Anna May Wong facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anna May Wong

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Publicity photo of Anna May Wong from Stars of the Photoplay, 1930

|

|||||||||||||||||

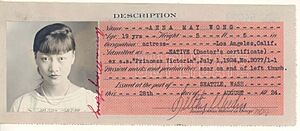

| Born |

Wong Liu Tsong

January 3, 1905 Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

||||||||||||||||

| Died | February 3, 1961 (aged 56) Santa Monica, California, U.S.

|

||||||||||||||||

| Occupation | Actress | ||||||||||||||||

| Years active | 1919–1961 | ||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Hollywood Walk of Fame – Motion Picture 1700 Vine Street |

||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃柳霜 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄柳霜 | ||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

Anna May Wong (born Wong Liu Tsong; January 3, 1905 – February 3, 1961) was an American actress. She is known as the first Chinese American film star in Hollywood. She was also the first Chinese American actress to become famous around the world. Her career included silent films, movies with sound, television shows, stage plays, and radio.

Anna May Wong was born in Los Angeles to Chinese American parents. She loved movies and decided at age 11 to become an actress. Her first role was a small part in The Red Lantern (1919). During the silent film era, she starred in The Toll of the Sea (1922), one of the first color films. She also appeared in Douglas Fairbanks' The Thief of Bagdad (1924). By 1924, Wong was a fashion icon and famous worldwide. She was one of the first to try the "flapper" style. In 1934, she was voted the "world's best dressed woman."

Wong often felt frustrated by the limited roles she was offered in Hollywood. These roles were often stereotypical and not very interesting. In 1928, she moved to Europe, where she acted in many plays and films, like Piccadilly (1929). In the early 1930s, she traveled between the U.S. and Europe for work. She appeared in early sound films such as Daughter of the Dragon (1931), Shanghai Express (1932) with Marlene Dietrich, Java Head (1934), and Daughter of Shanghai (1937).

In 1935, Wong faced a big disappointment. She wanted the main Chinese role of O-lan in the movie The Good Earth. However, the studio chose a white actress, Luise Rainer, to play the part. This was a common practice called "yellowface". Wong was offered a smaller, less positive role, but she refused it.

After this, Wong spent a year traveling in China. She visited her family's village and learned more about Chinese culture. In the late 1930s, she made several films for Paramount Pictures. In these movies, she played Chinese and Chinese American characters in a positive way. During World War II, she spent less time on films. Instead, she helped the Chinese cause against Japan. In the 1950s, Wong returned to acting in several television shows.

In 1951, Wong made history with her TV show The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong. It was the first U.S. television show to star an Asian American lead actress. She planned to return to film in Flower Drum Song but died in 1961 at age 56 from a heart attack. For many years after her death, people mostly remembered Wong for the stereotypical "Dragon Lady" and "Butterfly" roles she often played. However, around the 100th anniversary of her birth, her life and career were re-examined and celebrated.

Contents

- Biography: Anna May Wong's Life Story

- Early Life: A Star is Born

- Early Career: Breaking into Movies

- Stardom: Becoming a Recognized Face

- Move to Europe: New Opportunities Abroad

- Return to Hollywood: A New Chapter

- Atlantic Crossings: Seeking Better Roles

- Chinese Tour and Later Films

- Later Years: Television and Legacy

- Later Life and Death: A Lasting Impact

- Legacy: Remembering Anna May Wong

- Partial Filmography: Movies and TV Shows

- Images for kids

- See also

Biography: Anna May Wong's Life Story

Early Life: A Star is Born

Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong on January 3, 1905. She grew up on Flower Street in Los Angeles, near Chinatown. Her neighborhood was a mix of Chinese, Irish, German, and Japanese families. She was the second of seven children born to Wong Sam-sing, who owned a laundry, and his second wife, Lee Gon-toy.

Anna May's parents were second-generation Chinese Americans. This means their parents had come to the U.S. earlier. Her paternal grandfather, A Wong Wong, was a merchant who arrived in 1853. Anna May's father traveled between the U.S. and China. In 1901, he married Anna May's mother. Anna May had an older sister, Lulu, and six younger siblings.

In 1910, her family moved to Figueroa Street. They were the only Chinese family on their block. Anna May went to public school at first. But when other students made fun of her because of her race, she moved to a Presbyterian Chinese school. She also attended a Chinese-language school in the afternoons and on Saturdays.

Around this time, movie studios started moving to Los Angeles. Movies were often filmed near Wong's home. She loved going to nickelodeon theaters and became obsessed with movies. She would skip school and use her lunch money to see films. Her father worried it would affect her studies, but Anna May was determined to become an actress. At age nine, she often asked filmmakers for roles, earning her the nickname "C.C.C." or "Curious Chinese Child." By age 11, she chose her stage name, Anna May Wong, combining her English and family names.

Early Career: Breaking into Movies

Wong was working at a department store when a movie studio needed 300 female extras for The Red Lantern (1919). Without her father knowing, a friend helped her get a small, uncredited role. She carried a lantern in the film.

For the next two years, Wong worked as an extra in various movies. While still a student, she became ill and missed months of school. She eventually recovered. In 1921, Wong decided to leave Los Angeles High School to act full-time. She told Motion Picture Magazine in 1931, "I was so young when I began that I knew I still had youth if I failed, so I determined to give myself 10 years to succeed as an actress."

In 1921, Wong got her first screen credit in Bits of Life. She played the wife of Lon Chaney's character. She later remembered it as her only role as a mother. Her appearance earned her a cover photo on a British magazine.

At age 17, Wong played her first main role in The Toll of the Sea. This early film used two-color Technicolor. The story was similar to Madama Butterfly. Variety magazine praised Wong's "extraordinarily fine" acting. The New York Times said she had a "difficult role" but gave a "tenth performance." They noted she was "completely unconscious of the camera" and had "remarkable pantomimic accuracy."

Despite these good reviews, Hollywood was slow to give Wong starring roles. Her Chinese background made filmmakers see her as "exotic" rather than a leading lady. She spent the next few years in supporting roles. She often played characters that added "exotic atmosphere," like a concubine in Drifting (1923). Film producers used her growing fame but kept her in smaller parts. Still hopeful, Wong said in 1923, "Pictures are fine and I'm getting along all right."

Stardom: Becoming a Recognized Face

At 19, Wong played a clever Mongol slave in Douglas Fairbanks' 1924 film The Thief of Bagdad. Even though her appearances were short, she caught the attention of audiences and critics. The film made over $2 million and helped make Wong famous. Around this time, Wong moved out of her family home. She knew Americans saw her as "foreign-born," even though she was from California. So, she started to create a modern, "flapper" image. In 1924, she tried to start her own film company, Anna May Wong Productions, but it did not work out.

It became clear that Wong's career was limited by rules in American films. These rules often prevented her from having romantic scenes with actors of other races. Unless Asian leading men could be found, Wong could not be a main romantic lead.

Wong continued to be offered "exotic" supporting roles. She played native girls in two 1924 films. She was an Eskimo in The Alaskan and Princess Tiger Lily in Peter Pan. Peter Pan was a big hit. The next year, Wong received praise for playing a manipulative "Oriental vamp" in Forty Winks. Despite good reviews, she was unhappy with her roles and looked for other ways to succeed.

In 1926, Wong helped with the groundbreaking ceremony for Grauman's Chinese Theatre. She put in the first rivet and turned the first spadeful of earth with Norma Talmadge. However, she was not invited to leave her handprints or footprints in the cement. That same year, Wong starred in The Silk Bouquet, later called The Dragon Horse. This was one of the first U.S. films made with Chinese funding. It was set in China during the Ming dynasty and featured Asian actors in Asian roles.

Wong kept getting supporting roles. Hollywood's Asian female characters were usually either the innocent "Butterfly" or the sneaky "Dragon Lady." In Old San Francisco (1927), Wong played a "Dragon Lady," a gangster's daughter. In Mr. Wu (1927) and The Crimson City (1928), she also played supporting parts.

Move to Europe: New Opportunities Abroad

Tired of being typecast and losing lead roles to non-Asian actresses, Wong left Hollywood in 1928 for Europe. In a 1933 interview, Wong said, "I was so tired of the parts I had to play." She added, "There seems little for me in Hollywood, because, rather than real Chinese, producers prefer Hungarians, Mexicans, American Indians for Chinese roles."

In Europe, Wong became very popular. She starred in films like Schmutziges Geld (1928), Großstadtschmetterling (Pavement Butterfly, 1929), and Der Weg zur Schande (The Road to Dishonour, 1930). German critics praised her as a "transcendent talent" and a "great beauty." In Vienna, she performed in the play Tschun Tschi in fluent German. An Austrian critic said she had the audience "perfectly in her power."

While in Germany, Wong became friends with Leni Riefenstahl, who was an actress at the time. Wong's close friendships with several women, including Marlene Dietrich, led to rumors about her personal life. These rumors caused embarrassment for her family, who already did not approve of her acting career.

London producer Basil Dean brought the play A Circle of Chalk for Wong to star in with a young Laurence Olivier. This was her first stage performance in the United Kingdom. Critics noted her "Yankee squeak" accent, so Wong took voice lessons at Cambridge University. Composer Constant Lambert was so impressed by her that he dedicated his Eight Poems of Li Po to her.

Wong made her last silent film, Piccadilly, in 1929. This was the first of five British films where she had a starring role. The film was a big hit in the UK. Variety magazine said Wong "outshines the star" and "steals 'Piccadilly'." For decades, this film was forgotten, but it was later restored. Time magazine's Richard Corliss called Piccadilly Wong's best film. Its rediscovery helped restore her reputation.

Wong's first talkie (movie with sound) was The Flame of Love (1930). She recorded it in French, English, and German. Her performance and language skills were praised, even though the film itself received negative reviews.

Return to Hollywood: A New Chapter

In the 1930s, American studios looked for new European talent. Wong caught their eye, and Paramount Studios offered her a contract in 1930. She was promised lead roles and top billing, so she returned to the United States. Her experience in Europe led to a starring role on Broadway in On the Spot. This play ran for 167 performances. When the play's director wanted Wong to use Japanese mannerisms for her Chinese character, Wong refused. She used her knowledge of Chinese culture to make the character more real. After returning to Hollywood, Wong often turned to stage and cabaret performances for creative expression.

In November 1930, Wong's mother died after being hit by a car. The family stayed in their home until 1934. Then, Wong's father returned to his hometown in China with her younger brothers and sister. Anna May had been paying for her siblings' education. Before they left, her father wrote an article expressing pride in his famous daughter.

Wong accepted another stereotypical role in Daughter of the Dragon (1931). She played the vengeful daughter of Fu Manchu. This was her last "evil Chinese" role. It was also her only starring role with Sessue Hayakawa, another well-known Asian actor of that time. Even though she was the star, she was paid less than her co-stars.

Wong started using her fame to speak out. In 1931, she criticized Japan's invasion of Manchuria. She also spoke up for Chinese American causes and better film roles. In a 1933 interview, Wong criticized the negative stereotypes in Daughter of the Dragon. She asked, "Why is it that the screen Chinese is always the villain? ... We are not like that. How could we be, with a civilization that is so many times older than the West?"

Wong appeared with Marlene Dietrich in Sternberg's Shanghai Express. Many film historians today believe Wong's performance was stronger than Dietrich's.

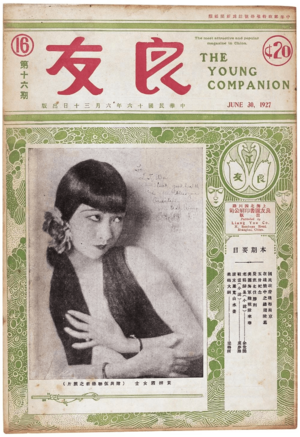

The Chinese press had mixed feelings about Wong's career. Some criticized her performance in Shanghai Express, saying she "disgraced the Chinese race." However, in 1932, Peking University gave her an honorary doctorate. This was very rare for an actor.

In both America and Europe, Wong was a fashion icon for over ten years. In 1934, she was voted "The World's best-dressed woman." In 1938, Look magazine called her "The World's most beautiful Chinese girl."

Atlantic Crossings: Seeking Better Roles

After her success in Europe and Shanghai Express, Wong's Hollywood career went back to old patterns. She was passed over for lead roles in films like The Son-Daughter and The Bitter Tea of General Yen. Studios thought she was "too Chinese to play a Chinese" in some films.

Disappointed again, Wong returned to Britain for almost three years. She made four films and toured Scotland and Ireland in a vaudeville show. She also appeared in the King George Silver Jubilee program in 1935. Her film Java Head (1934) was the only film where Wong kissed the main male character, her white husband in the movie. This might be why it was one of her favorites. While in London, Wong met Mei Lanfang, a famous star of the Beijing Opera. Mei offered to teach Wong if she visited China.

In the 1930s, Pearl Buck's novels, like The Good Earth, became popular. Also, Americans felt more sympathy for China because of its struggles with Japan. This created chances for more positive Chinese roles in U.S. films. Wong returned to the U.S. in 1935, hoping to play O-lan in MGM's film of The Good Earth. She had wanted this role since the book came out in 1931.

However, the studio never seriously considered Wong for the part. The Chinese government also advised against casting her. They said, "whenever she appears in a movie, the newspapers print her picture with the caption 'Anna May again loses face for China'."

Wong said she was offered the role of Lotus, a tricky character who helps ruin the family. Wong refused, telling MGM's head, "If you let me play O-lan, I will be very glad. But you're asking me—with Chinese blood—to do the only unsympathetic role in the picture featuring an all-American cast portraying Chinese characters."

The role Wong wanted went to Luise Rainer, who won an Oscar for it. Wong's sister, Mary Liu Heung Wong, played a small role in the film. MGM's refusal to cast Wong in this important Chinese role is remembered as a major example of unfair casting in the 1930s.

Chinese Tour and Later Films

After losing the role in The Good Earth, Wong planned a year-long trip to China. She wanted to visit her father and his family. Her father had returned to China in 1934. She also wanted to learn more about Chinese theater. She told a newspaper, "... for a year, I shall study the land of my fathers."

Starting in January 1936, Wong wrote about her trip in U.S. newspapers. In Tokyo, reporters asked if she planned to marry. Wong replied, "No, I am wedded to my art." The next day, Japanese newspapers reported she was married to a wealthy Cantonese man named "Art."

In China, Wong still faced criticism from the government and film community. She had trouble speaking in some areas because she spoke the Taishan dialect, not Mandarin. She said it sounded "as strange to me as Gaelic."

The stress of being a famous person affected Wong. She sometimes felt depressed or angry. In Hong Kong, she was rude to a crowd, which then became hostile. Someone shouted, "Down with Huang Liu-tsong—the stooge that disgraces China. Don't let her go ashore." Wong started crying, and a crowd rushed forward.

After a short trip to the Philippines, things calmed down. Wong joined her family in Hong Kong. She visited her father's family village near Taishan. Reports differ on whether she was welcomed warmly or with hostility. She spent over ten days there before continuing her tour.

After returning to Hollywood, Wong thought about her trip and her career. She said, "I am convinced that I could never play in the Chinese Theatre. I have no feeling for it. It's a pretty sad situation to be rejected by Chinese because I'm 'too American' and by American producers, because they prefer other races to act Chinese parts." Her father returned to Los Angeles in 1938.

To finish her contract with Paramount Pictures, Wong made several "B movies" in the late 1930s. Critics often ignored these films. However, they gave Wong non-stereotypical roles that were praised in the Chinese American press. These lower-budget films could be more daring. Wong used this to play successful, professional Chinese American characters.

These characters were proud of their Chinese heritage. They went against the usual negative portrayals of Chinese Americans in U.S. films. The Chinese consul in Los Angeles even approved the scripts for two of these films: Daughter of Shanghai (1937) and King of Chinatown (1939).

In Daughter of Shanghai, Wong played the main Asian American female lead. Her role was rewritten to make her the hero, actively driving the story. The script was so well-suited for Wong that it was sometimes called Anna May Wong Story. When the Library of Congress chose the film for preservation in 2006, they said it was "more truly Wong's personal vehicle than any of her other films."

Wong told Hollywood Magazine, "I like my part in this picture better than any I've had before... because this picture gives Chinese a break—we have sympathetic parts for a change! To me, that means a great deal." The New York Times gave the film a positive review.

In October 1937, there were rumors that Wong planned to marry her co-star, Korean-American actor Philip Ahn. Wong replied, "It would be like marrying my brother."

In King of Chinatown, Wong played a surgeon. She gave up a high-paying promotion to help the Chinese fight the Japanese invasion. The New York Times' Frank Nugent gave the film a negative review. He praised its support for the Chinese but called the film "folderol."

Paramount also used Wong to coach other actors, like Dorothy Lamour. Wong performed on radio several times. Her cabaret act, which included songs in many languages, took her across the U.S., Europe, and Australia.

In 1938, Wong auctioned off her movie costumes and gave the money to Chinese aid. The Chinese Benevolent Association of California honored her for her work. She also donated the money from a cookbook preface she wrote in 1942. Between 1939 and 1942, she made few films. Instead, she focused on events supporting the Chinese struggle against Japan.

In 1939, Wong visited Australia for over three months. She was the main star in a vaudeville show. On July 25, 1940, Wong's sister Mary died in California.

Later Years: Television and Legacy

Wong starred in Bombs over Burma (1942) and Lady from Chungking (1942). These were anti-Japanese propaganda films. She donated her salary for both films to United China Relief. The Lady from Chungking was different because it showed the Chinese as heroes, not victims. The film ended with Wong giving a speech about a "new China." The Hollywood Reporter and Variety praised Wong's acting in The Lady from Chungking.

Wong was a Democrat and supported Adlai Stevenson in the 1952 presidential election.

Later in life, Wong invested in real estate. She owned several properties in Hollywood. She turned her home in Santa Monica into four apartments called "Moongate Apartments." She managed them until 1956, when she moved in with her brother Richard.

In 1949, Wong's father died at age 91. After six years away from films, Wong returned with a small role in Impact. From August to November 1951, Wong starred in a detective series called The Gallery of Madame Liu-Tsong. She played the main character, who was a Chinese art dealer involved in detective work. The show aired during prime time. Although there were plans for a second season, the show was canceled in 1952. No copies of the show or its scripts are known to exist today. After the series, Wong's health began to decline.

In 1956, Wong hosted one of the first U.S. documentaries about China narrated by a Chinese American. It used film footage from her 1936 trip to China. Wong also made guest appearances on TV shows like Adventures in Paradise and The Barbara Stanwyck Show.

For her contributions to film, Anna May Wong received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. She was the first Asian American actress to get this honor. She is also shown as one of four supporting pillars in the "Gateway to Hollywood" sculpture.

In 1960, Wong returned to film in Portrait in Black. She still found herself playing stereotypical roles.

Later Life and Death: A Lasting Impact

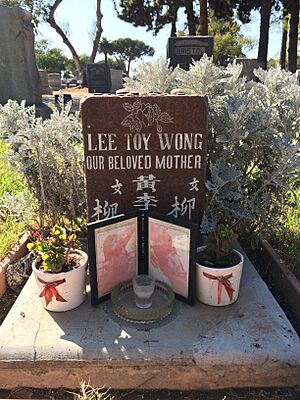

Wong was supposed to play Madame Liang in the film Flower Drum Song. However, she could not take the role due to her health. On February 3, 1961, Anna May Wong died of a heart attack at age 56. She passed away in her sleep at home in Santa Monica. This was two days after her last TV performance on The Barbara Stanwyck Show. Her ashes were buried in her mother's grave in Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles.

Legacy: Remembering Anna May Wong

Anna May Wong's image and career left a lasting impact. Through her films and public appearances, she helped people understand Chinese Americans better. This was important during a time when there was a lot of racism and discrimination. Chinese Americans were often seen as outsiders in the U.S. But Wong's films showed her as a Chinese American citizen.

For decades after her death, only Shanghai Express remained well-known in the U.S. In Europe, her films sometimes appeared at festivals. Wong was also popular in the gay community, who saw her as a symbol of being an outsider. Although Chinese critics still remembered her stereotypical roles, she was largely forgotten in China. However, her importance in Asian American film history is clear. The Anna May Wong Award of Excellence is given yearly at the Asian American Arts Awards.

Wong's image also appeared in literature. In a 1971 poem, Jessica Hagedorn described Wong's career as "tragic glamour." In 1989, John Yau wrote a poem about Wong's character in Shanghai Express. Sally Wen Mao wrote a book of poems in Wong's voice in 2019. In the 1993 film M. Butterfly, Wong's image was used as a symbol of a "tragic diva." Her life was also the subject of a play called China Doll in 1995.

In 1995, film historian Stephen Bourne organized a special showing of Wong's films.

Around the 100th anniversary of Wong's birth, people started looking at her life and career again. Three major books about her were published. Film showings were held in New York City. Anthony Chan's 2003 biography, Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong (1905–1961), was the first major book written from an Asian American viewpoint. In 2004, two more books were published: Anna May Wong: A Complete Guide to Her Film, Stage, Radio and Television Work and Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend. Anna May Wong's life and career show many complex issues that still exist today. But Anthony Chan notes that her place in Asian American film history, as its first female star, is permanent. An illustrated biography for children, Shining Star: The Anna May Wong Story, came out in 2009.

In 2016, novelist Peter Ho Davies published The Fortunes. This book explored Chinese American experiences through four characters, including a fictionalized Anna May Wong. Davies said his novel looked at the search for a true Chinese American identity.

On January 22, 2020, a Google Doodle celebrated Wong. It marked the 97th anniversary of The Toll of the Sea being released.

In 2020, actress Michelle Krusiec played Wong in the Netflix show Hollywood. This series tells an alternate history of Hollywood in the 1940s. Also in 2020, her life story was part of the PBS documentary Asian Americans.

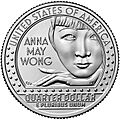

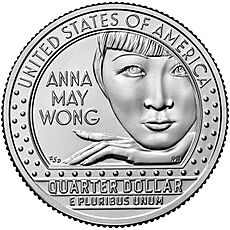

In 2021, the United States Mint announced that Wong would be one of the first women shown on the back of the quarter coin. This is part of the American Women quarters series. When the quarters with her image came out in 2022, Wong became the first Asian American to be shown on American money.

In Damien Chazelle's film Babylon (2022), Li Jun Li played Lady Fay Zhu, a character inspired by Wong.

In 2023, Mattel released a Barbie doll modeled after Wong. This was to honor Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

A movie about her life is being made by Working Title Films. British actress Gemma Chan is set to play Wong.

The first exhibition of her career using film ads will be at The San Diego Chinese Historical Museum from March 1 to 10, 2024.

Partial Filmography: Movies and TV Shows

- The Red Lantern (1919) – first role, uncredited

- Bits of Life (1921)

- The Toll of the Sea (1922) as Lotus Flower

- The Thief of Bagdad (1924) as a Mongol Slave

- Peter Pan (1924) as Tiger Lily

- A Trip to Chinatown (1926) as Ohati

- Old San Francisco (1927) as A Flower of the Orient

- Pavement Butterfly (1929) as Mah

- Piccadilly (1929) as Shosho

- Elstree Calling (1930) as Herself

- The Flame of Love (1930) as Haitang

- The Road to Dishonour (1930) as Hai-Tang

- Hai-Tang (1930) as Hai-Tang

- Daughter of the Dragon (1931) as Princess Ling Moy

- Shanghai Express (1932) as Hui Fei

- A Study in Scarlet (1933) as Mrs. Pyke

- Limehouse Blues (1934) as Tu Tuan

- Daughter of Shanghai (1937) as Lan Ying Lin

- When Were You Born (1938) as Mei Lee Ling

- Dangerous to Know (1938) as Lan Ying

- King of Chinatown (1939) as Dr. Mary Ling

- Island of Lost Men (1939) as Kim Ling

- Bombs Over Burma (1942) as Lin Ying

- Lady from Chungking (1942) as Kwan Mei

- Impact (1949) as Su Lin

- Portrait in Black (1960) as Tawny

Images for kids

-

Portrait of Anna May Wong by Carl Van Vechten, 1932, a favorite photograph of hers.

-

Carl Van Vechten photographic portrait of Wong, September 22, 1935

-

Carl Van Vechten photographic portrait of Wong, in costume for a dramatic adaptation of Gozzi's Turandot at the Westport Country Playhouse, August 11, 1937

-

Grave of her mother, Lee Toy (top), her sister, Mary (left), and Anna May Wong (right), at Angelus Rosedale Cemetery

-

In 2022, the U.S. Mint issued 468 million Wong quarters—the fifth in the American Women quarters series.

See also

In Spanish: Anna May Wong para niños

In Spanish: Anna May Wong para niños

- Anna May Wong: In Her Own Words

- Tsuru Aoki, Japanese-American silent film actress, married to Sessue Hayakawa

- Nancy Kwan, the next famed Chinese-American Hollywood actress, from the mid-20th century

- Portrayal of East Asians in Hollywood

- Racism in early American film

- Stereotypes of East and Southeast Asians in American media

- James Wong Howe

- Nellie Yu Roung Ling, first modern dancer of China and fashion designer of Chinese-American descent

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |