopedia, covering many topics. It included accurate maps but also mythical things, like a study of dragons. The book used information from other Jesuits who were working in China.

China Illustrata highlighted Christian parts of Chinese history. It noted the early presence of Nestorian Christians in China. But Kircher also wrongly claimed that the Chinese were descended from Noah's son Ham. He also thought that Confucius was like Moses and that Chinese characters were simplified hieroglyphs.

Studying the Bible

In 1675, Kircher published Arca Noë, which was his research on Noah's Ark from the Bible. He looked at the Ark's size. Based on the number of animal species he knew (not counting insects), he figured there would have been enough space. He also thought about how the Ark journey would work, like feeding the meat-eating animals and the daily schedule for caring for all the animals.

Physical Sciences

Understanding Earth (Geology)

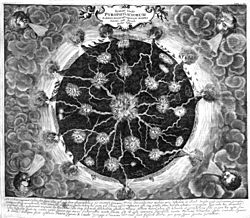

In 1638, Kircher visited southern Italy. He was so curious that he was lowered into the crater of Vesuvius, which was about to erupt, to see inside! He was also interested in the rumbling sounds he heard under the ground near the Strait of Messina. His studies of geology and geography led to his book Mundus Subterraneus (Underground World) in 1664. In this book, he suggested that the tides were caused by water moving in and out of a huge underground ocean.

Kircher was also puzzled by fossils. He understood that fossils were the remains of animals. He thought very large bones might belong to giant humans. He also believed that mountain ranges were like the Earth's bones, exposed by weather.

Mundus Subterraneus also included pages about the legendary island of Atlantis. It had a map with a Latin caption that means "Site of the island of Atlantis, in the sea, from Egyptian sources and Plato's description."

Biology and Life

In his book Arca Noë, Kircher suggested that after the Great Flood, new animal species changed as they moved to different places. For example, he thought a deer might become a reindeer in a colder climate. He also believed that some species were mixes of others, like armadillos being a mix of turtles and porcupines. Some historians see these ideas as early thoughts about evolution.

Medicine and Health

Kircher had very modern ideas about studying diseases. As early as 1646, he used a microscope to look at the blood of people who had the plague. In his book Scrutinium Pestis (1658), he saw "little worms" or "animalcules" in the blood. He correctly concluded that the disease was caused by tiny microorganisms. While he likely saw blood cells, not the actual plague germs, his idea was right! He also suggested hygienic ways to stop the disease from spreading. These included isolating sick people, quarantine (keeping people separate), burning infected clothes, and wearing facemasks to avoid breathing in germs.

Technology and Inventions

In 1646, Kircher published Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae, a book about showing images on a screen. This was similar to the magic lantern, a device that projected pictures. Kircher described how to build a "catastrophic lamp" that used mirrors to project images onto a wall in a dark room. He improved on earlier models and suggested ways people could use his device. He also helped explain that these projected images were natural, not magical.

Before Kircher, such images were sometimes used to make people think they were seeing supernatural things. Kircher made sure to tell people that these images were just natural effects, not magic.

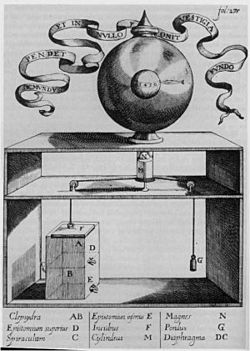

Kircher also built a magnetic clock, which he explained in his book Magnes (1641). This clock had been invented by another Jesuit, but Kircher improved it. The clock used a magnetic sphere that rotated. Kircher showed that the movement could be caused by a water clock inside the device. This helped disprove the idea that the sun's magnetic force caused the sphere to move, which some thought supported the idea that the Earth goes around the sun.

His book Musurgia Universalis (1650) shared Kircher's ideas about music. He believed that the harmony in music reflected the perfect order of the universe. The book included plans for water-powered automatic organs and drawings of musical instruments. One picture even showed the differences between the ears of humans and animals. In Phonurgia Nova (1673), Kircher thought about how to send music to far-off places.

Other machines Kircher designed included an aeolian harp (played by wind) and automatons. One automaton was a statue that could speak and listen using a speaking tube. He even thought about a perpetual motion machine, which would run forever without stopping.

In Phonurgia Nova, Kircher also looked at how sound works. He explored using horns and cones to make sound louder in buildings. He also studied echoes in rooms with different shaped domes. He even looked into how music might help people with tarantism, a condition from southern Italy.

Combinatorics and Puzzles

Kircher also worked on ways to create and count all possible combinations of a group of objects. He based his ideas on earlier work by Ramon Llull. His methods are discussed in his book Ars Magna Sciendi, sive Combinatoria (1669). He even drew what might be the first pictures of certain types of graphs, which are like diagrams used in math. Kircher also used these ideas in his Arca Musarithmica. This was a device that could create millions of church hymns by randomly combining musical phrases!

Kircher's Lasting Impact

His Influence on Scholars

For most of his life, Kircher was a huge scientific star. One historian called him "the first scholar with a global reputation." He was important for two reasons: he did his own experiments, and he also gathered information from over 760 scientists, doctors, and fellow Jesuits all over the world. The Encyclopædia Britannica called him a "one-man intellectual clearing house." His books, filled with his own illustrations, were very popular. He was one of the first scientists who could make a living just by selling his books. However, towards the end of his life, his popularity dropped as new ideas from thinkers like René Descartes became more popular.

His Cultural Legacy

Kircher was mostly forgotten until the late 1900s. Some people think he was rediscovered because his wide-ranging approach is similar to modern ways of thinking.

Since few of Kircher's works have been translated, people today often focus on how beautiful his illustrations are. Many exhibitions have shown the amazing artwork in his books. Famous writer Umberto Eco has written about Kircher in his novels and non-fiction books. In the historical novel Imprimatur (2002), Kircher plays an important role. His ideas about music's healing power help solve a mystery.

The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles has a special room dedicated to Kircher's life. His collection of cultural objects is in the Pigorini National Museum of Prehistory and Ethnography in Rome.

A book by John Glassie, A Man of Misconceptions, shows connections between Kircher and famous people like Gianlorenzo Bernini and Isaac Newton. It also suggests he influenced writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Jules Verne.

Glassie writes that Kircher should be remembered "for his effort to know everything and to share everything he knew." He was a person who asked many questions about the world and made others ask questions too. He was a source of many ideas—some right, some wrong, some strange, but all amazing.

See also

In Spanish: Atanasio Kircher para niños

In Spanish: Atanasio Kircher para niños

- Abacus Harmonicus

- List of Jesuit scientists

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Filippo Bonanni, S.J., pupil of Kircher

- Cat organ, a strange musical instrument idea by Kircher

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |