History of film technology facts for kids

The history of film technology is all about how we learned to record, create, and show moving pictures. Long before movies, people enjoyed showing moving images with things like shadow play and the magic lantern. These old ways of showing pictures greatly influenced how film projectors and movie theaters came to be.

Between 1825 and 1840, important new ideas appeared. These included animation (making pictures seem to move), photography (capturing still images), and stereoscopy (making pictures look 3D). For many years, inventors tried to combine these new technologies with older projection methods. Their goal was to create a perfect illusion of reality, or to record real life exactly as it happened. They even hoped to add color and, after the phonograph was invented in 1877, synchronized sound.

From 1887 to 1894, the first successful short moving picture shows were created. The biggest breakthrough came in 1895 when the first movies longer than 10 seconds were projected for audiences. In the beginning, most motion pictures were about 50 seconds long. They didn't have synchronized sound or natural color. They were mostly shown as exciting new attractions.

In the early 1900s, movies became much longer. Film quickly grew into a major way to share messages and provide entertainment. Synchronized sound arrived in the late 1920s, and full color motion picture film in the 1930s. Even then, black and white films were still very common for many years. By the early 2000s, physical film stock started to be replaced by digital film cameras and projectors.

3D film technology has been around since the start of movies. However, it only became a common option in most movie theatres in the early 2000s.

Other technologies like Television, video, and video games are related to film. But they are usually seen as different types of media. Historically, these new technologies often made the movie industry create new things, like color, wide screens, and 3D, to keep people coming to theaters.

Today, with digitization, many parts of different media overlap with film. This changes how we define "film." For example, a film is usually not shown live, and it's often a single release. Unlike computer games, a film is rarely interactive. The difference between "video" and "film" used to be about how they were recorded. Now, both use digital methods, so there are few technical differences. Generally, "film" means longer, bigger productions best enjoyed by large audiences on a big screen, often telling an emotional story. "Video" usually means shorter, smaller productions meant for home viewing or teaching.

Contents

- Early Moving Pictures: Before Modern Film (Up to 1894)

- Making Pictures Move: Early Animation (1831–1848)

- Adding Photos to Motion: Early Experiments (1849–1870)

- Janssen's Photographic Revolver (1874)

- Donisthorpe's Early Film Ideas (1876–1878)

- Muybridge and the Horse in Motion (1878–1881)

- Marey and Chronophotography (1882–1890s)

- Anschütz's Electrotachyscope (1886–1895)

- Early Film on Paper and Gelatin (1884-1900)

- Early Celluloid Films (1889–1896)

- The Early Movie Industry (1896-1910s)

- Solving the Flicker Problem

- Color Films

- Synchronized Sound

- 3D Movies

- 4D Experiences

- Interactive Film and Virtual Reality

- Widescreen and 360° Film

- Digital Film

- See also

Early Moving Pictures: Before Modern Film (Up to 1894)

The technology for film grew from improvements in projection, lenses, photography, and optics.

Some early ways to show moving pictures or projections include:

- Shadowgraphy: This art of making shadows with your hands has probably existed since ancient times.

- Camera obscura: This natural effect, like a pinhole camera, might have been used by artists for a very long time.

- Shadow puppetry: This art form, using puppets to create shadows, may have started around 200 BCE in Asia.

- Magic lantern: Invented in the 1650s, this device projected painted glass slides.

- Stroboscopic animation devices: These toys made pictures seem to move. Examples include the phenakistiscope (since 1833), zoetrope (since 1866), and flip book (since 1868).

The camera obscura is a natural event where light passes through a small hole into a dark room, projecting an upside-down image on a surface. It was sometimes used to entertain small groups. People also believed it was used by magicians or priests to make spirits or gods appear. Lenses were added to camera obscuras around 1550. By the 17th century, they became popular drawing aids, first as tents, then as portable wooden boxes. Around 1790, these box cameras were adapted to become photographic cameras by capturing images on light-sensitive paper or plates.

Around 1659, Christiaan Huygens developed the magic lantern. It projected colorful images painted on glass slides. Early magic lantern shows might have even included moving images using special mechanical slides. Around 1790, the magic lantern became key to "phantasmagoria" shows. These shows used rear projection, moving slides, multiple projectors, and even sounds and smells to create scary ghost experiences for audiences. In the 1800s, new magic lantern techniques like "dissolving views" (one image fading into another) and mechanical slides that showed things like falling snow or revolving planets became popular.

Movies are very similar to theater. The old term "photoplay" for movies shows that people thought of them as filmed plays. Things used in theater, like stage lighting and special effects, were quickly used for filming.

Making Pictures Move: Early Animation (1831–1848)

On January 21, 1831, Michael Faraday showed an experiment with a spinning cardboard disc. It had holes that looked like gears. When you looked in a mirror through the holes, some "gears" seemed to stand still while others moved.

In January 1833, Joseph Plateau, who had been doing similar experiments, wrote about his new slotted disc. He showed that if you drew pictures of a moving object in different stages on the disc, they would look like smooth motion when seen in a mirror through the slots. Plateau's Fantascope, later known as the Phénakisticope, became the basis for many future motion picture technologies.

In May 1833, Simon Stampfer published his Stroboscopische Scheiben, which were very similar to Plateau's discs. He also suggested other ideas, like a cylinder (like the later zoetrope) or a long strip of paper looped around rollers for longer scenes, similar to film.

The first public showing of projected animation was by magician Ludwig Döbler on January 15, 1847, in Vienna. He used his patented Phantaskop. People liked the show, even though some complained about the flickering images.

Adding Photos to Motion: Early Experiments (1849–1870)

When photography was invented in 1839, it took a long time to expose a picture. This made it hard to combine with animation. In 1849, Joseph Plateau suggested using a stop motion technique. This would involve taking stereoscopic (3D) photos of plaster models in different positions. He never did it because he became blind. Stereoscopic photography became very popular in the early 1850s.

People hoped photography could also get color and motion to create a more complete illusion of reality. Many inventors started working on these goals.

Antoine Claudet claimed in 1851 to have shown a self-portrait with 12 sides of his face. He later worked on animating stereoscopic photos and created a viewer that showed people moving in two phases.

On November 12, 1852, Jules Duboscq (who made Plateau's Fantascope) added a "Stéréoscope-fantascope, ou Bïoscope" to his patent. It combined Plateau's Fantascope with the stereoscope. It used two small mirrors to reflect stereoscopic image pairs. Only one version was made, but it wasn't a commercial success.

Other ideas for stereoscopic viewers included a double-phenakistiscope and a proto-zoetrope by Johann Nepomuk Czermak in 1855. Coleman Sellers II patented his kinematoscope in 1861.

In 1860, Peter Hubert Desvignes patented many types of cylindrical stroboscopic devices. One version used an endless band of pictures lit by an electric spark. His Mimoscope could show drawings, models, or photos to animate movements.

By the 1850s, the first "instantaneous photography" appeared, making motion photography seem more possible. In 1860, John Herschel thought it would soon be possible to take ten stereoscopic photos per second and combine them with the phenakisticope.

On February 5, 1870, Henry Renno Heyl projected three moving picture scenes with his Phasmatrope to 1500 people in Philadelphia. Each scene was projected from a spinning disk with 16 photos. One disk showed a couple waltzing, repeated four times, with music.

Janssen's Photographic Revolver (1874)

Jules Janssen created a large photographic revolver to record the different stages of the transit of Venus in 1874. This was an early form of time-lapse photography. Some discs with images still exist, but they are test recordings of a model. These photos were likely not meant to be shown as moving pictures. However, much later, images from one disc were turned into a very short stop motion film. Janssen also suggested using the revolver to photograph animals, especially birds.

Donisthorpe's Early Film Ideas (1876–1878)

On November 9, 1876, Wordsworth Donisthorpe applied for a patent for a device to take and show photographs. It would take many pictures at equal times to record changes or movements. The camera would move photographic plates past a lens and shutter. The pictures would then be printed on a paper strip, wound between cylinders, and viewed with a stroboscopic device. However, photographic strips like this weren't available commercially for several years, so Donisthorpe couldn't make motion pictures at this time.

Thomas Edison showed his phonograph on November 29, 1877. An article in Scientific American suggested combining projected photos with the talking phonograph to create a strong illusion of reality. Donisthorpe announced in 1878 that he would combine the phonograph with his "Kinesigraph." He claimed he could make a talking picture of Mr. Gladstone that would move and speak in his own voice.

Muybridge and the Horse in Motion (1878–1881)

In June 1878, Eadweard Muybridge took many sequential photos of Leland Stanford's horses running. He used a line of cameras along the racetrack. The results were published as The Horse in Motion and were praised worldwide. People were surprised by the horses' leg positions. By January 1879, people were putting Muybridge's pictures into zoetropes to watch them move. These were likely the first viewings of photographic motion pictures recorded in real-time.

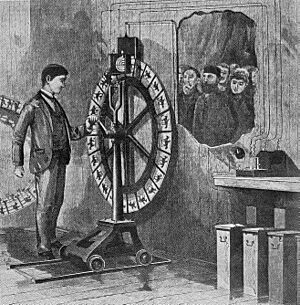

From 1879 to 1893, Muybridge gave lectures where he projected silhouettes of his pictures using a device he called the Zoopraxiscope. He traced slightly distorted pictures from his photographs onto glass discs. One disc showed the skeleton of a horse moving. Muybridge continued studying the movement of animals and people until 1886.

Marey and Chronophotography (1882–1890s)

Many others followed Muybridge's lead and started making sequential photograph series. French scientist Étienne-Jules Marey called this method "Chronophotographie."

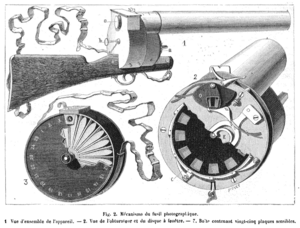

Étienne-Jules Marey had already been studying and recording animal movement for years. His book The Animal Machine (1873) inspired Leland Stanford to find a way to visualize horses' strides. In 1882, Marey began using his chronophotographic gun to study animal movement. It could take 12 pictures per second through a single lens.

Marey was more interested in studying still images than moving ones. Many of his later studies recorded sequential images on a single plate using a new camera system.

Because of Muybridge's success and other chronophotographic achievements, inventors in the late 1800s realized that making and showing photographic "moving pictures" of longer lengths was possible. Many people in this field followed international developments closely through magazines, patents, and talking with other inventors.

Anschütz's Electrotachyscope (1886–1895)

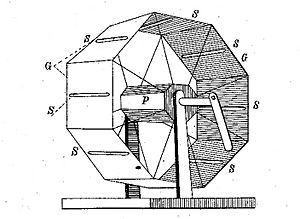

Between 1886 and 1894, Ottomar Anschütz developed several versions of his "elektrische Schnellseher," or Electrotachyscope. His first machine had 24 photos on glass plates on a spinning disk. These were lit from behind by flashing lights. From 1887 to 1890, four to seven people at a time could watch the images on a small screen in a dark room.

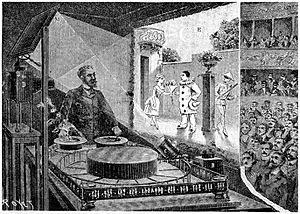

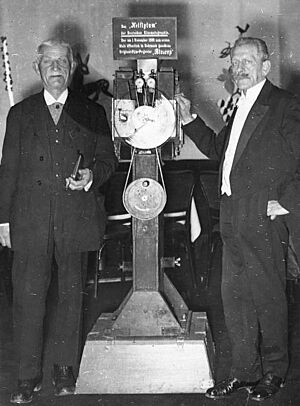

In 1890, Anschütz made a longer, cylindrical version with six small screens. In 1891, Siemens & Halske started making about 152 coin-operated peep-box Electrotachyscope-automats, which were sold worldwide. On November 25, 1894, Anschütz introduced his projector. It used two large spinning disks and continuous light to project images onto a 6 by 8-meter screen for 300 people.

Early Film on Paper and Gelatin (1884-1900)

Anschütz's successful shows used spinning discs or drums, and the repeating loops never had more than 24 images.

In 1884, George Eastman patented his ideas for photographic film. His first film rolls used gelatin with a paper backing as a flexible support for light-sensitive chemicals.

Several film pioneers discovered they could record and show their photos on film rolls. Émile Reynaud seems to have been the first to project moving pictures from long strips of transparent images.

Le Prince's "Animated Pictures" (1886–1889)

The oldest known working motion picture cameras were made by Louis Le Prince in the 1880s. On November 2, 1886, he applied for a US patent for a "Method of and apparatus for producing animated pictures of natural scenery and life." It was granted on January 10, 1888. The patent described a camera with many lenses and some information about a projector. The camera could have three, four, eight, nine, sixteen, or more lenses. It was shown with sixteen lenses in the patent. The images were to be recorded on sensitive films, which could be "an endless sheet of insoluble gelatine coated with bromide emulsion or any convenient ready-made quick-acting paper, such as Eastman's paper film." With sixteen lenses, the camera could record 960 images per minute (16 per second). Le Prince planned for artists to color the pictures.

A sequence of 16 frames of a man walking around a corner has been saved. It seems to have been shot on one glass plate with Le Prince's 16-lens camera in Paris around August 1887. Only 12 frames are complete and clear.

In May 1887, Le Prince developed and patented his first single-lens motion picture camera. He later used it to film Roundhay Garden Scene, a short test shot on October 14, 1888, in Roundhay, Leeds. Le Prince also filmed trams and traffic on Leeds Bridge, plus a few other short films.

Le Prince used paper-backed gelatin films for the negatives. He also looked into using celluloid film and got long rolls from the Lumiere factory.

In 1889, Le Prince developed a single-lens projector with an arc lamp to show his films on a white screen.

Le Prince didn't publish his inventions. His wife planned a demonstration in Manhattan in 1890, but Le Prince disappeared after getting on a train on September 16, 1890.

Reynaud's Théâtre Optique (1888–1900)

Émile Reynaud first mentioned projecting moving images in his 1877 patent for the Praxinoscope. He showed a praxinoscope projection device in 1880 but didn't sell his Praxinoscope à projection until 1882. He then improved it into the Théâtre Optique, which could project longer sequences with separate backgrounds. He patented it in 1888.

He created several Pantomimes Illumineuses for this theater. He painted colorful images on hundreds of gelatin plates, put them in cardboard frames, and attached them to a cloth band. This perforated strip of images could be moved by hand past a lens and mirror system. Simple actions, like one figure hitting another, were repeated by rewinding and forwarding parts of the strip. Some sound effects were synchronized using magnets, and music was played live. From October 28, 1892, to March 1900, Reynaud gave over 12,800 shows to more than 500,000 visitors at the Musée Grévin in Paris.

Early Celluloid Films (1889–1896)

Celluloid photographic film became available for sale in 1889.

William Friese-Greene reportedly used oiled paper for motion pictures in 1885. By 1887, he started working with celluloid. In 1889, Friese-Greene patented a camera that could take up to ten photos per second using perforated celluloid film. He showed his film strips and a projector in June 1890, but couldn't demonstrate the projector.

Le Prince explored using celluloid film and got long lengths from the Lumière factory.

Donisthorpe's interest in moving pictures returned when he heard about Louis Le Prince's work in Leeds. In 1889, Donisthorpe and William Carr Crofts patented a camera using celluloid roll film and a projector. They made a short film of traffic in London's Trafalgar Square.

The Pleograph, invented by Kazimierz Prószyński in 1894, was another early camera that also worked as a projector. It used a rectangle of celluloid with holes between rows of images. Prószyński used an improved Pleograph to film short scenes of life in Warsaw, like people skating.

The Kinetoscope (1891–1896)

Soon after introducing his phonograph in 1877, Thomas Edison heard ideas about combining it with moving images. He wasn't very interested at first. But in October 1888, he registered a patent for "an instrument which does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear." A meeting with Muybridge in February 1888 seems to have prompted this. Edison's employee, W. K. L. Dickson, was put in charge of developing the technology.

Early experiments focused on a device with 42,000 tiny pinhole photographs on a celluloid sheet wrapped around a cylinder, like phonograph cylinders. You would view them through a magnifying lens. This idea was dropped by late 1889. After Edison visited Étienne-Jules Marey, experiments focused on 3/4 inch strips, similar to what Marey used. The Edison company added sprocket holes, possibly inspired by Reynaud's Théâtre Optique.

A prototype of the Kinetoscope was shown to the National Federation of Women's Clubs on May 20, 1891, with the short film Dickson Greeting. This led to a lot of press coverage. Later machines used 35mm films in a coin-operated peep-box. The device was first publicly shown on May 9, 1893, in Brooklyn.

Commercial use began with the first Kinetoscope parlor opening on April 14, 1894. Many more followed in the US and Europe. Edison never tried to patent these outside the US because they relied on technologies already known and patented in other countries.

First Film Screenings (1894-1896)

After Anschütz's Electrotachyscopes and Edison's Kinetoscopes were shown publicly, and their technology described in magazines, many engineers tried to project moving photographs onto a large screen. Döbler, Muybridge, and Reynaud had already successfully projected animated pictures. However, it took a while before anyone managed to publicly show live-action recordings on a large screen.

Newspapers often reported on these developments, but few understood the technology well. Many "inventors" claimed their results were groundbreaking, even if they had copied existing technology or claimed inventions before they were fully ready.

The Eidoloscope, created by Eugene Augustin Lauste for the Latham family, was shown to the press on April 21, 1895. It opened to the public on May 20, showing films of a boxing match. The special Latham loop allowed longer recording and showing of moving images. The boxing films lasted 12 minutes, and the machine could reportedly work for hours.

Max and Emil Skladanowsky showed short movies with their "Bioscop" (a flicker-free projector) from November 1 to 31, 1895, in Berlin. On December 21, their movies were shown as a single event in Hamburg. When they arrived in Paris, they saw the second showing of the Lumière Cinématographe on December 29, 1895. As a result, their planned Bioskop shows in Paris for January 1896 were canceled. The brothers toured with their Bioscop but struggled financially and stopped screenings in 1897.

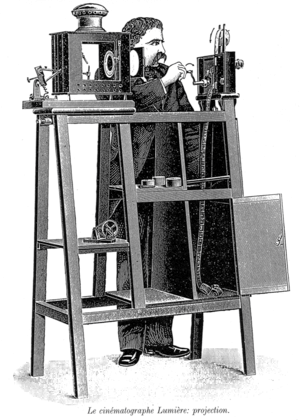

In Lyon, Louis and Auguste Lumière developed the Cinématographe. This machine could take, print, and project film. On December 27, 1895, in Paris, their father Antoine Lumière began showing projected films to paying audiences. The Lumière company quickly became Europe's main producers with their "actualités" (like newsreels) such as Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory and short comedies like The Sprinkler Sprinkled (both 1895).

In Britain, Robert W. Paul and Birt Acres both independently developed their own systems for projecting moving images. Acres showed his in January 1896. Paul unveiled his more important Theatrograph shortly after, on February 20, the same day the Lumières' films were first shown in London. The Theatrograph used a "Maltese cross" system for intermittent film motion. Paul's device was the prototype for the modern film projector and was sold across Europe.

By 1896, the Edison company realized they could make more money by showing movies with a projector to large audiences than with peep-show machines. The Edison company used a projector developed by Armat and Jenkins, called the "Phantoscope," which they renamed the Vitascope. They used it to show films made by Edison and others in France and the UK.

The Early Movie Industry (1896-1910s)

At first, there were no standard rules for film. Producers used different film widths and projection speeds. But after a few years, the 35mm wide Edison film and the 16-frames-per-second projection speed of the Lumière Cinématographe became the standard.

By 1898, Georges Méliès was the biggest maker of fiction films in France. From then on, his films almost always featured special trick effects, which were very popular. His longer films, which were several minutes long from 1899 onwards (while most others were still only a minute long), encouraged other filmmakers to make longer movies too.

Solving the Flicker Problem

Early films often had a noticeable flicker in the projected image. Many systems moved the film strip in stops and starts to avoid blurry motion. A shutter would block the light each time the film moved to the next frame. This flickering was also needed for the "stroboscopic effect" known from earlier animation toys. The constant stopping and starting often damaged the film and could cause the system to jam. If it jammed, the film could burn because it was exposed to the lamp's heat for too long.

Eventually, the solution was a three-bladed shutter. This shutter not only blocked the light during film movement but also more often during projection. The first three-bladed shutter was developed by Theodor Pätzold and was produced by Messter in 1902.

Other systems used a continuous film feed and projected images intermittently using reflections from a spinning mirror carousel, similar to Reynaud's Praxinoscope.

Color Films

Adding Color with Filters (Additive Process)

The first person to show a natural-color motion picture system was British inventor Edward Raymond Turner. He applied for his patent in 1899 and received it in 1900. He showed promising, but mechanically flawed, results in 1902.

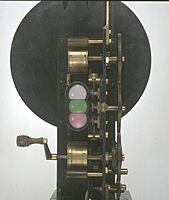

Turner's camera used a spinning disk with three color filters to photograph color separations on one roll of black-and-white film. A red, green, or blue-filtered image was recorded on each successive frame. The finished film was projected, three frames at a time, through the matching color filters.

When Turner died in 1903, his backer, film producer Charles Urban, gave the project to George Albert Smith. By 1906, Smith developed a simpler version he called Kinemacolor. The Kinemacolor camera had red and green filters in its spinning shutter. This meant alternating red-filtered and green-filtered views were recorded on consecutive frames of the black-and-white film. The Kinemacolor projector did the opposite, projecting the frames alternately through red and green filters.

Both devices ran at twice the usual speed to reduce color flicker. Some viewers barely noticed the flicker, but others found it annoying or headache-inducing. A bigger problem was that the two colors weren't photographed at the exact same time. So, fast-moving objects didn't line up perfectly when projected, causing color "fringes" or "ghosts." For example, a white dog wagging its tail might appear to have several tails, colored red, green, and white.

Kinemacolor movies were first shown in 1908. The public first saw Kinemacolor on February 26, 1909, at the Palace Theatre in London. On July 6, 1909, George Albert Smith showed 11 Kinemacolor films to King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra. The King liked the films.

The process first came to the US on December 11, 1909. The Natural Color Kinematograph Company, founded by Urban in 1909, released the first drama filmed in Kinemacolor, By The Order of Napoleon, and the first color newsreel, The Funeral of King Edward VII, both in 1910. They also made the first feature-length documentary, With Our King and Queen Through India, in 1912.

Kinemacolor projectors were installed in about 300 cinemas in Britain, and 54 drama films were made. Four short dramas were made in Kinemacolor in the US (1912–1913) and one in Japan (1914). Kinemacolor was popular with the British royal family. However, the company wasn't a financial success, partly because installing the special projectors was expensive.

A similar method was promoted by William Friese-Greene. He called his system "Biocolour." It was like Kinemacolor, but instead of needing a special projector, alternate frames of the film itself were stained with red and green dyes. This meant an ordinary projector could be used if it could run fast enough. Like Kinemacolor, Biocolour had noticeable color flicker and red and green fringes around moving objects.

In 1912, French film inventor Léon Gaumont introduced Chronochrome, a full-color system. The camera used three lenses with color filters to photograph red, green, and blue color parts at the same time on consecutive frames of one 35mm black-and-white film strip. The projector had three matching lenses. To reduce strain on the film, the frame height was made smaller, creating a widescreen image similar to today's 16:9 aspect ratio.

Chronochrome's color quality was impressive. Because the three frames were exposed and projected at the same time, it avoided Kinemacolor's flicker and color fringes. However, the camera's three lenses couldn't photograph the scene from the exact same viewpoint. So, objects too close to the camera would show color fringes if the projection was optimized for the background, and vice versa. The films were rarely shown outside Gaumont's own cinemas, and the system soon stopped being used.

Technicolor

After trying additive color systems from 1915 to 1921, the Technicolor Motion Picture Corporation developed a new process called subtractive color printing. In their last additive system, the camera had only one lens but used a beam splitter. This allowed red and green-filtered images to be photographed at the same time on nearby frames of a single 35mm black-and-white film strip, which ran through the camera at twice the normal speed.

Two prints were made from the negative on thinner film. They were chemically colored to colors roughly complementary to the filter colors (red for green-filtered images and vice versa). Then, they were glued together, back to back, into a single film strip. No special projector was needed.

The first publicly shown film using this process was The Toll of the Sea (1922) starring Anna May Wong. Perhaps the most ambitious all-Technicolor film was The Black Pirate (1926), starring and produced by Douglas Fairbanks.

In 1928, the system was improved. Dyes could be transferred from both color parts onto a single-sided print. This removed the need to glue two prints together and allowed many copies to be made from one set of color parts.

Technicolor's system was popular for years, but it was expensive. Filming cost three times as much as black-and-white, and printing was also much more expensive. By 1932, color photography was almost abandoned by major studios. But then Technicolor introduced a new process that recorded all three primary colors (red, green, and blue).

This new system used a special dichroic beam splitter and prisms. Light from the lens was split into two paths to expose three black-and-white films. Each film recorded the densities for red, green, or blue.

The three negatives were printed onto gelatin matrix films. These were processed to remove the silver, leaving only a gelatin relief of the images. A "receiver print" was made, which was a black-and-white print of the green component, including the soundtrack and frame lines. This print was treated to help it absorb dyes. The matrix for each color was soaked in its complementary dye (yellow, cyan, or magenta). Then, each matrix was pressed against the receiver print, which absorbed the dyes. This reproduced a nearly complete spectrum of color, unlike earlier two-color processes.

The first animated film to use the three-color system was Walt Disney's Flowers and Trees (1932), which audiences loved. The first short live-action film was La Cucaracha (1934), and the first all-color feature in "New Technicolor" was Becky Sharp (1935).

The rise of television in the early 1950s pushed the film industry to use more color. In 1947, only 12% of American films were in color. By 1954, that number was over 50%. This color boom was helped when Technicolor's near-monopoly on color film ended. Black-and-white films from major Hollywood studios mostly stopped being made in the mid-1960s. After that, color film became almost mandatory, with exceptions being rare.

Synchronized Sound

In July 1879, Fairman Rogers wrote about his and Thomas Eakins' experiments with Muybridge's horse pictures in a special zoetrope. He mentioned working on a system that would make a tapping sound when each horse's foot hit the ground.

Edison's phonograph made people more interested in recording motion pictures with sound. But when motion picture systems were developed, synchronizing sound turned out to be much harder than expected. Edison started showing the Kinetoscope without the expected sound. His 1895 Kinetophone version had earphones for sound from a phonograph hidden in the same cabinet, but the sound wasn't truly synchronized with the images.

However, there was still a lot of interest in making movies without sound. To improve the audience's experience, silent films were usually accompanied by live musicians, sometimes sound effects, or commentary from the showman. In most countries, intertitles (text on screen) were used to show dialogue and narration.

Inventors constantly experimented with sound film technology during the silent era. But the two main problems were accurate synchronization and making the sound loud enough. In 1926, Hollywood studio Warner Bros. introduced the "Vitaphone" system. They made short films of live acts and added recorded sound effects and music to some of their major movies.

In late 1927, Warners released The Jazz Singer. It was mostly silent but contained what is generally considered the first synchronized dialogue (and singing) in a feature film. Early sound-on-disc processes like Vitaphone were soon replaced by sound-on-film methods like Fox Movietone and RCA Photophone. This trend convinced the film industry that "talking pictures," or "talkies," were the future. Many attempts were made before The Jazz Singer succeeded.

Many improvements in sound recording and playback have been developed for movies, including stereophonic sound and surround sound (like Fantasound for Disney's Fantasia in 1940).

3D Movies

The popularity of 3D photography in the 1850s increased interest in creating a medium that would give a more complete illusion of reality by adding motion (and color). Although 3D was part of almost every attempt to record or display motion photography until the mid-1880s, the first important practical results were not 3D.

Several cinematic 3D systems were developed and sometimes even reached theaters during the first 50 years of cinema. But none had a big impact until anaglyphic films became popular for a while in the 1950s. 3D movie technology originally used two cameras filming the same thing. The content was then layered, and when wearing light-filtering glasses, the images seemed to pop off the screen. Interest in theatrical 3D movies decreased in later decades. However, they started to be used as special attractions, like 4D simulator rides and Imax theaters.

In the early 2000s, digital cinema began to take over, and polarized 3D movies became popular. Movies were no longer made on film. They were no longer shipped to theaters in film canisters, spliced together, and threaded through the projector. Instead, they were digitized and delivered on hard drives or via satellite. During this time, 3D films became very popular. Avatar was one of the first major 3D movies that changed 3D features. Avatar used 3D computer graphics (CG) and motion capture to make CG characters look real. This film combined real actors with CG characters to create an amazing world, making a visually stunning 3D show.

3D films are often seen as immersive experiences. They make the audience feel like they can reach out and touch what's on screen. With this new technology, most films were released in both standard 2D and 3D options. Cinemas everywhere started converting to fully digital systems so that 3D content could be shown in many theaters. For the experience to feel immersive, audience members need to feel like they are in the movie's world. Being present in this fantasy world is created not only by 3D technology but also by how well people connect with the story.

3D films are not for everyone. Some people get motion sickness and headaches while watching them. It's common for those who get migraines to trigger a headache during a 3D movie.

Creating immersive experiences isn't always easy. Not all 3D films are as captivating as Avatar or Gravity. It has become harder to create visually stunning films that truly take audiences on a journey. The 3D effects became less immersive and left audiences wondering if the film was "3D enough." Even though Hollywood marketed these as must-see attractions, the content sometimes felt forced, with movies being converted to 3D after they were filmed.

While live-action 3D films don't always succeed, 3D animation can always take new leaps with this technology. Animation can look really good and show audiences new visual technologies. Animators can take different risks, using their artistic skills and computer-generated worlds to create 3D spectacles for both children and adults.

3D films are not always made for 3D from the start. When they are converted later, the image on screen can be dull and not as bright as it should be. A normal reduction in light is expected because a 3D lens covers the projector lens, and moviegoers must wear 3D glasses. Knowing that light loss will happen, filmmakers should decide early if they want a film to be in 3D. This way, they can make necessary changes to avoid converting it later.

3D features require polarized 3D glasses so viewers can see the images in 3D. Many people find the glasses a hassle. It's not easy for those with prescription glasses to wear them, and it's hard for young children to keep them on. Simply touching the lens of the glasses can mess them up so you can no longer see the 3D images.

Automultiscopic display technology is a new film technology aiming to improve the moviegoing experience. Glasses would no longer be needed. Instead, multiple images from various angles would be displayed on screen. With this new technology, people would need to sit a certain distance from the screen, which could create challenges. Either way, new developments in 3D film technology could allow us to experience 3D in theaters without glasses.

While 3D features are not as popular as they once were, they still offer immersive experiences that amaze audiences. RealD 3D movies bring a realism to films, making it seem as though you are actually in the movie. Filmmakers and cinemas are still working on this technology, looking for new ways to create amazing experiences. Although audience interest declined after a few years, many cinemas still offer 3D screenings. Recently, technology has changed, giving moviegoers the chance to watch ScreenX films, where audiences are surrounded by the image. 4DX is also a popular new technology. It tries to provide incredibly immersive experiences, letting audience members smell scents, feel rain and wind, experience vibrations, and see car headlights flash across their face as if they are driving. Movies continue to adapt to ever-changing technologies.

4D Experiences

In 1962, Morton Heilig patented his Sensorama simulator. He built a prototype with a moving chair and 5 different stereoscopic films. Fans and odor emitters provided extra sensations. Heilig couldn't find money to develop this project further.

4D film has become a common theme park attraction since the 1980s. It also became a regular screening option for big action movies in more and more theaters after the 4DX technology was introduced in 2009.

Interactive Film and Virtual Reality

Coin-operated movie viewers like the Electrotachyscope, Kinetoscope, and Mutoscope were similar to other amusement arcade machines from the early 1900s. However, the machines that stayed popular in arcades were interactive games, while movies became much more popular in theaters. Even though movies and interactive games were mostly separate for the 20th century, some systems combined both. The digital revolution made video games start to look more like movies. Attempts to create theatrical interactive cinema, like I'm Your Man (1992), were less successful. Virtual reality is sometimes seen as a way to combine interactivity and cinema more effectively.

The idea of interactive film appeared soon after the cinematograph was invented. A technology for a shooting gallery with magic lantern or film projections was patented in 1901. An early successful example of cinematic shooting galleries appeared in the UK around 1912 called Life Targets. This type of game, often showing footage of safari animals, was popular in Great Britain for a short time.

Auto Test (1954) was an arcade driving training game. A player had to match their actions (gas pedal, brake, steering) to a first-person view film of a car ride projected on a small screen.

The early virtual reality system The Sword of Damocles was created in 1968. The view of 3D wireframe rooms changed based on mechanical head tracking.

In the 1970s and 1980s, virtual reality (VR) was mainly used in industrial, medical, and military training. In the 1990s, VR headsets became available for sale, mostly for video games. VR has been increasingly used for cinematic experiences, even having its own section at the Venice Film Festival since 2017.

Widescreen and 360° Film

Since different people developed film systems independently, frame sizes and projection ratios varied. However, 35mm movie film became standard early on. The 1.37:1 Academy ratio became a standard in the 1930s.

After television became popular, widescreen movies became a popular way to keep theatrical movies more interesting starting in the 1950s. Anamorphic formats were developed to allow filming for widescreen formats on standard 35mm film.

Screen projections that surrounded the audience were developed by Disney as a Disneyland attraction called Circarama in 1955. It was replaced by Circle-Vision 360° a few years later.

360-degree video became common after YouTube and Facebook added support for publishing and viewing them on their platforms in 2015.

Digital Film

Digital cinematography, which means capturing film images using digital image sensors instead of film stock, has largely replaced older analog film technology. As digital technology has improved, this method has become dominant. Since the mid-2010s, most movies worldwide are captured and distributed digitally.

Many companies have created products, including traditional film camera makers like Arri and Panavision. New companies like RED, Blackmagic, and Silicon Imaging have also joined. Companies that used to focus on consumer and broadcast video equipment, like Sony, GoPro, and Panasonic, are also making digital film cameras.

Current digital film cameras with 4K output are roughly equal to 35mm film in their resolution and dynamic range. However, digital film still looks slightly different from analog film. Some filmmakers and photographers still prefer to use analog film to get the look they want.

Digital cinema, which uses digital technology to distribute or project motion pictures, has also largely replaced the old way of using reels of motion picture film, like 35mm film. Traditional film reels had to be shipped to movie theaters. Now, a digital movie can be sent to cinemas in several ways: over the Internet, through special satellite links, or by sending hard drives or optical discs like Blu-ray discs. Digital movies are projected using a digital projector instead of a traditional film projector. Digital cinema is different from high-definition television and does not rely on TV or high-definition video standards, aspect ratios, or frame rates. In digital cinema, resolutions are shown by the horizontal pixel count, usually 2K (2048×1080 pixels) or 4K (4096×2160 pixels). As digital cinema technology improved in the early 2010s, most theaters worldwide converted to digital.

|

See also

- List of cinematic firsts

- List of color film systems

- List of motion picture film formats

- Newsreel

- Silent film

- Sound film

- The Story of Film: An Odyssey, 2011 documentary

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |