Waterloo campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Waterloo campaign |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the Seventh Coalition | |||||||

Click an image to load the battle. Left to right, top to bottom: Battles of Quatre Bras, Ligny, Waterloo |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 124,000–126,000 c. 350 guns |

Wellington: 107,000 Blücher: 123,000 Total: 230 000 |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 63,000 | 61,000 | ||||||

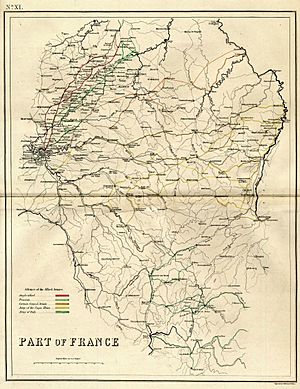

The Waterloo campaign was a short but very important series of battles in 1815. It lasted from June 15 to July 8. The main fight was between the French Army, led by Napoleon Bonaparte, and two armies from the War of the Seventh Coalition. These were the Anglo-allied army, led by the Duke of Wellington, and the Prussian army, led by Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher.

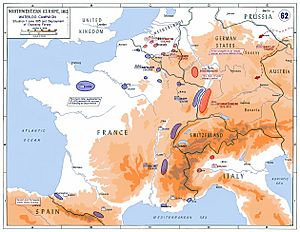

This war began because other European powers refused to accept Napoleon as Emperor of France. He had returned from exile on the island of Elba. Instead of waiting for them to attack France, Napoleon decided to strike first. He hoped to defeat his enemies one by one before they could join forces. He chose to attack the British and Prussian armies in what is now Belgium. This area was then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The fighting started on June 15. The French pushed back Prussian outposts and crossed the Sambre river. This placed Napoleon's forces between Wellington's army to the west and Blücher's army to the east. The most famous battle, the Battle of Waterloo, happened on June 18. It was a major turning point.

Contents

- Why the Waterloo Campaign Happened

- Armies Get Ready for Battle

- Fighting Begins: June 15

- Key Battles: June 16

- The Day Between: June 17

- The Decisive Battle: Waterloo (June 18)

- The Battle of Wavre (June 18–19)

- Chasing Napoleon: Invasion of France

- The Final Days: Paris Falls

- What Happened Next

- Timeline of Key Events

- See also

Why the Waterloo Campaign Happened

After being sent away to the island of Elba, Napoleon escaped and returned to France on March 1, 1815. The king, Louis XVIII, quickly left Paris. Napoleon entered Paris the very next day.

However, the major powers of Europe, like Austria, Great Britain, Prussia, and Russia, were meeting at the Congress of Vienna. They did not welcome Napoleon back. Instead, they declared him an "outlaw" on March 13, 1815. This started the War of the Seventh Coalition. Napoleon had hoped for peace, but war was now certain.

On March 25, these European powers signed a new agreement. Each country promised to send 150,000 soldiers to fight Napoleon. Great Britain had a smaller army, so they paid other countries to help.

The plan was to invade France on July 1, 1815. This date was chosen so all the armies could be ready at the same time. This would allow them to use their combined strength against Napoleon. However, this delay also gave Napoleon more time to build up his own forces.

Napoleon decided to attack first, rather than wait. He wanted to strike his enemies before they were fully prepared and working together. He believed that if he could defeat some of the main Coalition armies, he could force them to make peace.

He chose to attack in Belgium for several reasons:

- The British and Prussian armies were spread out. He thought he could defeat them separately.

- The Russian and Austrian armies were still far away.

- Many British soldiers were new recruits, as older soldiers were fighting in America.

- The Dutch troops helping the British were not well-trained.

- A French victory might encourage people in French-speaking Belgium to support him.

Armies Get Ready for Battle

When Napoleon returned, he found France's army was small. But by the end of May, he had gathered about 198,000 soldiers. He placed some of his forces in different areas to watch for enemy attacks.

His main army, called L'Armée du Nord (the "Army of the North"), was led by Napoleon himself. This army would fight in the Waterloo campaign.

The Coalition forces also got ready. By early June 1815, Wellington's Anglo-allied army had about 93,000 soldiers. Their headquarters were in Brussels. Blücher's Prussian army had about 116,000 men, with headquarters in Namur. These armies were spread out across what is now Belgium.

Fighting Begins: June 15

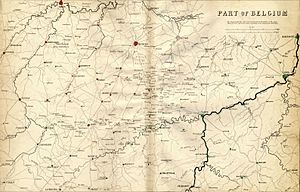

Napoleon moved his 128,000-strong Army of the North secretly to the Belgian border. On June 15, 1815, they crossed the border near Charleroi. The French pushed back the enemy outposts. This put Napoleon in a good "central position" between Wellington's army to the northwest and Blücher's Prussians to the northeast.

Wellington had thought Napoleon would attack through Mons. He worried this would cut off his supplies. Napoleon even sent false information to make Wellington think this. Wellington didn't learn about the capture of Charleroi until late in the afternoon. He ordered his army to gather, but he was still unsure if the attack was real or a trick. He only understood Napoleon's true plan that evening.

The Prussians, however, seemed to know Napoleon's plan better. General Zieten noticed many campfires on June 13, and Blücher began gathering his forces. Napoleon saw the Prussians as the bigger threat. He moved against them first. The Prussian I Corps fought a delaying action on June 15. This gave Blücher time to gather his forces in a strong defensive spot called Sombreffe.

Napoleon sent Marshal Ney to command the French left wing. Ney was ordered to capture the crossroads of Quatre Bras. Wellington was quickly gathering his army there. Ney's scouts reached Quatre Bras that evening.

Key Battles: June 16

Battle of Quatre Bras

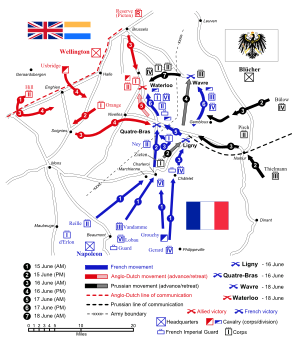

On June 16, Marshal Ney attacked Quatre Bras. It was held by a small number of Dutch troops from Wellington's army. Even though Ney had many more soldiers, he fought carefully and slowly. He failed to capture the crossroads. By the afternoon, Wellington himself took command of the Anglo-allied forces. More and more allied troops arrived throughout the day. The battle ended without a clear winner. The next day, the Allies left Quatre Bras to gather their forces in a better spot closer to Waterloo.

Battle of Ligny

Meanwhile, Napoleon used the right side of his army and his reserves to fight the Prussians at the Battle of Ligny on the same day. The Prussian center broke under heavy French attacks, but their sides held strong. Several Prussian cavalry charges stopped the French from chasing them right away. Napoleon did not pursue the Prussians until the morning of June 18.

A French corps, led by D'Erlon, wandered between both battles. It didn't help much at either Quatre Bras or Ligny. Napoleon wrote to Ney, saying that D'Erlon's wandering had hurt his attacks at Quatre Bras. But Napoleon felt he had Ligny under control without help.

The Day Between: June 17

After the battles on June 16, Ney and Wellington waited for news about what happened at Ligny. Even though the Prussians were defeated, Napoleon still had the advantage. Ney's failure to take Quatre Bras had put Wellington's army in a difficult spot. If Ney, with fresh troops, had attacked Wellington early on June 17, Napoleon could have surrounded Wellington's army.

But this didn't happen. The French were slow after Ligny. Napoleon spent the morning of June 17 having a late breakfast and visiting the battlefield. He then took his reserves and marched with Ney to chase Wellington's Anglo-allied army. He ordered Marshal Grouchy to pursue the Prussians and keep them from reorganizing.

After their defeat at Ligny, the Prussians successfully pulled back. They went northwest to Wavre and regrouped. They left one corps at Wavre to block Grouchy. The other three Prussian corps marched west to attack the French army's right side at Waterloo.

Both Napoleon and Grouchy thought the Prussians were retreating further east. So, on June 17, Grouchy sent most of his cavalry in that direction. By the end of June 17, most of Grouchy's troops were behind the Prussians. This meant they couldn't stop the Prussians from going to Waterloo. They were also too far away to help Napoleon on June 18 if Wellington decided to fight.

When Wellington heard about Blücher's defeat, he organized his army's retreat. He moved them to a place he had chosen a year before. This spot was a gentle hill near the village of Waterloo. It was perfect for his "reverse slope" tactics, where he could hide his troops behind the hill.

Wellington's army successfully pulled back from Quatre Bras, helped by thunderstorms and heavy rain. The French chased them, and there was a small cavalry fight at Genappe. But the French couldn't cause much damage before night fell. Wellington's men settled into camps on the plain of Mont-Saint-Jean.

The Decisive Battle: Waterloo (June 18)

The most important battle of the campaign happened at Waterloo on June 18, 1815. The battle was delayed for several hours because Napoleon waited for the ground to dry after the heavy rain.

By late afternoon, the French army had not managed to push Wellington's forces off the hill where they were positioned. Then, Prussian troops started arriving on the east side of the battlefield. They attacked the French right side in growing numbers. Napoleon's main plan, which was to keep the Coalition armies separated, had failed. His army was defeated and fled the field in confusion.

On the morning of June 18, Napoleon sent orders to Marshal Grouchy. Grouchy was to harass the Prussians and stop them from regrouping. These orders arrived around 6:00 AM. Grouchy's troops started moving at 8:00 AM. By noon, they could hear the cannons from the Battle of Waterloo. Grouchy's commanders told him they should "march to the sound of the guns." But this went against Napoleon's orders. Napoleon had told Grouchy to chase the Prussians through Wavre and then join him. So, Grouchy decided not to take their advice.

It became clear that neither Napoleon nor Grouchy understood that the Prussian army was no longer defeated or disorganized. Any thoughts of joining Napoleon were lost when a second order arrived around 4:00 PM, repeating the same instructions.

The Battle of Wavre (June 18–19)

Following Napoleon's orders, Grouchy attacked the Prussian III Corps near the village of Wavre. Grouchy thought he was fighting the last part of a retreating Prussian army. However, only one Prussian corps remained there. The other three Prussian corps had regrouped after their defeat at Ligny and were marching toward Waterloo.

The next morning, the Battle of Wavre ended in a French victory, but it didn't help Napoleon. Grouchy's part of the army retreated in good order. Other parts of the French army were able to gather around it. However, the army was not strong enough to fight the combined Coalition forces. So, it retreated toward Paris.

Chasing Napoleon: Invasion of France

After the combined victory at Waterloo, Wellington and Blücher decided that the Prussian army, which was less tired, should chase the French. The Anglo-allied army would follow.

The 4,000 Prussian cavalry chased the French throughout the night of June 18. This made the victory at Waterloo even more complete. It also stopped the French from recovering and forced them to leave most of their cannons behind.

A defeated army usually has a rear guard to protect its retreat, but the French had nothing like that. The last of the fleeing soldiers reached the Sambre river by daybreak on June 19. They hoped for a short rest. But Prussian cavalry quickly appeared, and they had to keep fleeing toward Beaumont and Philippeville.

From Charleroi, Napoleon went to Philippeville. He hoped to communicate with Marshal Grouchy, who was still commanding the intact right wing of the army. Napoleon spent four hours sending orders to other generals. He told them to march their troops quickly to Paris. He also told fortress commanders to defend their positions to the very end. He then left for Laon at 2:00 PM.

The French army under Soult retreated to Laon in great confusion. Grouchy's troops, who had reached Dinant, retreated in better order. But they were cut off from the main army and the direct road to Paris. So, Grouchy had to go to Rethel and then Rheims. He tried to quickly join Soult and reach Paris before the Coalition armies.

Meanwhile, Wellington moved quickly into France. Since there was no enemy army to fight, he focused on the fortresses. On June 20, Wellington issued an order to his British army. It told them to treat the French people as if they were allies. Wellington's army generally followed this, paying for food and lodging. This was very different from the Prussian army, whose soldiers treated the French as enemies. They took things from people and destroyed property as they advanced.

From Beaumont, the Prussians advanced to Avesnes, which surrendered on June 21. The French tried to defend it, but a gunpowder storage blew up, killing 400 men. The remaining 439 soldiers surrendered. When the Prussians entered the town, they treated it like a captured enemy city. Their officers even encouraged bad behavior.

Wellington issued a statement to the French people on June 21/22. He explained that his army would be guided by the principles of treating them fairly.

Napoleon arrived in Paris on June 21, three days after Waterloo. He still hoped for a national resistance. But the government and the public did not support this. Napoleon and his brother Lucien were almost alone in thinking they could save France by making Napoleon a dictator. Even the war minister told Napoleon that France's future was with the government. It was clear it was time to protect what was left.

Napoleon finally accepted the truth. On June 22, 1815, he stepped down as emperor. He did this in favor of his four-year-old son, Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte. He knew this was just a formality, as his son was in Austria.

After Napoleon stepped down, a new Provisional Government took over. They appointed Marshal Davout as the army's chief commander. They also started peace talks with the Coalition commanders.

On June 24, British troops captured the town of Cambrai. The governor surrendered the citadel on June 26. Saint-Quentin was left by the French and taken by Blücher. The castle of Guise surrendered to the Prussian army. The Coalition armies, with at least 140,000 soldiers, continued to advance.

The Final Days: Paris Falls

On June 25, Napoleon was told by the new government that he had to leave Paris. He went to Malmaison, the former home of Joséphine.

On June 27, Le Quesnoy surrendered to Wellington's army. The 2,800 soldiers were allowed to go home. On June 26, Péronne was taken by British troops.

By June 29, the Prussians were very close to Paris. They had orders to capture Napoleon, dead or alive. This made Napoleon move west toward Rochefort. He hoped to escape to the United States. But British navy ships were blocking the sea, making escape impossible.

Meanwhile, Wellington continued his advance. As the armies neared Paris, the head of the Provisional Government, Fouché, wrote to Wellington asking him to stop the war.

On June 30, Blücher made a move that decided Paris's fate. He crossed the Seine river downstream from Paris. He moved his entire force to the west-south side of the city. No one had prepared for an enemy attack from that direction.

On July 1, Wellington's army arrived and took positions north of Paris. South of Paris, a French force destroyed a Prussian cavalry group. But this didn't stop the Prussians from moving their whole army to the south side.

By the morning of July 2, Blücher's army was positioned around Meudon and Versailles. This was a huge shock to the French. Even though Wellington's and Blücher's armies were separated, the French couldn't stop them from joining up. The fighting south of Paris on July 2 was tough, but the Prussians succeeded. They took control of the heights of Meudon and the village of Issy. The French lost about 3,000 men that day.

Early on July 3, the French were decisively defeated at the Battle of Issy. This forced them to retreat into Paris. It was clear that no more resistance would work. Paris was now at the mercy of the Coalition armies. The French leaders decided to surrender and ask for an immediate ceasefire.

Representatives from both sides met at Palace of St. Cloud. They agreed to the surrender of Paris under the terms of the Convention of St. Cloud. As agreed, on July 4, the French Army left Paris. On July 6, the Anglo-allied troops occupied parts of Paris on the right side of the Seine. The Prussians occupied the left bank. On July 7, the two Coalition armies entered the center of Paris. The French government bodies ended their meetings.

What Happened Next

On July 8, the French King, Louis XVIII, returned to Paris. People cheered as he took back his throne.

On July 10, the wind was good for Napoleon to sail away from France. But a British fleet appeared, making escape by sea impossible. Unable to stay in France or escape, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of the ship HMS Bellerophon on July 15. He was taken to England. Napoleon was then sent away to the island of Saint Helena, where he died as a prisoner in May 1821.

Some French fortresses did not surrender right away after the government fell. The last one to surrender was Fort de Charlemont, which gave up on September 8.

In November 1815, a formal peace treaty was signed between France and the Seventh Coalition. This Treaty of Paris (1815) was not as kind to France as the previous one. France lost land, had to pay money, and agreed to have an army of occupation in Northern France for at least five years. This army was commanded by the Duke of Wellington.

Timeline of Key Events

| Dates | Synopsis of key events |

|---|---|

| 26 February | Napoleon secretly left Elba. |

| 1 March | Napoleon landed near Antibes. |

| 13 March | European powers declared Napoleon an outlaw. |

| 14 March | Marshal Ney joined Napoleon with 6,000 men. |

| 20 March | Napoleon entered Paris – The start of the One Hundred Days. |

| 25 March | The United Kingdom, Russia, Austria, and Prussia agreed to send 150,000 men each to fight Napoleon. |

| 15 June | French Army of the North crossed into what is now Belgium. |

| 16 June | Napoleon defeated Blücher at the Battle of Ligny. Marshal Ney and Wellington fought at Battle of Quatre Bras, with no clear winner. |

| 18 June | The combined armies of Wellington and Blücher defeated Napoleon's French Army at the Battle of Waterloo. The Battle of Wavre continued until the next day. |

| 21 June | Napoleon arrived back in Paris. |

| 22 June | Napoleon stepped down as emperor. |

| 26 June | Napoleon II was removed from power by the French Provisional Government. |

| 29 June | Napoleon left Paris for western France. |

| 3 July | French asked for a ceasefire after the Battle of Issy. The Convention of St. Cloud (surrender of Paris) ended fighting. |

| 7 July | Prussian and other Coalition forces entered Paris. |

| 8 July | Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne – The end of the One Hundred Days. |

| 15 July | Napoleon surrendered to Captain Maitland of HMS Bellerophon. |

| 16 October | Napoleon was sent away to St Helena. |

| 20 November | Treaty of Paris was signed. |

| 7 December | Marshal Ney was executed in Paris. |

See also

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |