William Friese-Greene facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Friese-Greene

|

|

|---|---|

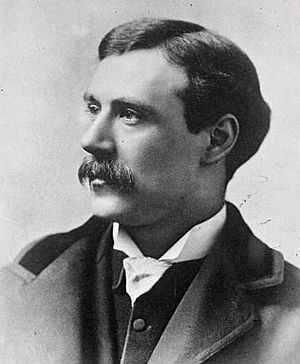

Friese-Greene circa 1890

|

|

| Born | 7 September 1855 Bristol, England

|

| Died | 5 May 1921 (aged 65) London, England

|

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Inventor, photographer |

| Known for | Motion pictures, printing, photography |

| Spouse(s) | Victoria Mariana Helena Friese, Edith Harrison |

| Children | 7 |

William Friese-Greene (born William Edward Green, 7 September 1855 – 5 May 1921) was an English inventor and photographer. He is known as a pioneer in making motion pictures. He created several cameras between 1888 and 1891. He used them to film moving pictures in London. Later, in 1905, he patented an early way to film in two colours. He also invented things for printing, like a way to print without ink. He owned many photography studios. Even though he earned a lot of money from his inventions, he spent it all on new ideas. He went bankrupt three times and died without much money.

Contents

Early Life of a Pioneer

William Edward Green was born on September 7, 1855, in Bristol, England. He went to school at Queen Elizabeth's Hospital. In 1871, he started training with a photographer named Marcus Guttenberg. He later went to court to end his training early.

On March 24, 1874, he married Helena Friese from Switzerland. In a very unusual step for that time, he added her maiden name, Friese, to his own last name. This is how he became Friese-Greene. In 1876, he opened his own photography studio in Bath. By 1881, he had more studios in Bath, Bristol, and Plymouth.

How He Invented Movies

Playing with Light and Pictures

In Bath, Friese-Greene met John Arthur Roebuck Rudge. Rudge made scientific tools and used magic lanterns for fun shows. A magic lantern was a bit like an early projector. Rudge built a machine called the Biophantic Lantern. It could show seven photos quickly one after another. This made the pictures look like they were moving. One famous show made it look like Rudge took off his own head!

Friese-Greene was very interested in this machine. He worked with Rudge on many devices in the 1880s. Friese-Greene moved to London in 1885. He realized that heavy glass plates were not good for filming real life. So, he started trying out new paper film rolls. He made them clear with castor oil. After that, he began using celluloid, which was a much better material for movie cameras.

Creating Early Movie Cameras

In 1888, Friese-Greene built some kind of moving picture camera. We don't know exactly what it looked like. On June 21, 1889, he received a patent for a movie camera. He worked with an engineer named Mortimer Evans on this. This camera could supposedly take up to ten pictures every second. It used both paper and celluloid film.

A newspaper called Photographic News wrote about his camera in February 1890. In March, Friese-Greene sent details about it to Thomas Edison. Edison's team was also working on a movie system. This report was even printed in Scientific American magazine. In 1890, Friese-Greene worked on a camera that could take 3D moving pictures. While the 3D part worked, there are no records of these films being shown to the public.

Friese-Greene kept working on movie cameras until 1891. Many people saw his projected images in private. However, he never managed to show his moving pictures successfully to a large public audience. His experiments with movies cost him a lot of money. In 1891, he went bankrupt. To pay his debts, he sold the rights to his 1889 camera patent for £500. The patent was never renewed, so it expired.

Experiments with Colour Film

Later, Friese-Greene focused on adding colour to movies. From 1904, he lived in Brighton, where many people were experimenting with colour photography and film. He worked with William Norman Lascelles Davidson. In 1905, they patented a two-colour movie system using special lenses called prisms. They showed this system to the public in 1906. Friese-Greene also held screenings at his photography studio.

He also tried another system. It made black-and-white film look like it had true colour. He filmed each picture frame through different coloured filters. Then, each frame was coloured red or green (and sometimes blue). When these films were shown, they looked like they had colour. But if things moved too fast, you could see red and green lines around them. A more famous system called Kinemacolor had similar issues.

In 1911, a man named Charles Urban sued a company called 'Biocolour'. This company had bought rights to Friese-Greene's 1905 patent. Urban claimed Biocolour's process copied his Kinemacolor patent. However, Friese-Greene had patented and shown his work before Urban's partner, George Albert Smith. Urban won the first case, but a racing driver named Selwyn Edge helped fund an appeal. The higher court said Kinemacolor couldn't do everything it claimed. Urban took the case all the way to the House of Lords, but he lost again in 1915. This decision didn't help anyone. Urban lost control over his own system, and it became useless. For Friese-Greene, the start of World War I and his own money problems meant he couldn't do more with colour film for a while.

His son, Claude Friese-Greene, continued to work on the colour system. After his father died, Claude called it "The Friese-Greene Natural Colour Process." He used it to film a documentary series called "The Open Road." These films show a rare look at Britain in the 1920s in colour. The BBC later featured them in a series called The Lost World of Friese-Greene.

His Final Moments

On May 5, 1921, William Friese-Greene went to a meeting in London. He was not very well-known at this time. The meeting was about problems in the British film industry. Lord Beaverbrook was leading the meeting. Friese-Greene felt upset by the arguments. He stood up to speak. The chairman asked him to come to the stage so everyone could hear him better. He asked both sides to work together. Soon after he sat down, he collapsed. People tried to help him, but he died almost at once from heart failure.

He died without much money. He only had one shilling and ten pence in his pockets. The people from the film industry, who had mostly forgotten him, felt a sudden shock and sadness. A very big funeral was held for him. Many people lined the streets of London to see it. Some cinemas even had a two-minute silence. Money was raised to build a memorial for his grave. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London. His memorial calls him "The Inventor of Kinematography." However, Friese-Greene never used that term himself. He often spoke kindly about other people who worked on moving pictures.

His second wife, Edith Jane, died a few months later from cancer. She is buried with him, along with some of their children.

His Family

After his first wife died, Friese-Greene married Edith Jane Harrison (1875–1921). They had six sons, but one died as a baby. The oldest son, Claude (1898–1943), and the youngest, Vincent (1910–1943), are buried with their parents. Vincent was killed during the Second World War.

His great-grandson is Tim Friese-Greene.

His Lasting Impact

In 1951, a movie about Friese-Greene was made called The Magic Box. It starred Robert Donat. The film was part of the Festival of Britain. Even though it had many famous actors and Robert Donat's acting was praised, it did not do well at the box office. Some writers said the film was not very accurate. However, director Martin Scorsese has said it is one of his favourite films and inspired him.

A photographer from Bristol, Reece Winstone, tried to save Friese-Greene's birthplace. He wanted it to be a museum about movies. But in 1958, the city of Bristol tore it down to make space for six cars to park.

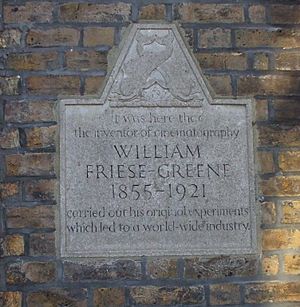

There is a building in Brighton where Friese-Greene had a workshop. Many people wrongly say it was his home. It has a plaque designed in 1924 by Eric Gill. The plaque celebrates Friese-Greene's work. It wrongly says he invented cinematography there. The actor Michael Redgrave, who was in The Magic Box, unveiled the plaque in 1951. A modern office building nearby is named Friese-Greene House. Other tributes include a large sculpted head of "William Friese-Greene" on the outside of the Odeon Cinema in Chelsea. There are also statues of him at Pinewood Studios and Shepperton Studios.

In 2006, the BBC showed a series called The Lost World of Friese-Greene. It was about Claude Friese-Greene's road trip across Britain from 1924 to 1926. He filmed it using his father's colour process. Modern TV technology helped remove the flickering and colour lines that were problems in the original films. This created a special look at Britain in the mid-1920s in colour.

For a long time, film historians did not give William Friese-Greene much attention. But new research is helping people understand his achievements better. It shows how much he influenced the technical development of cinema.

See also

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |