Spanish conquest of Guatemala facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Spanish conquest of Guatemala |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||||

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado led the initial efforts to conquer Guatemala. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Independent indigenous kingdoms and city-states, including those of the Chajoma, Chuj, Itza, Ixil, Kakchiquel, Kejache, Kʼicheʼ, Kowoj, Lakandon Chʼol, Mam, Manche Chʼol, Pipil, Poqomam, Qʼanjobʼal, Qʼeqchiʼ, Tzʼutujil, Xinca, and Yalain | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

The Spanish conquest of Guatemala was a long fight. It lasted from 1524 to 1697. During this time, Spanish explorers and soldiers slowly took control of the land that is now Guatemala. Before the Spanish arrived, this area was home to many different kingdoms. Most of these were Maya groups.

Many Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) thought the Maya needed to be forced to change their religion. They did not care about the amazing things the Maya civilization had already achieved. Europeans first met the Maya in the early 1500s. A Spanish ship crashed on the Yucatán Peninsula in 1511. More Spanish trips followed in 1517 and 1519. The Maya kingdoms fought hard against the Spanish Empire. It took almost 200 years for the Spanish to defeat them all.

Pedro de Alvarado came to Guatemala in early 1524. He arrived from Mexico, which the Spanish had just conquered. He led a group of Spanish soldiers and native allies. Most of his allies were from Tlaxcala and Cholula. Many places in Guatemala still have Nahuatl names because of these Mexican allies. They helped translate for the Spanish.

The Kaqchikel Maya first joined forces with the Spanish. But they soon rebelled because the Spanish demanded too much from them. They did not give up until 1530. Meanwhile, the Spanish defeated other major Maya kingdoms in the highlands. They used help from their Mexican allies and Maya groups they had already conquered.

Hernán Cortés first met the Itza Maya and other lowland groups in 1525. But these groups stayed independent and unfriendly to the Spanish for a long time. It was not until 1697 that a big Spanish attack, led by Martín de Ursúa, finally defeated the last independent Maya kingdom.

Spanish and native fighting styles were very different. The Spanish wanted to win completely. They saw taking prisoners as a problem. The Maya, however, wanted to capture live prisoners and valuable items. The native people of Guatemala did not have some important technologies. They lacked wheels, horses, iron, steel, and gunpowder. They also got sick very easily from diseases brought by the Europeans. These diseases were new to them, so they had no way to fight them off.

The Maya preferred quick attacks and ambushes. They used spears, arrows, and wooden swords with sharp obsidian blades. The Xinca people used poison on their arrows. To fight the Spanish cavalry (soldiers on horseback), the Maya dug pits. They lined these pits with sharp wooden stakes.

Contents

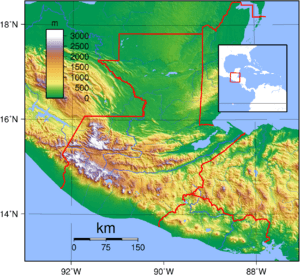

Guatemala Before the Spanish Arrived

In the early 1500s, the land that is now Guatemala was split into many different kingdoms. These kingdoms were always fighting each other. The most powerful groups were the Kʼicheʼ, the Kaqchikel, the Tzʼutujil, the Chajoma, the Mam, the Poqomam, and the Pipil. All of these were Maya groups, except for the Pipil. The Pipil were a Nahua group, like the Aztecs. They had small city-states along the Pacific coast. The Xinca were another non-Maya group in the southeastern coastal area. The Maya had never been one big empire. But by the time the Spanish came, their civilization was thousands of years old. Many great Maya cities had already risen and fallen.

Before the Spanish invasion, the Guatemalan Highlands were controlled by several strong Maya states. For centuries, the Kʼicheʼ had built a small empire. It covered much of the western highlands and the Pacific coast. But in the late 1400s, the Kaqchikel rebelled against the Kʼicheʼ. They started a new kingdom to the southeast with Iximche as its capital. Before the Spanish arrived, the Kaqchikel kingdom was slowly taking over the Kʼicheʼ kingdom. Other highland groups included the Tzʼutujil around Lake Atitlán, the Mam in the west, and the Poqomam in the east.

The Itza kingdom was the strongest in the Petén lowlands of northern Guatemala. Its capital was Nojpetén, on an island in Lake Petén Itzá. The second most important group was their enemy, the Kowoj. The Kowoj lived east of the Itza, around lakes like Salpetén and Yaxhá.

Native Weapons and Tactics

Maya warfare was not mainly about destroying the enemy. It was more about capturing people and valuable items. The Spanish described the weapons of the Petén Maya. These included bows and arrows, sharpened poles, flint-headed spears, and two-handed wooden swords. These swords had sharp obsidian blades, similar to the Aztec macuahuitl. Pedro de Alvarado wrote that the Xinca attacked the Spanish with spears, stakes, and poisoned arrows.

Maya warriors wore armor made of quilted cotton. This cotton was soaked in salt water to make it tough. This armor was as good as the steel armor worn by the Spanish. The Maya often used ambushes and quick raids. This made it hard for the Europeans to fight them. When the Spanish used cavalry, the highland Maya dug pits in the roads. They lined these pits with sharp, fire-hardened stakes. They covered the pits with grass and weeds. The Annals of the Kaqchikels say this tactic killed many horses.

The Spanish Conquerors

We came here to serve God and the King, and also to get rich.

The conquistadors were all volunteers. Most of them did not get a regular salary. Instead, they received a share of what they won. This included precious metals, land, and native workers. Many Spanish soldiers were already experienced from fighting in Europe.

Pedro de Alvarado led the first invasion of Guatemala. He was given the military title of Adelantado in 1527. He reported to the Spanish king through Hernán Cortés in Mexico. Other early conquistadors included Pedro de Alvarado's brothers and cousins. Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote a long story about the conquest. He was with Cortés when he crossed the northern lowlands. He also joined Pedro de Alvarado in the highlands. The invasion force also included dozens of armed African slaves and freedmen.

Spanish Weapons and Tactics

Spanish weapons and fighting methods were very different from those of the native people. The Spanish used crossbows, firearms (like muskets and cannons), war dogs, and war horses. For Mesoamerican people, capturing prisoners was important. But for the Spanish, taking prisoners slowed down their victory.

The people of Guatemala, even with their advanced civilization, did not have some key technologies. They did not use iron or steel. They also did not have functional wheels. Steel swords were perhaps the biggest advantage the Spanish had. Cavalry (soldiers on horseback) also helped them defeat native armies. The Spanish were so impressed by the Maya's quilted cotton armor that they started using it instead of their own steel armor. The conquistadors also had better military organization and plans. This allowed them to use their troops and supplies in ways that gave them a greater advantage.

In Guatemala, the Spanish always used native allies. At first, these were Nahua people from Mexico. Later, they also included Mayas. It is thought that for every Spanish soldier, there were at least 10 native allies. Sometimes, there were as many as 30 native warriors for every Spaniard. These Mesoamerican allies were very important in the conquest.

The Spanish also tried to gather native populations into new colonial towns. These were called reducciones. Native people often resisted this by running away to hard-to-reach places like mountains and forests.

Impact of Old World Diseases

The Spanish accidentally brought diseases like smallpox, measles, and influenza. These diseases, along with typhus and yellow fever, had a huge effect on Maya populations. These "Old World" diseases were new to the native people. They had no natural protection against them. This was a major reason for the Spanish victory. The diseases weakened armies and killed many people even before battles began.

These diseases were terrible for the Americas. It is thought that 90% of the native population died from disease within the first 100 years of European contact.

Before the Spanish arrived in Guatemala, several epidemics swept through the southern part of the country in 1519 and 1520. While the Spanish were fighting the Aztecs, a terrible plague hit the Kaqchikel capital of Iximche. The Kʼicheʼ capital, Qʼumarkaj, might also have suffered. It was likely a mix of smallpox and a lung disease. Experts believe that 33-50% of the highland population died. The population levels in the Guatemalan Highlands did not return to their old numbers until the mid-1900s.

When Nojpetén fell in 1697, about 60,000 Mayas lived around Lake Petén Itzá. Many were refugees from other areas. It is believed that 88% of them died in the first ten years of Spanish rule. This was due to disease and war.

Timeline of the Conquest

| Date | Event | Modern department (or Mexican state) |

|---|---|---|

| 1521 | Conquest of Tenochtitlan | Mexico |

| 1522 | Spanish allies scout Soconusco and receive delegations from the Kʼicheʼ and Kaqchikel | Chiapas, Mexico |

| 1523 | Pedro de Alvarado arrives in Soconusco | Chiapas, Mexico |

| February – March 1524 | Spanish defeat the Kʼicheʼ | Retalhuleu, Suchitepéquez, Quetzaltenango, Totonicapán and El Quiché |

| 8 February 1524 | Battle of Zapotitlán, Spanish victory over the Kʼicheʼ | Suchitepéquez |

| 12 February 1524 | First battle of Quetzaltenango results in the death of the Kʼicheʼ lord Tecun Uman | Quetzaltenango |

| 18 February 1524 | Second battle of Quetzaltenango | Quetzaltenango |

| March 1524 | Spanish under Pedro de Alvarado raze Qʼumarkaj, capital of the Kʼicheʼ | El Quiché |

| 14 April 1524 | Spanish enter Iximche and ally themselves with the Kaqchikel | Chimaltenango |

| 18 April 1524 | Spanish defeat the Tzʼutujil in battle on the shores of Lake Atitlán | Sololá |

| 9 May 1524 | Pedro de Alvarado defeats the Pipil of Panacal or Panacaltepeque near Izcuintepeque | Escuintla |

| 26 May 1524 | Pedro de Alvarado defeats the Xinca of Atiquipaque | Santa Rosa |

| 27 July 1524 | Iximche declared first colonial capital of Guatemala | Chimaltenango |

| 28 August 1524 | Kaqchikel abandon Iximche and break alliance | Chimaltenango |

| 7 September 1524 | Spanish declare war on the Kaqchikel | Chimaltenango |

| 1525 | The Poqomam capital falls to Pedro de Alvarado | Guatemala |

| 13 March 1525 | Hernán Cortés arrives at Lake Petén Itzá | Petén |

| October 1525 | Zaculeu, capital of the Mam, surrenders to Gonzalo de Alvarado y Contreras after a lengthy siege | Huehuetenango |

| 1526 | Chajoma rebel against the Spanish | Guatemala |

| 1526 | Acasaguastlán given in encomienda to Diego Salvatierra | El Progreso |

| 1526 | Spanish captains sent by Alvarado conquer Chiquimula | Chiquimula |

| 9 February 1526 | Spanish deserters burn Iximche | Chimaltenango |

| 1527 | Spanish abandon their capital at Tecpán Guatemala | Chimaltenango |

| 1529 | San Mateo Ixtatán given in encomienda to Gonzalo de Ovalle | Huehuetenango |

| September 1529 | Spanish routed at Uspantán | El Quiché |

| April 1530 | Rebellion in Chiquimula put down | Chiquimula |

| 9 May 1530 | Kaqchikel surrender to the Spanish | Sacatepéquez |

| December 1530 | Ixil and Uspantek surrender to the Spanish | El Quiché |

| April 1533 | Juan de León y Cardona founds San Marcos and San Pedro Sacatepéquez | San Marcos |

| 1543 | Foundation of Cobán | Alta Verapaz |

| 1549 | First reductions of the Chuj and Qʼanjobʼal | Huehuetenango |

| 1551 | Corregimiento of San Cristóbal Acasaguastlán established | El Progreso, Zacapa and Baja Verapaz |

| 1555 | Lowland Maya kill Domingo de Vico | Alta Verapaz |

| 1560 | Reduction of Topiltepeque and Lakandon Chʼol | Alta Verapaz |

| 1618 | Franciscan missionaries arrive at Nojpetén, capital of the Itzá | Petén |

| 1619 | Further missionary expeditions to Nojpetén | Petén |

| 1684 | Reduction of San Mateo Ixtatán and Santa Eulalia | Huehuetenango |

| 29 January 1686 | Melchor Rodríguez Mazariegos leaves Huehuetenango, leading an expedition against the Lacandón | Huehuetenango |

| 1695 | Franciscan friar Andrés de Avendaño attempts to convert the Itzá | Petén |

| 28 February 1695 | Spanish expeditions leave simultaneously from Cobán, San Mateo Ixtatán and Ocosingo against the Lacandón | Alta Verapaz, Huehuetenango and Chiapas |

| 1696 | Andrés de Avendaño forced to flee Nojpetén | Petén |

| 13 March 1697 | Nojpetén falls to the Spanish after a fierce battle | Petén |

Conquering the Highlands

Conquering the highlands was hard. There were many independent groups, not just one big enemy like in central Mexico. After the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, fell in 1521, the Kaqchikel Maya of Iximche sent messengers to Hernán Cortés. They said they would be loyal to the new ruler of Mexico. The Kʼicheʼ Maya of Qʼumarkaj might have sent a group too.

In 1522, Cortés sent Mexican allies to scout the Soconusco region. There, they met new groups from Iximche and Qʼumarkaj. Both powerful Maya kingdoms said they were loyal to the king of Spain. But Cortés's allies soon told him that the Kʼicheʼ and Kaqchikel were not truly loyal. They were bothering Spain's allies in the area.

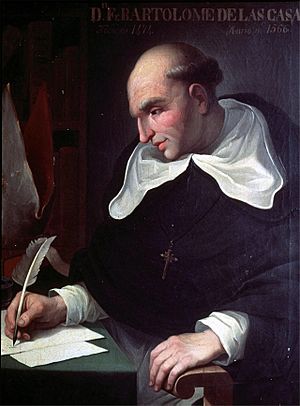

Cortés decided to send Pedro de Alvarado. Alvarado had 180 cavalry (horse soldiers), 300 infantry (foot soldiers), crossbows, muskets, and 4 cannons. He also had thousands of allied Mexican warriors. They arrived in Soconusco in 1523. Pedro de Alvarado was known for a massacre of Aztec nobles in Tenochtitlan. According to Bartolomé de las Casas, he did more terrible things during the conquest of the Maya.

Some groups stayed loyal to the Spanish after being conquered. These included the Tzʼutujil and the Kʼicheʼ of Quetzaltenango. They gave warriors to help with more conquests. But other groups soon rebelled. By 1526, many rebellions had started in the highlands.

Defeating the Kʼicheʼ Kingdom

... we waited until they came close enough to shoot their arrows, and then we smashed into them; as they had never seen horses, they grew very fearful, and we made a good advance ... and many of them died.

Pedro de Alvarado and his army moved along the Pacific coast without trouble. They reached the Samalá River in western Guatemala. This area was part of the Kʼicheʼ kingdom. A Kʼicheʼ army tried to stop the Spanish from crossing the river but failed. After crossing, the Spanish looted nearby towns. They wanted to scare the Kʼicheʼ.

On February 8, 1524, Alvarado's army fought at Xetulul. His Mexican allies called it Zapotitlán. The Kʼicheʼ archers hurt many Spanish soldiers. But the Spanish and their allies stormed the town. They set up camp in the marketplace. Alvarado then went up into the Sierra Madre mountains. He headed towards the Kʼicheʼ heartland. He crossed a pass into the fertile valley of Quetzaltenango.

On February 12, 1524, Kʼicheʼ warriors ambushed Alvarado's Mexican allies. They pushed them back. But the Spanish cavalry charge that followed shocked the Kʼicheʼ. They had never seen horses before. The cavalry scattered the Kʼicheʼ. The army then reached the city of Xelaju (modern Quetzaltenango). It was empty.

Many believe the Kʼicheʼ prince Tecun Uman died in a later battle. But Spanish records say at least one Kʼicheʼ lord died near Quetzaltenango. The death of Tecun Uman is said to have happened in the battle of El Pinar. Local stories say he died on the Plains of Urbina. This is near the village of Cantel. Pedro de Alvarado wrote about the death of one of the four lords of Qʼumarkaj. This was in his letter to Hernán Cortés on April 11, 1524.

Almost a week later, on February 18, 1524, a Kʼicheʼ army fought the Spanish. This happened in the Quetzaltenango valley. The Kʼicheʼ were completely defeated. Many Kʼicheʼ nobles died. So many Kʼicheʼ died that Olintepeque was called Xequiquel. This means "bathed in blood." In the early 1600s, the Kʼicheʼ king's grandson said the Kʼicheʼ army had 30,000 warriors. Modern experts think this is true. This battle greatly weakened the Kʼicheʼ army.

They asked for peace and offered gifts. They invited Pedro de Alvarado into their capital, Qʼumarkaj. Alvarado was very suspicious of the Kʼicheʼ. But he accepted and marched to Qʼumarkaj with his army.

The day after the battle of Olintepeque, the Spanish army arrived at Tzakahá. It surrendered peacefully. Spanish priests held a Catholic mass there. This site was chosen for the first church in Guatemala. It was named Concepción La Conquistadora. Tzakahá was renamed San Luis Salcajá. The first Easter mass in Guatemala was held there. High-ranking natives were baptized.

In March 1524, Pedro de Alvarado entered Qʼumarkaj. The Kʼicheʼ lords invited him after their big defeat. Alvarado feared a trap. He camped outside the city. He worried his cavalry could not move in the narrow streets of Qʼumarkaj. He invited the city's main lords, Oxib-Keh (the king) and Beleheb-Tzy (the king elect), to his camp. As soon as they arrived, he captured them.

The Kʼicheʼ warriors saw their lords taken. They attacked the Spanish allies. They killed one Spanish soldier. Alvarado then decided to burn the captured Kʼicheʼ lords to death. He then burned the entire city. After destroying Qʼumarkaj and killing its rulers, Pedro de Alvarado sent messages to Iximche. This was the capital of the Kaqchikel. He suggested an alliance against the remaining Kʼicheʼ. Alvarado wrote that they sent 4,000 warriors to help him. But the Kaqchikel recorded that they sent only 400.

Kaqchikel Alliance and Rebellion

On April 14, 1524, the Spanish were invited into Iximche. The lords Belehe Qat and Cahi Imox welcomed them. The Kaqchikel kings gave native soldiers. These soldiers helped the Spanish fight the Kʼicheʼ. They also helped defeat the nearby Tzʼutuhil kingdom.

The Spanish stayed only a short time in Iximche. They then continued through Atitlán, Escuintla, and Cuscatlán. The Spanish returned to the Kaqchikel capital on July 23, 1524. On July 27, Pedro de Alvarado declared Iximche the first capital of Guatemala. He named it Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala. The Spanish called Iximche "Guatemala." This came from the Nahuatl word Quauhtemallan, meaning "forested land."

Pedro de Alvarado quickly started demanding gold from the Kaqchikels. This ruined the friendship. He demanded 1000 gold leaves, each worth 15 pesos.

A Kaqchikel priest said their gods would destroy the Spanish. So, the Kaqchikel people left their city. They fled to the forests and hills on August 28, 1524. Ten days later, the Spanish declared war on the Kaqchikel. Two years later, on February 9, 1526, Spanish deserters burned the palace. They also robbed the temples and kidnapped a priest. The Kaqchikel blamed Pedro de Alvarado for these acts.

The Kaqchikel began to fight the Spanish. They opened shafts and pits for the horses and put sharp stakes in them to kill them ... Many Spanish and their horses died in the horse traps. Many Kʼicheʼ and Tzʼutujil also died; in this way the Kaqchikel destroyed all these peoples.

The Spanish built a new town nearby called Tecpán Guatemala. Tecpán means "palace" in Nahuatl. So, the new town's name meant "the palace among the trees." The Spanish left Tecpán in 1527. This was because of constant Kaqchikel attacks. They moved to the Almolonga Valley to the east. They rebuilt their capital there. This site is now the San Miguel Escobar district of Ciudad Vieja.

The Kaqchikel fought the Spanish for several years. But on May 9, 1530, they were tired of fighting. Their best warriors had died. Their crops had been abandoned. The two kings of the most important clans returned from the wilderness. A day later, many nobles and their families joined them. They surrendered at the new Spanish capital in Ciudad Vieja. The people who used to live in Iximche were spread out. Some moved to Tecpán, others to Sololá and towns around Lake Atitlán.

Siege of Zaculeu

Before the Spanish came, the Mam and the Kʼicheʼ were enemies. But when the Spanish arrived, things changed. Pedro de Alvarado said the Mam king Kaybʼil Bʼalam was welcomed in Qʼumarkaj. The Kʼicheʼ had failed to stop the Spanish there. The Mam king, Kaybʼil Bʼalam, suggested trapping the Spanish in the city. The Kʼicheʼ kings were then killed, which was seen as unfair. The Spanish quickly decided to march on the Mam.

At the time of the conquest, most Mam lived in Xinabahul (now Huehuetenango). But Zaculeu was a strong fortress. So, it was used as a safe place during the conquest. Gonzalo de Alvarado attacked Zaculeu in 1525. He was Pedro de Alvarado's brother. He had 40 Spanish cavalry, 80 Spanish infantry, and about 2,000 Mexican and Kʼicheʼ allies.

Gonzalo de Alvarado left the Spanish camp in July 1525. He marched to Totonicapán, using it as a supply base. From there, he went north to Momostenango. Heavy rains slowed him down. Momostenango fell quickly after a four-hour battle. The next day, Gonzalo de Alvarado marched on Huehuetenango. He met a Mam army of 5,000 warriors. They were from nearby Malacatán. The Mam army advanced in battle formation. But a Spanish cavalry charge broke their lines. The infantry finished off the Mam who survived. Gonzalo de Alvarado killed the Mam leader, Canil Acab, with his spear. The Mam army's resistance broke. The remaining warriors fled to the hills. Alvarado entered Malacatán without a fight. Only the sick and elderly were there. Messengers from the leaders offered to surrender. Alvarado accepted. The Spanish army rested for a few days. Then they continued to Huehuetenango. It was deserted. Kaybʼil Bʼalam had heard about the Spanish. He had moved to his fortress at Zaculeu. Alvarado sent a message to Zaculeu. He offered peace terms to the Mam king. The king did not reply.

Zaculeu was defended by Kaybʼil Bʼalam. He commanded about 6,000 warriors. They came from Huehuetenango, Zaculeu, Cuilco, and Ixtahuacán. The fortress was surrounded on three sides by deep ravines. It had strong walls and ditches. Gonzalo de Alvarado was outnumbered two to one. But he decided to attack the weaker northern entrance. Mam warriors held the northern approaches at first. But they fell back from repeated cavalry charges. About 2,000 more Mam warriors from inside Zaculeu reinforced the defense. But they could not push the Spanish back.

Kaybʼil Bʼalam saw that winning on an open battlefield was impossible. He pulled his army back inside the walls. Alvarado began a siege. An army of about 8,000 Mam warriors came from the Cuchumatanes mountains. They were from towns allied with Zaculeu. Alvarado left Antonio de Salazar to manage the siege. He marched north to fight the Mam army. The Mam army was disorganized. It was no match for the Spanish cavalry. The relief army was destroyed. Alvarado returned to the siege.

After several months, the Mam were starving. Kaybʼil Bʼalam finally surrendered the city in mid-October 1525. When the Spanish entered, they found 1,800 dead natives. The survivors were eating the bodies of the dead. After Zaculeu fell, a Spanish garrison was placed in Huehuetenango. Gonzalo de Alvarado returned to Tecpán Guatemala. He reported his victory to his brother.

Conquest of the Poqomam

In 1525, Pedro de Alvarado sent a small group to conquer Mixco Viejo. This was the capital of the Poqomam. When the Spanish approached, the people stayed inside their fortified city. The Spanish tried to attack from the west. They went through a narrow pass. But they were forced back with many losses. Alvarado himself led a second attack. He had 200 Tlaxcalan allies. But he was also pushed back.

The Poqomam then got more fighters, possibly from Chinautla. The two armies fought on open ground outside the city. The battle was messy and lasted most of the day. But the Spanish cavalry finally won. The Poqomam reinforcements had to retreat. Their leaders surrendered three days later. They told the Spanish about a secret entrance. It was a cave leading from a nearby river. This allowed people to go in and out of the city.

Alvarado used this information. He sent 40 men to block the cave exit. He launched another attack along the ravine from the west. Soldiers went in single file because it was so narrow. Crossbowmen and musketeers took turns. Each had a companion to shield them from arrows and stones. This tactic let the Spanish break through the pass. They stormed the city entrance. The Poqomam warriors fell back in confusion. They retreated through the city. The Spanish and their allies hunted them down. Those who escaped into the valley were ambushed by Spanish cavalry. These cavalry had been placed to block the cave exit. The survivors were captured and brought back to the city. The siege lasted over a month. Because the city was so strong, Alvarado ordered it burned. He moved the people to the new colonial village of Mixco.

Pacific Lowlands: Pipil and Xinca

Before the Spanish arrived, the western Pacific plain was controlled by the Kʼicheʼ and Kaqchikel states. The eastern part was home to the Pipil and the Xinca. The Pipil lived in the area of modern Escuintla and part of Jutiapa. The main Xinca land was east of the Pipil, in what is now Santa Rosa. There were also Xinca in Jutiapa.

For 50 years before the Spanish came, the Kaqchikel often fought the Pipil of Izcuintepeque (modern Escuintla). By March 1524, the Kʼicheʼ were defeated. The Spanish then allied with the Kaqchikel in April. On May 8, 1524, Pedro de Alvarado continued south. He had just arrived in Iximche and conquered the Tzʼutujil. He went to the Pacific coastal plain with about 6,000 soldiers. On May 9, he defeated the Pipil of Panacal near Izcuintepeque.

Alvarado said the land near the town was very hard to cross. It had thick plants and swamps. This made it impossible to use cavalry. So, he sent men with crossbows ahead. The Pipil pulled back their scouts because of heavy rain. They thought the Spanish would not reach the town that day. But Pedro de Alvarado pushed on. When the Spanish entered the town, the defenders were not ready. The Pipil warriors were inside, hiding from the rain.

In the battle, the Spanish and their allies had few losses. But the Pipil escaped into the forest. The weather and plants protected them from Spanish pursuit. Pedro de Alvarado ordered the town burned. He sent messengers to the Pipil lords. He demanded their surrender. Otherwise, he would destroy their lands. According to Alvarado's letter, the Pipil returned and submitted to him. They accepted the king of Spain as their ruler. The Spanish army camped in the captured town for eight days. A few years later, in 1529, Pedro de Alvarado was accused of being too brutal. This included his conquest of Izcuintepeque.

In Guazacapán, Pedro de Alvarado met people who were neither Maya nor Pipil. They spoke a different language. These were probably Xinca. Alvarado's force had 250 Spanish infantry. They were joined by 6,000 native allies, mostly Kaqchikel. Alvarado and his army defeated the most important Xinca city, Atiquipaque. It is thought to be in the Taxisco area. Alvarado said the Xinca warriors fought fiercely. They used spears, stakes, and poisoned arrows. The battle was on May 26, 1524. It greatly reduced the Xinca population.

Alvarado's army continued east from Atiquipaque. They captured several more Xinca cities. Tacuilula pretended to be peaceful. But they tried to fight the Spanish within an hour of their arrival. Taxisco and Nancintla fell soon after. Alvarado and his allies could not understand the Xinca language. So, Alvarado took extra care on the march east. He put ten cavalry at the front and back of his army.

Despite this, a Xinca army ambushed the baggage train. This happened soon after leaving Taxisco. Many native allies were killed. Most of the baggage was lost. This included all the crossbows and horse ironwork. This was a serious problem. Alvarado camped his army in Nancintla for eight days. He sent two groups to fight the attacking army. Jorge de Alvarado led the first attempt. He had thirty to forty cavalry. They defeated the enemy. But they could not get back any lost baggage. Much of it had been destroyed by the Xinca for trophies. Pedro de Portocarrero led the second attempt. He had a large group of foot soldiers. But he could not fight the enemy because the land was too difficult. So, he returned to Nancintla. Alvarado sent Xinca messengers to contact the enemy. But they did not return.

Messengers from Pazaco offered peace. But when Alvarado arrived the next day, the people were ready for war. Alvarado's troops met many warriors. They quickly defeated them through the city streets. From Pazaco, Alvarado crossed the Río Paz. He then entered what is now El Salvador.

After conquering the Pacific plain, the people paid taxes to the Spanish. They paid with valuable goods like cacao, cotton, salt, and vanilla. Cacao was especially important.

Northern Lowlands

The time of contact in Guatemala's northern Petén lowlands lasted from 1525 to 1700. Spanish weapons and cavalry were strong in the northern Yucatán. But they were not good for fighting in the thick forests of lowland Guatemala.

Cortés in Petén

In 1525, after conquering the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés led a trip to Honduras by land. He crossed the Itza kingdom in northern Petén, Guatemala. His goal was to defeat Cristóbal de Olid. Cortés had sent Olid to conquer Honduras. But Olid had become independent.

Cortés had 140 Spanish soldiers, 93 of them on horseback. He also had 3,000 Mexican warriors, 150 horses, pigs, artillery, and supplies. He also brought 600 Chontal Maya carriers. They reached the north shore of Lake Petén Itzá on March 13, 1525.

Cortés accepted an invitation from Kan Ekʼ, the Itza king. He visited Nojpetén (Tayasal). He crossed to the Maya city with 20 Spanish soldiers. The rest of his army went around the lake to meet him. When he left Nojpetén, Cortés left behind a cross and a lame horse. The Spanish did not officially contact the Itza again until 1618. That's when Franciscan priests arrived. They said Cortés's cross was still standing at Nojpetén.

From the lake, Cortés went south. He followed the western slopes of the Maya Mountains. This was a very hard journey. It took 12 days to cover 32 kilometers. He lost more than two-thirds of his horses. He came to a river swollen by heavy rains. Cortés turned upstream to the Gracias a Dios rapids. It took two days to cross and he lost more horses.

On April 15, 1525, the group reached the Maya village of Tenciz. With local guides, they went into the hills north of Lake Izabal. Their guides left them there. The group got lost and almost starved. Then they captured a Maya boy who led them to safety. Cortés found a village on Lake Izabal, perhaps Xocolo. He crossed the Dulce River to Nito. This was somewhere on the Amatique Bay. He waited there for his army to gather. By this time, only a few hundred people were left. Cortés found the Spaniards he was looking for. He learned that Olid's own officers had already stopped his rebellion. Cortés built a simple boat. With canoes, he went up the Dulce River to Lake Izabal. He had about 40 Spaniards and some native people. He first thought he had reached the Pacific Ocean. But he soon realized his mistake. At the west end of the lake, he marched inland. He fought the Maya natives at Chacujal. He took a lot of food from the city. He sent supplies back to Nito in his boat. He built rafts to carry supplies downriver. He returned to Nito with them. Most of his men marched back by land. Cortés then returned to Mexico by sea.

Land of War: Verapaz

By 1537, the area north of the new colony of Guatemala was called the Tierra de Guerra ("Land of War"). But it was also known as Verapaz ("True Peace"). The Land of War was a place being conquered. It was a dense forest, hard for the Spanish army to enter. When the Spanish found a town, they moved its people. They put them in a new colonial settlement near the jungle's edge. This made it easier for the Spanish to control them. This plan slowly emptied the forest. It also made it a safe place for people escaping Spanish rule. This included individuals and whole communities.

The Land of War, from the 1500s to the early 1700s, was a huge area. It stretched from Sacapulas in the west to Nito on the Caribbean coast. It went north from Rabinal and Salamá. It was between the highlands and the northern lowlands. It includes parts of modern Baja Verapaz, Alta Verapaz, Izabal, Petén, and El Quiché. The western part of this area belonged to the Qʼeqchiʼ Maya.

Pedro Orozco, a Mam leader, helped the Dominicans. They wanted to peacefully convert the people of Verapaz. On May 1, 1543, King Charles V rewarded the Mam. He promised they would never be given in encomienda.

Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas came to Guatemala in 1537. He immediately argued against military conquest. He wanted peaceful missionary work instead. Las Casas offered to conquer the Land of War by preaching the Catholic faith. The Dominicans promoted the name Verapaz instead of Land of War. The governor of Guatemala, Alonso de Maldonado, agreed. He promised not to create new encomiendas if Las Casas succeeded.

Las Casas and other Dominican friars settled in Rabinal, Sacapulas, and Cobán. They converted several native chiefs. They taught Christian songs to native Christian merchants. These merchants then went into the area.

one could make a whole book ... out of the atrocities, barbarities, murders, clearances, ravages and other foul injustices perpetrated ... by those that went to Guatemala

This way, they gathered Christian natives in what is now Rabinal. Las Casas helped create the New Laws in 1542. These laws were made by the Spanish king. They aimed to control the bad actions of conquistadors and colonists. They protected the native people. Because of this, the Dominicans faced strong resistance from Spanish colonists. The colonists felt their interests were threatened. This distracted the Dominicans from their peaceful efforts.

In 1543, the new colonial town of Santo Domingo de Cobán was founded. It was for the relocated Qʼeqchiʼ people. Santo Tomás Apóstol was founded nearby that same year. In 1560, it was used to resettle Chʼol communities. In 1555, the Acala Chʼol killed the Spanish friar Domingo de Vico. De Vico had upset a local ruler by scolding him for having many wives. The native leader shot the friar with an arrow. In response, a punishment group was sent. It was led by Juan Matalbatz, a Qʼeqchiʼ leader. The independent natives they captured were taken to Cobán. They were resettled in Santo Tomás Apóstol.

Lake Izabal and the Lower Motagua River

Gil González Dávila left Hispaniola in early 1524. He wanted to explore the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. He sailed to the north coast of Honduras. After founding Puerto de Caballos, Gil Gónzalez sailed west. He went along the coast to the Amatique Bay. He founded a Spanish settlement near the Dulce River in Guatemala. He named it San Gil de Buena Vista. He started a conquest in the mountains between Honduras and Guatemala.

González left some men at San Gil de Buena Vista. They were led by Francisco Riquelme. González sailed back east to Honduras. The colonists at San Gil did not do well. They soon looked for a better place. They moved to the important native town of Nito. This was near the mouth of the Dulce River. They were in a bad state and almost starving. They were still there when Hernán Cortés passed through on his way to Honduras. They joined his group.

[[File:Castillo de San Felipe de Lara in Guatemala 06.jpg|thumb|right|The Castillo de San Felipe was a Spanish fort that guarded the entrance to Lake Izabal.|alt=A large stone fort with several towers and walls, situated on a body of water. There are trees on the land around the fort. The sky is blue with some clouds.}} The Dominicans settled in Xocolo on Lake Izabal in the mid-1500s. Xocolo became known for its inhabitants practicing witchcraft. By 1574, it was the most important stop for European trips inland. It stayed important until 1630. But it was abandoned in 1631.

In 1598, Alfonso Criado de Castilla became governor of Guatemala. The port of Puerto de Caballos was in bad shape. It was often attacked by pirates. So, he sent someone to check out Lake Izabal. After getting permission from the king, Criado de Castilla ordered a new port built. It was named Santo Tomás de Castilla. It was in a good spot on the Amatique Bay, near the lake. Then, work began on a highway. It went from the port to the new capital, modern Antigua Guatemala. It followed the Motagua Valley into the highlands. Native guides would not go further downriver than Quiriguá. This was because the area was home to the unfriendly Toquegua people.

In April 1604, the leaders of Xocolo and Amatique convinced 190 Toquegua to settle on the Amatique coast. They used the threat of Spanish force. The new settlement quickly lost people. Some sources say the Amatique Toquegua were gone before 1613. But Mercedarian friars were still helping them in 1625. In 1628, the Manche Chʼol towns were put under the governor of Verapaz. Francisco Morán was their church leader. Morán wanted a stronger approach to converting the Manche. He moved Spanish soldiers into the area. This was to protect against raids from the Itza to the north. The new Spanish soldiers in an area that had not seen many Spanish before made the Manche rebel. They then left their settlements. By 1699, the Toquegua no longer existed as a separate group. This was due to many deaths and marrying with Amatique Indians. Around this time, the Spanish decided to move the independent Mopan Maya. They lived north of Lake Izabal. The north shore of the lake was fertile but mostly empty. So, the Spanish planned to move the Mopan from the forests. They wanted them in an area where they could be more easily controlled.

During the fight to conquer the Itza of Petén, the Spanish sent groups. They bothered and moved the Mopan north of Lake Izabal. They also moved the Chʼol Maya from the Amatique forests to the east. They were resettled in colonial towns. These were San Antonio de las Bodegas and San Pedro de Amatique. By the late 1700s, the native people in these towns were gone. The local people were now only Spaniards, mulattos, and mixed-race people. They were all connected to the Castillo de San Felipe de Lara fort. This fort guarded the entrance to Lake Izabal. The main reason for the huge population loss around Lake Izabal was slave raids. These raids were by the Miskito Sambu from the Caribbean coast. They effectively ended the Maya population there. The captured Maya were sold into slavery. This was a common practice among the Miskito.

Conquering Petén

From 1527 onwards, the Spanish were more active in the Yucatán Peninsula. They set up several colonies and towns by 1544. The Spanish impact on the northern Maya was huge. It included invasion, diseases, and selling up to 50,000 Maya as slaves. This caused many Maya to flee south. They joined the Itza around Lake Petén Itzá in Guatemala. The Spanish knew the Itza Maya were a center of resistance. So, they tried to surround their kingdom. They cut off their trade routes for almost 200 years. The Itza fought back by getting their neighbors to ally with them.

Dominican missionaries worked in Verapaz and southern Petén. This was from the late 1500s through the 1600s. They tried peaceful conversion, but with limited success. In the 1600s, the Franciscans believed they could not make the Maya peaceful or Christian. Not as long as the Itza held out at Lake Petén Itzá. Many people escaped Spanish-held lands to find safety with the Itza. This was a problem for the Spanish.

Fray Bartolomé de Fuensalida visited Nojpetén in 1618 and 1619. Franciscan missionaries tried to use their own ideas about the kʼatun prophecies. They wanted to convince the Itza king, Kan Ekʼ, and his priests. They said it was time for conversion. But the Itza priests understood the prophecies differently. The missionaries were lucky to escape alive.

In 1695, the Spanish decided to connect Guatemala with Yucatán. Guatemalan soldiers conquered some Chʼol communities. The most important was Sakbʼajlan. It was renamed Nuestra Señora de Dolores. Franciscan friar Andrés de Avendaño tried again to conquer the Itza in 1695. He convinced the Itza king that the Kʼatun 8 Ajaw was the right time. This Maya calendar cycle began in 1696 or 1697. He said it was time for the Itza to become Christian and accept the king of Spain. However, the Itza had local Maya enemies who resisted this. In 1696, Avendaño was lucky to escape with his life. The Itza's continued resistance was embarrassing for the Spanish. So, soldiers were sent from Campeche to take Nojpetén once and for all.

Fall of Nojpetén

Martín de Ursúa arrived at Lake Petén Itzá on February 26, 1697. He built a galeota, a large, armed boat. The Itza capital fell in a bloody attack on March 13, 1697. The Spanish attack caused many deaths on the island. Many Itza Maya who tried to swim across the lake were killed. After the battle, the remaining defenders disappeared into the forests. The Spanish occupied an empty Maya town.

The Itza and Kowoj kings were soon captured. Other Maya nobles and their families were also taken. With Nojpetén safely in Spanish hands, Ursúa returned to Campeche. He left a small group of soldiers on the island. They were isolated among the hostile Itza and Kowoj. These groups still controlled the mainland.

The soldiers were joined in 1699 by a military group from Guatemala. Mixed-race ladino civilians came with them. They wanted to start their own town around the military camp. The settlers brought diseases. These killed many soldiers and colonists. They also swept through the native population. The Guatemalans stayed only three months. Then they returned to Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala. They took the captured Itza king with them. His son and two cousins also went. The cousins died on the long journey. Ajaw Kan Ekʼ and his son spent their lives under house arrest in the capital.

Final Years of Conquest

In the late 1600s, the small Chʼol Maya population in southern Petén and Belize was forced to move. They went to Alta Verapaz. There, they joined the Qʼeqchiʼ population. The Chʼol of the Lacandon Jungle were resettled in Huehuetenango in the early 1700s.

Catholic priests from Yucatán founded several mission towns. These were around Lake Petén Itzá in 1702–1703. Surviving Itza and Kowoj were moved to these new towns. This was done by a mix of convincing and force. Kowoj and Itza leaders in these towns rebelled in 1704. The rebellion was well-planned. But it was quickly crushed. Its leaders were killed. Most of the mission towns were abandoned. By 1708, only about 6,000 Maya remained in central Petén. This was compared to ten times that number in 1697. Disease caused most deaths. But Spanish trips and fighting between native groups also played a part.

Legacy of the Spanish Conquest

The first shock of the Spanish conquest was followed by many years of harsh treatment. This affected native people, both allies and enemies. Over the next 200 years, Spanish rule slowly forced Spanish culture on the conquered people. The Spanish reducciones created new towns. These were laid out in a grid pattern, like Spanish cities. They had a central plaza, a church, and a town hall. This style of settlement can still be seen today. The local government was run by the Spanish or their descendants. Or it was closely controlled by them.

Bringing Catholicism was the main way culture changed. This led to a mix of religions. Old World cultural things were adopted by Maya groups. For example, the marimba, a musical instrument from Africa, became popular. The biggest change was the end of the old economic system. European technology and animals replaced it. Iron and steel tools replaced older tools. Cattle, pigs, and chickens largely replaced hunting for food. New crops were also brought in. However, sugarcane and coffee led to plantations. These plantations used native labor unfairly.

About 60% of Guatemala's modern population is Maya. They live mostly in the central and western highlands. The eastern part of the country saw many Spanish people move there. This led to more Spanish culture. Guatemalan society is divided by a class system. It is largely based on race. Maya farmers and craftspeople are at the bottom. Mixed-race ladino workers and government officials form the middle and lower class. Above them are the criollo elite. These are people of pure European family. Some native leaders, like the Xajil, kept some status. They were a well-known Kaqchikel noble family. They wrote down the history of their region.

See also

In Spanish: Conquista de Guatemala para niños

In Spanish: Conquista de Guatemala para niños

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |