Waterloo campaign: Waterloo to Paris (2–7 July) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Waterloo campaign: Waterloo to Paris (2–7 July) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Waterloo campaign | |||||||

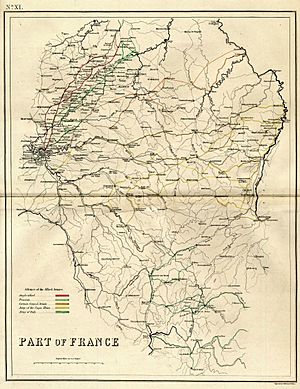

Part of France engraved by J. Kirkwood, showing the invasion routes of the Seventh Coalition armies in 1815. Red: Anglo-allied Army; light green: Prussian Army; orange: North German Federal Army; yellow: Army of the Upper Rhine; dark green: Army of Italy. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Seventh Coalition: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Louis-Nicolas Davout Rémy Joseph Isidore Exelmans Dominique Vandamme |

Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| French Army order of battle | Prussian Army order of battle | ||||||

After their big defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815, the French Army of the North, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, quickly retreated towards France. The two main commanders of the Seventh Coalition armies, the Duke of Wellington (leading the Anglo-allied army) and Prince Blücher (leading the Prussian army), agreed to chase the French closely. They wanted to make sure the French couldn't reorganize.

For the next week, from June 18 to June 24, the French army kept retreating. Even though some fresh French troops joined them, the Coalition generals didn't give them a chance to regroup. By June 24, the French troops who fought at Waterloo were at Laon. The French troops who fought at the Battle of Wavre were at Rethel. Meanwhile, the Prussians were near Aisonville-et-Bernoville, and the Anglo-allies were near Cambrai.

During the following week, from June 25 to July 1, the French army reached Paris. The Coalition forces were only about a day's march behind them. By July 1, the Anglo-allied army faced the French in the northern parts of Paris. The French had strong defenses there. The Prussians had crossed the River Seine and were getting ready to attack Paris from the southwest.

The third week of the campaign began with the Prussians getting stronger on the south side of Paris. After two smaller battles at Sèvres (July 2) and Issy (July 3), the French government and their army commander, Marshal Davout, realized they couldn't win. They knew that fighting more would only cause more deaths and possibly destroy Paris. So, they stopped fighting and asked for a ceasefire.

Representatives from both sides met at the Palace of St. Cloud. They agreed that Paris would surrender under the terms of the Convention of St. Cloud. On July 4, the French Army left Paris and moved south. On July 7, the two Coalition armies marched into Paris. The French government bodies stopped meeting. The French King Louis XVIII returned to Paris the next day and became king again. Over the next few months, the new French government took control of all areas, including some forts that were still loyal to Napoleon. A new peace treaty was signed in November of that year.

Contents

July 2: The Prussians Advance on Paris

Prussian Army Moves to South Paris

At dawn on July 2, Prince Blücher moved his entire Prussian army towards the south side of Paris. He planned to take control of the high ground near Meudon and Châtillon. These hills offered a good position for an attack.

The 9th Brigade, which was the lead group of the III Corps, quickly went to Versailles to take it over. The main part of the III Corps waited for two hours at Rocquencourt for the I Corps to arrive. As the I Corps moved forward, it sent a small group to its left. This group was told to go towards Saint-Cloud and watch for any French movements.

When the I Corps reached Ville-d'Avray, they learned that the French were rebuilding a bridge at Saint-Cloud. They also found out that the French had many soldiers in the Bois de Boulogne forest. So, the 3rd Brigade was ordered to go towards Saint-Cloud to stop any French attacks from that side.

Battle for Sèvres and Nearby Hills

At 3:00 PM, the Prussian 1st Brigade reached Sèvres. The French had strong positions there, holding the town and the hills of Bellevue. Their light troops were hidden in gardens and vineyards. The 1st Prussian Brigade, supported by the 2nd and 4th brigades, attacked. Even though the French fought bravely, the Prussians forced them to leave Sèvres and fall back to Moulineaux.

The French tried to hold their ground at Moulineaux, but the Prussians, led by Steinmetz, chased them closely and defeated them again. While the 1st Prussian Brigade was winning, the 2nd Brigade and the reserve artillery moved towards the Meudon hills. The 4th Brigade then took control of Sèvres.

Later that evening, the French, after getting their troops back together at Issy, tried to take back Moulineaux. But their attack failed, and they were pushed back to Issy.

Issy Captured and French Retreat

At Issy, the French army was much stronger. They had fifteen battalions of soldiers, many cannons, and cavalry. Their light infantry was in the vineyards in front of the village.

Around 10:30 PM, the Prussians heard the French troops marching away. It seemed like the French were leaving in a messy way. The Prussians quickly took advantage of this. Parts of the 1st and 2nd Prussian brigades attacked the French. The French fled back towards the Vaugirard area of Paris in such confusion that the Prussians could have entered Paris right then if more of their troops had been ready.

During the night, the Prussian I Corps set up its positions. Its right side was on the Clamart hill, its center on the Meudon hill, and its left side in Moulineaux. Sèvres was still held by the Prussians, and their lead troops were in Issy. The French lost about 3,000 soldiers that day defending Moulineaux and Issy.

Paris Surrounded by Coalition Forces

While the Prussian I Corps was successfully moving against the south side of Paris, the III Corps moved towards Le Plessis-Piquet. Its lead troops reached the Châtillon hills late in the evening. The IV Corps, which was the reserve army, stayed in Versailles for the night.

All day, the Anglo-allied army stayed in front of the fortified lines on the north side of Paris. Wellington built a bridge at Argenteuil and sent troops across the Seine River. These troops secured villages like Asnières, Courbevoie, and Suresnes on the left bank of the Seine. This opened a more direct way for them to communicate with the Prussians.

The Coalition commanders had successfully trapped the French forces inside Paris. Wellington was ready to attack the north side of Paris if needed. Blücher had a strong position on the mostly open and undefended south side. He was ready to storm the city with his army. This plan made it hard for the French commander, Davout, to decide where to focus his defense. If he attacked one army with most of his forces, the other army would attack him. If both armies attacked at the same time, his forces would be too spread out.

Wellington Offers Peace Terms

In a letter to Blücher, Wellington explained the terms he would offer the French. He said that attacking Paris before the Austrian army arrived would be very costly. If they waited for the Austrians, the city could be taken easily. However, the kings and leaders traveling with the Austrian army would likely want to spare Paris, just like they did in 1814, because King Louis XVIII was their friend. In that case, they would agree to terms similar to what Wellington was offering. So, Wellington suggested it was better to end the war immediately rather than wait a few more days.

The French government knew they were in a bad situation. They also knew that the Bavarian, Russian, and Austrian armies were coming. They saw that fighting more was pointless. So, they told their representatives to meet with Wellington. They informed him that Napoleon had left Paris on June 29 to go to the United States. They asked for fighting to stop.

Wellington replied that since Napoleon, the main problem, was gone, only the terms of surrender remained. He thought the Anglo-allied and Prussian armies should stay where they were. The French army should leave Paris and cross the Loire River. Paris would be protected by its own National Guards until the King returned. He offered to try to convince Blücher to stop fighting if they agreed to these terms. But he clearly stated that he would not stop fighting as long as any French soldiers remained in Paris. After hearing this, the French representatives left.

Army Positions on July 2 Evening

Here's where the armies were positioned on the night of July 2:

- Prussian Army:

* The I Corps had its right side on Clamart hill, its center on Meudon hill, and its left side at Moulineaux. Its lead troops were at Issy. * The III Corps' 9th Brigade was at Châtillon. The 10th and 11th brigades were in front of Velisy. The 12th Brigade was at Châtenay and Sceaux. * The IV Corps' 16th Brigade was at Montreuil. The 13th Brigade was near Viroflay. The 14th Brigade was near Rocquencourt.

- Anglo-allied Army:

* The Anglo-allied troops stayed in front of the defenses of Saint-Denis. Small groups were at Asnières, Courbevoie, and Suresnes, on the south side of the Seine River.

- French Army:

* The French army's right side held the defenses on the right bank of the Seine, watching the Anglo-allied army. Some troops were in the Bois de Boulogne forest. * The left side, including the Imperial Guard, stretched from the Seine to the Orleans road. They had many soldiers in Vaugirard.

July 3: The Battle of Issy and Surrender

Battle of Issy

At 3:00 AM on July 3, French General Vandamme attacked Issy from Vaugirard. Issy was defended by Prussian soldiers behind quickly built barricades, supported by cannons. After four hours of fighting, the French attacks failed to push out the Prussians. With more Prussian soldiers arriving, the French pulled back.

During the fighting at Issy, other Prussian groups were also fighting French forces between St. Cloud and Neuilly. The French were driven back to the bridge at Neuilly. So, the Prussian I Corps, which started the campaign with battles along the Sambre River, also had the honor of ending it with battles at Issy and Neuilly on the Seine River.

Meanwhile, the Anglo-allied army, led by Wellington, had moved to Gonasse. They built a bridge over the Seine at Argenteuil, crossed it, and connected with Blücher's army. A British army group was also moving towards Neuilly on the left side of the Seine.

When it became clear that the French attack had failed and that the two Coalition armies were now connected, the French commanders decided to surrender. They just wanted to make sure the surrender terms were not too harsh.

So, at 7:00 AM, the French suddenly stopped firing. A French general was sent to the Prussian I Corps, which was the closest Coalition force to Paris. He offered to surrender and asked for an immediate ceasefire.

Formal Surrender of Paris

When Blücher heard about the French ceasefire, he asked for a French negotiator with more authority before he would agree to stop fighting. He suggested the Palace of St. Cloud as the meeting place and moved his headquarters there.

Wellington had already arrived to meet Blücher at St. Cloud. Officers with full power from their commanders met there. Their discussions led to the surrender of Paris under the terms of the Convention of St. Cloud.

July 4–7: Coalition Armies Enter Paris

Coalition Armies Enter Paris

On July 4, as agreed in the Convention of St. Cloud, the French army, led by Marshal Davout, left Paris and marched towards the Loire River. The Anglo-allied troops then took control of Saint-Denis, Saint Ouen, Clichy, and Neuilly. On July 5, the Anglo-allied army took control of Montmartre.

On July 6, the Anglo-allied troops occupied the gates of Paris on the right side of the Seine River. The Prussians occupied the gates on the left bank.

On July 7, the two Coalition armies marched into Paris. The French government bodies were informed of what happened and stopped meeting. The Chamber of Deputies protested, but it was useless. Their President resigned, and the next day, the doors were closed, and Coalition troops guarded the entrances.

Aftermath: What Happened Next

Napoleon Surrenders and Goes to Saint Helena

On July 8, the French King, Louis XVIII, entered Paris. People cheered as he returned to his palace. It was during this entry that a local official, Gaspard, comte de Chabrol, gave a speech to Louis XVIII. He started by saying, "Sire, one hundred days have passed away since your majesty... left your capital..." This speech gave the name "Hundred Days" to the important events of that year.

Also on July 8, Napoleon Bonaparte boarded a French ship called the Saale at Rochefort. He planned to sail to America.

On July 10, the wind was good, but a British fleet appeared. Napoleon saw that it would be hard to escape their ships. So, after talking with Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland, he decided to surrender to him on board HMS Bellerophon. He reached this ship on July 15. The next day, Captain Maitland sailed for England, arriving on July 24. Even though Napoleon protested, he was not allowed to land in England. The British Government decided to send him to the island of Saint Helena. He was moved to HMS Northumberland and sailed to his prison on the remote South Atlantic island. Napoleon remained a prisoner on Saint Helena until he died in 1821.

Forts Surrender

The forts that were left behind the British and Prussian armies, near their main paths, were taken over by a Coalition force. This force was led by Prince Augustus of Prussia, with the Prussian II Corps and British cannons. Here's how the sieges went:

| Fortress | Start Date | Surrender Date |

|---|---|---|

| Maubeuge |

|

|

| Landrecies |

|

|

| Marienberg |

|

|

| Philippeville |

|

|

| Rocroy |

|

|

Prince Augustus was ready to start the siege of Charlemont. But on September 20, he received news from Paris that all fighting in France was to stop.

Peace Treaty

The Treaty of Paris was signed on November 20, 1815. This treaty had much tougher rules for France than the treaty from the year before. France had to pay 700 million francs as a penalty. The country's borders were also made smaller, back to what they were on January 1, 1790. France also had to pay more money to help build new defenses in neighboring countries.

Under the treaty, parts of France would be occupied by up to 150,000 soldiers for five years, and France had to pay for them. However, the Coalition occupation, led by the Duke of Wellington, was only needed for three years. The foreign troops left in 1818.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |