French campaign in Egypt and Syria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids French campaign in Egypt and Syria |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Second Coalition | |||||||

Click an image to load the appropriate article. Left to right, top to bottom: Battles of the Pyramids, the Nile, Cairo, Abukir (1799), Abukir (1801), Alexandria (1801) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 40,000 soldiers 10,000 sailors |

||||||

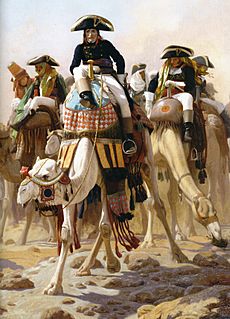

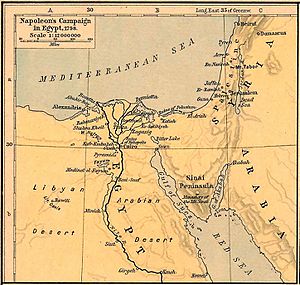

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was a military operation led by Napoleon Bonaparte. He took his French army to the Ottoman lands of Egypt and Syria. Napoleon said his goal was to protect French trade and to start scientific studies in the area.

This campaign was part of a larger naval effort in the Mediterranean Sea in 1798. It included capturing Malta and the Greek island of Crete. The French fleet then arrived in the Port of Alexandria. However, the campaign ended with Napoleon's defeat. French troops had to leave the region.

Even though the military part failed, the expedition was a big success for science. It led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone. This discovery helped create the study of Egyptology, which is the study of ancient Egypt. Napoleon and his army, called the Armée d'Orient, won some early battles. They even had a good start in Syria. But they were eventually defeated. A major reason was the loss of their supporting fleet. The British Royal Navy destroyed it at the Battle of the Nile.

Contents

Planning the Trip to Egypt

Why Invade Egypt?

When the invasion happened, France was ruled by a group called the Directory. They often used the army to keep order. Napoleon, a very successful general, was their main military leader. He had already won many battles in Italy.

The idea of making Egypt a French colony had been discussed for a while. Napoleon and a French diplomat named Talleyrand talked about it. In early 1798, Napoleon suggested the expedition to Egypt. He convinced the Directory to create a group of scientists and artists for the trip. Napoleon also wanted to weaken Great Britain's trade in the Middle East. He hoped to team up with France's ally, Tipu Sultan in India. Tipu Sultan was against British control there. Since France couldn't attack Great Britain directly, they decided to strike indirectly. They wanted to create a "double port" connecting the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. This was like an early idea for the Suez Canal.

At that time, Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire. But it was not directly controlled by the Ottomans. Instead, it was in chaos, with fighting among the ruling Mamluk leaders. In France, there was a lot of interest in Egyptian culture. Many thinkers believed Egypt was where Western civilization began. French traders in Egypt complained about being bothered by the Mamluks. Napoleon wanted to follow in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. He told the Directory that once he conquered Egypt, he would connect with Indian princes. Together, they would attack the British in India. The Directory agreed to the plan in March, even though it was expensive. They also saw it as a way to send the popular Napoleon away from the center of power.

Getting Ready to Sail

Rumors spread as 40,000 soldiers and 10,000 sailors gathered in French ports. A large fleet was put together at Toulon. It included 13 large warships, 14 smaller warships, and 400 transport ships. To avoid being stopped by the British fleet, led by Admiral Nelson, the expedition's destination was kept secret. Only Napoleon and a few trusted people knew. Napoleon was the commander.

The fleet from Toulon was joined by other ships from Genoa, Civitavecchia, and Bastia. Admiral Brueys was in charge of the entire fleet. Just as the fleet was about to leave, a problem came up with Austria. The Directory called Napoleon back in case war started. But the problem was solved quickly. Napoleon was then ordered to go to Toulon as fast as possible.

Taking Over Malta

When Napoleon's fleet reached Malta, he asked the Knights of Malta for permission. He wanted his ships to enter the port for water and supplies. The Grand Master, von Hompesch, said only two foreign ships could enter at a time. This rule would make resupplying the large French fleet take weeks. It would also leave them open to attack by the British fleet. So, Napoleon ordered an invasion of Malta.

The French Revolution had greatly reduced the Knights' money and their ability to fight. Many of the Knights were French and refused to fight against Napoleon. French troops landed in Malta on the morning of June 11. They met some resistance but pushed forward. The Knights' small force of about 2,000 men was not ready. After a fierce battle, most of the Knights in the west surrendered. Napoleon then started talks. Facing a much stronger French force and having lost western Malta, von Hompesch surrendered the main fortress of Valletta.

From Alexandria to Syria

Landing in Egypt

Napoleon left Malta for Egypt. For thirteen days, his fleet avoided being seen by the Royal Navy. On July 1, they arrived near Alexandria and landed there. This was not exactly where Napoleon had planned to land.

On the day of the landing, Napoleon told his soldiers, "I promise to each soldier who returns from this expedition, enough to purchase six arpents of land." This meant they would get a lot of land.

General Menou was the first Frenchman to land in Egypt. Napoleon and Kléber landed together and met Menou at night. They were at the cove of Marabout, where the first French flag was raised in Egypt.

On the night of July 1, Napoleon heard that Alexandria would fight back. He quickly brought troops ashore without waiting for cannons or cavalry. He marched on Alexandria with 4,000 to 5,000 men. At 2 AM on July 2, he marched in three groups. Menou attacked a fort on the left and was wounded. Kléber was in the center and was also wounded. Louis André Bon attacked the city gates on the right. Alexandria was defended by Koraim Pasha and 500 men. After some fighting, the defenders gave up and ran away. French soldiers broke into the city, even though Napoleon had ordered them not to.

Once all the troops were off the ships, Admiral Brueys was told to take the fleet to Aboukir Bay. He was to anchor the warships there or take them to Corfu. These steps were important because the British fleet was expected soon. It had been seen near Alexandria a day before the French arrived. It was safer to avoid a naval battle. A defeat at sea would be terrible. It was better for the army to march quickly by land to Cairo. This would surprise the enemy leaders before they could set up defenses.

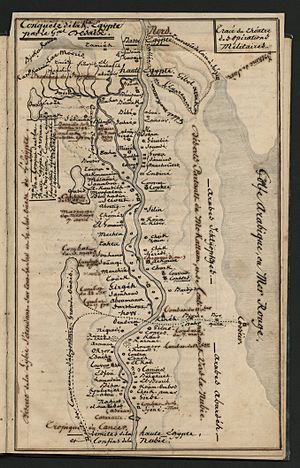

Land Victory, Sea Defeat

Louis Desaix marched his troops across the desert. He reached Demenhour, about 24 kilometers from Alexandria, on July 6. Meanwhile, Napoleon left Alexandria, leaving Kléber in charge. General Dugua marched to Rosetta. His orders were to capture the entrance to the port. The French fleet was to follow the river to Cairo and meet the army at Rahmanié. On July 8, Napoleon arrived at Demenhour. On July 10, they marched to Rahmanié to wait for the fleet with supplies. The fleet arrived on July 12. The army started marching again that night, with the fleet following.

Strong winds suddenly pushed the fleet towards the enemy. The enemy fleet was supported by 4,000 Mamluks, peasants, and Arabs. The French fleet had more ships but still lost its gunboats. Napoleon heard the gunfire and ordered his land forces to attack. They charged the village of Chebreiss. After two hours of fierce fighting, they captured it. The enemy fled towards Cairo, leaving 600 dead.

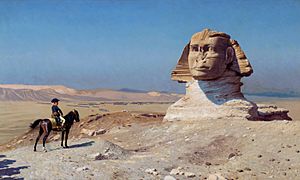

After a day of rest, the French army continued to chase the enemy. On July 20, they arrived near the village of Embabé. The heat was terrible, and the army was tired. But there was no time to rest. Napoleon lined up his 25,000 troops for battle. They were about 15 kilometers from the Pyramids of Giza. He is said to have pointed to the pyramids behind the enemy and shouted, "Soldiers, see the tops of the Pyramids!" This was the start of the Battle of the Pyramids. The French won against about 21,000 Mamluks. (About 40,000 Mamluk soldiers did not join the battle.) The French used a giant infantry square formation. Their cannons and supplies were safe inside. Around 300 French soldiers and 6,000 Mamluks were killed.

Dupuy's troops chased the defeated enemy. That night, they entered Cairo. The Mamluk leaders, Mourad and Ibrahim, had left the city. On July 22, Cairo's leaders met Napoleon and offered to give him the city. Three days later, he moved his main base there. Desaix was ordered to follow Mourad, who had gone to Upper Egypt. A group of soldiers watched Ibrahim, who was heading towards Syria. Napoleon himself led the chase for Ibrahim. He defeated him at Salahie and pushed him completely out of Egypt.

The transport ships had sailed back to France. But the warships stayed and helped the army along the coast. The British fleet, led by Horatio Nelson, had been looking for the French fleet for weeks. They didn't find it in time to stop the landings in Egypt. But on August 1, Nelson found the French warships. They were anchored in a strong defensive spot in the Bay of Abukir. The French thought they could only be attacked from one side, with the other side protected by the shore. During the Battle of the Nile, the British fleet managed to send half of their ships between the land and the French line. This allowed them to attack from both sides. In a few hours, 11 out of 13 French warships and 2 out of 4 French smaller warships were captured or destroyed. The remaining four ships fled. This ruined Napoleon's goal of making France stronger in the Mediterranean Sea. Instead, the British took full control.

After the Battle of the Pyramids, Napoleon set up a French government in Cairo. He harshly stopped later uprisings. Napoleon tried to get the support of local Egyptian scholars, called ulema. But scholars like Al-Jabarti strongly criticized the French ideas and culture.

Napoleon's Rule in Egypt

After the naval defeat at Aboukir, Napoleon's campaign stayed on land. His army still managed to gain control in Egypt. However, they faced many local uprisings. Napoleon started acting like the absolute ruler of Egypt. He held a big celebration for the Nile River. He gave gifts to the people and special robes to his officers.

Napoleon tried to get the Egyptian people to support him. He issued statements saying he was freeing them from Ottoman and Mamluk control. He praised Islam and claimed friendship between France and the Ottoman Empire. This helped him gain some support at first. It also led to admiration from Muhammad Ali of Egypt, an Albanian leader. Muhammad Ali later succeeded in reforming Egypt and declaring its independence from the Ottomans. Napoleon's secretary, Bourienne, wrote that Napoleon was not truly interested in Islam. He only cared about its political use.

Soon after Napoleon returned, Mohammed's birthday was celebrated with great ceremony. Napoleon himself led military parades. He wore oriental clothes and a turban for the festival. During this time, a local council gave him the title Ali-Bonaparte. This happened after Napoleon called himself "a worthy son of the Prophet" and "favorite of Allah." He also took strong steps to protect pilgrim groups traveling from Egypt to Mecca.

Despite these efforts, the Egyptians were not convinced. Napoleon had placed heavy taxes on them to support his army. They continued to attack him. They used any means, including surprise attacks, to force the French out of Egypt. Military punishments did not stop these attacks.

On September 22, the anniversary of the First French Republic was celebrated. Napoleon organized a huge party. A large circus was built in Cairo's biggest square. It had 105 columns, each with a flag for a French region. In the center was a huge monument. Seven altars had the names of heroes killed in the French Revolutionary Wars. Two victory arches were built. One wooden arch was in Azbakiyya Square. The second arch had the words "There is no god but God, and Muhammad is his prophet." It was decorated with scenes from the Battle of the Pyramids. This painting showed the French winning, which upset the Egyptians they were trying to befriend.

After a speech, people shouted "Vive la République!" (Long live the Republic!). Cannons were fired. Later, Napoleon held a feast for 200 people in a Cairo garden. He sent soldiers to put a French flag on top of a pyramid.

Napoleon's rule in Egypt was important for Coptic history. On July 30, 1798, he appointed Jirjis Al-Jawhary, a leading Coptic person, as General Steward of Egypt. Napoleon declared that Copts were now equal citizens. They could carry weapons, ride horses, and wear any clothes they liked. He also punished those who had harmed Copts. In return, he asked Copts to be loyal to the French Republic. In December 1798, he appointed four Coptic members to his new advisory assembly.

Chasing the Mamluks

After losing at the Pyramids, Mourad Bey went to Upper Egypt. On August 25, 1798, General Desaix sailed up the Nile with his troops. By August 31, Desaix reached Beni Suef and faced supply problems. He continued up the Nile to Behneseh and then towards Minya. The Mamluks did not fight. The French boats returned on September 12. Desaix learned that the Mamluks were in the Faiyum plain by September 24.

The first small fight happened on October 3. Another small fight followed, which used up French food and ammunition.

On October 7, Mourad Bey's troops attacked the French. The French formed three squares, one large and two smaller ones at its corners. The Mamluks attacked fiercely but were pushed back. The Mamluks tried to use their four cannons. But a strong attack led by Captain Jean Rapp captured them.

After hours of fighting, the French attacked. The Mamluks fled south.

Cairo Uprising

In 1798, Napoleon led the French army into Egypt. They quickly took Alexandria and Cairo. But in October, people in Cairo became unhappy with the French. They started an uprising. People spread weapons and built strong defenses, especially at the Al-Azhar Mosque. A French commander, Dominique Dupuy, was killed by the rebels. Napoleon's assistant, Joseph Sulkowski, was also killed. Local citizens, encouraged by religious leaders, swore to kill every Frenchman they found. Frenchmen found in homes or on streets were killed without mercy. Crowds gathered at the city gates to keep Napoleon out. He was forced to take a different route to enter through the Boulaq gate.

The French army was in a difficult spot. The British were threatening French control of Egypt after their victory at the Battle of the Nile. Murad Bey and his army were still fighting in Upper Egypt. Generals Menou and Dugua could barely control Lower Egypt. Peasants across the region joined the uprising against the French.

The French responded by placing cannons in the Citadel. They fired at areas where rebels were. During the night, French soldiers moved around Cairo. They destroyed any roadblocks and defenses they found. The rebels were soon pushed back by the strong French forces. They slowly lost control of their parts of the city. Napoleon personally hunted down rebels in the streets. He forced them to hide in the Al-Azhar Mosque. Napoleon then ordered his cannons to fire on the Mosque. The French broke down the gates and stormed the building. They killed many people inside. By the end of the uprising, 5,000 to 6,000 people in Cairo were dead or wounded.

Syria Campaign

Exploring the Ancient Canal

With Egypt calm and under his control, Napoleon used this time to visit Suez. He wanted to see if an ancient canal, said to have been built by pharaohs, could connect the Red Sea and the Nile. Before leaving, he gave Cairo back some self-rule. A new council of 60 members replaced the military government.

Then, Napoleon traveled to the Red Sea. He was with scientists and a 300-man escort. After three days of marching across the desert, they reached Suez. After giving orders to improve the defenses at Suez, Napoleon crossed the Red Sea. On December 28, he went into Sinai to look for the famous mountains of Moses. On his way back, he was almost caught by the rising tide. Back at Suez, the expedition found the remains of the ancient canal built by Senusret III and Necho II.

Ottoman Attacks

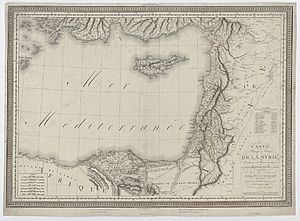

Meanwhile, the Ottomans in Constantinople (now Istanbul) heard about the French fleet's destruction at Aboukir. They thought this meant Napoleon and his army were trapped in Egypt and finished. Sultan Selim III decided to declare war on France. He sent two armies to Egypt. The first army, led by Jezzar Pasha, had 12,000 soldiers. It was joined by more troops from Damascus, Aleppo, Iraq, and Jerusalem. The second army, led by Mustafa Pasha, started from Rhodes with about 8,000 soldiers. He also expected 42,000 more soldiers from Albania, Constantinople, Asia Minor, and Greece. The Ottomans planned two attacks on Cairo: one from Syria by land, and one from Rhodes by sea, landing near Aboukir or Damietta.

Siege of Jaffa

After marching 60 miles across the desert, the French army arrived in Gaza. They rested for two days, then moved to Jaffa. This city had tall walls and towers. Jezzar had put his best troops there, with 1,200 Ottoman gunners. Jaffa was a key entry point to Syria. Its port could be used by the French fleet. So, Napoleon had to capture it before moving on. He began the siege from March 3 to March 7.

The French quickly took the outer defenses. Napoleon sent a messenger to the city's commander, asking him to surrender. But the commander killed the messenger and ordered an attack. This attack was pushed back. That evening, French cannonballs caused one of the towers to fall. Despite fierce resistance, Jaffa fell. For two days and nights, there was intense fighting. About 4,500 prisoners were killed. Some historians say Napoleon could not afford to keep so many prisoners or let them rejoin Jezzar's army.

Before leaving Jaffa, Napoleon set up a local council for the city. He also created a large hospital at the Carmelite monastery on Mount Carmel. This was to treat soldiers who had caught the plague. Symptoms of the plague had appeared since the siege began. Napoleon was worried about the plague spreading. To calm his army, he reportedly visited the sick, spoke with them, and touched them. He said, "See, it's nothing." Then he told others, "It was my duty, I'm commander-in-chief." Some later historians say Napoleon avoided touching plague sufferers. They believe his visits were made up later for propaganda. For example, the painting Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) shows Napoleon touching a sick man. This painting was made the same year Napoleon became emperor.

Battle of Mount Tabor

From Jaffa, the army headed for Acre. On the way, they captured Haifa and its supplies. They also took castles at Jaffe and Nazareth, and even the town of Tyre. The siege of Acre began on March 18. But the French could not take it. This is where the Syrian campaign stopped. The city was defended by new Ottoman elite soldiers. They were led by Jezzar Pasha. Acre was right on the coast, so it could get supplies and reinforcements from British and Ottoman ships.

After sixty days of attacks and two bloody, undecided assaults, the city was still not captured. Acre was waiting for more troops by sea. A large Ottoman army was also gathering in Asia to march against the French. To find out what this army was doing, Jezzar ordered a big attack on Napoleon's camp. This attack was supported by cannons and naval gunfire from the British. Napoleon pushed Jezzar's troops back to their walls. Then he went to help Kléber. Kléber was holding a position with 4,000 Frenchmen against 20,000 Ottomans at Mount Tabor. Napoleon came up with a clever plan. He sent Murat and his cavalry across the River Jordan to protect the river crossing. He sent Vial and Rampon to march on Nablus. Napoleon himself placed his troops between the Ottomans and their supplies. These moves worked in what became known as the Battle of Mount Tabor. The enemy army was surprised and defeated. They had to retreat, leaving behind their camels, tents, supplies, and 5,000 dead soldiers.

Acre Siege Ends

Returning to besiege Acre, Napoleon learned that Rear-Admiral Perrée had landed seven large cannons at Jaffa. Napoleon then ordered two more attacks, but both were strongly pushed back. A fleet flying the Ottoman flag was seen. Napoleon realized he had to capture the city before those ships arrived with more troops. A fifth major attack was ordered. This attack took the outer defenses. The French flag was planted on the wall. The Ottomans were pushed back into the city. Their firing slowed down. It seemed Acre was about to fall.

One of the fighters on the Ottoman side was Phélippeaux. He was a French engineer and had been Napoleon's classmate. Phélippeaux ordered cannons to be placed in the best spots. New trenches were dug quickly behind the ruins the French had captured. At the same time, Sidney Smith, the British fleet commander, and his sailors landed. These things gave the defenders new courage. They pushed Napoleon's forces back. Both sides fought with great determination. Three final attacks by the French were all pushed back. This convinced Napoleon that it was not wise to keep trying to capture Acre.

Leaving Acre

The French army was in a difficult situation. The enemy could attack them from behind as they retreated. The soldiers were tired and hungry in the desert. They also had many soldiers suffering from the plague. Carrying these sick soldiers in the middle of the army would spread the disease. So, they had to be carried at the back, where they were most at risk from the Ottomans. The Ottomans wanted revenge for the killings at Jaffa. There were two hospitals, one on Mount Carmel and one at Jaffa. Napoleon ordered all sick soldiers at Mount Carmel to be moved to Jaffa and Tantura. The horses used for cannons were left behind at Acre. Napoleon and his officers gave their horses to the transport officer. Napoleon walked to set an example for his troops.

To hide their retreat from the siege, the army left at night. When they reached Jaffa, Napoleon ordered three groups of plague sufferers to be moved. One group went by sea to Damietta. Another went by land to Gaza. A third went by land to Arish. During the retreat, the army destroyed everything in their path. Livestock, crops, and houses were all ruined. Gaza was the only place spared, because it remained loyal to Napoleon.

Back in Egypt

Finally, after four months away from Egypt, the expedition returned to Cairo. They had 1,800 wounded soldiers. They had lost 600 men to the plague and 1,200 to enemy fighting. Meanwhile, Ottoman and British messengers had brought news to Egypt about Napoleon's failure at Acre. They said his army was mostly destroyed and Napoleon himself was dead. When Napoleon returned, he stopped these rumors. He re-entered Egypt as if leading a victorious army. His soldiers carried palm branches, which are symbols of victory.

Battles in Upper Egypt

The French wanted to get rid of the Mamluks or force them out of Egypt. By this time, the Mamluks had been pushed from Faiyum into Upper Egypt. General Desaix told Napoleon about his situation. Soon, he received 1,000 cavalry and three light cannons. These were led by General Davout.

On December 29, 1798, the French army reached Girga, the capital of Upper Egypt. They waited there for boats to bring them ammunition. But twenty days passed, and no boats arrived. Meanwhile, Mourad Bey had contacted leaders from Jeddah and Yanbu. He asked them to cross the Red Sea to fight the French. He also sent messengers to Nubia for more troops. Hassan Bey Jeddaoui also joined the fight against the French.

Hearing about these efforts, General Davout moved his forces on January 2–3, 1799. He met many armed men near the village of Sawaqui. The rebels were easily defeated, and 800 of them died. However, local people kept gathering around Asyut to fight the French. On January 8, Davout met another local force at Tahta. He killed 1,000 men and made the rest run away.

Meanwhile, Mourad Bey's army got stronger. A thousand sheriffs arrived from across the Red Sea. Two hundred and fifty Mamluks, led by Hassan Bey Jeddaoui and Osman Bey Hassan, also joined. Nubians and North Africans, led by Sheikh Al-Kilani, joined too. They camped near the village of Houé. All were supported by the people of Upper Egypt.

Battle of Samhud

The combined Muslim army marched into the desert on January 21, 1799. They reached Samhud near Qena. On January 22, Desaix formed three squares: two of infantry and one of cavalry. The cavalry was in the middle for protection. As soon as the French were ready, the enemy cavalry surrounded them. A group of Arabs from Yanbu fired at their left side. Desaix told his riflemen to attack them. Rapp and Savary, leading cavalry, charged the enemy from the side.

The Arabs were attacked so strongly that they fled. About thirty of them were killed or wounded. Later, the Arabs from Yanbu regrouped and attacked again. They tried to capture the village of Samhud. But the French riflemen attacked them fiercely and fired continuously. The Arabs had to retreat after losing many people.

However, the large Muslim forces kept advancing, shouting loudly. The Mamluks charged the squares led by Generals Friant and Belliard. But they were strongly pushed back by cannon and rifle fire. They had to retreat, leaving their dead on the battlefield.

Mourad Bey and Osman Bey Hassan, who led the Mamluk troops, could not stand against Davout's cavalry charge. They left their positions and caused the whole army to flee. The French chased their enemies until the next day. They stopped only after pushing them beyond the Cataracts of the Nile.

Battle of Aswan

Desaix continued marching south, reaching Esneh on February 9. Meanwhile, Osman Bey Hassan had placed his forces at the foot of a mountain near Aswan. On February 12, General Davout found the enemy positions. He quickly set up his troops. He formed his cavalry in two lines and charged the Mamluks. Osman Bey Hassan was badly wounded, and his horse was killed. The French cavalry charged with great force, and the fight became very intense. However, the Mamluks were defeated and had to leave the battlefield.

Battle of Abnud

On March 8, 1799, General Belliard led his forces to fight 3,000 Meccan infantry and 350 Mamluks. This battle took place on the plain of Abnud, south of Qena. The French, using their square formation, advanced on the Muslim forces. The Muslims then defended themselves inside the houses of Abnud. The fighting lasted for hours. Afterward, the French reached the village courtyard and set the houses on fire. The Muslims were forced to escape, and any remaining injured were killed.

Battle of Beni Adi

The Mamluks continued to encourage local people to fight the French. On May 1, 1799, General Davout's forces killed at least 2,000 local farmers near Asyut. As they chased Murad Bey into Upper Egypt, the French discovered ancient monuments. These included sites at Dendera, Thebes, Edfu, and Philae.

Taking Kosseir

On May 29, 1799, General Belliard captured Kosseir on the Red Sea. He had marched through the desert to stop more Meccan troops from arriving. He also wanted to prevent any possible invasion from the English.

From Abukir to French Withdrawal

Land Battle at Abukir

In Cairo, the army found the rest and supplies they needed. But they could not stay long. Napoleon learned that Murad Bey had escaped the pursuit by French generals. Murad Bey was now moving towards Lower Egypt. Napoleon marched to attack him at Giza. He also learned that 100 Ottoman ships were off Aboukir, threatening Alexandria.

Without delay, Napoleon ordered his generals to quickly meet the army led by Saïd-Mustapha, the pasha of Rumelia. This army had joined forces with Murad Bey and Ibrahim.

First, Napoleon went to Alexandria. From there, he marched to Aboukir. The fort at Aboukir was now strongly defended by the Ottomans. Napoleon arranged his army so that Mustapha's forces would have to win or be destroyed. Mustapha's army had 18,000 soldiers and several cannons. Trenches protected them on the land side. They could also communicate freely with the Ottoman fleet at sea. Napoleon ordered an attack on July 25. The Battle of Abukir began. In a few hours, the trenches were taken. 10,000 Ottomans drowned in the sea, and the rest were captured or killed. Much of the credit for the French victory went to Murat, who captured Mustapha himself. Mustapha's son was in charge of the fort. He and all his officers survived but were captured. They were sent back to Cairo as part of a French victory parade. When the people of Cairo saw Napoleon return with these high-ranking prisoners, they welcomed him as a prophet-warrior. They believed he had predicted his own triumph.

Napoleon Leaves Egypt

The land battle at Abukir was Napoleon's last action in Egypt. It helped restore his reputation after the French naval defeat at the same place a year earlier. The Egyptian campaign was not going anywhere. Also, political problems were growing back home in France. A new part of Napoleon's career was starting. He felt he had done all he could in Egypt. He also felt that his remaining forces were not enough for any important expeditions outside Egypt. He saw that the army was getting weaker from battles and disease. Soon, they might have to surrender and be captured. This would ruin all the fame he had gained. So, Napoleon decided to return to France. He had learned about events in France from the British fleet, especially through a newspaper sent by Sidney Smith. Napoleon believed France was in trouble. Its enemies had taken back French conquests. France was unhappy with its government and wanted the peace it had signed earlier. Napoleon felt France needed him and would welcome him back.

He only told a few trusted friends about his secret return. He left Cairo in August, pretending to take a trip in the Nile Delta. He was with scientists and generals. On August 23, a message told the army that Napoleon had given his command to General Kléber. The soldiers were angry that Napoleon and the French government had left them behind. But this anger soon passed. The troops trusted Kléber. He convinced them that Napoleon had not left for good. He said Napoleon would soon return with more troops from France. As night fell, the frigate Muiron quietly docked by the shore, with three other ships. Some worried when a British ship was seen as they left. But Napoleon said, "Bah! We'll get there, luck has never abandoned us, we shall get there, despite the English."

Napoleon's Journey to France

On their 41-day trip back, they did not meet any enemy ships. Some sources suggest Napoleon had made a secret deal with the British fleet. Others think this is unlikely. It has been suggested that Sidney Smith and other British commanders helped Napoleon avoid the British navy. They might have thought he would help the royal family back in France. But there is no strong proof for this idea.

On October 1, Napoleon's small group of ships entered the port at Ajaccio. Strong winds kept them there until October 8, when they left for France. This was the last time Napoleon was in his homeland. When the coast came into view, ten British ships were seen. Admiral Ganteaume suggested changing course towards Corsica. But Napoleon said, "No, this move would lead us to England, and I want to get to France." This brave decision saved them. On October 8, the ships anchored off Fréjus. Since no one was sick and the plague in Egypt had ended six months before they left, Napoleon and his group were allowed to land right away without waiting in quarantine. At 6 PM, he left for Paris. He stopped at Saint-Raphaël, where he built a pyramid to remember the expedition.

Siege of Damietta

On November 1, 1799, the British fleet, led by Admiral Sidney Smith, landed an army of Janissaries near Damietta. This was between Lake Manzala and the sea. The French soldiers in Damietta, 800 infantry and 150 cavalry, were led by General Jean-Antoine Verdier. They met the Turks. According to Kléber's report, 2,000 to 3,000 Janissaries were killed or drowned. 800 surrendered, including their leader Ismaël Bey. The Turks also lost 32 flags and 5 cannons.

End of the Campaign

The troops Napoleon left behind were supposed to be safely sent home. This was part of the Convention of El Arish. Kléber had agreed to this with Smith and the Ottoman commander Kör Yusuf in early 1800. But Britain refused to sign. Kör Yusuf then sent an army of 30,000 Mamluks to attack Kléber.

Kléber defeated the Mamluks at the Battle of Heliopolis in March 1800. Then he stopped an uprising in Cairo. On June 14, a Syrian student named Suleiman al-Halabi killed Kléber with a dagger. Command of the French army went to General Menou. He was in charge from July 3 until August 1801.

The British and Ottomans then started their land attack. The French were defeated by the British in the Battle of Alexandria on March 21. They surrendered at Fort Julien in April. Then Cairo fell in June. Finally, Menou was surrounded in Alexandria from August 17 to September 2. He eventually surrendered to the British. Under the terms of his surrender, the British General John Hely-Hutchinson allowed the French army to go home on British ships. Menou also gave all Egyptian ancient artifacts, like the Rosetta Stone, to Britain. After initial talks in Al Arish on January 30, 1802, the Treaty of Paris on June 25 ended all fighting between France and the Ottoman Empire. Egypt was returned to the Ottomans.

Scientific Discoveries

An interesting part of the Egyptian expedition was the large group of scientists and scholars who went with the French army. There were 167 of them. Some people see this as a sign of Napoleon's interest in new ideas and knowledge. Others see it as a clever way to hide the real reasons for the invasion: to increase Napoleon's power.

These scholars included engineers, artists, and experts in many fields. Among them were the geologist Dolomieu, the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the chemist Claude Louis Berthollet, and the artist Vivant Denon. Also present were the mathematician Jean-Joseph Fourier and the naturalist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire.

Their first goal was to help the army. They planned to open a Suez Canal, map roads, and build mills for food. They founded the Institut d'Égypte (Egyptian Institute). Their aim was to spread new ideas and improve farming and building techniques in Egypt. They created a science magazine called Décade égyptienne. During the expedition, the scholars also studied and drew the plants and animals of Egypt. They became interested in the country's resources. The Egyptian Institute built laboratories, libraries, and a printing press. The group did a lot of work. Some of their discoveries were not fully organized until the 1820s.

A young engineering officer, Pierre-François Bouchard, found the Rosetta Stone in July 1799. Many ancient items found by the French in Egypt, including the stone, were given to the British when the campaign ended. This was part of Menou's agreement with Hutchinson. The French scholars' research in Egypt led to a 4-volume book called Mémoires sur l'Égypte (published from 1798 to 1801). A bigger book, Description de l'Égypte, was published later from 1809 to 1821, on Napoleon's orders. These books about Napoleon's discoveries in Egypt sparked a great interest in Ancient Egyptian culture. This led to the beginning of Egyptology in Europe.

The scientists also tried out hot air ballooning in Egypt. Several months after the revolt of Cairo in 1798, an inventor named Nicolas-Jacques Conté and mathematician Gaspard Monge built a hot air balloon. It was made of paper and colored red, white, and blue like the French flag. They launched the balloon over Azbakiyya Square in front of many people. But the balloon soon fell, causing panic. The French had also planned to show hot air balloon flight during their celebrations in 1798. But the scientists had lost their equipment after the Battle of the Nile.

The Printing Press in Egypt

The printing press was first brought to Egypt by Napoleon. He brought French, Arabic, and Greek printing presses with his expedition. These presses were much faster, more efficient, and better quality than any used in Istanbul at the time. In the Middle East, Africa, India, and even much of Eastern Europe and Russia, printing was a small, specialized activity until at least the 18th century. From about 1720, the Mutaferrika Press in Istanbul printed many things. Egyptian religious leaders knew about some of these.

Napoleon's first Arabic statements had many mistakes. Much of the Arabic was poorly translated and grammatically incorrect. Often, the statements were so badly written that they were hard to understand. A French expert on the Middle East, Jean Michel de Venture de Paradis, likely with help from Maltese assistants, translated Napoleon's first French statements into Arabic. The Maltese language is related to Egyptian Arabic. But classical Arabic is very different in grammar and words. Venture de Paradis, who had lived in Tunis, understood Arabic grammar and words. But he did not know how to use them naturally.

The Sunni Muslim religious leaders of the Al-Azhar University in Cairo reacted with disbelief to Napoleon's statements. Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, a Cairo cleric and historian, found the statements amusing, confusing, and outrageous. He criticized the French for their poor Arabic grammar and awkward writing style. During Napoleon's invasion, al-Jabarti wrote a lot about the French and their ways of taking control. He rejected Napoleon's claim that the French were "muslims" (the Arabic word was used incorrectly). He also poorly understood the French ideas of a republic and democracy. These words did not exist in Arabic at that time.

European Control and Influence

The Napoleonic invasion of Egypt is often seen by experts today as "the first act of modern European imperialism." Imperialism is when a powerful country tries to control other countries. The invasion is also criticized for helping create the idea of a "civilizing mission." This was a belief in the 19th century that European colonial empires had a duty to "civilize" other parts of the world.

Timeline of Key Events

- 1798

- May 19 – French fleet leaves Toulon

- June 11 – Malta is captured

- July 1 – French troops land at Alexandria

- July 13 – Battle of Shubra Khit, French victory

- July 21 – Battle of the Pyramids, French land victory

- August 1-2 – Battle of the Nile, British navy defeats French ships at Aboukir Bay

- August 10 – Battle at Salheyeh, French victory

- October 7 – Battle of Sédiman, French victory

- October 21 – Cairo Uprising begins

- 1799

- February 11-19 – Siege of El Arish, French victory

- March 7 – Siege of Jaffa, French victory

- April 8 – Battle at Nazareth, French victory (Junot with 500 men defeats 3000 Ottoman soldiers)

- April 11 – Battle of Cana, French victory

- April 16 – Napoleon helps Kléber's troops at Mount Tabor

- May 20 – Siege of Acre, French troops retreat after eight attacks

- August 1 – Battle of Abukir, French victory

- August 23 – Napoleon leaves Egypt, giving command to Kléber

- 1800

- January 24 – Kléber signs the Convention of El Arish with British Admiral Sidney Smith

- February – French troops start to leave, but British Admiral Keith refuses the agreement

- March 20 – Battle of Heliopolis, Kléber wins against 30,000 Ottomans

- June 14 – A Kurd named Suleiman al-Halabi kills Kléber in Cairo. General Menou takes command

- September 3 – The British take back Malta from the French

- 1801

- March 8 – British troops land near Aboukir

- March 21 – Battle of Alexandria, French defeat. Menou's army stays in Alexandria for the siege

- March 31 – Ottoman army arrives at El-Arich

- April 19 – British and Ottoman forces capture Fort Julien at Rosetta after four days of bombing, opening the Nile River

- June 27 – General Belliard surrenders in Cairo

- August 31 – Siege of Alexandria ends with Menou's surrender

See also

- Mediterranean campaign of 1798

- Anglo-Turkish War (1807–1809)

- Crusader invasions of Egypt – 1154–116*

Sources

- Napoleon Was Here! An interactive journey following Napoleon's expedition to Egypt, The National Library of Israel

- Burleigh, Nina. Mirage. Harper, New York, 2007. ISBN: 978-0-06-059767-2

- Jourquin, Jacques, Journal du capitaine François dit 'le dromadaire d'Égypte', 2 vol., introduction critique et annexes par Jacques Jourquin, éditions Tallandier (couronné par l'Académie française), 1984, new edition, 2003.

- Mackesy, Piers. British Victory in Egypt, 1801: The End of Napoleon's Conquest. Routledge, 2013. ISBN: 978-1134953578

- Miot, Jacques. Narrative of the French expedition in Egypt, and the operations in Syria. Translated from the French. (1816)

- Miot, Jacques-François. Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire des expéditions en Égypte et en Syrie. Deuxième édition. (1814).

- Rickard, J French Invasion of Egypt, 1798–1801, (2006)

- Strathern, Paul. Napoleon in Egypt: The Greatest Glory. Jonathan Cape, Random House, London, 2007. ISBN: 978-0-224-07681-4 online

- Melanie Ulz: Auf dem Schlachtfeld des Empire. Männlichkeitskonzepte in der Bildproduktion zu Napoleons Ägyptenfeldzug (Marburg: Jonas Verlag 2008), ISBN: 978-3-89445-396-1.

- Napoleonic Egypt Digital Collection; Rare Books and Special Collections Library; the American University in Cairo

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |