Battle of Ligny facts for kids

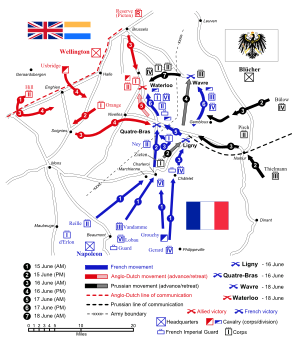

The Battle of Ligny was a major fight that happened on June 16, 1815, near a place called Ligny in what is now Belgium. In this battle, French troops led by Napoleon I fought against a part of the Prussian army, which was commanded by Field Marshal Blücher.

The French won this battle, but it wasn't a complete victory. Most of the Prussian army managed to get away in good order. They were even joined by other Prussian soldiers who hadn't fought at Ligny. Just two days later, these same Prussian troops played a very important role in the famous Battle of Waterloo. The Battle of Ligny was the very last victory Napoleon ever had in his military career.

Quick facts for kids Battle of Ligny |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Seventh Coalition | |||||||

Battle of Ligny, by Théodore Jung |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 68,000-71,000 | 84,000-86,569 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 8,000–11,500 killed, wounded or captured | 16,000 killed or wounded 8,000 captured or missing 27 guns lost |

||||||

Contents

Setting the Stage for Battle

After Napoleon escaped from exile in 1815, the major powers of Europe declared him an outlaw. Countries like the UK, Russia, Austria, and Prussia agreed to send huge armies to stop him.

Napoleon knew he had to act fast. His best chance was to attack the armies already near France before they could join forces. If he could defeat the British and Prussian armies near Brussels, he might be able to win the war.

The British commander, the Duke of Wellington, thought Napoleon would try to sneak around his army. But Napoleon had a different plan. He wanted to split the British and Prussian armies and defeat them one by one. He even sent false information to trick Wellington.

Napoleon secretly moved his army to the border. He divided his forces into three parts: a left wing, a right wing, and a reserve that he led himself. On June 15, the French crossed the border and quickly took control of a key position between Wellington's scattered army and Blücher's Prussian army.

Wellington didn't realize Napoleon's main attack was at Charleroi until late on June 15. He quickly ordered his army to gather near Nivelles and Quatre Bras. Early on June 16, Wellington was at a fancy ball when he got news of Napoleon's fast advance. He rushed his army towards Quatre Bras, where a small force was already trying to hold off the French.

Napoleon saw the Prussian army as the bigger threat, so he decided to attack them first. The Prussians had slowed the French advance on June 15, which gave Blücher time to gather his forces in a strong defensive spot called Sombreffe.

Napoleon's plan for June 16 was to push back the Prussians and then turn his main force to help his left wing defeat Wellington. He wanted to keep the two enemy armies separated and destroy them one after the other.

The Armies Ready for Battle

Napoleon's French army, called the Armee du Nord (Army of the North), was full of experienced soldiers and led by famous generals. Napoleon himself had won many battles. His top commanders, like Marshals Grouchy, Ney, and Soult, were known for their bravery. Most of the French soldiers were veterans who had fought before, but many had never fought together. This meant they didn't always trust each other or their officers. Even so, the French had good equipment and more cavalry (soldiers on horseback) than their enemies.

On the other hand, the Prussian army was still getting organized. Many historians say it was one of the weakest Prussian armies during the Napoleonic Wars. Their cavalry was being rebuilt, and their artillery (cannons) lacked guns and equipment, which were still arriving during the battles. About one-third of the Prussian infantry (foot soldiers) were Landwehr, which were like untrained militia. They often struggled to fight in an organized way. To make things worse, some soldiers from newly joined areas like Saxony and the Rhineland had recently been part of the French army. They weren't very keen to fight against Napoleon, and many even deserted during the battle.

Prussian Defenses

The Prussians weren't completely surprised. They had set up a system of outposts with cavalry and artillery. When the French attacked, the cavalry would quickly ride back to the artillery, which would fire cannons as a signal. This warning system helped the Prussian brigades get ready quickly.

General Zieten's I Corps fought a difficult retreat on June 15. This gave the main Prussian army time to gather at Sombreffe. The Prussians also had a chain of fortified villages and observation posts. Officers made sure messages were sent quickly, and they gathered information by watching the French and questioning civilians. This good intelligence system meant Blücher's headquarters knew about the French movements very early.

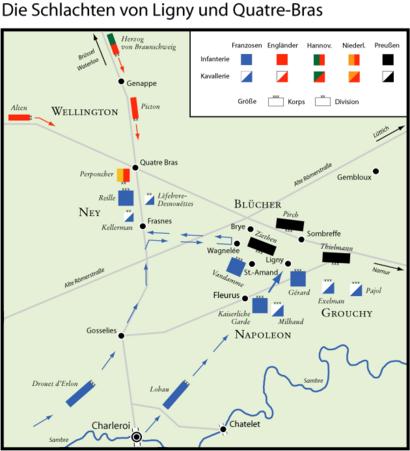

Armies Moving Towards Each Other

On June 15, Napoleon had crossed the Sambre River at Charleroi, putting his army between Wellington and Blücher. His army was in three parts: Marshal Ney on the left, Marshal Grouchy on the right, and Napoleon himself with the main force in the middle. Napoleon's main goal was to keep the two enemy armies apart and defeat them one by one. Ney was to hold Wellington's forces at Quatre Bras. At the same time, French corps under Vandamme and Gérard would attack the Prussians head-on at Ligny. Napoleon planned to use his best troops, the Imperial Guard, to deliver the final blow. This strategy of separating and defeating armies was one of Napoleon's favorite and most successful tactics.

Blücher's Prussian troops included the I, II, and III Corps. The I Corps was at the front, defending villages like Ligny, Brye, and Saint-Amand, with support from the II Corps. The III Corps protected the left side and the escape routes. Blücher and Wellington knew they had to avoid being separated. Wellington even rode to meet Blücher on the morning of the battle and promised to send at least one British corps to help. After their meeting, Wellington left for Quatre Bras.

As the French moved, the Prussian II and III Corps sent more soldiers to help the I Corps. The Prussian front line was very long, and they needed more troops, especially the IV Corps, which was still on its way, and the promised British help.

The Prussians had about 82,700 soldiers facing the French, who had around 60,800 available troops.

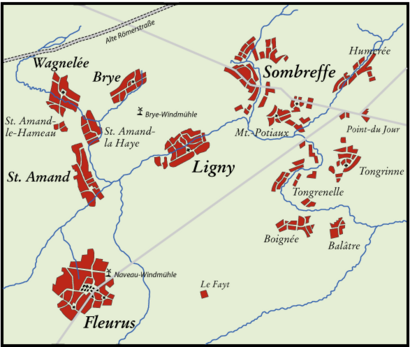

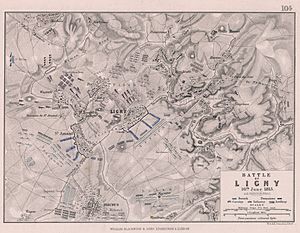

The Ligny Battlefield

The Battle of Ligny took place on land between two rivers, the Scheldt and the Meuse. The Ligny stream was narrow but swampy in places, making the bridges at Saint-Amand and Ligny very important. The villages of Ligny, Saint-Amand, and Wagnelée were strong defensive positions because they were well-built and surrounded by trees. The rest of the battlefield was mostly tall grain fields.

Blücher set up his headquarters at the windmill of Brye, which was on a hill and offered a good view. Napoleon's headquarters were in Fleurus, where he also had a good view from the Naveau windmill.

The Battle Begins

Napoleon waited until about 2:30 PM to attack. He heard cannon fire from Quatre Bras, which meant his left flank was safe. This delay also gave his IV Corps more time to get into position. However, it also meant less time to win a decisive victory before nightfall.

The battle started with a heavy cannon attack from the French Guards' artillery. Soon after, Vandamme's French III Corps attacked the hamlet of Saint-Amand-la-Haye. The Prussian defenders were forced to retreat, but they quickly counter-attacked and took it back. The French attacked again, leading to fierce fighting. The Prussians lost many men and lost Saint-Amand-la-Haye again.

Blücher's right side was in danger, so he ordered more Prussian brigades to retake the hamlet. The fighting was intense, and a French general was badly wounded. The French held the hamlet. Blücher then personally led a counter-attack, and Saint-Amand-la-Haye was back in Prussian hands by 7:00 PM.

At 3:00 PM, Gérard's French IV Corps began fighting around Ligny village itself. Under heavy Prussian cannon fire, a French division managed to capture the church. But they were then hit by intense fire from three sides and had to pull back. Napoleon sent more cannons to support another attack, and the French artillery set many buildings in Ligny on fire. There was brutal house-to-house fighting. Then, a Prussian brigade counter-attacked and recaptured the town.

A Prussian officer later described the terrible situation for the civilians caught in the battle: "Ligny was half on fire... we found two old people, a man and a woman, sitting dazed at the hearth, without moving... they could not be convinced to move from their home."

A Missed Opportunity

Around 5:00 PM, Blücher sent his fresh II Corps into the battle. At the same time, on the French left, Vandamme saw a large force of 20,000 to 30,000 men approaching. He mistakenly thought they were enemy troops. Napoleon was surprised by this news because he had ordered Marshal Ney to send a French corps (d'Erlon's I Corps) to attack the Prussian rear.

What happened was that d'Erlon's corps was marching towards Ligny, as Napoleon had ordered. But Marshal Ney, who didn't know about Napoleon's new orders, told d'Erlon to turn around and march back to Quatre Bras. So, d'Erlon's I Corps, which could have made a big difference, ended up marching back and forth and didn't fight in either battle that day. This was a huge missed chance for Napoleon.

Blücher tried to use this French confusion to his advantage, ordering an attack on the French left. But French reinforcements arrived, and the Prussians were pushed back to their original positions.

Prussian Counter-Attack

By 7:00 PM, the fighting was still intense. Blücher received news that Wellington was heavily busy fighting Ney's army and couldn't send help to Ligny. So, Blücher decided to launch a counter-attack on the French left flank. He strengthened his tired troops in Ligny, gathered his last reserves, and personally led an attack on Saint-Amand. The attack was successful at first, but then it slowed down. The French Imperial Guard counter-attacked, and the Prussians began to retreat in a messy way.

Napoleon's Final Push

Seeing the Prussians retreating, Napoleon decided it was time for his decisive move. He knew he couldn't completely destroy the Prussian army, but he could make them unable to fight seriously the next day. More French troops arrived. The Guard's artillery began firing heavily on the Prussian center. After a thunderstorm, the cannons opened fire again.

Around 7:45 PM, 60 cannons fired a huge salvo, signaling a combined attack by Gérard's corps and the famous Old Guard, supported by cavalry. The French Guard met strong resistance at first, but the tired Prussian soldiers couldn't stand against Napoleon's best troops. Around 8:30 PM, the Prussian center at Ligny was overwhelmed.

The Prussians formed a new defensive line about 1 kilometer behind Ligny. Units from their I and II Corps retreated to this new position, fighting off French attacks as they went. Even though they were forced to leave Ligny, the Prussian infantry retreated in good order, forming squares and bravely fighting off cavalry attacks.

Blücher is Injured

During the Old Guard's attack, Blücher personally led a cavalry counter-attack. The 72-year-old Blücher's horse was shot and fell on him, leaving him semi-conscious. He was rescued from the field. While Blücher was being helped, the French cavalry defeated the Prussian counter-attack. Blücher's Chief of Staff, August von Gneisenau, took over command.

The Prussian Retreat

There are different stories about what Gneisenau decided to do next. Some say he chose to retreat north to stay close to Wellington. Others say he was angry about the lack of British support and initially wanted to retreat east. However, Blücher, once he was found alive, insisted on staying in command. He told his British liaison officer that they would join Wellington. This decision by Blücher was very important. Instead of retreating far away, he chose to move towards Wellington, even if it meant abandoning his own supply lines. The battle had not completely broken the Prussian army; they had lost only about one-sixth of their force. With nearly 100,000 men, they could still help Wellington turn the tide.

Around 10:00 PM, the order to retreat was given. The Prussian right and center retreated slowly and in good order, leaving a small force behind to slow any French pursuit. They regrouped about a quarter of a league (about 1 km) from the battlefield and then continued their retreat towards Wavre, without being chased by the French.

The Prussian III Corps, which was mostly unharmed, retreated last towards Gembloux, where the IV Corps was waiting. They left a strong rear-guard behind. The last Prussian units left the battlefield at daybreak on June 17, as the exhausted French didn't press their attack.

The IV Corps, which hadn't fought at Ligny, moved to a strong position south of Wavre, where the rest of the Prussian army could gather. Blücher was already in touch with Wellington, promising to bring his entire army to help. This shows how little the Battle of Ligny had truly weakened the Prussian army's spirit.

One historian noted that Ligny was a battle where 78,000 men lost to 75,000, but it wasn't a glorious victory for the French. They only captured 21 cannons and a few thousand prisoners. About 8,000 Prussian troops, mostly new recruits, fled to other cities.

What Happened Next

The Prussian retreat was not stopped, and seemingly not even noticed, by the French. Crucially, they retreated north, parallel to Wellington's path, and stayed in contact with him. They regrouped near Wavre, about 8 kilometers east of Waterloo. From there, they marched to Waterloo on June 18.

Wellington expected Napoleon to attack him at Quatre Bras. So, on June 17, he retreated north to a strong defensive position he had scouted earlier, a low ridge south of Waterloo village. Napoleon started late on June 17 and joined Ney at Quatre Bras, but found only Wellington's cavalry rear-guard. The French chased Wellington to Waterloo, but only managed to defeat a small cavalry group before heavy rain started for the night. By the end of June 17, both armies were in position for the decisive Battle of Waterloo on June 18, 1815.

Before leaving Ligny, Napoleon gave Grouchy 33,000 men and ordered him to follow the retreating Prussians. But Grouchy started late, wasn't sure where the Prussians had gone, and his orders were unclear. Because of this, he was too late to stop the Prussian army from reaching Wavre. From Wavre, Blücher could march to help Wellington at Waterloo, while Grouchy's forces fought a separate battle at Wavre.

After the French lost at Waterloo, only Grouchy managed to retreat back to France with his army of nearly 30,000 soldiers. However, this army wasn't strong enough to fight the combined enemy forces. Napoleon gave up his power on June 24, 1815, and finally surrendered on July 15.

See also

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |