Karl Richard Lepsius facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Karl Richard Lepsius

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 December 1810 Naumburg an der Saale, Kingdom of Saxony

|

| Died | 10 July 1884 (aged 73) Berlin, Province of Brandenburg

|

| Nationality | Prussian, German |

| Alma mater | Leipzig University, University of Göttingen, University of Berlin |

| Known for | Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien |

| Spouse(s) |

Elisabeth Klein

(m. 1846) |

| Children | 6 |

| Relatives | Bernhard Klein (father-in-law) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptology |

| Institutions | University of Berlin |

| Signature | |

|

|

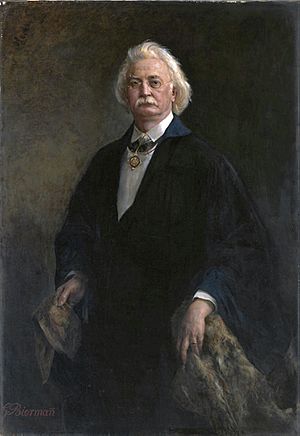

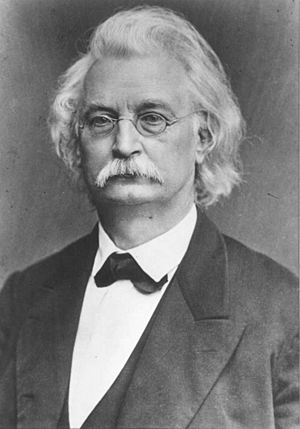

Karl Richard Lepsius (born December 23, 1810 – died July 10, 1884) was a very important German Egyptologist. This means he was a scientist who studied ancient Egypt. He was also a linguist, someone who studies languages, and a modern archaeologist, who digs up and studies old things.

He is best known for his huge work called Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien, which means "Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia."

Contents

Early Life and Studies

Karl Richard Lepsius was born in Naumburg on the Saale, in what was then Saxony. His father, Karl Peter Lepsius, was a scholar who studied ancient Greek and Roman history. His mother, Friederike, was the daughter of a composer.

Karl Richard Lepsius studied Greek and Roman archaeology at several universities. These included the University of Leipzig, the University of Göttingen, and the Frederick William University of Berlin. He earned his doctorate degree in 1833.

After finishing his studies, he traveled to Paris. There, he learned from French scholars who were studying the Egyptian language. He also visited Egyptian collections in museums across Europe. He learned about lithography and engraving, which are ways to print images.

His Important Work

After a famous French scholar named Jean-François Champollion died, Lepsius carefully studied Champollion's book on Egyptian grammar. This book had just been published. In 1836, Lepsius traveled to Italy to meet another scholar, Ippolito Rosellini. Rosellini had explored Egypt with Champollion.

Lepsius wrote letters to Rosellini, explaining more about how hieroglyphic writing worked. He pointed out that vowels (like A, E, I, O, U) were not written in ancient Egyptian.

The Prussian Expedition to Egypt

In 1842, the King of Prussia, Frederich Wilhelm IV, asked Lepsius to lead an expedition to Egypt and the Sudan. The goal was to explore and record the ancient Egyptian ruins. This trip was like earlier French expeditions, with surveyors, artists, and other experts.

The team arrived in Giza in November 1842. They spent six months studying the pyramids at Giza, Abusir, Saqqara, and Dahshur. They found 67 pyramids, which were listed in the famous Lepsius list of pyramids. They also found over 130 tombs of important people in the area.

While at the Great Pyramid of Giza, Lepsius carved a message in hieroglyphs. It honored King Friedrich Wilhelm IV and can still be seen above the pyramid's original entrance.

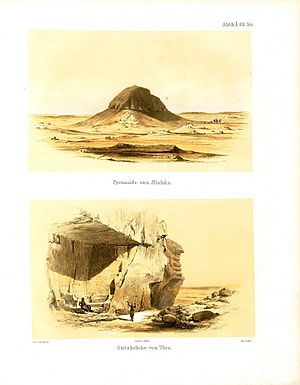

The expedition then traveled south, stopping at important sites like Beni Hasan. In 1843, they visited places in Nubia, such as Jebel Barkal and Meroë. These were old cities of the Kushitic Kingdom. Lepsius copied many inscriptions and drawings from the temples and pyramids there.

Lepsius went as far south as Khartoum. Then he traveled up the Blue Nile river. After exploring many sites in Nubia, the team returned north. They reached Thebes in November 1844. They spent four months studying the temples and tombs on the west bank of the Nile, like the Ramesseum and the Valley of the Kings. They spent another three months on the east bank, at the temples of Karnak and Luxor. They tried to record as much as they could.

After Thebes, they stopped at Coptos, the Sinai, and sites in the Egyptian Delta, like Tanis. They returned to Europe in 1846.

Publishing the Discoveries

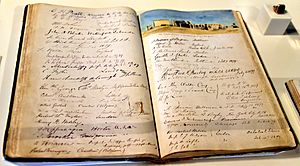

The most important result of this expedition was the book Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien. This huge work had twelve volumes with almost 900 plates. These plates showed ancient Egyptian inscriptions, monuments, and landscapes. It also included notes and descriptions.

These drawings and maps of temple and tomb walls were the main source of information for scholars for a long time. They are still useful today because they sometimes show monuments that have since been destroyed or covered by sand. For example, Lepsius described a "Headless Pyramid" that was later lost. It was rediscovered in 2008.

Later Career and Legacy

When Lepsius returned to Europe in 1845, he married Elisabeth Klein. In 1846, he became a professor of Egyptology at Berlin University. He also became the co-director of the Ägyptisches Museum (Egyptian Museum) in 1855. Later, in 1865, he became the director of the museum.

In 1866, Lepsius went back to Egypt. There, he found the Decree of Canopus at Tanis. This was an important inscription, similar to the Rosetta Stone. It was written in both Egyptian (hieroglyphic and demotic) and Greek.

Lepsius was the head of the German Archaeological Institute in Rome from 1867 to 1880. From 1873 until his death in 1884, he was also the head of the Royal Library at Berlin. He was the editor of a very important scientific journal for Egyptology, which is still published today.

Lepsius published many works about Egyptology. He is seen as the founder of this modern scientific field. He even created the term Totenbuch, which means "Book of the Dead". He also studied African languages. He created a Standard Alphabet for writing down languages that didn't have a written form. This alphabet was published in 1855 and updated in 1863.

Family Life

On July 5, 1846, Karl Richard Lepsius married Elisabeth Klein. They had six children. Some of their children became famous in their own fields. For example, G. Richard Lepsius became a geologist, Bernhard Lepsius became a chemist, and Reinhold Lepsius became a portrait painter. Their youngest son, Johannes Lepsius, became a theologian and humanist.

Major Works

- 1842. Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter (The Egyptian Book of the Dead).

- 1849. Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien (Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia). This was his huge 12-volume work.

- 1852. Briefe aus Aegypten, Aethiopien und der Halbinsel des Sinai (Letters from Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Sinai Peninsula). This book was translated into English in 1853.

- 1855. Das allgemeine linguistische Alphabet (The General Linguistic Alphabet). This book explained his system for writing down languages.

- 1856. Über die XXII. ägyptische Königsdynastie (About the 22nd Egyptian Royal Dynasty).

- 1863. Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages. This was the updated version of his alphabet for languages.

- 1880. Nubische Grammatik (Nubian Grammar). This book included a grammar of the Nubian languages.

Death

Karl Richard Lepsius suffered from stomach ulcers, which later became cancerous. He passed away on July 10, 1884, at the age of 73.

See also

In Spanish: Karl Richard Lepsius para niños

In Spanish: Karl Richard Lepsius para niños

- Lepsius list of pyramids

- Standard Alphabet by Lepsius

- Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |