Georges Méliès facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

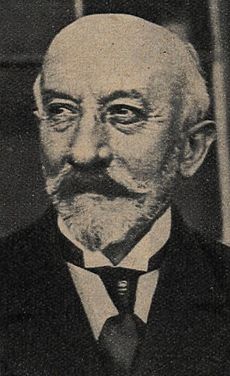

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès

|

|

|---|---|

Georges Méliès, c. 1890

|

|

| Born |

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès

8 December 1861 |

| Died | 21 January 1938 (aged 76) Paris, France

|

| Occupation | Film director, actor, set designer, illusionist, toymaker, costume designer |

| Years active | 1888–1923 |

| Spouse(s) |

Eugénie Génin

(m. 1885; died 1913)Jehanne D'Alcy

(m. 1925) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

|

|

Georges Méliès (born December 8, 1861 – died January 21, 1938) was a French moviemaker. He was a pioneer in using special effects in movies. He used techniques like multiple exposures, time-lapse photography, dissolves, and even hand-painted colors.

Some of his most famous movies include Conquest of the Pole, A Trip to the Moon, and The Impossible Voyage. These films often showed strange, dream-like journeys, similar to the adventures in Jules Verne's books. Many of his movies are considered some of the first important science fiction films. Méliès also made The Haunted Castle, which is an early horror movie.

Contents

Early Life and Movie Magic

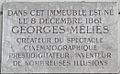

Méliès was born in Paris, France, in 1861. As a child, he loved drawing and playing with a puppet theater. When he was older, he often went to the theater. Around 1888, Méliès bought the Théatre Robert-Houdin and worked there as a magician.

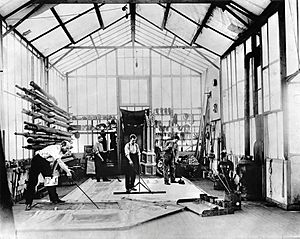

He became very interested in moviemaking after seeing a film by Antoine Lumière in 1895. In May 1896, he bought his own movie camera. He then built a movie studio to make his own films. By the end of 1896, he started a new company called Star Film.

Méliès began making movies that were usually three to nine minutes long. He often wrote, designed, filmed, and acted in almost all of his movies. He enjoyed putting magic tricks into his films. One day, while filming a street scene, his camera briefly stopped. When Méliès watched the movie later, he saw that the bus he was filming suddenly disappeared, and new vehicles appeared in its place. This discovery led him to create a famous movie trick: making things appear and disappear by stopping and starting the camera.

Famous Films and Challenges

In 1902, Méliès created his first masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon. This film was inspired by popular ideas about life on the moon at the time. Writers like H. G. Wells and Jules Verne had written about space travel. The movie was a huge success in France.

Méliès hoped to earn a lot of money by showing A Trip to the Moon in the United States. However, Thomas Edison and other moviemakers made copies of his film without permission. They earned money from Méliès's hard work, and there was nothing he could do to stop them.

Despite this, Méliès had a very successful year in 1902. He made three other major films. One was The Coronation of Edward VII, which showed the crowning of the new British King Edward VII. Méliès filmed it before the real event, as he wasn't allowed to film the actual coronation. The film was very popular, and King Edward VII reportedly enjoyed it.

Méliès also made Gulliver's Travels Among the Lilliputians and the Giants, based on the famous novel by Jonathan Swift. He also created Robinson Crusoe, based on the novel by Daniel Defoe.

In 1903, Méliès made The Kingdom of the Fairies. A film critic named Jean Mitry called it "undoubtedly Méliès's best film." It was praised for its beauty and creativity. Copies of this film are still kept in film archives today.

Méliès continued to improve his camera effects in 1903. He made films with faster transformations, like Ten Ladies in One Umbrella. He also used seven layers of images in The Melomaniac. He ended the year with The Damnation of Faust, a film based on the Faust story. This movie focused more on special effects, showing underground gardens and walls of fire and water. In 1904, he made a sequel called Faust and Marguerite.

His biggest film in 1904 was The Impossible Voyage. This film was similar to A Trip to the Moon but featured an expedition around the world, into the oceans, and even to the sun. In the movie, Méliès played Engineer Mabouloff, who leads a group on an amazing journey. Their vehicle accidentally flies to the sun, which swallows them! Eventually, they use a submarine to return to Earth. This 24-minute film was a big success.

In 1905, Méliès continued to create films. He also worked on stage shows and expanded his studio. His films from 1905 included the adventure The Palace of the Arabian Nights and Rip's Dream, based on the Rip Van Winkle story. By 1906, the "féerie" style, which Méliès was known for, started to become less popular. He began making films in other styles, like crime and family movies.

Later Career and Difficult Times

In 1907, Méliès continued to make films, including Under the Seas and a short version of Shakespeare's Hamlet. However, some film critics began to say that Méliès's work was not as good as before. They felt he was repeating old ideas or trying to copy new trends.

In 1908, Thomas Edison created the Motion Picture Patents Company to control the film industry in the United States. Méliès's Star Film Company joined this group. Star Films had to provide a lot of film each week. Méliès made 58 films that year to meet this demand. He also made one of his most ambitious films, Humanity Through the Ages, which told the history of humans. This film was not successful, but Méliès remained proud of it.

In 1909, Méliès led a meeting of European film producers in Paris. They wanted to fight against Edison's control. They decided to stop selling films and instead lease them for short periods. They also agreed to use a standard film type. Méliès was not happy with all these rules, as he preferred to sell his films directly.

Méliès continued making films in late 1909. His brother, Gaston Méliès, opened a studio in the United States. Gaston made many films, especially Westerns, to help fulfill their company's agreement with Edison. Between 1910 and 1912, Georges Méliès made very few films himself.

In 1910, Méliès temporarily stopped making films to go on a magic show tour in Europe and North Africa. Later that year, Star Films made a deal with Gaumont Film Company to distribute its films. However, Méliès also made a deal with Charles Pathé that would eventually harm his film career. Méliès accepted a large amount of money to make films, but Pathé would distribute them and could even edit them. Pathé also took ownership of Méliès's home and studio as part of the deal.

Méliès began making more elaborate films, but they failed financially. This included Baron Munchausen's Dream and The Diabolical Church Window in 1911.

In 1912, Méliès made another ambitious film, The Conquest of the Pole. This film was inspired by real expeditions to the North and South Poles. However, it also included fantasy elements like a flying vehicle with a griffith head and a giant snow monster. Like his earlier films, it featured fantastic journeys. Unfortunately, Conquest of the Pole did not make money. Because of this, Pathé decided to use its right to edit Méliès's films from then on.

One of Méliès's last big fantasy films was Cinderella or the Glass Slipper. It was a long film, but Pathé hired Méliès's rival, Ferdinand Zecca, to cut it shorter. This film also did not make a profit. After similar problems with other films, Méliès ended his contract with Pathé in late 1912.

Meanwhile, Gaston Méliès had traveled to Tahiti with his family and film crew. He filmed in the South Pacific and Asia, sending footage back to New York. However, much of the footage was damaged. Gaston lost a lot of money and had to sell the American part of Star Films. Gaston returned to Europe and died in 1915. He and Georges Méliès never spoke again.

When Méliès broke his contract with Pathé in 1913, he owed a lot of money. Even though a law during World War I stopped Pathé from taking his home and studio right away, Méliès was bankrupt. He could no longer make films. The death of his first wife, Eugénie Génin, in May 1913, also deeply affected him. The war closed his theater for a year, and Méliès left Paris with his children.

In 1917, the French army used his main studio building as a hospital for wounded soldiers. Méliès and his family used another part of the studio as a stage and performed shows there until 1923. During the war, the French army took over four hundred of Star Films' original movie prints. They melted them down to get silver and celluloid, which was used to make shoe heels. Because of this, many of Méliès's films no longer exist today.

In 1923, the Théâtre Robert-Houdin was torn down. That same year, Pathé finally took over Star Films and the Montreuil studio. In anger, Méliès burned all the negatives of his films that he had stored at the studio, along with most of his sets and costumes. Even so, over two hundred of Méliès's films have been saved and are available today.

Rediscovery and Final Years

By December 1925, Méliès was mostly forgotten and had no money. He married his long-time partner, the actress Jehanne d'Alcy. They earned a living by working at a small candy and toy stand that d'Alcy owned in the main hall of the Gare Montparnasse train station.

Around this time, people slowly started to remember Méliès's important work. In 1924, a journalist named Georges-Michel Coissac found him and interviewed him for a book about movie history. Coissac was the first film historian to show how important Méliès was to the early film industry. In 1926, a magazine found Méliès working at the train station and asked him to write about his life. By the late 1920s, more journalists began to research Méliès, creating new interest in him.

As his fame grew in the film world, he received more recognition. In December 1929, a special event was held to show his films. Méliès said it was "one of the most brilliant moments of his life."

Georges Méliès was eventually awarded the Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur, a very important French award. Louis Lumière himself presented the medal to Méliès in October 1931. Lumière called Méliès the "creator of the cinematic spectacle." However, all this praise did not help his financial situation. Méliès wrote in a letter that it was hard to work 14 hours a day without days off, in a place that was freezing in winter and boiling in summer.

In 1932, the Cinema Society helped Méliès, his granddaughter Madeleine, and Jehanne d'Alcy find a place at La Maison de Retraite du Cinéma. This was a retirement home for people in the film industry in Orly. Méliès was very relieved to be there. He wrote to an American journalist, "My best satisfaction in all is to be sure not to be one day without bread and home!"

In Orly, Méliès worked with younger directors on ideas for films that were never made. He also acted in a few advertisements in his later years.

In 1935, two directors, Henri Langlois and Georges Franju, met Méliès. In 1936, they rented an old building at the Orly retirement home to store their collection of film prints. They gave the key to Méliès, and he became the first person to look after what would later become the Cinémathèque Française, a famous film archive. Even though he couldn't make films after 1912 or stage shows after 1923, he continued to draw, write, and give advice to younger film and theater fans until he died.

By late 1937, Méliès became very ill. Langlois arranged for him to go to a hospital in Paris. Langlois and Franju visited him shortly before he died. Méliès showed them one of his last drawings, a champagne bottle with the cork popping. He told them: "Laugh, my friends. Laugh with me, laugh for me, because I dream your dreams." Georges Méliès died of cancer on January 21, 1938, at age 76. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Georges Méliès para niños

In Spanish: Georges Méliès para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |