Spanish conquest of the Maya facts for kids

The Spanish conquest of the Maya was a long fight during the Spanish takeover of the Americas. Spanish conquistadores (explorers and conquerors) and their helpers slowly took control of the lands belonging to the Maya people. This area is now part of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. The conquest started in the early 1500s and mostly ended in 1697.

Before the Spanish arrived, the Maya lands had many different kingdoms that often fought each other. Many conquistadors saw the Maya as people who needed to be forced to become Christians, even though the Maya had a very advanced civilization. The first time Europeans met the Maya was in 1502. This happened during Christopher Columbus's fourth trip, when his brother Bartholomew saw a Maya canoe. More Spanish trips followed in 1517 and 1519, landing on different parts of the Yucatán coast.

The Spanish conquest of the Maya took a very long time. The Maya kingdoms fought hard against becoming part of the Spanish Empire. It took almost 200 years to defeat them all. The Itza Maya and other groups in the lowlands of Petén Basin first met Hernán Cortés in 1525. But they stayed independent and unfriendly to the Spanish until 1697. That year, a big Spanish attack led by Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

The Maya lands were divided into many small kingdoms, which made it harder for the Spanish to conquer them quickly. But the Spanish used these divisions to their advantage. Spanish and Maya fighting styles and tools were very different. The Spanish tried to gather native people into new colonial towns called reducciones. The Spanish thought taking prisoners slowed down their victory, while the Maya wanted to capture live prisoners and valuable items. Maya warriors often used ambushes. To fight Spanish horses, the highland Maya dug pits with sharp wooden stakes. Native people who didn't want to live in the new towns often ran away into thick forests or joined other Maya groups that hadn't given up yet.

Spanish weapons included broadswords, rapiers, lances, pikes, halberds, crossbows, matchlocks, and light cannons. Maya warriors fought with spears tipped with flint, bows and arrows, stones, and wooden swords with sharp obsidian blades. They wore thick cotton armor for protection. The Maya did not have important things like the wheel, horses, iron, steel, or gunpowder. They also got very sick from diseases brought by the Europeans, against which they had no natural protection.

Contents

- Where the Maya Lived

- Maya Kingdoms Before the Spanish Arrived

- How the Conquest Started

- Weapons and Fighting Styles

- Impact of Old World Diseases

- First Meetings: 1502 and 1511

- Exploring the Yucatán Coast, 1517–1519

- Conquest of the Maya Highlands, 1524–1526

- Hernán Cortés in the Maya Lowlands, 1524–25

- Conquest and Settlement in Northern Yucatán, 1540–46

- Southern Lowlands, 1618–97

- Final Years of Conquest

- What the Conquest Left Behind

- Historical Records

- Images for kids

- See also

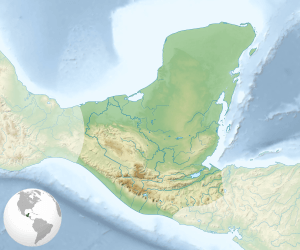

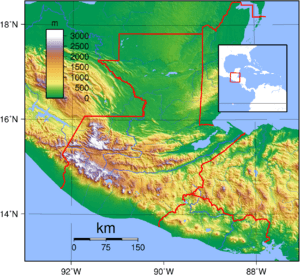

Where the Maya Lived

The Maya civilization lived in a large area. This included southeastern Mexico and northern Central America. It covered the whole Yucatán Peninsula, all of what is now Guatemala and Belize, and parts of western Honduras and El Salvador. In Mexico, the Maya lived in areas that are now the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Quintana Roo, and Yucatán.

The Yucatán Peninsula has the Caribbean Sea to the east and the Gulf of Mexico to the north and west. Most of it is a flat plain with few hills. The northern parts get less rain and have porous limestone, meaning less surface water. The northeastern part has forested swamps.

The Petén region is a flat, forested area with low ridges. It has small rivers and seasonal swamps. A chain of fourteen lakes runs across central Petén. The largest is Lake Petén Itza, which is about 32 by 5 kilometers (20 by 3 miles).

Chiapas is in the very southeast of Mexico. It has a Pacific coastline. Chiapas has two main highland areas: the Sierra Madre de Chiapas in the south and the Montañas Centrales (Central Highlands) in the middle. These are separated by a hot valley with moderate rainfall.

Maya Kingdoms Before the Spanish Arrived

The Maya were never one big empire. By the time the Spanish came, Maya civilization was thousands of years old. Many great cities had already risen and fallen.

Yucatán Peninsula Kingdoms

The first big Maya cities grew in the Petén Basin in the far south of the Yucatán Peninsula. This was around 600–350 BC. Petén was the heart of the ancient Maya civilization during its Classic period (around AD 250–900). By the early 10th century, many of the great cities in Petén were in ruins. However, many Maya still lived in Petén after the main cities were abandoned, especially near water sources.

In the early 1500s, the Yucatán Peninsula was still home to the Maya. It was split into many independent provinces. These provinces shared a common culture but had different ways of organizing their societies. When the Spanish found Yucatán, the provinces of Mani and Sotuta were two of the most important. They were enemies. The Xiu Maya of Mani became friends with the Spanish. The Cocom Maya of Sotuta became strong enemies of the European conquerors.

Other important groups in the northern Yucatán included Mani, Cehpech, and Chakan. To the east were Ah Kin Chel, Cupul, and Chikinchel. Along the Caribbean Sea were Ecab, Uaymil, and Chetumal. In the south, the Itza controlled much of Petén and parts of Belize. Their capital was Nojpetén, an island city on Lake Petén Itzá. The Kowoj were another important group, and they were enemies with the Itza.

Maya Highlands Kingdoms

The area that is now the Mexican state of Chiapas was divided between non-Maya Zoque and Maya people. In the Guatemalan Highlands, several powerful Maya states ruled. The Kʼicheʼ people had built a small empire covering much of the western Guatemalan Highlands. But in the late 1400s, the Kaqchikel rebelled against the Kʼicheʼ. They formed a new kingdom with Iximche as its capital. Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the west, and the Poqomam in the east.

How the Conquest Started

Christopher Columbus found the New World for Spain in 1492. After this, private adventurers made deals with the Spanish Crown. They would conquer new lands in exchange for taxes and the right to rule. In the first few decades, the Spanish settled the Caribbean and set up a main base in Cuba. By August 1521, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan had fallen to the Spanish. Within three years, the Spanish had conquered a large part of Mexico. This new land became New Spain, ruled by a viceroy who reported to the King of Spain.

Weapons and Fighting Styles

We came here to serve God and the King, and also to get rich.

The Spanish conquistadors were volunteers. Most did not get a regular salary. Instead, they received a share of the treasures, land, and native workers they captured. Many Spanish soldiers were already experienced from wars in Europe. The Maya lands being split into many small kingdoms made it harder for the Spanish to invade quickly. But the Spanish used these rivalries to their advantage.

The Spanish tried to gather native people into new colonial towns called reducciones. Native people often resisted by running away into hard-to-reach forests or joining other Maya groups that had not yet given up. Those who stayed in the reducciones often got sick from European diseases.

Spanish Weapons and Tactics

Spanish weapons and tactics were very different from those of the native people. The Spanish used crossbows, firearms (like muskets and cannons), war dogs, and war horses. The Maya had never seen horses before. Horses gave the mounted conquistador a huge advantage, allowing them to attack with more force and making them harder to hit.

Crossbows and early firearms were heavy and broke easily in the humid climate. The Maya did not have iron, steel, or functional wheels. Steel swords were a big advantage for the Spanish. The Spanish were so impressed by the Maya's padded cotton armor that they started using it instead of their own steel armor. The conquistadors also had better military organization and plans.

In Guatemala, the Spanish often used native allies. At first, these were Nahua people from Mexico. Later, they also included Maya. It's thought that for every Spanish soldier, there were at least 10 native helpers. Sometimes, there were as many as 30 native warriors for every Spaniard. These Mesoamerican allies were very important to the Spanish victories.

Native Weapons and Tactics

Maya armies were well-trained. Every healthy adult male could serve in the military. Maya states did not have standing armies. Warriors were called up by local leaders. There were also full-time mercenaries. Most warriors were farmers, so their crops usually came before war. Maya warfare focused on capturing prisoners and valuable items, not just destroying the enemy.

Maya warriors fought with spears tipped with flint, bows and arrows, and stones. They wore padded cotton armor soaked in salt water to make it tough. The Spanish said the Petén Maya used bows and arrows, fire-hardened poles, flint-headed spears, and two-handed wooden swords with sharp obsidian blades. Maya warriors carried wooden or animal hide shields decorated with feathers. The Maya often used ambushes and raids, which caused problems for the Spanish. To fight the Spanish cavalry, the highland Maya dug pits on roads, lined them with sharp stakes, and hid them with grass. This tactic killed many horses.

Impact of Old World Diseases

Diseases brought by the Spanish, like smallpox, measles, and influenza, had a huge effect on Maya populations. These diseases, along with typhus and yellow fever, were a major factor in the conquest. They killed many people even before battles began. It's estimated that 90% of the native population died from disease within the first 100 years of European contact.

A single soldier arriving in Mexico in 1520 carried smallpox. This started the terrible plagues that swept through the Americas. Modern estimates say that 75% to 90% of the native population died. Maya writings suggest that smallpox spread quickly through the Maya area the same year it reached central Mexico. These diseases caused 33–50% of the Maya highland population to die.

These diseases spread through Yucatán in the 1520s and 1530s, coming back many times throughout the 1500s. By the late 1500s, malaria arrived, and yellow fever was first reported in the mid-1600s. Death rates were high. About 50% of the people in some Yucatec Maya settlements died. The native population of the northeastern Yucatán was almost wiped out within 50 years of the conquest.

In Tabasco, the population of about 30,000 was reduced by about 90%. When Nojpetén fell in 1697, about 60,000 Maya lived around Lake Petén Itzá. It's estimated that 88% of them died in the first ten years of Spanish rule due to disease and war.

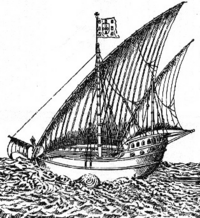

First Meetings: 1502 and 1511

On July 30, 1502, Christopher Columbus's brother, Bartholomew, met a large Maya trading canoe off the coast of Honduras. The canoe carried well-dressed Maya and valuable goods. The Europeans took some items and captured the elderly captain to be an interpreter. This was the first recorded meeting between Europeans and the Maya. News of these strangers likely spread along Maya trade routes.

In 1511, a Spanish ship called Santa María de la Barca sank off the coast of Jamaica. Twenty survivors, including Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, drifted to Yucatán. There, a Maya lord captured them. Captain Valdivia and four others were sacrificed. Aguilar and Guerrero were held as prisoners and slaves. Guerrero later became fully Mayanized and became a war leader.

Exploring the Yucatán Coast, 1517–1519

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, 1517

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba sailed from Cuba with a small fleet. They saw a Maya city inland from the Yucatán coast. Maya canoes came to meet them. The next day, the Spanish landed and were ambushed by Maya warriors. Thirteen Spaniards were injured by arrows. The Spanish fought back and found some low-grade gold items in temples, which excited them. They captured two Maya to use as interpreters. Two Spaniards later died from their arrow wounds.

The fleet continued along the coast. They were running out of fresh water. On February 23, 1517, they saw the Maya city of Campeche. They landed to get water. About fifty unarmed Maya approached them. The Spanish accepted an invitation to enter the city. Once inside, the Maya leaders made it clear the Spanish would be killed if they didn't leave. The Spanish retreated to their ships.

Ten days later, they found water near Champotón. Armed Maya warriors approached. By sunrise, the Spanish were surrounded by a large army. The Maya attacked, and all the Spanish were wounded, including Hernández de Córdoba. The Spanish lost over fifty men in an hour-long battle. Five more died later from their wounds. They were low on supplies, so they abandoned one ship. Hernández de Córdoba returned to Cuba and reported the discovery of gold. He died soon after from his wounds.

Juan de Grijalva, 1518

Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, was excited by the gold report. He sent a new expedition led by his nephew, Juan de Grijalva, in April 1518. They first landed on Cozumel island, where the Maya fled. The fleet sailed south, seeing three large Maya cities, but Grijalva did not land. They then sailed north around the peninsula and down the west coast. At Campeche, the Maya refused to trade water, so Grijalva fired cannons, and the inhabitants fled.

At Champotón, war canoes approached but were scared away by cannons. At the Tabasco River, Grijalva traded wine and beads for food. They received some gold trinkets and heard about the rich Aztec Empire to the west. The expedition continued far enough to confirm the Aztec Empire's existence. On their way back to Cuba, the Spanish attacked Champotón to get revenge for the previous year's defeat. One Spaniard was killed and fifty wounded, including Grijalva. Grijalva returned to Havana five months after leaving.

Hernán Cortés, 1519

Grijalva's return made people in Cuba very interested in Yucatán's riches. A new expedition of eleven ships and 500 men was organized, led by Hernán Cortés. His crew included famous conquistadors like Pedro de Alvarado.

The fleet first landed at Cozumel. Maya temples were torn down, and a Christian cross was put up. Cortés heard rumors of bearded men on the mainland. He rescued Gerónimo de Aguilar, who had been enslaved by a Maya lord. Aguilar had learned the Yucatec Maya language and became Cortés' interpreter.

From Cozumel, the fleet sailed around the Yucatán Peninsula to the Grijalva River. In Tabasco, Cortés anchored at Potonchán, a Chontal Maya town. The Maya prepared for battle, but Spanish horses and firearms quickly decided the outcome. The defeated Chontal Maya lords offered gold, food, clothing, and young women as tribute. One of these women was a young Maya noblewoman named Malintzin, who was given the Spanish name Marina. She spoke Maya and Nahuatl and helped Cortés talk with the Aztecs. From Tabasco, Cortés continued along the coast to conquer the Aztecs.

Conquest of the Maya Highlands, 1524–1526

Defeating the Kʼicheʼ, 1524

... we waited until they came close enough to shoot their arrows, and then we smashed into them; as they had never seen horses, they grew very fearful, and we made a good advance ... and many of them died.

Pedro de Alvarado and his army marched along the Pacific coast of Guatemala. This area was part of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom. A Kʼicheʼ army tried to stop the Spanish from crossing the Samalá River but failed. On February 8, 1524, Alvarado's army fought a battle at Xetulul (modern San Francisco Zapotitlán). The Spanish stormed the town. Alvarado then headed into the Sierra Madre mountains towards the Kʼicheʼ heartlands.

On February 12, 1524, Alvarado's Mexican allies were ambushed by Kʼicheʼ warriors but Spanish cavalry scattered them. The Spanish reached Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango) to find it empty. On February 18, 1524, a 30,000-strong Kʼicheʼ army fought the Spanish in the Quetzaltenango valley but was completely defeated. Many Kʼicheʼ nobles died. This battle weakened the Kʼicheʼ, and they asked for peace. They invited Pedro de Alvarado to their capital, Qʼumarkaj. Alvarado was suspicious but went to Qʼumarkaj with his army.

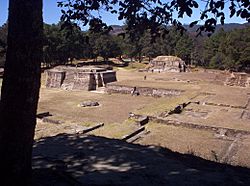

In March 1524, Pedro de Alvarado camped outside Qʼumarkaj. He invited the Kʼicheʼ lords, Oxib-Keh (the king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the king elect), to his camp. As soon as they arrived, he captured them. When the Kʼicheʼ attacked furiously, Alvarado had the captured lords burned to death. Then, he burned the entire city. After destroying Qʼumarkaj, Pedro de Alvarado asked the Kaqchikel of Iximche for an alliance against the remaining Kʼicheʼ. The Kaqchikel sent warriors to help. Many non-Kʼicheʼ people who were under Kʼicheʼ rule also surrendered to the Spanish.

Kaqchikel Alliance and Tzʼutujil Conquest, 1524

On April 14, 1524, the Spanish were welcomed into Iximche by the Kaqchikel lords. The Kaqchikel kings provided soldiers to help the Spanish against the Kʼicheʼ and the nearby Tzʼutujil kingdom. The Spanish stayed briefly before going to Atitlan. They returned to Iximche on July 23, 1524. On July 27, Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche the first capital of Guatemala, naming it Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala.

After two Kaqchikel messengers sent by Alvarado were killed by the Tzʼutujil, the Spanish and their Kaqchikel allies marched against the Tzʼutujil. Pedro de Alvarado led 60 cavalry, 150 Spanish infantry, and many Kaqchikel warriors. They reached the lake and fought the Tzʼutujil. The Spanish cavalry broke the Tzʼutujil force. The survivors fled to an island. The Spanish stormed the island, and the remaining Tzʼutujil swam to safety. This battle happened on April 18.

The next day, the Spanish entered Tecpan Atitlan, the Tzʼutujil capital, but it was empty. The Tzʼutujil leaders surrendered to Alvarado and swore loyalty to Spain. Alvarado considered them peaceful and returned to Iximche.

Kaqchikel Rebellion, 1524–1530

Pedro de Alvarado quickly started demanding gold from the Kaqchikels. This ruined their friendship. On August 28, 1524, the Kaqchikel people left their city and fled to the forests and hills. Ten days later, the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel.

The Kaqchikel began to fight the Spanish. They opened shafts and pits for the horses and put sharp stakes in them to kill them ... Many Spanish and their horses died in the horse traps. Many Kʼicheʼ and Tzʼutujil also died; in this way the Kaqchikel destroyed all these peoples.

The Spanish founded a new town nearby at Tecpán Guatemala. They abandoned it in 1527 because of constant Kaqchikel attacks. They moved their capital to Ciudad Vieja. The Kaqchikel resisted the Spanish for several years. But on May 9, 1530, tired from fighting, the two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilderness. They surrendered at the new Spanish capital. The people who used to live in Iximche were moved to other towns.

Siege of Zaculeu, 1525

At the time of the conquest, the main Mam population was in Xinabahul (modern Huehuetenango city). But Zaculeu's strong defenses made it a safe place during the conquest. Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras, Pedro de Alvarado's brother, attacked Zaculeu in 1525. He had 40 Spanish cavalry, 80 Spanish infantry, and about 2,000 Mexican and Kʼicheʼ allies. Gonzalo de Alvarado left Tecpán Guatemala in July 1525 and marched to Momostenango, which fell quickly after a four-hour battle.

The next day, Gonzalo de Alvarado marched on Huehuetenango. He was met by a Mam army of 5,000 warriors. The Mam army was defeated by a Spanish cavalry charge. The Mam leader, Canil Acab, was killed. The surviving warriors fled to the hills. The Spanish army rested, then continued to Huehuetenango, finding it empty.

Kaybʼil Bʼalam, the Mam leader, had heard about the Spanish and had moved to his fortress at Zaculeu with about 6,000 warriors. The fortress had strong defenses. Gonzalo de Alvarado attacked the weaker northern entrance. Mam warriors fought hard but were pushed back by repeated cavalry charges. Kaybʼil Bʼalam realized he couldn't win in an open battle, so he pulled his army back inside the walls. Alvarado began to besiege the fortress. An army of about 8,000 Mam warriors came from the mountains to help Zaculeu, but they were destroyed by the Spanish cavalry. After several months, the Mam were starving. Kaybʼil Bʼalam finally surrendered the city in mid-October 1525. The Spanish found 1,800 dead native people inside the city. After Zaculeu fell, a Spanish garrison was set up in Huehuetenango.

Hernán Cortés in the Maya Lowlands, 1524–25

In 1524, after conquering the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led an expedition to Honduras by land. He traveled through Acalan in southern Campeche and the Itza kingdom in northern Petén. His goal was to defeat Cristóbal de Olid, whom he had sent to conquer Honduras, but who had become independent. Cortés left Tenochtitlan on October 12, 1524, with 140 Spanish soldiers, 3,000 Mexican warriors, and supplies. He marched into Maya territory in Tabasco.

The expedition reached the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá on March 13, 1525. The priests with the expedition held a mass in front of the Itza king, Kan Ekʼ. Cortés accepted an invitation to visit Nojpetén. When he left, Cortés left behind a cross and a lame horse. The Itza treated the horse as a god, but it soon died.

From the lake, Cortés continued his difficult journey south. He lost most of his horses. The expedition got lost in the hills north of Lake Izabal and almost starved. They found a Maya boy who led them to safety. Cortés found a village on Lake Izabal and crossed the Dulce River to a settlement called Nito. He waited there for the rest of his army. By this time, only a few hundred men were left. Cortés found the Spaniards he was looking for, only to learn that Cristóbal de Olid's rebellion had already been put down. Cortés then returned to Mexico by sea.

Conquest and Settlement in Northern Yucatán, 1540–46

In 1540, Francisco de Montejo (the Elder), who was in his late 60s, gave his royal rights to colonize Yucatán to his son, Francisco Montejo the Younger. In early 1541, Montejo the Younger moved his forces to Campeche. There, with 300 to 400 Spanish soldiers, he set up the first permanent Spanish town council in the Yucatán Peninsula. Soon after, Montejo the Younger called the local Maya lords and ordered them to surrender to the Spanish Crown. Many lords surrendered peacefully, including the ruler of the Xiu Maya.

Montejo the Younger's cousin met the Canul Maya at Chakan. On January 6, 1542, he founded the second permanent town council, naming the new colonial town Mérida. On January 23, Tutul Xiu, the lord of Mani, came to the Spanish camp in Mérida peacefully. He was very impressed by a Catholic mass and converted to Christianity. Tutul Xiu was the ruler of the most powerful province in northern Yucatán. His surrender and conversion had a big impact and encouraged other western provinces to accept Spanish rule. The eastern provinces continued to resist.

Montejo the Younger then sent his cousin to Chauaca, where most eastern lords greeted him peacefully. The Cochua and Cupul Maya resisted but were quickly defeated. Montejo continued to the eastern Ekab province. When nine Spaniards drowned in a storm and another was killed by hostile Maya, rumors spread. Both the Cupul and Cochua provinces rebelled again. The Spanish hold on the eastern peninsula remained weak.

On November 8, 1546, an alliance of eastern provinces launched a coordinated uprising against the Spanish. The provinces of Cupul, Cochua, Sotuta, Tazes, Uaymil, Chetumal, and Chikinchel united to drive the invaders out. The uprising lasted four months. Eighteen Spaniards were surprised in eastern towns and were sacrificed. Over 400 allied Maya were killed. Mérida and Campeche were warned. Montejo the Younger and his cousin were in Campeche. Montejo the Elder arrived in Mérida from Chiapas in December 1546 with reinforcements. The rebellious eastern Maya were finally defeated in one battle, where twenty Spaniards and several hundred allied Maya were killed. This battle marked the final conquest of the northern Yucatán Peninsula. Many Maya from the eastern and southern areas fled to the still unconquered Petén Basin in the far south.

Southern Lowlands, 1618–97

The Petén Basin is now part of Guatemala. In colonial times, it was under the Governor of Yucatán, then later under Guatemala. The period of contact in the Petén lowlands lasted from 1525 to 1700. Spanish weapons and cavalry, which were very effective in northern Yucatán, were not as good for fighting in the thick forests of lowland Petén.

Early 1600s

After Cortés' visit in 1525, no Spanish tried to visit the warlike Itza of Nojpetén for almost 100 years. In 1618, two Franciscan friars from Mérida tried to peacefully convert the Itza in central Petén. They were welcomed by the Itza king, Kan Ekʼ. But their attempts to convert the Itza failed, and the friars left on friendly terms. They returned in 1619, and Kan Ekʼ welcomed them again. However, the Maya priesthood was hostile, and the missionaries were forced to leave.

In March 1622, Captain Francisco de Mirones Lezcano set out from Yucatán to attack the Itza. He was joined by Friar Diego Delgado. Delgado went ahead to Nojpetén with Christianized Maya and soldiers. Soon after arriving, the Itza captured and sacrificed the Spanish party. On January 27, 1624, an Itza war party led by AjKʼin Pʼol surprised Mirones and his soldiers in a church at Sakalum and killed them. Spanish reinforcements arrived too late. These events stopped all Spanish attempts to contact the Itza until 1695.

Late 1600s

In 1692, Martín de Ursúa y Arizmendi suggested building a road from Mérida south to connect with the Guatemalan colony. This was part of a bigger plan to conquer the independent native groups. In March 1695, Captain Alonso García de Paredes led 50 Spanish soldiers south into Kejache territory. They met armed Kejache resistance and retreated.

In March 1695, Captain Juan Díaz de Velasco set out from Cahabón in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, with 70 Spanish soldiers and many Maya archers. They reached Lake Petén Itzá and fought with Itza hunting parties. The Spanish met a large force of Itzas and retreated south.

In mid-May 1695, García again marched south from Campeche with 115 Spanish soldiers and 150 Maya musketeers. García ordered a fort built at Chuntuki, about 105 km (65 miles) north of Lake Petén Itzá. This served as the main military base for the "Royal Road" project.

Assault on Nojpetén

Martín de Urzúa y Arizmendi arrived on the western shore of Lake Petén Itzá on February 26, 1697. They built a heavily armed attack boat called a galeota, which carried 114 men and at least five cannons. On March 10, Ursúa met with Itza and Yalain leaders and invited Kan Ekʼ to his camp three days later. Kan Ekʼ did not arrive. Instead, Maya warriors gathered along the shore and in canoes. That morning, a water attack was launched on Kan Ek's capital. The city fell after a short but bloody battle. Many Itza warriors died, and the Spanish had few casualties. After the battle, the remaining defenders swam to the mainland and disappeared into the forests. The Spanish occupied the empty town. Martín de Ursúa renamed Nojpetén as Nuestra Señora de los Remedios y San Pablo, Laguna del Itza. Kan Ekʼ was soon captured with help from the Yalain Maya ruler. The Kowoj king was also captured, along with other Maya nobles. With the defeat of the Itza, the last independent native kingdom in the Americas fell to the Europeans.

Final Years of Conquest

During the campaign to conquer the Itza, the Spanish sent expeditions to move the Mopan north of Lake Izabal and the Chʼol Maya of the Amatique forests. They were resettled on the south shore of the lake. By the late 1700s, the local people were mostly Spaniards and people of mixed race. There was a big decrease in population around Lake Izabal due to constant slave raids by the Miskito Sambu from the Caribbean coast.

In the late 1600s, the small Chʼol Maya population in southern Petén and Belize was forced to move to Alta Verapaz. By 1699, the Toquegua people no longer existed as a separate group due to deaths and intermarriage. Around this time, the Spanish decided to bring the independent Mopan Maya north of Lake Izabal under control. Catholic priests from Yucatán founded several mission towns around Lake Petén Itzá in 1702–1703. Surviving Itza and Kowoj were resettled in these new towns. Kowoj and Itza leaders in these towns rebelled in 1704, but the rebellion was quickly crushed. Its leaders were executed, and most mission towns were abandoned. By 1708, only about 6,000 Maya remained in central Petén, compared to ten times that number in 1697. Disease caused most deaths, but Spanish expeditions and wars between native groups also played a part.

What the Conquest Left Behind

The initial shock of the Spanish conquest was followed by many years of harsh treatment of the native peoples, both allies and enemies. Over the next 200 years, Spanish rule slowly forced Spanish cultural ways onto the conquered people. The Spanish reducciones created new towns laid out in a grid pattern, like Spanish cities. They had a central plaza, a church, and a town hall for the local government, called the ayuntamiento. This type of settlement can still be seen today.

Bringing Catholicism was the main way culture changed. This led to a mix of old Maya beliefs and new Catholic ones. European tools and livestock were introduced, replacing older tools. Cattle, pigs, and chickens became common. New crops like sugarcane and coffee led to large farms that used native labor. Some native leaders, like the Xajil Kaqchikel noble family, managed to keep some status during the colonial period. In the late 1700s, adult native men were heavily taxed. They were often forced into debt peonage, where they had to work to pay off debts. Western Petén and nearby Chiapas remained sparsely populated, and the Maya there avoided contact with the Spanish.

Historical Records

The story of the Spanish conquest of Guatemala comes from many sources. The Spanish themselves wrote accounts. These include two letters by Pedro de Alvarado in 1524, describing his first campaign. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote a long account of the conquest of Mexico and nearby areas, called Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España ("True History of the Conquest of New Spain"). His story generally matches Alvarado's. He also wrote about Cortés' expedition and the conquest of the Chiapas highlands. Friar Bartolomé de las Casas wrote a very critical account of the Spanish conquest, including events in Guatemala.

The Tlaxcalan allies of the Spanish also wrote their own accounts. These included a letter to the Spanish king complaining about how they were treated after the war. Two pictorial accounts, painted in the native style, still exist: the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan and the Lienzo de Tlaxcala. Stories of the conquest from the Maya's point of view are found in native documents, like the Annals of the Kaqchikels. A letter from the defeated Tzʼutujil Maya nobles to the Spanish king in 1571 describes how the conquered people were exploited.

Colonial historian Francisco Antonio de Fuentes y Guzmán wrote La Recordación Florida in 1690. It is an important work on Guatemalan history. Field research has often supported his estimates of native population and army sizes.

In 1688, colonial historian Diego López de Cogolludo wrote about the Spanish missionary trips in 1618 and 1619. He based his work on a report by Fuensalida, which is now lost.

Franciscan friar Andrés Avendaño y Loyola wrote his own account of his trips to Nojpetén in the late 1600s. When the Spanish finally conquered Petén in 1697, they produced many documents. Juan de Villagutierre Soto-Mayor, a Spanish colonial official, wrote a detailed history of Petén from 1525 to 1699.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Conquista española de los territorios mayas para niños

In Spanish: Conquista española de los territorios mayas para niños

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |