Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Qʼumarkaj (Utatlán)

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.1225–1524 | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Capital | Qʼumarkaj | ||||||

| Common languages | Classical Kʼicheʼ | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Ajpop | |||||||

|

• ~1225–1250 (first)

|

Bʼalam Kitze | ||||||

|

• ~1500–1524 (last)

|

Oxib Keh | ||||||

| History | |||||||

|

• Established

|

c.1225 | ||||||

| 1524 | |||||||

|

|||||||

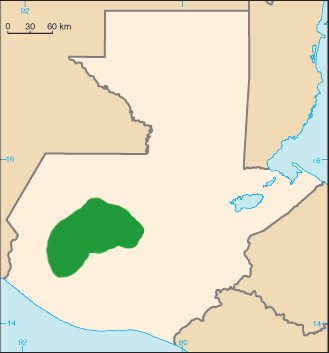

The Kʼicheʼ kingdom of Qʼumarkaj was a powerful state in the highlands of modern-day Guatemala. The Kʼicheʼ (Quiché) Maya founded it in the 13th century. It grew bigger throughout the 15th century. In 1524, Spanish and Nahua forces led by Pedro de Alvarado conquered it.

The Kʼicheʼ kingdom was strongest under King Kʼiqʼab. He ruled from the fortified city of Qʼumarkaj. This city is also known by its Nahuatl name, Utatlán. It was near the modern town of Santa Cruz del Quiché. During Kʼiqʼab's rule, the Kʼicheʼ controlled large parts of highland Guatemala, even reaching into Mexico. They also took control of other Maya peoples like the Tzʼutujil, Kaqchikel, and Mam. They also ruled over the Nahuan Pipil people.

Contents

How do we know about the Kʼicheʼ Kingdom?

The history of the Kʼicheʼ Kingdom comes from several old documents. These were written after the Spanish arrived. Some were in Spanish, and others were in native languages like Classical Kʼicheʼ and Kaqchikel.

Important Historical Books

One very important book is the Popol Vuh. It tells stories about myths and also lists the family history of the Kaweq ruling family. Another key document is the Annals of the Cakchiquels. This book shares the history of the Kaqchikel people, who were sometimes allies and sometimes enemies of the Kʼicheʼ.

Many other documents, called títulos, also tell parts of Kʼicheʼ history. Each título shares the story from the viewpoint of a specific Kʼicheʼ family group. We also learn from writings by Spanish conquerors and church leaders. Plus, there are official papers from the time when Spain ruled the area.

History of the Kʼicheʼ Kingdom

How did the Kʼicheʼ Kingdom begin?

The Mayan Kʼicheʼ people lived in the highlands of Guatemala since 600 BCE. But the recorded history of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom started around 1200 CE. At this time, people from the Mexican Gulf coast came into the highlands. These newcomers are called the "Kʼicheʼ forefathers" in old documents. They started the three main ruling families of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom.

These invaders were made up of seven tribes. Three were Kʼicheʼ families (the Nima Kʼicheʼ, Tamub, and Ilokʼab). The others were the ancestors of the Kaqchikel, Rabinal, and Tzʼutujil peoples. There was also a seventh tribe called the Tepew Yaqui.

We don't know much about where these invaders came from. Old records say they couldn't talk to the local Kʼicheʼ people when they arrived. They were called yaquies, which means they spoke Nahuatl. Some historians think they were traders from the Putún Maya. Others believe they were conquerors who spoke both Nahuatl and Chontal Maya. They were influenced by the Toltec culture. It's clear that the Kʼicheʼ language was influenced by Nahuan words around this time. The Kʼicheʼ forefathers brought their tribal gods with them. The main god of the Kʼicheʼ tribe was the sky god Tohil.

Founding the Kingdom (around 1225–1400)

| Ajpop of Qʼumarkaj | |

| (ruling periods estimated by generations) | |

| Bʼalam Kitze | ~1225–1250 |

| Kʼokʼoja | ~1250–1275 |

| E Tzʼikin | ~1275–1300 |

| Ajkan | ~1300–1325 |

| Kʼokaibʼ | ~1325–1350 |

| Kʼonache | ~1350–1375 |

| Kʼotuja | ~1375–1400 |

| Quqʼkumatz | ~1400–1435 |

| Kʼiqʼabʼ | ~1435–1475 |

| Vahxakʼ i-Kaam | ~1475–1500 |

| Oxib Keh | ~1500–1524 |

The "forefathers" took control of the local highland peoples. They built their first capital city at Jakawitz. This city was in the Chujuyup valley. During this time, the Kaqchikel, Rabinal, and Tzʼutujil tribes were allies of the Kʼicheʼ. They were under Kʼicheʼ rule. The languages of these four groups were very similar back then. But as they had less contact and later became enemies, their languages changed into the different ones we know today.

The Kʼicheʼ people themselves had three main family groups: the Nima Kʼicheʼ, the Tamubʼ, and the Ilokʼabʼ. Each group had a different role. The Nima Kʼicheʼ were the rulers. The Tamub were likely traders. The Ilokʼab were warriors. Each of these groups was further divided into smaller family lines, each with its own duties.

After taking over Jakawitz under Balam Kitze, the Kʼicheʼ, now led by Tzʼikin, expanded their land. They moved into Rabinal territory and took control of the Poqomam with help from the Kaqchikel. Then they went southwest and built Pismachi, a large religious center.

At Pismachi, Kʼoqaib and Kʼonache ruled. But soon, fights broke out between the family groups. The Ilokʼabs left Pismachi and settled in a nearby town called Mukwitz Chilokʼab. During the rule of Kʼotuja, the ahpop (the Kʼicheʼ ruler's title), the Ilokʼabs rebelled. But they were strongly defeated. Kʼotuja made the Kʼicheʼ more powerful. He also tightened his control over the Kaqchikel and Tzʼutujil peoples. He did this by having his family members marry into their ruling families.

Quqʼkumatz and Kʼiqʼab (around 1400–1475)

Under Kʼotuja's son, Quqʼkumatz, the Nima Kʼicheʼ family group also left Pismachi. They settled nearby at Qʼumarkaj, which means "place of the rotten cane." Quqʼkumatz became known as the greatest "Nagual" lord of the Kʼicheʼ. People believed he could magically change into snakes, eagles, jaguars, or even blood. He was said to be able to fly into the sky or visit the underworld, Xibalba.

Qʼuqʼumatz greatly expanded the Kʼicheʼ kingdom, first from Pismachiʼ and then from Qʼumarkaj. At this time, the Kʼicheʼ were close allies with the Kaqchikels. Qʼuqʼumatz sent his daughter to marry the lord of the Kʼoja. The Kʼoja were a Maya people living in the Cuchumatan mountains. But the Kʼoja king, Tekum Sikʼom, killed the bride instead of marrying her. This act started a war between the Kʼicheʼ-Kaqchikel alliance and the Kʼoja. Qʼuqʼumatz died in the battle against the Kʼoja.

After his father died, Kʼiqʼab, his son and heir, swore to get revenge. Two years later, he led the Kʼicheʼ-Kaqchikel alliance against his enemies. The Kʼicheʼ army entered Kʼoja at dawn. They killed Tekum Sikʼom and captured his son. Kʼiqʼab brought his father's bones back to Qʼumarkaj. He also took many prisoners and all the jade and metal the Kʼoja had. He conquered several towns in the Sacapulas area and the Mam people near Zaculeu.

During Kʼiqʼab's rule, the Kʼicheʼ kingdom grew even larger. It included Rabinal, Cobán, and Quetzaltenango. It stretched west to the Okos River, near the border between Mexico and Guatemala. With help from the Kaqchikel, the kingdom's eastern border reached the Motagua River. Its southern border reached Escuintla.

In 1470, a rebellion happened in Qʼumarkaj. It was during a big celebration with many important highland peoples present. Two of Kʼiqʼab's sons and some of his vassals rebelled against him. They killed many high-ranking lords, Kaqchikel warriors, and members of the Kaweq family. The rebels tried to kill Kʼiqʼab himself. But his loyal sons defended him in Pakaman, outside the city. Because of the rebellion, Kʼiqʼab had to give power to the rebelling Kʼicheʼ lords. These newly powerful Kʼicheʼ lords then turned against their Kaqchikel allies. The Kaqchikel were forced to leave Qʼumarkaj and build their own capital at Iximche.

After King Kʼiqʼab died in 1475, the Kʼicheʼ fought against both the Tzʼutujils and the Kaqchikels. They might have been trying to get back the power Qʼumarkaj once had.

Decline and Conquest by the Spanish

After Kʼiqʼab's death, the Kʼicheʼ kingdom became weaker. They constantly fought against the Kaqchikel, Tzʼutujil, Rabinal, and Pipil peoples. Under their leader Tepepul, the Kʼicheʼ tried a surprise attack on Iximché. The people there were weak from a famine. But the Kaqchikel learned about the attack and defeated the Kʼicheʼ army.

Constant wars continued until 1522, when the two peoples made a peace agreement. Even though the Kʼicheʼ had some military successes during this time, they never became as powerful as before. For example, they took control of the Rabinal and the people on the Pacific coast of Chiapas.

Around 1495, the Aztec empire, which was very strong in central Mexico, started to influence the Pacific coast and Guatemalan highlands. The Aztec ruler Ahuitzotl conquered the Soconusco province, which used to pay tribute to the Kʼicheʼ. Later, when Aztec traders came to Qʼumarkaj, the Kʼicheʼ ruler 7 Noj was so angry that he told them to leave his kingdom and never return.

However, in 1510, Aztec messengers from Moctezuma II arrived in Qʼumarkaj. They asked for tribute from the Kʼicheʼ. The Kʼicheʼ were forced to accept being under Aztec rule. From 1510 to 1521, Aztec influence in Qʼumarkaj grew. The Kʼicheʼ lord 7 Noj also married two daughters of the Aztec ruler. This made the Aztec rule even stronger. During this time, Qʼumarkaj also became known as Utatlán, which is the Nahuatl translation of its name. When the Spanish defeated the Aztecs in 1521, the Aztecs sent messages to the Kʼicheʼ ruler, telling him to get ready for battle.

Before the Spanish-led army arrived, diseases brought by Europeans hit the Kʼicheʼ. The Kaqchikels became allies with the Spanish in 1520, even before the Spanish reached Guatemala. They told the Spanish about their enemies, the Kʼicheʼ, and asked for help. Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado sent messengers to Qʼumarkaj. He asked them to peacefully accept Spanish rule and stop fighting the Kaqchikel. The Kʼicheʼ refused and prepared for war.

In 1524, Pedro de Alvarado arrived in Guatemala. He had 135 horsemen, 120 foot soldiers, and 400 Aztec, Tlaxcaltecs, and Cholultec allies. The Kaqchikels quickly promised to help them fight. The Kʼicheʼ knew all about the Spanish army's movements through their spies. When the army reached the Kʼicheʼ town of Xelajú Noj (Quetzaltenango), the town's leader sent word to Qʼumarkaj.

The Kʼicheʼ chose Tecún Umán, a lord from Totonicapán, to lead their army against the Spanish. He was ritually prepared for the battle. He and his 8,400 warriors met the Spanish/Aztec/Kaqchikel army outside Pinal, south of Quetzaltenango. The Kʼicheʼ were defeated. After several more defeats, the Kʼicheʼ offered to become subjects of the Spanish. They invited the Spanish to Qʼumarkaj.

However, Alvarado tricked the lords of Qʼumarkaj. He captured them and burned them alive. He then put two lower-ranking Kʼicheʼ leaders in charge as his puppet rulers. He continued to conquer other Kʼicheʼ communities in the area. Qʼumarkaj was destroyed and leveled. This was to stop the Kʼicheʼ from rebuilding their strong city. The community moved to the nearby town of Santa Cruz del Quiché.

How was Kʼicheʼ Society Organized?

In the Late Postclassic period, the Qʼumarkaj area had about 15,000 people. The people in Qʼumarkaj were divided into two main social groups: the nobility and their vassals.

Nobles and Vassals

The nobles were called the ajaw. The vassals were known as the al kʼajol. The nobles were direct descendants of the warlords who founded the kingdom. These warlords likely came from the Gulf coast around 1200 AD. Over time, they adopted the language of the people they ruled. The nobles were seen as sacred and wore special royal symbols. Their vassals served as foot soldiers. They had to follow the laws made by the nobles. However, vassals could earn military titles if they fought bravely in battle. These social divisions were very strict, like castes.

Merchants were a special class. They had privileges, but they had to pay tribute to the nobles. Besides these groups, there were also farmers and craftspeople. Slaves were also part of society. These included people who had committed crimes and prisoners of war.

Lineages and Rulers

There were twenty-four important family groups, or nimja, in Qʼumarkaj. nimja means "big house" in Kʼicheʼ. These groups were closely connected to the palaces where the nobles did their work. Their duties included arranging marriages, holding feasts, and giving ceremonial speeches.

These family groups were strongly patrilineal, meaning power and names passed down through the father's side. They were grouped into four larger, more powerful nimja that chose the city's rulers. When the Spanish arrived, the four ruling nimja were the Kaweq, the Nijaib, the Saqik, and the Ajaw Kʼicheʼ. The Kaweq and the Nijaib each had nine main family lines. The Ajaw Kʼicheʼ had four, and the Saqik had two. Besides choosing the king and king-elect, the ruling Kaweq family also had a line that produced the powerful priests of Qʼuqʼumatz. These priests might have managed the city.

See also

In Spanish: Reino quiché de Q'umarkaj para niños

In Spanish: Reino quiché de Q'umarkaj para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |