Sidney Smith (Royal Navy officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sir Sidney Smith

|

|

|---|---|

Commodore Smith wounded at Alexandria 1801.

|

|

| Born | 21 June 1764 Westminster, London, England |

| Died | 26 May 1840 (aged 75) Paris, France |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1777–1815 |

| Rank | Admiral |

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards | Order of the Sword Order of the Tower and Sword Knight Commander of the Bath |

Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith (born June 21, 1764 – died May 26, 1840) was a brave British naval officer. He was also involved in intelligence work. He served in important wars like the American Revolutionary War, the French Revolutionary War, and the Napoleonic Wars. He eventually became an Admiral.

Smith was known for being very direct and for taking action on his own. This sometimes caused problems with his leaders and other officers. But his skills, intelligence, and willingness to take risks led him to be involved in many different tasks. These included fighting wars, working as a diplomat, and even spy work. He became a hero in Britain after successfully defending Acre in 1799. This stopped Napoleon's plans to conquer more lands in the Sinai.

Later in his life, Napoleon said about Smith: "That man made me miss my destiny." This shows how important Smith's actions were.

Contents

Sidney Smith, as he liked to be called, came from a family with a history in the military and navy. He was born in Westminster, London. His father, Captain John Smith, was in the Guards. Sidney went to Tonbridge School until 1772. He joined the Royal Navy in 1777 and fought in the American Revolutionary War. He served on ships like Tortoise and HMS Unicorn. On the Unicorn, he fought against the American ship Raleigh in 1778.

Smith showed great bravery under Admiral Rodney in the battle near Cape St Vincent in January 1780. Because of this, he was made a lieutenant on the 74-gun ship Alcide on September 25. This was special because he was younger than the required age of 19.

He also did well under Admiral Thomas Graves at the Battle of the Chesapeake in 1781. And he served under Admiral George Rodney again at the Battle of the Saintes. After these successes, he got his first command, the small warship Fury . He was soon promoted to captain a larger frigate. However, after the peace treaty in 1783, he was put on half pay and had no active command.

During this time of peace, Smith decided to travel to France. He started getting involved in intelligence by watching the building of a new naval port at Cherbourg. He also traveled in Spain and Morocco, which were also potential enemies of Britain.

In 1790, Smith asked for permission to serve in the Royal Swedish Navy. Sweden was at war with Russia at the time. King Gustav III of Sweden made him a commander of a light squadron. He also became one of the King's main naval advisors. Smith led his forces in an attempt to clear the Bay of Viborg of the Russian fleet. Later, he fought in the Battle of Svensksund.

In this battle, the Russians lost 64 ships and over a thousand men. The Swedes lost only four ships and had few casualties. For his bravery and success, King Gustav III made Smith a knight. He was given the title of Commander Grand Cross of the Swedish Svärdsorden (Order of the Sword). Smith was allowed by King George III to use this title in Britain.

French Revolutionary Wars Service

In 1792, Smith's younger brother, John, was sent to the British embassy in Constantinople (now Istanbul). Smith got permission to travel to Turkey. While he was there, war broke out with Revolutionary France in January 1793. Smith gathered some British sailors and joined the British fleet. This fleet, led by Admiral Lord Hood, had taken control of the French port of Toulon. They were invited by French Royalist forces who supported the old king.

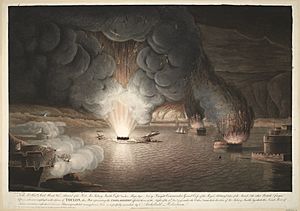

When Smith arrived in December 1793, French Revolutionary forces had surrounded the port. Among them was an artillery colonel named Napoleon Bonaparte. The British and their allies did not have enough soldiers to defend the port well, so they decided to leave. Smith, who was serving as a volunteer, was given the job of burning as many French ships and supplies as possible. This was to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. Even though he tried his best, more than half of the French ships were captured undamaged. This was because the Spanish forces sent to help him did not provide enough support. Some important naval figures like Nelson and Collingwood blamed Smith for not destroying the entire French fleet.

When he returned to London, Smith was given command of the ship HMS Diamond. In 1795, he joined the Western Squadron under Sir John Borlase Warren. This squadron had many skilled and daring captains, including Sir Edward Pellew. Smith fit right in. One time, he even took his ship almost into the port of Brest to watch the French fleet.

In July 1795, Captain Smith, commanding HMS Diamond, took control of the Îles Saint-Marcouf. These islands are off the coast of Normandy. He used two of his gun vessels, HMS Badger and HMS Sandfly, to get materials and men to fortify the islands. He set up a temporary naval base there. More defenses were built by engineers, and detachments of Royal Marines and Royal Artillery were stationed. The islands became an important base for blocking the port of Le Havre. They were also used to stop coastal shipping and as a safe place for French people escaping the revolution. The Navy held these islands for almost seven years.

Smith was very good at operations close to shore. On April 19, 1796, he and his secretary John Wesley Wright were captured. They were trying to take a French ship from Le Havre harbor. Smith had taken the ship's boats into the harbor. But the wind stopped as they tried to leave, and the French were able to recapture the ship with Smith and Wright on board. Instead of being exchanged for other prisoners, which was the usual custom, Smith and Wright were taken to the Temple prison in Paris. Smith was to be charged with arson for burning the fleet at Toulon. Since Smith was on half pay at the time, the French did not consider him an official combatant. While in prison, he had a drawing made of himself and his secretary by the French artist Philippe Auguste Hennequin. This drawing is now in the British Museum. Another drawing by Hennequin, showing only Smith, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Smith was held in Paris for two years. There were many attempts to exchange him, and he had frequent contact with French Royalists and British agents. Captain Jacques Bergeret, who was captured in April 1796 with the frigate Virginie, was sent from England to Paris to arrange his own exchange. When the French government refused, he returned to London. The French authorities often threatened to try Smith for arson, but they never did. Finally, in 1798, Royalists helped Smith and Wright escape. They pretended to be taking him to another prison. The Royalists brought the two Englishmen to Le Havre. From there, they boarded a fishing boat and were picked up on May 5 by HMS Argo in the English Channel. They arrived in London on May 8, 1798. Bergeret was then released, as the British government considered the prisoner exchange complete.

Service in the Mediterranean Sea

After Nelson's big victory at the Battle of the Nile, Smith was sent to the Mediterranean. He was made captain of HMS Tigre. This was a captured French ship that had been brought into the Royal Navy. It was not just a naval job. He was also ordered to report to Lord St Vincent, the commander of the Mediterranean fleet. St Vincent made him a Commodore. This meant he could take British ships under his command in the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean region). He also had a military and diplomatic mission to Istanbul. His brother was already there as a diplomat to the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government). Their job was to make the Turks stronger against Napoleon. They also had to help the Turks destroy the French army stuck in Egypt. This dual role made Nelson, who was the senior officer under St Vincent, feel that Smith was taking over his authority in the Levant. Nelson's dislike of Smith further hurt Smith's reputation in the navy.

Napoleon had defeated the Ottoman forces in Egypt. He then marched north along the Mediterranean coast with 13,000 troops. He went through the Sinai and into what was then the Ottoman province of Syria. Here, he took control of much of the southern part of the province, which is now Israel and Palestine. He also took one town in today's Lebanon, Tyre. On his way north, he captured Gaza and Jaffa. He was very harsh to the people there. He also massacred 3,000 captured Turkish soldiers. Napoleon's army then marched to Acre.

Smith sailed to Acre and helped the Turkish commander Jezzar Pasha. He helped strengthen the defenses and old walls. He also gave them more cannons, which were operated by sailors and Marines from his ships. Smith also used his control of the sea to capture the French siege artillery. This artillery was being sent by ship from Egypt. He also stopped the French army from using the coastal road from Jaffa by firing at their troops from the sea.

The siege began in late March 1799. Smith anchored HMS Tigre and Theseus. Their powerful broadsides (firing all cannons from one side) helped defend the city. The French attacked many times but were always pushed back. Several attempts to dig tunnels under the walls were also stopped. By early May, new French siege artillery had arrived by land. A hole was made in the defenses. However, the attack was again stopped, and Turkish reinforcements from Rhodes were able to land. On May 9, after another heavy bombardment, the final French attack happened. This too was pushed back. Napoleon then began planning to take his army back to Egypt. Soon after this, Napoleon left his army in Egypt and sailed back to France. He managed to avoid the British ships patrolling the Mediterranean.

Smith tried to arrange for the remaining French forces to surrender and return home. These forces were under General Kléber. Smith signed the Convention of El-Arish. However, Nelson believed that the French forces in Egypt should be completely destroyed, not allowed to return to France. Because of Nelson's influence, the treaty was canceled by Lord Keith. Keith had taken over from St Vincent as commander-in-chief.

The British decided instead to land an army under Sir Ralph Abercromby at Abukir Bay. Smith and his ship Tigre helped train and transport the landing forces. He also worked with the Turks. But because he was not popular, he lost his diplomatic role and his naval position as Commodore in the eastern Mediterranean. The invasion was successful, and the French were defeated. Abercromby was wounded and died soon after the battle. After this, Smith supported the army under Abercromby's replacement, John Hely-Hutchinson. This army besieged and captured Cairo. Finally, they took the last French stronghold of Alexandria. The French troops were eventually sent back home. The terms were similar to those Smith had arranged earlier in the Convention of El-Arish.

Service in British Waters

When Smith returned to England in 1801, he received some honors and a pension of £1,000 for his service. But he was again overshadowed by Nelson. Nelson was being celebrated as the winner of the Battle of Copenhagen. During the short Peace of Amiens, Smith was elected a Member of Parliament for Rochester in Kent in the election held in 1802.

When war with France started again in 1803, Smith was assigned to the southern North Sea. He worked off the coast between Ostend and Flushing. He was part of the forces trying to stop Napoleon's planned invasion of Britain.

Smith was interested in new ways of fighting. In 1804 and 1805, he worked with the American inventor Robert Fulton. Fulton was developing torpedoes and mines to destroy the French invasion fleet. This fleet was gathering off the French and Belgian coasts. However, an attempt to use these new weapons, along with Congreve rockets, in an attack on Boulogne failed. Bad weather and French gunboats stopped the attackers. Despite this setback, it was suggested that the rockets, mines, and torpedoes be used against the combined French and Spanish Fleet in Cádiz. This was not needed, as the combined fleet sailed to defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar in October 1805.

More Mediterranean Service

In November 1805, Smith was promoted to rear admiral. He was again sent to the Mediterranean under the command of Collingwood. Collingwood had become the commander-in-chief after Nelson's death. Collingwood sent Smith to help King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies take back his capital of Naples. Napoleon's brother, King Joseph, had been given the Kingdom of Naples.

Smith planned a campaign using local Calabrian troops. He also had 5,000 British officers and men to march north on Naples. On July 4, 1806, they defeated a larger French force at the Battle of Maida. Once again, Smith's way of dealing with his superiors caused him to be replaced as commander of the land forces, even though he had been successful. He was replaced by Sir John Moore, one of Britain's most skilled soldiers. Moore changed Smith's plan. He decided to make the island of Sicily a strong British base in the Mediterranean.

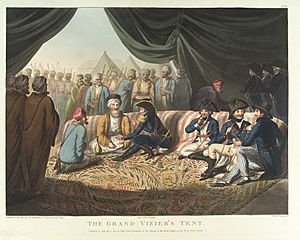

Smith was sent to join Admiral Sir John Thomas Duckworth's expedition to Constantinople in February 1807. This mission aimed to stop the French from making an alliance with the Turks. Such an alliance would allow the French army to pass freely to Egypt. On February 19, Duckworth sent Smith's division to deal with a Turkish squadron that was blocking the fleet's path. Smith skillfully destroyed it. Despite Smith's great experience in Turkish waters, his knowledge of the Turkish court, and his popularity with the Turks, he was kept in a less important role during the campaign. Even when Duckworth finally asked for his advice, it was not followed. Instead of letting Smith negotiate with the Turks, Duckworth retreated back through the Dardanelles under heavy Turkish fire. Although this was a defeat, the withdrawal under fire was presented as a heroic act. In the summer of 1807, Duckworth and Smith were called back to England.

Portugal and Brazil Missions

In October 1807, Spain and France signed a treaty to divide Portugal between them. In November 1807, Smith was given command of an expedition to Lisbon. His mission was either to help the Portuguese fight off the attack or to destroy the Portuguese fleet and block the harbor at Lisbon if resistance failed. Smith arranged for the Portuguese fleet to sail for Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which was a Portuguese colony at the time. He was involved in planning an attack on the Spanish colonies in South America with the Portuguese. This was against his orders. However, he was called back to Britain in 1809 before any of these plans could be carried out. He received much public praise for his actions and was seen as a hero. But the government continued to be suspicious of him, and he was not given any official honors. Smith was promoted to vice admiral on July 31, 1810. In the Royal Navy at that time, promotion from Post Captain to Admiral happened automatically based on how long someone had served, not as a special reward. Later that year, in October 1810, he married Caroline Rumbold. She was the widow of a diplomat, Sir George Rumbold, with whom Smith had worked.

After safely escorting the Portuguese Royal Family to Brazil, Admiral Smith was honored by Prince-Regent John. He received the Grand Cross of the newly restored Order of the Tower and Sword.

Back to the Mediterranean

In July 1812, Smith sailed again for the Mediterranean. His new flagship was the 74-gun Tremendous. He was appointed as second in command to Vice Admiral Sir Edward Pellew. His job was to blockade Toulon. He moved his flag to the larger Hibernia, a 110-gun ship. The French ships did not leave port to fight the British. In early 1814, the Allied armies entered Paris, and Napoleon gave up his power. With peace coming and Napoleon defeated, Smith began his journey back to England.

Peace and Waterloo

In March 1815, Napoleon escaped from Elba. He gathered his experienced troops and marched on Paris. There, he was made Emperor of the French again. Smith was traveling back to England but had only reached Brussels by June. Smith, his wife, and stepdaughter attended the Duchess of Richmond's ball on the night of June 15/16. Three days later, hearing the sounds of a great battle, he rode out of Brussels. He went to meet the Duke of Wellington. Smith found him late in the day, just after Wellington had won the Battle of Waterloo. Smith started making arrangements to collect and treat the many wounded soldiers from both sides. He was then asked to accept the surrender of the French garrisons at Arras and Amiens. He also had to make sure that the Allied armies could enter Paris without a fight. This would make it safe for King Louis XVIII to return to his capital. For these and other services, he finally received a British knighthood, the KCB. So, he was no longer just "the Swedish Knight."

Smith then became involved in the anti-slavery cause. The Barbary pirates had operated for centuries from ports in North Africa. They had enslaved captured sailors and even raided European coasts, including England and Ireland, to kidnap people. Smith attended the Congress of Vienna to ask for money and military action to end the practice of taking slaves.

Smith had built up significant debts because of his diplomatic expenses. The British government was very slow to pay him back. He also lived a fancy lifestyle, and his efforts to stop the slave trade cost a lot of money. In Britain at that time, people who owed money were often put in prison until their debts were paid. So, Smith moved his family to France, settling in Paris. Eventually, the government did pay back his expenses and increased his pension. This allowed him to live comfortably. Despite trying many times to get another command at sea, he never did. He died on May 26, 1840, from a stroke. He is buried with his wife in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

On April 7, 1801, Sidney, New York (Delaware County) was named in Sir Sidney Smith's honor. In June 1811, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. In 1838, he was promoted to GCB in the Coronation Honours. Sidney Smith Barracks, in Mandate Palestine, were named after him. Now it is the site of Bustan Ha-Galil in northern Israel. On July 14, 1941, the French forces in Syria and Lebanon signed their surrender to the British.

See also

In Spanish: William Sidney Smith para niños

In Spanish: William Sidney Smith para niños

- Barrow, John (1848): The life and correspondence of Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith, Volume 1

- Barrow, John (1848): The life and correspondence of Admiral Sir William Sidney Smith, Volume 2 (from 1800 onwards.)