Gaspard Monge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

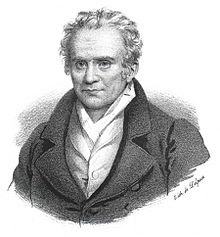

Gaspard Monge

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 9 May 1746 |

| Died | 28 July 1818 (aged 72) Paris, France

|

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Descriptive geometry Transportation theory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | mathematics, engineering, education |

| Notable students | Jean-Baptiste Biot Charles Dupin Sylvestre François Lacroix Jean-Victor Poncelet |

Gaspard Monge (born May 9, 1746 – died July 28, 1818) was a brilliant French mathematician. He is often called the inventor of descriptive geometry, which is the math behind technical drawing. He also helped create differential geometry. During the French Revolution, he was a government minister. He also played a big part in changing France's education system. He even helped start the famous École Polytechnique university.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Education

Gaspard Monge was born in Beaune, France. His father was a merchant. He went to school with the Oratorians in Beaune. In 1762, he moved to another college in Lyon. Just one year later, at only seventeen, he became a physics teacher there.

After finishing his studies in 1764, Monge returned to Beaune. He created a large, detailed map of the town. He even invented new ways to observe and measure things for his map. He also built the tools he needed. This map is still kept in the town's library today. An army engineer saw his work and was very impressed. This engineer recommended Monge for a job as a draftsman at a special engineering school. Many people believe Monge's work helped start the field of engineering drawing.

Developing His Skills

At the Royal School, only people from noble families could become officers. Monge was not from a noble family, so he could not join the main program. However, his amazing drawing skills were highly valued. He used his free time to work on his own ideas. He met Charles Bossut, a math professor at the school. Monge later said he was often tempted to give up. He felt his drawing skills were appreciated, but his deeper math talents were not.

After a year, Monge was asked to design a fortification. He needed to make it as strong as possible. The usual way to do this involved long, difficult calculations. But Monge found a new way to solve the problem using drawings. At first, his solution was not accepted. It was too fast! But when they looked closely, they saw how valuable his work was. Everyone then recognized Monge's special abilities.

In 1769, Monge took over Bossut's job as a math professor. In 1770, he also became a professor of experimental physics.

Later Career and Family

In 1777, Monge married Cathérine Huart. She owned a metal workshop. This made Monge interested in metallurgy, which is the study of metals. In 1780, he became a member of the French Academy of Sciences. He also became good friends with the famous chemist C. L. Berthollet.

In 1783, Monge became an examiner for naval students. He was asked to write a full math textbook. But he refused. He knew that writing a new book would hurt the income of a widow whose husband had written the old textbooks. In 1786, Monge published his own book called Traité élémentaire de la statique.

The French Revolution and Beyond

The French Revolution completely changed Monge's life. He strongly supported the Revolution. In 1792, he became the Minister of the Marine. This meant he was in charge of the navy. He held this job for about eight months.

When the government asked scientists to help defend the country, Monge worked very hard. He wrote books on how to make cannons and how to make steel. He also played a key role in setting up new schools. He helped create the Ecole Normale and the school for public works, which later became the famous École Polytechnique. At both schools, he taught descriptive geometry. His lectures from 1795 were published as Géométrie descriptive in 1799.

From 1796 to 1797, Monge traveled to Italy. He was with C.L. Berthollet and some artists. Their job was to select important paintings and sculptures from Italy for France. While there, he became good friends with Napoleon Bonaparte. When he returned to France, Monge became the Director of the École Polytechnique.

In 1798, Monge went back to Italy for another mission. Then, he joined Napoleon's trip to Egypt. He worked with Berthollet on scientific projects there. They both returned to France with Napoleon in 1798. Monge continued his work at the École Polytechnique. He was given a high position in the government and the title of Count of Pelusium. However, after Napoleon lost power, Monge lost all his honors. He was even removed from the list of members of the Institute.

Napoleon Bonaparte once said that Monge did not believe in God. Monge was first buried in a special tomb in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Later, his remains were moved to the Panthéon in Paris, a famous building where many great French people are buried.

A

was built in his honor in Beaune in 1849. Monge's name is also one of the 72 names written on the base of the Eiffel Tower. Since 1992, the French Navy has a ship named Monge after him.

His Important Work

Between 1770 and 1790, Monge wrote many papers on math and physics. One important paper was "Sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais" (about the theory of earthworks). In this paper, he explored how to move earth most efficiently. This work led to his discovery of "curves of curvature" on a surface. He also suggested an early idea about how our eyes see colors consistently, even when the light changes.

Monge's 1781 paper is also seen as an early idea for "linear optimization" problems. This includes the "transportation problem". This problem is about finding the best way to move things from one place to another. His ideas have been rediscovered and used by many mathematicians since then.

Another of his papers from 1783 discussed how water is made when hydrogen burns.

Selected Publications

- 1781: Mémoire sur la théorie des déblais et des remblais (A paper on the theory of earthworks)

- 1793: (with Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde and Claude-Louis Berthollet) Avis aux ouvriers en fer, sur la fabrication de l'acier. Tome 8 (Advice to ironworkers, on making steel)

- 1794: Description de l'art de fabriquer des canons (Description of the art of making cannons)

- 1795: Application d'analyse à la géométrie (Application of analysis to geometry)

- 1799: Géométrie descriptive. Leçons données aux écoles normales (Descriptive Geometry. Lessons given at the normal schools)

- 1807: Application de l'analyse à la géométrie, à l'usage de l'Ecole impériale polytechnique.

- 1810: (with Jean Nicolas Pierre Hachette) Traité élémentaire de statique, a l'usage des écoles de la Marine (Elementary treatise on statics, for naval schools)

See also

In Spanish: Gaspard Monge para niños

In Spanish: Gaspard Monge para niños

- History of the metre

- Monge array

- Monge cone

- Monge equation

- Monge patch

- Monge point

- Monge–Ampère equation

- Monge's theorem

- Clebsch representation

- Earth mover's distance

- Seconds pendulum

- Transportation theory

Images for kids

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |