Magic lantern facts for kids

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name lanterna magica, was an early type of projector that showed pictures. It used paintings, prints, or photographs on clear glass plates, one or more lenses, and a light source. It was mostly created in the 1600s and was very popular for entertainment. Later, in the 1800s, it was also used for teaching. By the late 1800s, smaller toy versions were made for kids. Magic lanterns were widely used from the 1700s until the mid-1900s. Then, a smaller projector that could hold many 35 mm photographic slides, called the slide projector, took its place.

Contents

How Magic Lanterns Work

The Machine Itself

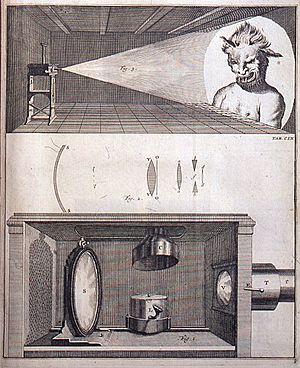

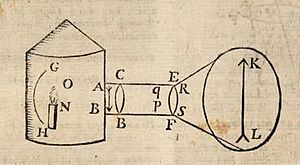

A magic lantern had a curved mirror behind a light source. This mirror helped to send the light through a small, clear glass plate called a "lantern slide," which had the picture on it. The light then went through a lens at the front of the machine. This lens could be adjusted to focus the picture onto a screen, which could just be a white wall. This created a much bigger image of the slide on the screen. Some early lanterns even used three lenses to make the picture clearer.

Later, in the 1800s, lanterns with two lenses, called biunial lanterns, became common. These made it easy to switch between pictures smoothly. Even stronger light sources were added to improve how photographic slides looked.

The Slides

At first, the pictures were painted by hand directly onto glass slides. Some were painted with black paint, but soon clear colors were also used. Sometimes, the paintings were even done on oiled paper. Often, black paint was used as a background to block out extra light, so only the picture would show up without distracting edges. Many handmade slides were covered with a clear coating or another piece of glass to protect the painting. Most early slides were put into wooden frames with a round or square opening for the picture.

After 1820, factories started making printed slides that were colored by hand. These often used a method called decalcomania to transfer the images. Many factory-made slides were produced on long strips of glass with several pictures on them and had paper glued around their edges.

The very first photographic lantern slides were invented in 1848 by brothers Ernst Wilhelm and Frederick Langenheim in Philadelphia. They called them hyalotypes.

Light Sources

When the magic lantern was invented in the 1600s, the only light sources available (besides sunlight) were candles and oil lamps. These were not very bright and made the projected images quite dim. The invention of the Argand lamp in the 1790s helped make the images brighter. Then, in the 1820s, limelight was invented, which made the pictures much, much brighter!

In the 1860s, the very bright electric arc lamp came along, which meant no more burning gases or dangerous chemicals were needed. Eventually, the electric light bulb made lanterns even safer and easier to use, though not as bright as arc lamps.

What Came Before Magic Lanterns

Several types of projection systems existed before the magic lantern. People like Giovanni Fontana, Leonardo Da Vinci, and Cornelis Drebbel had described or drawn image projectors that were similar to the magic lantern.

In the 1600s, people were very interested in how light and lenses worked. The telescope and microscope were invented around this time. These tools were not just for scientists; they were also popular and fun for people who could afford them. The magic lantern became another exciting invention in this field.

Camera Obscura

The magic lantern can be seen as a step forward from the camera obscura. This is a natural event where an image of a scene outside (like a wall) is projected through a small hole onto a surface inside. The image appears upside down and flipped. People knew about this since at least 500 BC and experimented with it in dark rooms around 1000 AD. Using a lens in the hole started around 1550. Portable camera obscura boxes with lenses were developed in the 1600s.

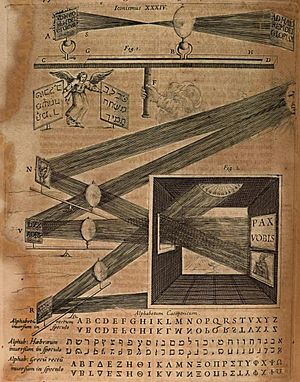

Steganographic Mirror

In 1645, a German scholar named Athanasius Kircher described his "Steganographic Mirror." This was an early projection system that used a lens and pictures painted on a curved mirror to reflect sunlight. It was mostly meant for sending messages over long distances. Kircher hoped someone would find a way to make it better.

Who Invented the Magic Lantern?

Christiaan Huygens

Today, most people agree that the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens was the true inventor of the magic lantern. He knew about Athanasius Kircher's earlier projection ideas. Huygens' father, Constantijn, had even seen a camera obscura from Cornelis Drebbel in 1622 and was very excited about it.

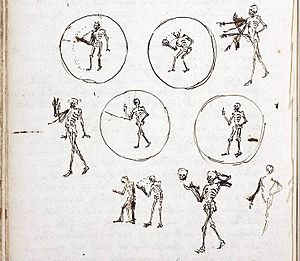

The oldest known paper about the magic lantern is a page where Christiaan Huygens drew ten small sketches of a skeleton taking off its skull. He wrote above them, "for representations by means of convex glasses with the lamp." This page was found with other papers from 1659, so it's believed he made it that year. Huygens later seemed to regret his invention, thinking it was too silly. In a letter in 1662, he called it an old "bagatelle" (a trifle) and worried it would hurt his family's reputation if people found out he invented it. He even asked his brother to break a lantern he had sent to their father, because his father planned to show it to King Louis XIV of France!

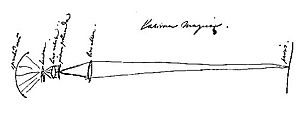

Christiaan first called the magic lantern "la lampe" (the lamp) or "la lanterne" (the lantern). But in his later years, he started using the common term "laterna magica" in his notes. In 1694, he drew how a "laterna magica" worked, showing its two lenses.

Walgensten, the Dane

Thomas Rasmussen Walgensten (around 1627–1681) was a mathematician from Gotland. He studied at the university of Leyden and might have met Christiaan Huygens there. From 1664 to 1670, Walgensten showed the magic lantern in different cities like Paris, Rome, and Copenhagen. Athanasius Kircher wrote in 1671 that Walgensten "sold such lanterns to different Italian princes in such an amount that they now are almost everyday items in Rome." Walgensten is also thought to have created the name "Laterna Magica."

Moving Pictures with Magic Lanterns

The magic lantern was not just a way to show still pictures; it could also project moving images!

Sometimes, movement was suggested by quickly switching between pictures that showed different parts of a motion. But most magic lantern "animations" used two glass slides projected together. One slide had the part of the picture that stayed still, and the other had the part that could be moved by hand or by a simple machine.

Movement in these animated slides was usually limited to two steps of a motion or a slow, continuous movement, like a train moving through a landscape. This made subjects with repeated movements popular, such as windmill sails turning or children on a seesaw. These movements could be repeated over and over at different speeds.

Another common trick was like a camera panning across a scene. A long slide would be slowly pulled through the lantern, often showing a landscape or different parts of a story.

Projected images could also move by moving the magic lantern itself. This became a key trick in phantasmagoria shows in the late 1700s. The lantern would often slide on rails or small wheels, hidden behind the projection screen so the audience couldn't see it.

Different Types of Mechanical Slides

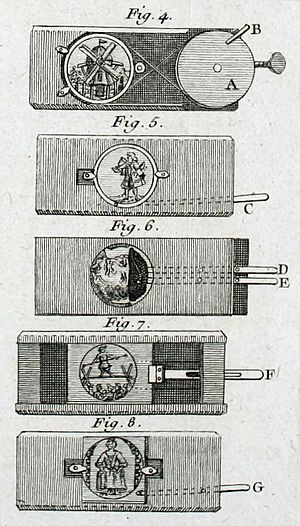

Many different types of machines were used to add movement to the projected image:

- Slipping slides: A movable glass plate with one or more figures was slipped over a stationary one, either by hand or with a small handle. For example, a tightrope walker could slide across a rope. Another common example showed a creature that could move its eyes in all directions. Long glass pieces could show a parade of figures or a train with many cars.

- Slipping slides with masking: Black paint on the moving plate would hide parts of the picture on the stationary glass. This allowed parts of the image, like a person's arm, to disappear and reappear in a new position, making it look like it was moving. This movement was often quick and jerky. Masking was also used to change things, like replacing a person's head with an animal's head.

- Lever slides: A moving part was controlled by a lever. These could show more natural movements and were often used for repeated actions, like a woodcutter raising and lowering his axe, or a girl on a swing.

- Pulley slides: A pulley would spin the moving part, for example, to make the sails on a windmill turn.

- Rack and pinion slides: Turning a handle would rotate or lift the moving part. This could be used for turning windmill sails or making a hot air balloon take off and land. A more complex slide showed planets orbiting the sun.

- Fantoccini slides: These had figures with moving joints, controlled by levers or thin rods. A popular one showed a monkey doing somersaults. These were named after Italian animated puppets.

- A snow effect slide could add falling snow to another slide, especially a winter scene. It used a flexible loop of material with tiny holes that moved in front of one of the lenses.

Mechanical slides could also create cool abstract effects:

- The Chromatrope: This slide made amazing colorful geometric patterns by spinning two painted glass discs in opposite directions.

- The Eidotrope: This used two spinning discs of metal or cardboard with holes in them. It created swirling patterns of bright white dots.

- The Kaleidotrope: This slide had a single metal or cardboard disc with holes, hanging on a spring. When tapped, the disc would vibrate and spin, sending colored dots of light swirling into all sorts of shapes.

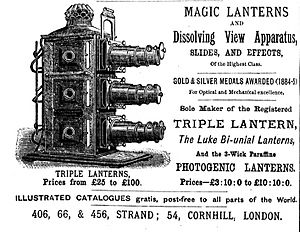

Dissolving Views

A popular magic lantern trick in the 1800s was called a "dissolving view." This was a gradual change from one image to another, much like a "dissolve" in modern movies. For example, a landscape might slowly change from day to night, or from summer to winter. This was done by lining up two matching images and slowly dimming the first image while bringing up the second one.

The idea for this effect is said to have been invented by Paul de Philipsthal around 1803 or 1804. He first thought of using two lanterns to make a ghost appear from a mist. While working on that, he realized he could use the same trick for landscapes.

Another possible inventor was Henry Langdon Childe, who may have worked for De Philipsthal. He is said to have invented dissolving views in 1807 and made them even better by 1818. The term "dissolving views" first appeared on playbills for Childe's shows in London in 1837. He made them very popular at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in the early 1840s.

Later, special biunial lanterns with two projection systems in one machine were made to make dissolving views easier to create. Even triple lanterns were made, allowing for extra effects, like snow falling while a green landscape changed into a snowy winter scene.

Early Movie-like Systems

Some magic lanterns were used to project spinning discs, similar to the phenakistiscope. These had a spinning mechanism and a shutter system.

The Choreutoscope was invented around 1866. It projected six pictures from a long slide and used a hand-cranked machine to move the slide in steps and open/close a shutter at the right time. This mechanism was very important for the development of movie cameras and projectors.

John Arthur Roebuck Rudge built a lantern for William Friese-Greene that could project a sequence of seven photographic slides. These slides showed a man taking off his head with his hands and holding it up! This was probably the very first projection of a trick photography sequence.

Phantasmagoria: Ghost Shows!

Phantasmagoria was a type of horror theater that used one or more magic lanterns to project scary images, especially ghosts. Showmen used tricks like projecting from behind the screen, using mobile projectors, and other effects to make people believe they were seeing real spirits. These shows were very popular in Europe from the late 1700s to well into the 1800s.

It's believed that people used optical devices like curved mirrors and camera obscuras in ancient times to trick audiences into thinking they saw gods or spirits. But it was the magician "physicist" Phylidor who created what was likely the first true phantasmagoria show in Vienna from 1790 to 1792. He probably used mobile magic lanterns with the newly invented Argand lamp. Phylidor claimed his shows revealed how tricksters had fooled their audiences. He later brought his "Phantasmagorie" to Paris in 1792, possibly using the term for the first time.

One of the many showmen inspired by Phylidor was Etienne-Gaspard Robert. He became very famous with his own "Fantasmagorie" show in Paris from 1798 to 1803. He even patented a mobile "Fantascope" lantern in 1798.

Royal Polytechnic Institution Shows

When it opened in 1838, The Royal Polytechnic Institution in London became a very popular place for many kinds of magic lantern shows. In its main theater, which had 500 seats, lantern operators used a set of six large lanterns on tracks to project detailed images from extra-large slides onto a huge screen. The magic lantern was used to help explain lectures, add to concerts, and be part of plays and other theater shows. Popular magic lantern presentations included Henry Langon Childe's dissolving views, his chromatrope, phantasmagoria, and mechanical slides.

Utushi-e: Japanese Magic Lanterns

Utushi-e is a type of magic lantern show that became popular in Japan in the 1800s. The Dutch probably brought the magic lantern to Japan before the 1760s. A new style for these shows was started by Kameya Toraku I, who first performed in 1803. It's possible that the phantasmagoria shows popular in the West inspired the Japanese use of rear projection, moving images, and ghost stories. Japanese showmen created lightweight wooden projectors that could be held by hand. This allowed several performers to move projections of different colorful figures around the screen at the same time. Western mechanical slide techniques were combined with traditional Japanese skills, especially from Karakuri puppets, to make the figures move even more and create special effects.

Magic Lanterns Today

Some fans believe that the bright colors in old lantern slides are still better than what modern projectors can do. Magic lanterns and their slides are still popular with collectors and can be found in many museums. However, out of the original lanterns from the first 150 years after their invention, only 28 are known to still exist (as of 2009).

Museums usually prefer not to use their old slides for projections because they are fragile. Instead, they often show videos of the slides.

A research project called A Million Pictures worked from 2015 to 2018 to help preserve the huge number of lantern slides in libraries and museums across Europe.

Real public magic lantern shows are quite rare today. Some performers claim they are the only ones of their kind in their part of the world. These include Pierre Albanese and glass harmonica player Thomas Bloch in Europe, and The American Magic-Lantern Theater. The Magic Lantern Society keeps a list of active lantern performers, with more than 20 in the U.K. and about eight in other parts of the world.

A Dutch theater group called Lichtbende creates modern magical light shows and workshops using magic lanterns.

Images for kids

-

An illustration of a lantern slide showing Bacchus from a 1677 book

See also

In Spanish: Linterna mágica para niños

In Spanish: Linterna mágica para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |