Thomas Eakins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Eakins

|

|

|---|---|

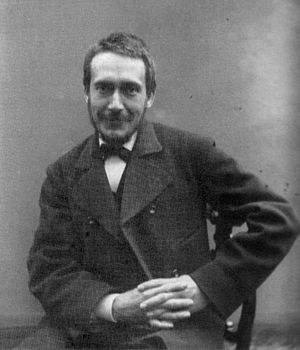

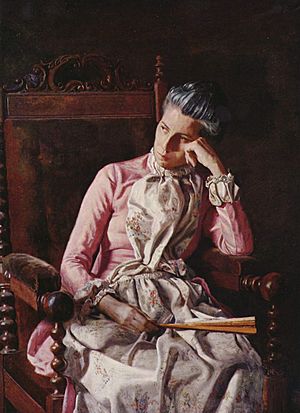

Self portrait (1902)

National Academy of Design, New York |

|

| Born |

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins

July 25, 1844 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

|

| Died | June 25, 1916 (aged 71) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

|

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

|

Notable work

|

Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, 1871 The Gross Clinic, 1875 The Agnew Clinic, 1889 William Rush and His Model, 1908 |

| Movement | Realism |

| Awards | National Academician |

Thomas Eakins (July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American realist painter, photographer, sculptor, and art teacher. Many people consider him one of the most important American artists.

For about 40 years, from the 1870s until his health declined, Eakins painted real life. He chose people from his hometown of Philadelphia as his subjects. He painted hundreds of portraits, often of friends, family, or important people in art, science, medicine, and religion. Together, these portraits show a picture of intellectual life in Philadelphia at that time. Each portrait also gives a clear look at the person's thoughts and feelings.

Eakins also created large paintings that showed people outside. He painted them in offices, on streets, in parks, on rivers, in sports arenas, and even in surgical rooms. These outdoor scenes allowed him to paint what he loved most: people moving, often with light clothing. This way, he could show the body's shapes in sunlight and create scenes with deep space using his knowledge of perspective. Eakins was also very interested in new technologies like motion photography, where he was an innovator.

His work as a teacher was also very important. He greatly influenced American art through his teaching. However, he faced difficulties as an artist trying to paint realistically. These problems were even bigger in his teaching career, where controversies cut short his success and harmed his reputation.

Eakins was a controversial figure. His work did not get much official praise during his lifetime. But since his death, art historians have celebrated him. They call him "the strongest, most profound realist in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American art."

Contents

Thomas Eakins: A Life in Art

Early Life and Education

Thomas Eakins was born and lived most of his life in Philadelphia. He was the first child of Caroline Cowperthwait Eakins and Benjamin Eakins. His father was a writing and calligraphy teacher. Thomas watched his father work. By age twelve, he was skilled at precise line drawing and using grids for design. He later used these skills in his art.

He was an athletic child who loved rowing, ice skating, swimming, wrestling, sailing, and gymnastics. He later painted these activities and encouraged his students to do them. Eakins went to Central High School, a top public school for science and arts. He was excellent at mechanical drawing. He met his lifelong friend, artist Charles Lewis Fussell, there. They later studied together at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Thomas started at the academy in 1861. He also took anatomy and dissection classes at Jefferson Medical College from 1864 to 1865. For a time, he worked as a "writing teacher," like his father. His interest in the human body even made him think about becoming a surgeon.

From 1866 to 1870, Eakins studied art in Europe. He notably studied in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, a French realist painter. He also attended the studio of Léon Bonnat, another realist who focused on exact anatomy. Eakins adopted this method. While at the École des Beaux-Arts, he wasn't interested in the new Impressionist movement. He also didn't like what he saw as the fancy style of the French Academy. In a letter home in 1868, he clearly stated his artistic view. He said he hated "affectation" and wanted to paint things as they truly were.

A six-month trip to Spain confirmed his admiration for realist artists like Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera. In Seville in 1869, he painted Carmelita Requeña, a portrait of a seven-year-old gypsy dancer. It was painted more freely and colorfully than his Paris studies. That same year, he tried his first large oil painting, A Street Scene in Seville. Here, he dealt with the challenges of painting a scene outside the studio. Even though he didn't get a formal degree or show works in European art shows, Eakins learned techniques from French and Spanish masters. He began to form his artistic vision, which he showed in his first major painting after returning to America. He declared, "I shall seek to achieve my broad effect from the very beginning."

Early Career and Sports Paintings

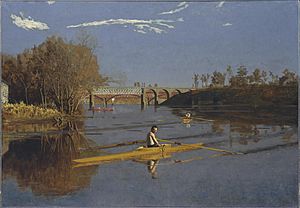

When Eakins returned from Europe, his first works included many rowing scenes. There were eleven oil paintings and watercolors. The first and most famous is Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871). Both his subject and his painting style drew attention. Choosing a modern sport was "a shock to the artistic conventionalities of the city." Eakins even put himself in the painting, in a scull behind Schmitt. His name is written on the boat.

To create this work, Eakins carefully observed the subject. He made drawings of the figures and plans for the scull in the water. This preparation shows how important his art training in Paris was. It was a completely new idea, based on Eakins' own experience. It was a surprisingly successful painting for an artist who had struggled with his first outdoor scene less than a year before. His first known sale was the watercolor The Sculler (1874). Most critics thought his rowing pictures were good and promising. But after this initial success, Eakins never painted rowing again. He moved on to other sports themes.

At the same time, Eakins painted a series of indoor scenes. These often featured his father, sisters, or friends. Home Scene (1871), Elizabeth at the Piano (1875), The Chess Players (1876), and Elizabeth Crowell and her Dog (1874) are examples. These paintings are dark in color. They focus on showing people naturally in their homes, without being overly emotional.

In 1872, he painted his first large portrait, Kathrin. In it, Kathrin Crowell is seen in dim light, playing with a kitten. In 1874, Eakins and Crowell became engaged. She died of meningitis in 1879, while they were still engaged.

Teaching and Controversy

Eakins returned to the Pennsylvania Academy to teach in 1876. He started as a volunteer after the school's new building opened. He became a paid professor in 1878 and director in 1882. His teaching methods were different from others. He didn't have students draw from old statues. Instead, students quickly moved from charcoal drawing to painting. This helped them understand subjects in their true colors. He encouraged students to use photography to learn about anatomy and how things move. He also didn't allow prize competitions. Students who wanted to use their art skills for things like illustration or decoration were welcome, just like those who wanted to be portrait artists.

Most importantly, he taught all parts of the human figure. This included studying human and animal bodies, and even surgical dissection. There were also tough classes on basic shapes and perspective, which involved math. To help with anatomy, plaster models were made from dissections and given to students. He also studied horse anatomy. In 1891, his friend, sculptor William Rudolf O'Donovan, asked Eakins to help him. They worked together to create bronze horse reliefs of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant for an arch in Brooklyn.

Because Eakins believed in learning from real life, the academy's art program was very advanced by the early 1880s. Eakins believed in teaching by showing examples. He let students find their own way with only short advice. His students included painters, cartoonists, and illustrators like Henry Ossawa Tanner and Thomas Pollock Anshutz.

He said his teaching idea simply: "A teacher can do very little for a pupil & should only be thankful if he don't hinder him ... and the greater the master, mostly the less he can say." He believed women should have the same professional chances as men. Classes with live models and dissections were separate for men and women. But women had access to male models (who wore loincloths).

However, his teaching methods sometimes caused problems. He was forced to resign in 1886. This happened because of controversial teaching methods related to studying the human body in class, which caused tension with the academy's board.

This forced resignation was a big setback for Eakins. His family was divided, with some relatives speaking against him. He struggled to protect his name from rumors. He had periods of illness and felt humiliated for the rest of his life. A drawing manual he had written was never finished or published during his lifetime. Many students supported Eakins. Some left the academy and formed the Art Students' League of Philadelphia (1886–1893), where Eakins continued to teach. There, he met Samuel Murray, who became his student and lifelong friend. He also taught at other schools, including the Art Students League of New York. He gradually stopped teaching by 1898.

Photography and Art

Eakins is known for bringing the camera into American art studios. While studying in Europe, he saw how French realists used photography. However, traditional artists often thought using photos was a shortcut.

In the late 1870s, Eakins learned about the motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge. He was especially interested in Muybridge's photos of horses moving. Eakins became interested in using the camera to study how things move in sequence. In 1883, Muybridge gave a lecture at the academy, arranged by Eakins. In 1884, Eakins worked briefly with Muybridge in his photo studio in Philadelphia.

Eakins soon did his own motion studies. He even developed his own way to capture movement on film. Muybridge used many cameras to take a series of individual photos. Eakins preferred to use one camera to take many exposures on a single negative. Eakins wanted precise measurements from one image to help him paint motion. Muybridge wanted separate images that could be shown with his early movie projector.

After Eakins got a camera in 1880, he used photographs for several paintings. For example, Mending the Net (1881) and Arcadia (1883) were partly based on his photos. Some figures in his paintings look like they were carefully traced from photographs. Eakins then worked hard to cover these traces with oil paint. His methods were very careful. He used photos not as shortcuts, but to achieve accuracy and realism.

A great example of Eakins using this new technology is his painting A May Morning in the Park. He used photographic motion studies to show the true way the four horses pulled the coach. But Eakins also used wax figures and oil sketches to get the final look he wanted.

Starting in 1883, Eakins took photo series of students and professional models. These photos showed real human anatomy from different angles. They were often displayed at the school for study. Later, he took less formal photos, indoors and outdoors, of men, women, and children, including his wife. Some photos showed Eakins with a female model. Even though chaperones were usually present, and the poses were mostly traditional, the large number of photos and Eakins' open display of them may have hurt his reputation at the academy. In total, about eight hundred photographs are now linked to Eakins and his group. Most are studies of figures and portraits. No other American artist of his time was as interested in photography or created as many photographic works.

Famous Portraits

Eakins once said, "I will never have to give up painting, for even now I could paint heads good enough to make a living anywhere in America."

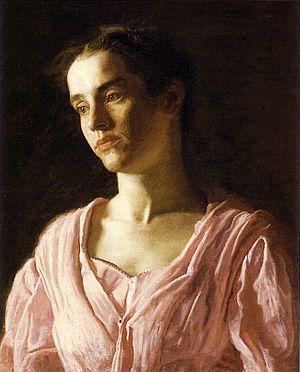

For Eakins, painting portraits was not about making people look ideally beautiful or just exactly like they were. Instead, it was a chance to show a person's true character by painting their solid body shape. This meant Eakins would never be a very successful portrait painter who got many paid jobs. But his total of about 250 portraits shows his "uncompromising search for the unique human being."

Often, to find this individuality, he painted people in their everyday work environments. Eakins' Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand (1874) was a step towards what many consider his most important work.

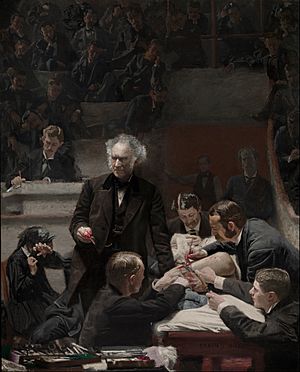

In The Gross Clinic (1875), a famous Philadelphia surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, is shown leading an operation. He is removing part of a diseased bone from a patient's thigh. Gross is lecturing in a crowded amphitheater at Jefferson Medical College. Eakins spent almost a year on this painting. He chose a new subject: modern surgery, which Philadelphia was leading in. He started the project hoping it would be a grand work for the Centennial Exposition of 1876. The painting was rejected from the main Art Gallery. It was shown instead at a U.S. Army Post Hospital exhibit on the centennial grounds. In contrast, another Eakins painting, The Chess Players, was accepted and praised at the Centennial Exhibition.

At 96 by 78 inches (240 × 200 cm), The Gross Clinic is one of Eakins' largest works. Some consider it his greatest. Eakins had high hopes for it. He wrote in a letter, "What elates me more is that I have just got a new picture blocked in and it is very far better than anything I have ever done." But if Eakins hoped to impress his hometown, he was disappointed. Public reaction to the realistic surgical cut and blood was mixed. The college bought it for only $200. Eakins borrowed it for later exhibitions, where it caused strong reactions. The New York Daily Tribune praised its power but also said it shouldn't be in a gallery where people with "weak nerves" had to see it. Today, the college describes it as "a great nineteenth-century medical history painting, featuring one of the most superb portraits in American art."

In 1876, Eakins finished a portrait of Dr. John Brinton, a surgeon famous for his Civil War service. This painting was done in a more relaxed setting than The Gross Clinic. Eakins personally liked it a lot. The Art Journal said it was a better example of his skill than his "much-talked-of composition representing a dissecting room."

Other great portraits include The Agnew Clinic (1889), Eakins' most important commission and largest painting. It shows another famous American surgeon, Dr. David Hayes Agnew, performing a mastectomy. The Dean's Roll Call (1899) and Professor Leslie W. Miller (1901) are portraits of educators standing as if speaking to an audience. A portrait of Frank Hamilton Cushing (around 1895) shows the ethnologist performing a ritual. Professor Henry A. Rowland (1897) shows a brilliant scientist. Antiquated Music (1900) shows Mrs. William D. Frishmuth among her musical instruments. For The Concert Singer (1890–1892), Eakins asked Weda Cook to sing so he could study her throat and mouth muscles. To paint a baton correctly, Eakins had an orchestra conductor pose for the hand in the painting's lower left corner.

Many of Eakins' later portraits were of women who were friends or students. Unlike most paintings of women at the time, these portraits don't make them look overly glamorous or perfect. For Portrait of Letitia Wilson Jordan (1888), Eakins painted her in the same evening dress he saw her wearing at a party. She looks strong and real, very different from the popular portraits of the era. Similarly, his Portrait of Maud Cook (1895) shows the subject's beauty with "a stark objectivity."

The portrait of Miss Amelia Van Buren (around 1890), a friend and former student, suggests a complex and thoughtful person. It has been called "the finest of all American portraits." Even Susan Macdowell Eakins, a talented painter and former student who married Eakins in 1884, was not made to look overly sweet. Despite its rich colors, The Artist's Wife and His Setter Dog (around 1884–1889) is a very honest portrait.

Some of his most striking portraits came from a later series he did for Catholic clergy. These included paintings of a cardinal, archbishops, bishops, and monsignors. Most of these people posed at Eakins' request and were given the portraits when he finished them. In portraits like His Eminence Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli (1902) and Archbishop William Henry Elder (1903), Eakins used the bright robes to make the paintings lively. This wasn't possible in his other male portraits.

After being dismissed from the academy, Eakins focused his later career on portraits, such as his 1905 Portrait of Professor William S. Forbes. His strong belief in his own realistic style, along with the scandals from his teaching, hurt his income in later years. Even though he painted these portraits with the skill of a highly trained anatomist, what stands out most is the intense feeling of his subjects. However, this was also why his portraits were often rejected by the people he painted or their families. So, Eakins had to rely on friends and family to pose for him. His portrait of Walt Whitman (1887–1888) was the poet's favorite.

The Human Figure in Art

Eakins' lifelong interest in the human figure appeared in several themes. The rowing paintings of the early 1870s were his first series of figure studies. In Eakins' largest painting on this subject, The Biglin Brothers Turning the Stake (1873), the strong muscles and movement of the body are shown in full detail.

In the 1877 painting William Rush and His Model, he painted a female figure as part of a historical scene. The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 helped bring back interest in Colonial America. Eakins took part with a big project using oil studies, wax, and wood models, and finally the portrait in 1877. William Rush was a famous Colonial sculptor and ship carver. He was a respected artist and citizen in Philadelphia and helped found the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where Eakins had started teaching.

Despite his clear respect for Rush, Eakins' way of showing the human body again drew criticism. This time, people were unhappy because the model and her piled-up clothes were shown clearly in the front. Rush was placed in the deep shadows in the left background. Still, Eakins found a subject that connected to his city and an earlier Philadelphia artist. It also allowed him to study the female figure from behind.

When he returned to this subject many years later, the story became more personal. In William Rush and His Model (1908), the chaperone and detailed room of the earlier work are gone. The professional distance between the sculptor and model is removed, and their relationship seems more private.

The Swimming Hole (1884–85) shows Eakins' best studies in his most successful outdoor painting. The figures are his friends and students, and one is a self-portrait. Although Eakins took photographs related to the painting, the picture's strong pyramid shape and sculptural way of showing each body are unique artistic choices. The work was painted for a client but was refused.

In the late 1890s, Eakins returned to painting male figures, this time in a city setting. Taking the Count (1896), a painting of a prizefight, was his second largest canvas. However, it wasn't his most successful composition. The same can be said for Wrestlers (1899). More successful was Between Rounds (1899). For this, boxer Billy Smith posed sitting in his corner at Philadelphia's Arena. In fact, all the main figures were posed by models acting out a real fight. Salutat (1898), a painting that looks like a long, narrow carving, with the main figure standing alone, "is one of Eakins' finest achievements in figure-painting."

Even though Eakins was agnostic (meaning he wasn't sure about God), he painted The Crucifixion in 1880. Art historian Akela Reason noted that some art historians found this surprising. They thought Eakins painted it just to show realism, not for religious reasons. For example, Lloyd Goodrich thought it had no "religious sentiment" and was just a realistic study of the male body. Because of this, art historians often connect Crucifixion with Eakins' strong interest in anatomy.

Personal Life and Marriage

In 1884, at age 40, Eakins married Susan Hannah Macdowell. She was the daughter of a Philadelphia engraver. Two years earlier, Eakins' sister Margaret, who had helped him as a secretary, died. Some suggest Eakins married to have someone to help him. Macdowell was 25 when she met Eakins in 1875. She was impressed by The Gross Clinic and decided to study with him at the academy. She attended for six years and developed a serious, realistic style like his. Macdowell was an excellent student and won an award for the best painting by a female artist.

During their marriage, they had no children. Susan painted only sometimes. She spent most of her time supporting her husband's career, hosting guests and students. She faithfully stood by him during his difficult times with the academy, even when some of her family disagreed with Eakins. Both she and Eakins loved photography, both taking photos and being subjects. They used it as a tool for their art. They both had separate studios in their home. After Eakins died in 1916, she returned to painting. She painted much more until the 1930s, in a style that became warmer and brighter. She died in 1938. Thirty-five years after her death, in 1973, she had her first solo art show at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Later Life and Legacy

Eakins died on June 25, 1916, at age 71. He is buried at The Woodlands in West Philadelphia.

Late in his life, Eakins did receive some recognition. In 1902, he became a National Academician. In 1914, a portrait study of D. Hayes Agnew for The Agnew Clinic was sold. Rumors spread that it sold for fifty thousand dollars, causing much publicity. In reality, it sold for four thousand dollars.

The year after he died, Eakins was honored with a special exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1917–18, the Pennsylvania Academy did the same. Susan Macdowell Eakins worked hard to keep his reputation alive. She gave the Philadelphia Museum of Art over fifty of her husband's oil paintings. After her death in 1938, other works were sold or damaged. Later, a large collection of his art and personal items was bought by Joseph Hirshhorn. It is now part of the Hirshhorn Museum. Since then, Eakins' home in North Philadelphia was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. Eakins Oval, across from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was named after him. In 1967, The Biglin Brothers Racing (1872) was put on a United States postage stamp. His work was also part of the painting event at the 1932 Summer Olympics.

Eakins' approach to realism in painting and his desire to explore American life were very influential. He taught hundreds of students, including his future wife Susan Macdowell and African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner. His student Thomas Pollock Anshutz later taught artists like Robert Henri and John French Sloan, who became members of the Ashcan School. These artists continued Eakins' realistic style. Even though Eakins is not a household name and struggled financially during his life, today he is seen as one of the most important American artists ever.

Controversy shaped much of his career as a teacher and artist. He insisted on teaching men and women "the same" way. He was accused of improper behavior with female students.

Recent studies suggest these scandals were not just because people were overly strict at the time. They may have been caused by a mix of factors. These include Eakins' unconventional lifestyle, his intense teaching style, and his tendency for unusual or provocative behavior.

What Happened to His Art?

Eakins could not sell many of his paintings during his lifetime. So, when he died in 1916, a large amount of his artwork went to his widow, Susan Macdowell Eakins. She carefully protected it, giving some of the best pieces to various museums. When she died in 1938, much of the remaining art was unfortunately destroyed or damaged by those handling her estate. What was left was later saved by a former Eakins student. You can find more details in the article "List of works by Thomas Eakins".

On November 11, 2006, the board of trustees at Thomas Jefferson University agreed to sell The Gross Clinic. It was to be sold to the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. The price was a record $68,000,000. This was the highest price for an Eakins painting and a record for an American portrait. On December 21, 2006, a group of donors matched the price to keep the painting in Philadelphia. It is now shown alternately at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

How Eakins is Remembered

On October 29, 1917, artist Robert Henri wrote an open letter about Eakins to the Art Students League:

Thomas Eakins was a man of great character. He had a strong will to paint and live his life as he thought it should be. He did this. It cost him a lot, but in his works, we have the valuable result of his independence, his generous heart, and his big mind. Eakins deeply studied life, and with great love, he openly studied people. He was not afraid of what he learned.

When it came to how to express himself, the science of technique, he studied very deeply, as only a great master would have the will to study. His artistic vision was not affected by trends. He worked to understand the building forces in nature and to use those principles in his art. His main quality was honesty. "Integrity" seems to fit him best. Personally, I think he is the greatest portrait painter America has produced.

In 1982, in his two-volume Eakins biography, art historian Lloyd Goodrich wrote:

Despite his limits—and what artist is free of them?—Eakins' achievement was huge. He was our first major painter to fully accept the realities of modern city America, and from them to create powerful, deep art... In portraiture alone, Eakins was the strongest American painter since Copley, with equal substance and power, and added insight, depth, and subtlety.

John Canaday, art critic for The New York Times, wrote in 1964:

As a supreme realist, Eakins seemed heavy and ordinary to a public that thought of art and culture mostly as graceful sentimentality. Today, we feel he captured his fellow Americans with a sensitivity that was often as gentle as it was strong. He preserved for us the essence of an American life which, indeed, he did not make perfect—because it seemed beautiful to him without needing to be made perfect.

In 2010, American painter Philip Pearlstein wrote an article. He suggested that Eadweard Muybridge's work and lectures greatly influenced 20th-century artists. These included Degas, Rodin, Seurat, Duchamp, and Eakins. This influence came either directly or through the work of another photography pioneer, Étienne-Jules Marey. Pearlstein concluded:

I believe that both Muybridge and Eakins—as a photographer—should be recognized as among the most influential artists on the ideas of 20th-century art, along with Cézanne, whose lessons in fractured vision provided the technical basis for putting those ideas together.

|

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Eakins para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Eakins para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |