Benjamin Lee Whorf facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benjamin Lee Whorf

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | April 24, 1897 Winthrop, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Died | July 26, 1941 (aged 44) Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Known for | Sapir–Whorf hypothesis (Linguistic relativity), Nahuatl linguistics, allophone, cryptotype, Maya script |

| Spouse(s) |

Celia Inez Peckham

(m. 1920) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Mike Whorf (nephew) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | linguistics, anthropology, fire prevention |

| Institutions | Hartford Fire Insurance Company, Yale University |

| Influences | Wilhelm von Humboldt, Fabre d'Olivet, Edward Sapir, Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell, C. K. Ogden, Madame Blavatsky |

| Influenced | George Lakoff, John A. Lucy, Michael Silverstein, Linguistic Anthropology, M.A.K. Halliday |

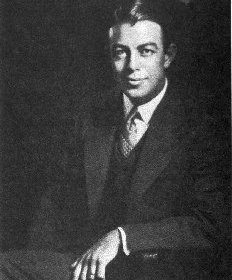

Benjamin Lee Whorf (born April 24, 1897 – died July 26, 1941) was an American linguist and fire prevention engineer. He is famous for the "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis." This idea suggests that the language we speak shapes how we see and understand the world.

The idea was named after Whorf and his teacher, Edward Sapir. Whorf first called it linguistic relativity. He thought it was similar to Einstein’s idea of physical relativity. Whorf believed that language acts like a frame of reference for how we observe things.

Even though he worked as a chemical engineer, Whorf loved studying languages. He started by looking at Biblical Hebrew. Soon, he began studying the ancient languages of Mesoamerica on his own. Experts were very impressed with his work. In 1930, he received a grant to study the Nahuatl language in Mexico.

After his trip, he started studying linguistics with Edward Sapir at Yale University. He still kept his job at the Hartford Fire Insurance Company. At Yale, he studied the Hopi language and the history of Uto-Aztecan languages. He wrote many important papers.

Whorf died from cancer in 1941. His friends, who were also linguists, published many of his writings after his death. In the 1960s, some scholars criticized Whorf's ideas. They thought language structure was more about universal human thinking than cultural differences.

However, in the late 1900s, interest in Whorf's ideas grew again. New scholars argued that earlier criticisms didn't fully understand his work. Today, studying linguistic relativity is still an active area of research. It creates debates between those who believe language shapes thought and those who believe in universal thinking patterns. Whorf's other ideas, like the allophone and the cryptotype, are widely accepted in linguistics.

Biography

Early Life and Family

Benjamin Lee Whorf was born on April 24, 1897, in Winthrop, Massachusetts. His father, Harry Church Whorf, was an artist and designer. Benjamin had two younger brothers, John and Richard. Both became well-known artists. John was a famous painter, and Richard was an actor and TV director.

Benjamin was the most academic of the brothers. From a young age, he loved science and reading. He read about botany, astrology, and ancient Middle American history. He even kept a detailed diary of his thoughts and dreams.

Career in Fire Prevention

Whorf graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1918. He earned a degree in chemical engineering. In 1920, he married Celia Inez Peckham. They had three children: Raymond Ben, Robert Peckham, and Celia Lee.

Around the same time, he started working as a fire prevention engineer for the Hartford Fire Insurance Company. He was very good at his job. He traveled to factories to inspect them for fire risks. One story tells how he figured out a secret chemical process just by knowing what a plant produced. He told the director, "You couldn't do it in any other way."

Whorf also used his job to show how language affects behavior. He noticed that workers handled "empty" gasoline drums less carefully than full ones. They even smoked near the "empty" drums. But Whorf knew the "empty" drums were more dangerous because they contained flammable vapor. He argued that calling them "empty" made workers think they were safe.

Early Interest in Languages

Whorf was a spiritual person. He was very interested in theosophy. This is a group based on Buddhist and Hindu teachings. It promotes the idea that the world is connected and that all people are united. Whorf felt that people in theosophy were very open to new ideas.

Around 1924, Whorf became interested in linguistics. He started by studying old Biblical texts. He wanted to find hidden meanings in them. He also began to study Biblical Hebrew and ancient Maya texts.

Self-Taught in Mesoamerican Languages

Whorf studied languages mostly at the Watkinson Library in Hartford. This library had many books on Native American languages. There, he met a young boy named John Bissell Carroll. Carroll later published many of Whorf's essays in a book called Language, Thought and Reality.

Whorf became very interested in ancient Mesoamerica. He started studying the Nahuatl language in 1925. Later, in 1928, he began studying Maya hieroglyphic texts. He quickly became skilled in these areas. He even started talking with famous Mesoamerican experts.

In 1928, he gave his first paper at a big conference. He presented his translation of a Nahuatl document. He also started comparing Uto-Aztecan languages. Edward Sapir had recently shown these languages were related.

Field Studies in Mexico

Because of his promising work, experts suggested Whorf apply for a grant. He used the money to travel to Mexico City in 1930. There, he met speakers of Nahuatl. He studied their language directly.

His trip resulted in a detailed description of the Milpa Alta dialect of Nahuatl. This work was published after his death. He also wrote about Aztec pictograms found at a monument. He noted how Aztec and Maya symbols were similar in meaning.

Studying at Yale University

Even though Whorf had taught himself linguistics, he was already known in the field. He met Sapir, a leading U.S. linguist. In 1931, Sapir moved to Yale University. Sapir was very impressed with Whorf's work.

Whorf took Sapir's first course on "American Indian Linguistics." He enrolled in a graduate program but never got a degree. He was happy to be part of the intellectual group around Sapir. Whorf became a central and respected student among Sapir's group.

Sapir greatly influenced Whorf's ideas. Sapir believed that language could hide or make it harder to see the world as it truly is. Whorf adopted this idea. He thought that true understanding came from careful study of language.

Work on Hopi and Language Structure

Sapir encouraged Whorf to continue his work on Uto-Aztecan languages. Whorf published several articles on this topic. He became especially interested in the Hopi language. He worked with Ernest Naquayouma, a Hopi speaker, to learn about the language. In 1938, Whorf even took a short trip to a Hopi village in Arizona.

In 1936, Yale made Whorf an Honorary Research Fellow in Anthropology. He also taught anthropology lectures at Yale, filling in for Sapir when he was ill. Whorf made important contributions to language theory. He introduced the idea of the allophone. This describes how different sounds can be treated as the same sound in a language. He also developed the concept of "covert grammatical categories," which are hidden patterns in grammar.

Final Years and Ideas

In late 1938, Whorf's health declined due to cancer. He was also deeply saddened by Sapir's death in 1939. In his last two years, he focused on his ideas about linguistic relativity. His 1939 article, "The Relation of Habitual Thought And Behavior to Language," is his most famous work on this topic.

He also wrote articles for the MIT Technology Review. In these writings, he suggested that non-European languages sometimes describe the world in ways that are more accurate than European languages. He believed that science should pay attention to how language shapes our understanding of reality. Whorf argued that European languages often focus on fixed things, while other languages focus more on processes and changes. He thought that studying other languages could help scientists see the world in new ways.

Whorf's Main Work

Linguistic Relativity

Whorf is best known for his idea of linguistic relativity. It is often called the "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis." Whorf never wrote it as a formal hypothesis. But his examples of how language grammar affects how people think led to much research. This research is now called "Sapir–Whorf studies."

How Language Shapes Thought

Whorf and Sapir were influenced by Albert Einstein's relativity theory. They thought language provides a "frame of reference" for our observations. For example, people speaking different languages might hear sounds differently. This shows how language guides our attention and perception.

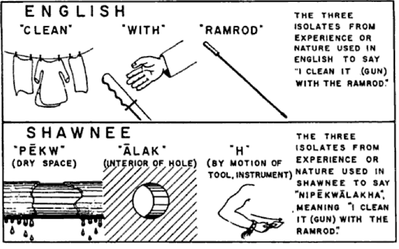

Whorf also used ideas from gestalt psychology. He believed languages make speakers describe the same events in different ways. He called these "isolates from experience." For instance, cleaning a gun is described differently in English and Shawnee. English focuses on the gun and the cleaning. Shawnee focuses on the movement of making a dry space in a hole. The event is the same, but the language makes us pay attention to different parts.

How Much Does Language Influence Us?

Some of Whorf's writings might seem to suggest that language completely controls our thoughts. This idea is called linguistic determinism. However, many scholars now argue that Whorf meant that language shapes how we talk about the world, not necessarily how we think about it.

Whorf noted that to share thoughts, we must use the categories of our language. This means we fit our experiences into the language's shape. He said, "No individual is free to describe nature with absolute impartiality." He believed language guides our attention. It makes us focus on certain things and overlook others.

The Hopi Time Debate

Whorf's study of Hopi time is his most discussed example of linguistic relativity. He argued that the Hopi people's understanding of time is different from English speakers. He said the Hopi language does not treat time as separate, countable units like "three days." Instead, it sees time as a continuous process. Because of this, he claimed the language lacked nouns for units of time.

In his 1939 essay, Whorf wrote that the Hopi language had "no words, grammatical forms, construction or expressions that refer directly to what we call 'time'."

However, linguist Ekkehart Malotki later challenged Whorf's ideas. Malotki showed many examples of how the Hopi language does refer to time. He argued that Hopi tenses combine past and present into one category, while future is separate.

Despite the criticism, some scholars defended Whorf. They argued that Whorf's point was not that Hopi lacked words for time. Instead, he meant that the Hopi concept of time was fundamentally different from European ideas. Whorf described how Hopi tenses refer to events that have happened or are happening, and events that have not yet happened. He also noted many words that describe aspects of time without counting units.

Contributions to Language Theory

Whorf's ideas about "overt" (obvious) and "covert" (hidden) grammatical categories have been very important in linguistics. British linguist Michael Halliday said Whorf's idea of the "cryptotype" (hidden grammar patterns) was one of the biggest contributions to 20th-century linguistics.

Whorf also introduced the term allophone. This describes different ways a single sound (phoneme) can be pronounced in a language. For example, the 'p' sound in "pin" is different from the 'p' sound in "spin." But English speakers hear them as the same 'p'. Whorf saw allophones as another example of linguistic relativity. He said that what a language makes "like" is like, and what it makes "unlike" is unlike.

Whorf was very interested in metalinguistics. This is the study of how speakers become aware of their own language. Whorf believed that understanding how language affects our experience could help us describe the world more accurately. His ideas have influenced the study of metalinguistic awareness in linguistic anthropology.

Studies of Uto-Aztecan Languages

Whorf did important work on the Uto-Aztecan languages. These languages were shown to be a family by Sapir in 1915. Whorf first studied Nahuatl, Tepecano, and Tohono O'odham. At Yale, he published several articles on Uto-Aztecan linguistics. His work helped strengthen the study of these languages.

The first Native American language Whorf studied was Nahuatl. He first learned it from old books. Later, he did his first field work in Mexico in 1930. Whorf believed Nahuatl was an oligosynthetic language. This is a type of language he described where words are built from a few basic parts.

His detailed description of the Milpa Alta dialect of Nahuatl was published after his death. It became a key resource for scholars. Although his writing could be complex, his work was seen as very advanced. He also analyzed the sounds of these dialects.

One of Whorf's achievements in Uto-Aztecan linguistics was explaining why Nahuatl has the sound /tɬ/. This sound is not found in other languages of the family. In 1937, Whorf argued that this sound came from an older */t/ sound changing to [tɬ] before */a/. This sound change is known as "Whorf's law." It is still considered valid today.

Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

In the 1930s, Whorf published studies arguing that Mayan writing was partly phonetic (based on sounds). While some scholars supported him, the main expert on ancient Maya, J. E. S. Thompson, strongly disagreed. Thompson believed Mayan writing had no phonetic parts and could not be deciphered by studying its sounds.

Whorf argued that not using linguistic analysis of Maya languages was holding back the decipherment. Whorf looked for sound clues within the symbols. He didn't realize the system used both pictures and syllables. Even though his approach was not exactly right, his main idea that the script was phonetic was later proven true. This happened when Yuri Knorozov successfully deciphered Mayan writing in the 1950s using a syllabic approach.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Benjamin Lee Whorf para niños

In Spanish: Benjamin Lee Whorf para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |