Linguistic relativity facts for kids

The idea of linguistic relativity is super interesting! It's also known as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis. This idea suggests that the language you speak can actually change how you see the world and how you think. So, your language might shape how you understand things around you.

This idea has been debated a lot. There are different versions of it. The strong hypothesis says that language completely controls your thoughts. It suggests that your language limits what you can think. Most modern experts agree this strong version isn't true.

However, there's a weaker version. This one says that your language influences and shapes your thoughts. It doesn't strictly limit them. Many studies have found evidence supporting this weaker idea.

The name "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis" can be a bit confusing. That's because Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf never wrote a book together. They also never formally called their ideas a "hypothesis." The difference between the strong and weak versions also came later. But their writings often hinted at these stronger or weaker ideas.

The link between language and thought is studied in many fields. These include philosophy, psychology, and anthropology. This idea has even inspired stories and made-up languages!

Contents

- A Look Back: History of the Idea

- How Language Affects Color Words

- Universalism: Language is the Same for Everyone

- Cognitive Linguistics: A New Look

- How Research Has Changed

- Other Areas of Influence

- Images for kids

- See also

A Look Back: History of the Idea

The idea that language and thought are connected isn't new. Thinkers in the 1800s, like Wilhelm von Humboldt, talked about it. They saw language as showing the spirit of a nation.

Early 1900s American anthropologists, like Franz Boas and Edward Sapir, also explored this. But Sapir often wrote against the idea that language completely controls thought.

Sapir's student, Benjamin Lee Whorf, became well-known for his ideas. He wrote about how language differences seemed to affect how people thought and acted. Another student of Sapir, Harry Hoijer, first used the term "Sapir–Whorf hypothesis."

Later, in the 1950s, Roger Brown and Eric Lenneberg turned Whorf's ideas into something they could test. They did experiments to see if people who spoke different languages saw colors differently.

In the 1960s, many linguists focused on what all human languages have in common. Because of this, the idea of linguistic relativity became less popular.

But from the late 1980s, new researchers started looking at it again. They found support for the weaker versions of the idea. They showed that language can influence some parts of our thinking. Today, most linguists agree that language does influence certain thought processes. But it doesn't control everything.

Ancient Ideas to the Enlightenment

The idea that language and thought are linked is very old. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato wondered if our understanding of reality is built into language. But Plato also suggested that true reality might be beyond words.

Later, thinkers like St. Augustine believed language was just a way to label ideas we already had. This view was common for a long time. Immanuel Kant thought language was just one tool humans use to understand the world.

German Romantic Thinkers

In the late 1700s and early 1800s, German thinkers explored the idea of different national characters. They believed a nation's spirit was shown in its language.

Johann Georg Hamann

Johann Georg Hamann was one of the first to talk about the "genius of a language." He suggested that a people's language affects their worldview. He said, "The lines of their language will thus match the direction of their thinking."

Wilhelm von Humboldt

In 1820, Wilhelm von Humboldt linked language study to national identity. He suggested that thoughts are like an inner conversation using your native language's grammar. He believed a nation's worldview was truly shown in its language.

Humboldt thought languages like German and English were "most perfect." He felt this explained why their speakers were dominant. He famously said, "The diversity of languages is not a diversity of signs and sounds but a diversity of views of the world."

Humboldt believed each language creates a person's worldview. It does this through its words, grammar, and how it organizes ideas.

Boas and Sapir's Contributions

In the early 1900s, many people thought some languages were better than others. They believed "lesser" languages kept their speakers from thinking well. William Dwight Whitney, an American linguist, even wanted to get rid of Native American languages. He thought their speakers would be better off learning English.

Franz Boas was the first to challenge this view. He was an anthropologist who studied the Inuit people. Boas believed all cultures and languages were equally valuable. He said there was no such thing as a "primitive" language. All languages could express the same ideas, even if in different ways. Boas saw language as a key part of culture. He insisted that researchers learn the local language to understand a culture.

Boas wrote, "It does not seem likely... that there is any direct relation between the culture of a tribe and the language they speak." He meant that language shapes culture, but culture isn't limited by language.

Boas' student, Edward Sapir, went back to Humboldt's idea. Sapir thought languages held the key to understanding people's worldviews. He believed that because languages have different grammar systems, no two languages are exactly alike. This meant that speakers of different languages might see reality differently.

Sapir said, "No two languages are ever similar enough to be considered as representing the same social reality." He believed that different societies live in different worlds, not just the same world with different labels.

However, Sapir also clearly rejected the strong idea that language completely controls thought. He stated, "It would be naive to imagine that any analysis of experience is dependent on pattern expressed in language."

Sapir also pointed out that language and culture are not always linked. He noted that unrelated languages can share a culture. And closely related languages can belong to different cultures. He gave examples from Native American languages. He also observed that a common language, like English in England and America, doesn't always lead to a common culture. Other factors can be stronger.

Sapir didn't directly study how languages affect thought. But his ideas about linguistic relativity were important. They were later picked up by Whorf.

Benjamin Lee Whorf's Ideas

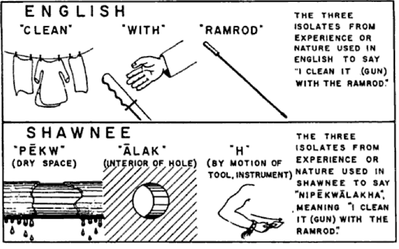

Benjamin Lee Whorf is most linked to the "linguistic relativity principle." He studied Native American languages. He tried to explain how grammar and language use affected how people saw things.

Whorf's ideas are still debated. Some critics say he believed in a strong language control over thought. But others say Whorf clearly said that translation between languages is possible.

Critics also said Whorf wasn't clear enough about how language influences thought. They felt he didn't prove his ideas. Most of his arguments were stories and guesses. He tried to show how "exotic" grammar was linked to "exotic" ways of thinking.

Whorf famously said, "We cut nature up, organize it into concepts, and give them meaning... largely because we are part of an agreement to organize it this way." He believed this agreement happens in our language. He thought that people with different language backgrounds see the universe differently.

Many Words for One Concept

One of Whorf's famous examples of linguistic relativity involved words for snow. He claimed the Inuit language had many words for snow. European languages, which he called "Standard Average European" (SAE), had only one. This example was later questioned as a misunderstanding.

Another example was the Hopi language's words for water. One word was for drinking water in a container. Another was for a natural body of water.

These examples showed that some languages make more specific differences in meaning. They also showed that direct translation of simple ideas, like snow or water, isn't always easy.

Whorf also had an example from his job as a fire inspector. He saw a chemical plant with two storage rooms for gasoline barrels. One was for full barrels, one for empty ones. Workers didn't smoke near full barrels. But they smoked near "empty" barrels. This was dangerous because empty barrels still had flammable fumes. Whorf thought the word empty made workers think the barrels were harmless. This example was later criticized. Critics said it didn't prove language caused the smoking.

Time in Hopi

Whorf's most detailed argument was about how the Hopi people understood time. He believed that unlike English, Hopi didn't see time as separate, countable moments. For example, they wouldn't say "three days." Instead, they saw time as a continuous process. He thought this view of time was central to Hopi culture.

Later, Ekkehart Malotki claimed he found no evidence for Whorf's ideas about Hopi time. Malotki used old documents and modern speech. He concluded that Hopi people did not think about time the way Whorf suggested.

However, some researchers like John A. Lucy criticized Malotki's study. They said he misunderstood Whorf's claims. They also said he forced Hopi grammar into a model that didn't fit.

How Language Structure Affects Thought

Whorf's argument about Hopi time is an example of a "structure-centered" approach. This means starting with a language's unique grammar. Then, you look at how it might affect thought and behavior.

More recent research uses this approach. For example, Lucy studied the Mayan language Yucatec. He found that Yucatec speakers group objects by their material. English speakers, however, group them by their shape. This is because of differences in how the languages use grammatical numbers and classifiers.

Some philosophers, like Donald Davidson, have argued that Whorf's Hopi examples actually disprove his point. They say Whorf had to translate Hopi terms into English to explain them. This shows they *can* be translated.

Whorf's Legacy

Whorf died in 1941 at age 44. He left many papers unpublished. Other linguists continued his work. His most important writings on linguistic relativity were published in 1956. The book was called Language, Thought and Reality.

Brown and Lenneberg's Experiments

In 1953, Eric Lenneberg criticized Whorf. Lenneberg believed languages mainly describe the real world. He thought that even if languages express ideas differently, the meanings are the same. He argued that Whorf's English descriptions of Hopi time were just translations. This, he felt, disproved linguistic relativity.

However, Whorf was more interested in how the habitual use of language affects daily behavior. He meant that English speakers could *understand* how a Hopi speaker thinks. But they don't *think* that way themselves.

Lenneberg's main criticism was that Whorf never showed a clear link between language and thought. With Brown, Lenneberg suggested that proving this link needed experiments. They published their findings in 1954.

Since Sapir and Whorf never wrote a formal hypothesis, Brown and Lenneberg made their own. They said:

- Different languages lead to different ways of experiencing and understanding the world.

- Language causes a certain way of thinking.

Brown later made these into "weak" and "strong" ideas:

- Differences in language systems will generally match differences in how people think.

- Your native language strongly influences or completely decides your worldview.

Brown's ideas became well-known. They were often mistakenly linked to Whorf and Sapir. But the second idea, that language completely controls thought, was never truly supported by Sapir or Whorf.

Joshua Fishman's "Whorfianism of the Third Kind"

Joshua Fishman believed Whorf's true ideas were missed. In 1982, he suggested "Whorfianism of the third kind." He said Whorf was really interested in the value of "little peoples" and "little languages."

Whorf had criticized "Basic English," a simplified version of English. He said, "To limit thinking to the patterns of English... is to lose a power of thought which, once lost, can never be regained." He believed that knowing many languages helps us think better.

Brown's weak idea says language influences thought. The strong idea says language determines thought. Fishman's "Whorfianism of the third kind" says language is a key to culture.

New Research: Rethinking Linguistic Relativity

In 1996, a book called Rethinking Linguistic Relativity was published. It started a new era of studies. These studies looked at how language affects our minds and social life.

The book included studies on how different languages describe space. Stephen C. Levinson found that people speaking the Guugu Yimithirr language in Australia use compass directions (north, south, east, west) for everything. An English speaker might say "in front of the house." A Guugu Yimithirr speaker would say "north of the house." This shows how language shapes how we think about location.

Researchers like Dan Slobin described "thinking for speaking." This is how our perceptions and pre-language thoughts are put into words for communication. Slobin argued that these are the kinds of thought processes where linguistic relativity happens.

How Language Affects Color Words

Color words have been a big area of study for linguistic relativity.

Brown and Lenneberg's Color Studies

Brown and Lenneberg believed that the real world is the same for everyone. But they wanted to see if different languages describing colors differently would affect behavior.

They did experiments with colors. First, they checked if English speakers remembered colors better if they had a specific name for them. Then, they asked English and Zuni speakers to recognize colors. Zuni speakers group green and blue together as one color. Brown and Lenneberg found that Zuni speakers had trouble recognizing small differences within the green/blue category.

This study showed that language categories could affect how people recognize colors. However, later research found that color perception is partly "hardwired" into our brains. This means it's more universal than other areas of language.

Berlin and Kay's Color Research

Berlin and Kay continued color research. They found that even though languages have different color words, they follow universal patterns. For example, languages with only three color terms always have black, white, and red.

This finding was seen as a strong argument against linguistic relativity. It suggested that color naming wasn't random. However, relativists like Lucy later criticized Berlin and Kay. They said Berlin and Kay only looked at color terms that *only* described color. This made them miss other ways color terms might show linguistic relativity.

Universalism: Language is the Same for Everyone

Universalist scholars disagreed with linguistic relativity. Lenneberg helped develop the idea of Universal Grammar. This idea, made popular by Chomsky, says all languages share the same basic structure.

The Chomsky school believed that language structures are mostly inborn. They thought differences between languages were just on the surface. They didn't affect the brain's universal thinking processes. This became the main idea in American linguistics from the 1960s to the 1980s. During this time, linguistic relativity was often made fun of.

Steven Pinker's View

Today, many universalists still oppose linguistic relativity. For example, Steven Pinker argues that thought is separate from language. He believes language itself isn't essential to human thought. He even suggests we don't think in "natural" languages. Instead, we think in a "mentalese," a language of thought before any spoken language. Pinker strongly criticizes Whorf's ideas.

However, relativists accuse Pinker and other universalists of misrepresenting Whorf's views. They say Pinker argues against ideas Whorf never actually held.

Cognitive Linguistics: A New Look

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, new ideas in cognitive psychology and cognitive linguistics brought back interest in the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis.

George Lakoff was one of these researchers. He argued that language often uses metaphors. Different languages use different "cultural metaphors." These metaphors show how speakers of that language think. For example, English talks about time like it's money. We "save time" or "spend time." Other languages don't do this.

Lakoff also noted that some metaphors are common across many languages. For example, "up" often means "good," and "down" means "bad." This is because they are based on common human experiences.

Recent research supports the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. For example, a study by Lera Boroditsky found that languages with different grammatical gender systems affect how speakers think about objects. Spanish and German speakers were asked to describe objects. They tended to describe objects in ways that matched the gender of the noun in their language. This suggests that a language's gender system can influence how people see objects.

How Research Has Changed

Researchers like Boroditsky and Levinson believe language influences thought in more limited ways. They study how thought, language, and culture connect. They use experiments to support their findings.

Behavior-Centered Research

Some studies use a "behavior-centered" approach. They compare how different language groups behave. Then, they look for reasons in the language system.

For example, Whorf linked fires at a chemical plant to workers using the word 'empty' for barrels with explosive fumes.

More recently, Everett studied the Pirahã language in Brazil. He found it lacked numbers and color terms in the usual way. He thought this showed how language affects thought. But universalists said this was because the Pirahã people didn't need those concepts.

Mandarin and Thai

Recent experiments looked at languages with different grammar. For example, some languages use "numeral classifiers" (like "a piece of paper"). Others don't. Research showed that language differences affect how humans categorize things. This influence can lessen over time if people learn another language.

Swedish and Spanish

A study found that language can affect how people guess time. Swedish speakers use distance terms like "long" or "short" for time. Spanish speakers use quantity terms like "a lot" or "little."

Researchers asked Swedish, Spanish, and bilingual speakers to guess how much time passed. They watched a line grow or a container fill. Swedish speakers were influenced by the line's length. Spanish speakers were influenced by the container's size. When bilinguals heard the Spanish word for duration, they focused on the container's fullness. When they heard the Swedish word, they focused on the line's length. This shows how language cues can change how we think about time.

Pronoun Use

Research by Kashima & Kashima found that people in countries where languages often drop pronouns (like Japanese) tend to be more "collectivistic." This means they focus more on the group. People who speak languages that don't drop pronouns (like English) tend to be more "individualistic." The researchers suggested that saying "you" and "I" clearly reminds speakers of the difference between themselves and others.

Future Tense

A 2013 study found that people who speak "futureless" languages (languages without a specific grammar for the future tense) save more money. They also retire with more wealth, smoke less, and are less overweight. This idea is called the "linguistic-savings hypothesis."

However, a study of Chinese (which can use "will" or not) found that people didn't act more impatiently when "will" was used. This suggests that culture or other factors might be at play, not just language.

Psycholinguistic Research

Psycholinguistic studies look at how language affects things like motion, emotion, and memory. The goal is to find differences in how people think that are *not* about language itself.

Recent work with bilingual speakers tries to separate the effects of language from the effects of culture. They look at how bilinguals perceive time, space, colors, and emotions differently from people who speak only one language.

One experiment found that speakers of languages with no numbers higher than two had trouble counting. For example, they made more mistakes telling the difference between six and seven taps. This might be because they couldn't use numbers to track the taps in their minds.

Other Areas of Influence

Linguistic relativity has made people wonder if we can change thoughts and emotions by changing language.

Science and Philosophy

This question touches on many big ideas. It asks if our minds are mostly born with us (innate) or if they are mostly learned from culture and society.

The "innate" view says humans share the same basic abilities. Differences due to culture are less important. It sees the mind as mostly biological. So, all humans with the same brain structure should think similarly.

Other ideas exist. The "constructivist" view says our thoughts are shaped by what we learn from society. The "relativist" view says different cultures use different ways of thinking. These ways might not always match up.

Another debate is whether thinking is a form of inner speech. Or if it happens before and separately from language.

In the philosophy of language, this question looks at how language, knowledge, and the world connect. Some philosophers think language directly represents the real world. Others argue that how we categorize things is subjective and chosen by us.

Therapy and Self-Development

Alfred Korzybski, a contemporary of Sapir and Whorf, developed "general semantics." This aimed to use language's influence on thinking to improve human minds. Korzybski believed that the structure of our usual language "enslaves" us. He thought it forces us to see the world in a certain way.

The general semantics movement influenced neuro-linguistic programming (NLP). This is a therapy technique that uses awareness of language to change thinking patterns.

Made-Up Languages

Authors like George Orwell explored how linguistic relativity could be used for political control. In Orwell's 1984, the government created a language called Newspeak. The goal was to make it impossible for people to think critically about the government. They reduced the number of words to limit people's thoughts.

Others have been fascinated by creating new languages. They hope these languages could lead to new, better ways of thinking.

- Loglan was designed to test the linguistic relativity idea. It aimed to make its speakers think more logically.

- Speakers of Lojban, an updated Loglan, say it helps them think logically.

- Suzette Haden Elgin created Láadan. She wanted to explore linguistic relativity by making a language that expressed a "female worldview." She felt European languages were "male-centered."

- John Quijada's Ithkuil was designed to push the limits of how many ideas a language could make speakers aware of at once.

- Sonja Lang's Toki Pona was created with a Taoist view. It explores how a simple language might guide human thought.

Computer Languages

Kenneth E. Iverson, who created the APL programming language, believed linguistic relativity applied to computer languages. He argued that powerful ways of writing code helped people think better about computer programs.

Paul Graham also explored this. He suggested a hierarchy of computer languages. More expressive languages were at the top. He described the "blub paradox." This says programmers are often happy with their language because it shapes how they think about programs.

Yukihiro Matsumoto, who created the programming language Ruby, was inspired by a science fiction novel based on the Sapir–Whorf Hypothesis.

Science Fiction Stories

Many science fiction stories have used the idea of linguistic relativity:

- In George Orwell's 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty Four, the government creates Newspeak. This language is designed so people cannot think rebellious thoughts.

- In Jack Vance's 1958 novel The Languages of Pao, special languages are used to create different classes in society. This helps the population resist invaders.

- Samuel R. Delany's 1966 novel Babel-17 features an advanced language that can be a weapon. Learning it changes how you see and think.

- Ted Chiang's 1998 short story "Story of Your Life" explores this idea with aliens. The 2016 film Arrival, based on this story, uses the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis as its main idea. The main character explains that "the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is the theory that the language you speak determines how you think."

- Gene Wolfe's novel The Book of the New Sun describes a people who speak a language made only of approved quotes.

Sociolinguistics and Linguistic Relativity

Sociolinguistics looks at how language varies in society. This includes how words are pronounced, chosen, and used in different situations. This suggests that sociolinguistics might also play a role in linguistic relativity.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hipótesis de Sapir-Whorf para niños

In Spanish: Hipótesis de Sapir-Whorf para niños

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |